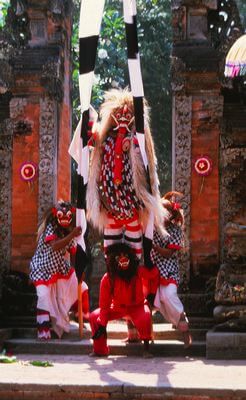

Barong, Rangda, and Calonarang

- Barong is the village protector; two men are dancing under its heavy body and manipulate its head Robert Wihtol

Two mythical beings are ever-present in Bali. They can be seen in travel advertisements and postcards, and their colourful masks are sold everywhere as souvenirs. They are Barong, resembling a lion with its long mane, and the witch Rangda with matted hair and large tusks.

- Rangda, the evil witch, is the embodiment of black magic Robert Wihtol

Both are invested with a strong aura of magic. Old, authentic Barong and Rangda masks with holy inscriptions, consecrated in temple rituals, are kept in village temples, where they are revered as patron spirits. The mythology of Barong and Rangda is complex and anything but unequivocal. They often have leading roles in village events and drama performances, of which the best known is the Calonarang, based on an East Javanese legend.

Barong, The Protector of the Village

The term barong can refer to a mythological animal mask in general. In practice, however, it usually means Barong, a mythical animal figure known to all Balinese. Inside its hairy body are two male dancers, whose movements and steps must be completely co-ordinated to perform its fast turns and leaps. The forward dancer supports and moves the head and jaws.

The decorative, slightly Chinese-influenced Barong mask is stylistically related to the old wayang wong masks. The Barong mask has bulging eyes, large ears, and a headdress of gilt leather and shining pieces of mirror, and large ears. Similarly, the upright tall and the ornaments of the hairy body, made of the same material, glimmer along with the Barong’s movements.

The Barong figure is believed to have its roots in the ancient Chinese lion dance, which is still performed at New Year celebrations everywhere in the Chinese world. The lion dance was also previously common on many islands in Indonesia. Later, the Balinese lion figure acquired its own features, and became a creature combining various elements in a way typical only of Bali.

Barong is not actually a lion, but a composite of various animals. The Barong types are named according to the dominating animal figure: Barong Asu combines the features of a dog and a lion, while Barong Machan resembles a tiger, the Barong Lembu has the shape of a cow, and the Barong Bankali has the features of a wild boar.

Grossly simplified, Barong is usually described as a manifestation of virtue. It is, however, too capricious and unpredictable to be interpreted unequivocally as such. Nevertheless, Barong is revered as the protector of villages, and its outfit and mask are regarded as sacred. During festivities, the Barong figure is carried around the village to the accompaniment of music. Each banjar or village council has at least one Barong mask and outfit of its own.

The Barong figures are given human and identifiable traits. The history of many Barongs is known, particularly those regarded as exceptionally magical, and their reputation has spread throughout the island. On some occasions Barong is taken to a neighbouring village to meet his lover, and grand gatherings of many Barongs occasionally take place. In practice, the Barong processions, games, and gatherings are also a way for young men and women from neighbouring villages to become acquainted with one other.

Along with the various types of processions, specific forms of drama have evolved around Barong. Possibly the oldest of these is the hereditary Barong Kedingkling, a form of sacred dance-drama developed in the eighteenth century to ward off an epidemic. In this drama Barong appears together with monkey characters borrowed from the Ramayana.

- A friendly monkey is helping Barong Robert Wihtol

The performance lasts all day, beginning in the village temple and dispersing later throughout the village. The monkeys accompanying Barong are permitted various forms of mischief, such as pilfering food and well-meant teasing. Many villages have their own versions of this tradition. Barong is also a central figure in the Calonarang drama, and modern, non-ritual Barong dramas have been developed mainly for tourist shows.

Rangda, The Queen of Black Magic

- Dramatic arrival of Rangda Robert Wihtol

Rangda is the other main mythological figure of the Balinese. Its symbolic significance is also complex and hard to interpret. It is often regarded as the incarnation of “evil”, but in fact the mask of this ferocious witch is revered in the village temples as a patron and a protector against evil.

The mask has a horrifying appearance with its aggressive bulging eyes, long tusks, and red tongue extending down to the waist. Rangda is related to the Durga goddess of India, a ferocious emanation of the spouse of Shiva, the creator and destroyer, a kind of personification of holy wrath. Rangda is basically a manifestation of rage and destruction, and in performances many deities and supernatural beings often suddenly appear in the frightening shape of Rangda when experiencing such extreme moods.

Rangda, however, completely lacks the jocularity and good nature of Barong. She is dangerous and destructive, possessing the power of making her opponents fall into a trance. The actor of the Rangda character may often fall into a trance himself while performing. The magical powers and destructiveness of Rangda place many requirements on the performer, who is often a respected individual in his community.

Rangda’s movements deliberately contradict all the ideals of Balinese classical dance. She often stands simply with her legs apart, trembling spasmodically, extending her hands, and shaking her long fingernails in readiness to attack her enemies. Like Barong, Rangda appears at village festivities, but she may also participate in large gatherings of Barongs and Rangdas as well as in many kinds of rituals and dramas.

Calonarang, The Battle between Good and Evil

The Calonarang is probably one of the best-known forms of drama, in which Barong and Rangda play central roles. It is an ancient East Javanese text in the Kawi language, and was originally influenced by Indian tantric teachings. It tells of a Javanese princess who controlled her spouse, a weak Balinese king, by means of black magic. In Bali the text was first converted into drama form in the 1890s, and it soon established its position as a central form of drama.

According to Balinese custom, this new dance-drama employed existing histrionic conventions. The various scenes of the original Calonarang drama are performed in the village temple and in various parts of the village, at road crossings, and in the cemetery. The two latter sites, like the seashore, are regarded by the Balinese as the most unholy and magically dangerous places in their environment.

For the Balinese, black magic – the central theme of the Calonarang drama – is living reality, and some communities on the island still practise it. The Calonarang is a form of theatre laden with magical meaning, and was originally meant to ward off an epidemic. The plot is constructed as follows.

Calonarang, the widow of Girah (played by a male priest in trance), a practitioner of black magic possessing two very powerful books, is furious because no one dares to marry her daughter. To avenge this wrong, the widow intends to destroy the kingdom with an epidemic brought about by black magic.

She directs her pupils in a magic ritual. Young maidens with flowing hair and white costumes perform a strange dance, a kind of negative version of Balinese classical dance. News of the widow’s intentions has spread throughout the island, and the king decides to send his prime minister to fight the widow. The king instructs his minister, who then goes on with his retinue to meet the witch.

The magical rite directed by the widow is approaching its climax when the prime minister arrives at the scene. The widow now appears in the shape of the furious Rangda, refusing to bow to the minister’s demands. A battle is inevitable. Rangda falls into a trance and incites everyone to attack her.

- Under Rangda’s spell the villagers start to stab themselves with their kris daggers Robert Wihtol

The performance often reaches its culmination in the famous self-stabbing dance, where the villagers, incited to a blind rage, attack Rangda, who casts a spell over them with her white magic scarf. Finally, the villagers begin to stab themselves with their wavy-bladed kris daggers, as Rangda has the power to make people turn against themselves. This kris dance or onying was originally an independent form of trance ritual, but at present it is almost always performed at the end of a Calonarang or Barong performance. The village priests control the proceedings, moving the exhausted participants to the most sacred courtyard of the temple where they are revived with incense and holy water and brought back to consciousness.

- Barong comes to rescue the kris dancers Robert Wihtol

Calonarang includes long comic scenes, where clowns, speaking in the vernacular, comment on the proceedings, entertaining the audience with their obscene humour. The Akademi Seni Tari Indonesia has created a shortened version of the Calonarang, from which the ritual elements have been excluded.

The energetic and flamboyant characters of Barong and Rangda have particularly appealed to Western audiences. In the 1940s hotels began to stage shortened Barong and Rangda spectacles, which were the predecessors of the present tourist shows.