Early Periods

The Sukhothai Period (1240–1438)

According to the traditional rendering of Thai or Siamese history, the first independent Tai Kingdom was Sukhothai (1240–1438). During this period the Tais created their own art style, which was eclectic at the beginning, combining elements from the Mons, Khmers, and the Srivijaya maritime empire in the south, and from Sri Lanka, from where they adopted, through the Mon, the core of their culture, Theravada Buddhism. (read more about Tai, Thai and Siamese).

In fact, several Tai principalities and kingdoms evolved; parallel to this evolution, Lanna in the north was the one most closely connected with Sukhothai, which had served as a Khmer outpost in the 12th century. Through dynastic connections and intermarriage with the older ruling Mon and Khmer elite, the Tai of Sukhothai gained political power and independence, which ended when it became a vassal of another Tai kingdom, Auytthaya, in 1350. Sukhothai was finally incorporated into it in 1438.

The supposedly earliest literary evidence of Thai culture and history in general, is the c. 1293 AD stone inscription attributed in the 19th century to King Ramkhamkhaen, the third sovereign of Sukhothai and architect of its power. The authenticity of the inscription is, however, now questioned. Whether the document is authentic or not does not concern us, since the information given by it, as far as theatre and dance are concerned, mainly contains different terms for musical instruments and forms of merrymaking.

A more important text for theatre and dance research, and originally a Sukhothai period text, is the famous Indian-influenced Theravada Buddhist cosmology The Three Worlds or Traiphum. It is attributed to the 14th century King Lithai of Sukhothai and it gives a detailed description of the 31 levels of the Theravada Buddhist cosmos. It mentions dance in several connections. It has deeply influenced the temple architecture, imagery and dance of the region.

Early Dance Images

Besides the few textual sources mentioned above, there exist early dance images, in this case temple reliefs, which give us some information about dance during the early phases of the history of Thailand. They clearly show that many of the elements of dance reflected Indian influence while, at the same time, many features also show that the Indian influence had already been adapted to the local tastes and needs. Thus they give extremely important information about how the present movement techniques have gradually evolved.

- Dancing kinnari or a human dancer performing a kinnari dance, Mon Period stucco relief, 8th–11th centuries, Bangkok National Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

One of the earliest of them is a Mon-period fragment of an 8th to 11th century stucco half-human half-bird mythical kinnari, which once formed a part of the decoration on a temple wall south of Sukhothai. It shows a winged female figure with prominent, crown-like headgear. Her body is bent in the exaggerated tribhanga position of Indian dance. Her right arm is thrown across the upper body and the left arm is uplifted and bent from the elbow.

- Training of the backward-bent finger movements in Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

When one is familiar with the hand and finger movements of many Thai folk and classical dances, one can easily recognise similarities between them and the kinnari figure. Thai dances often emphasise the extremely elastic finger movements in which the fingers are excessively stretched backwards, an aesthetical and technical speciality with its own training methods. Thus the kinnari’s upper hand could also be seen repeating this kind of movement. If this interpretation is correct, the kinnari figure, while echoing Indian and Sri Lankan traditions, also represents localisation of these traditions with its over-bent elbow and backwards-stretched fingers, both features typical of dances of this region still today.

- Dancer in a stucco-covered gate tower of Wat Phra Rattana Mahathat in Chaliang. The temple was founded in the 13th century, but the relief is probably later Jukka O. Miettinen

In the main entrance of a large temple compound, near Sukhothai, there are reliefs depicting dynamic dancers. They are shown in an Indian-influenced leg position with bent knees and with one raised foot. The arms are stretched wide open. Indigenous features, however, can also be recognised, as their over-bent elbow joints are clearly visible and their fingers are strongly bent backwards.

- Terracotta relief showing a dancer, formerly part of the iconographical programme of Wat Chang Rop in Kamphaeng Phet, 16th–17th centuries, Kamphaeng Phet National Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

One of the few dance images from the region of Sukhothai is a terracotta relief showing a dancing woman. It is dated to the 16th–17th centuries, i.e. to the period when Ayutthaya was the dominant centre of the Thai hegemony. There is no doubt that the pose of this female dancer is related to Indian-derived dance technique. The bent knees and the uplifted heels create an impression of dynamic footwork that is characteristic of many Indian dance traditions even today. The hands in front of the torso seem to portray an Indian-influenced mudra-like gesture. However, it is very likely that the image is not merely an iconographical loan from Indian tradition, since similar poses, with slight variations, can also be found in Khmer dance imagery, although executed in a different style. These reliefs could imply that a dance tradition incorporating this kind of poses could have spread to a larger area, covering the Khmer territory as well as the Central Plains of Thailand.

The Ayutthaya Period (1351–1767)

Sukhothai is traditionally regarded as the cradle of Tai culture. What was to become the Thai or Siamese culture of the Bangkok or Rattanakosin period was, however, formulated in the kingdom of Ayutthaya during its rule of over four centuries from 1351 to 1767.

Ayutthaya annexed Sukhothai, displaced the Khmer dominions in the regions of present-day Thailand and even conquered the Khmer capital of Angkor for the first time in 1352 and later in 1431 and subjected the Khmers to vassalage. During the Ayutthaya period the Khmer influence was adapted to form an important part of Thai heritage in all fields of culture. Warring with its neighbours, Malays, the Khmer and the kingdoms of Lanna and Burma, Ayutthaya further expanded its territories.

Ayutthaya’s population was ethnically diverse. The eclectic belief system combined animistic beliefs, different forms of Buddhism dominated by Theravada, and Chinese elements, as well as Brahman practices and the concept of the god-king adapted, to a great extent, from the Khmer.

Auytthaya’s concept of a “god-king”, which naturally had political ends to bolster and mystify the kingship in an increasingly complicated political system, amalgamated several ideologies. It combined the Hindu-Brahman concept of devaraja or god-king with that of chakravatin or a descendant of God Shiva, and a further Buddhist flavour was given with the ideology of dharmaraja or righteous ruler, which associated the king with a bodhisattva or a Buddha-to-be.

Ayutthaya’s military power, her exports of rice and her role as an important trade centre with active contacts with China, Japan and the Southern Silk Road made Ayutthaya a wealthy and powerful empire in the 15th century, when King Trailok (1448–1488) established his administrative reforms. They gave shape to Siamese society and its administration, which was to remain more or less unchanged until the mid-19th century.

In 1758 Ayutthaya was attacked by its archenemies, the Burmese, who finally sacked the city in 1767 and destroyed nearly all its palaces, temples and libraries, taking tens of thousands of prisoners of war with them back to Burma. Among the captives were also dancers and other artists, who gave new impetus to Burmese culture just like the Khmer dancers and artists had probably done for the culture of Ayutthaya three centuries earlier. The capital of Ayutthaya, now in ruins, is situated some 80 km north of the present capital, Bangkok.

The Early Bangkok Period

Son of a Chinese father and a Thai mother, the future King Taksin was a military officer at the time of Ayutthaya’s fall. Within seven months he managed to rally Thai forces, expel the Burmese, and establish a new capital at Thonburi, further down the Chao Phraya River. In 1782 a revolt broke out against King Taksin. He was replaced by a prominent military commander, Chao Phraya Chakri, the founder of the present Chakri dynasty and later called King Rama I. For strategic reasons he moved the seat of government across the river to a small trading port known as Bangkok.

That was the start of the Bangkok or Rattanakosin period. The most important task for the early Chakri rulers was to re-establish the former glory of Ayutthaya in the new capital. Thus, by royal order, canals were dug to create a replica of Ayutthaya’s city plan in Bangkok, copies of Ayutthaya’s destroyed palaces and temples were built, surviving sculptures were brought from the old capital, and lost literature was recreated.

- Scene from the Ramakien, a detail from an early Bangkok Period black-and-gold lacquer cabinet, Muang Boran Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

King Rama I ordered the manuscripts of three literary works to be rewritten. They were the Tripitaka or the Buddhist cannon, a codification of law and the Ramakien, the Thai version of the Indian Ramayana epic. “The first served to revive the religious order, the second enforced the rule of law and the last served to uphold the monarchic power”. So notes the most recent introduction to the Ramakien-related khon masked theatre, and it continues:

- Hanuman, the magic monkey, in the Ramakien mural of Wat Phra Kaew and on the khon mask-theatre stage Jukka O. Miettinen

From the inauguration of Bangkok as the new capital, the Ramakien could be found in Siamese culture in a fully integrated manner, linking all forms of the arts and artistic expression from books to dramatic presentations and from classical dance to mural paintings. (Khon, Thai Masked Dance 2006, 22)

The Thai Ramakien

- Temple murals give information about the forms of theatrical arts that were popular in the early 19th century. This mural in Wat Matchimawat in Songhkla was painted during the reign of King Rama III (1824–1851)

- Prince Phra Ram (Rama) in a khon performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- The Demon King Totsakan (Ravana) in a khon performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hanuman, the white magic monkey, in a khon performance Jukka O. Miettinen

The Ramakien (Rama’s Story), also known as the Ramakirti (Rama’s Glory), is a localised version of the originally Indian epic, the Ramayana. It describes the life of Prince Rama (Phra Ram in Thai), Crown Prince of Ayodhya and also an avatara of the god Vishnu. His consort Princess Sita (Nang Sida) is abducted by the demon king Ravana (Tosakanth, also Tosakan, Tosachat, Thotsakan) to his island kingdom of Lanka (Longka). The lengthy story recounts the ultimately successful efforts of Prince Rama and his half-brother Lakshmana (Phra Lak), assisted by the white monkey Hanuman and the brave monkey army, to rescue Princess Sita from Lanka.

The Rama stories, of which the Ramakien is only one of the numerous versions, are usually connected with Hinduism but are sometimes also interpreted in the Jain, Buddhist and even Islamic context. Rama’s story was already known in the regions of present-day central Thailand by the end of the first millennium and the beginning of the second millennium AD, when the Khmers ruled parts of the area. The importance of the story is clearly demonstrated by the fact that the capital of Ayutthaya was named after Rama’s city Ayodhya, located in northeast India. Little is, however, known about the manifestations of the Rama tradition during the Sukhothai and Ayutthaya periods.

When the new Chakri dynasty was established in Bangkok, one of the first activities of the first two kings was to have the text rewritten in its now approved classic form. The importance of the epic was further underlined by the fact that the kings were later renamed after the epic hero, as King Rama I and King Rama II. However, the origins of the Thai version and its sources are not known.

It is easy to recognise several specifically Thai qualities in the Ramakien. Phra Ram is, of course, presented as an avatara or incarnation of Vishnu, but at the same time he is subordinate to Shiva. The emphasis lies in the second of the three parts of the story, that is, in the section describing the abduction of Sita and the Great War.

Hanuman, for example, is not celibate and purely devout as in the Indian tradition, but rather a Casanova-like ladies’ man. Thus the story is localised in several ways. For example, the Buddhist connotation can be recognised, although Phra Ram is not regarded as the Buddha or any of his previous incarnations. The epic was, however, compiled by Buddhist kings and the epilogue, written by King Rama II, stresses the connection between the Ramakien and the Buddhist teachings.

By order of King Rama I (1782–1809) Ramakien was compiled to form what is still today the longest composition in Thai verse. In 1815, by order of King Rama II (1809–1824) Ramakien was written in a form suitable for khon and lakhon performances, and later, by order of King Rama IV (1851–1868) several scenes of the epic were rewritten.

One important aspect of the Ramakien is its role in the dynastic cult, which is firmly rooted in the ancient conception of the devaraja or god-king of the Khmer tradition. The King is regarded as the incarnation of Phra Ram, and thus the Ramakien is also the narration of the “Ten Kingly Virtues” of the righteous ruler. J.M.Cadet has written with good reason: “For so successfully indeed has Rama I transmuted the epic…that the majority of Thai know nothing of its Indian origin, looking upon the Ramakien less as a work of art than a history of their royal house” (J.M. Cadet, 1970).

- Ramakien murals in galleries surrounding the Wat Phra Kaew complex in Bangkok Jukka O. Miettinen

The importance of the Ramakien for the dynastic cult is emphasised by the fact that the whole epic was painted by order of Rama I in the galleries of the Wat Phra Kaew or the Royal Chapel in the old Grand Palace of the early Bangkok period. It is the very centre of the dynastic cult enshrining the Emerald Buddha, the palladium of the ruling dynasty. Thus an ancient, probably Khmer-derived, but later Buddhacised god-king cult and the Ramakien tradition were officially amalgamated, which led to the creation of several theatrical traditions regarded as the classical forms still today.

Early Chakri Kings and the Theatrical Arts

- Cremation ceremony of Totsakan (Ravana). This huge mural in Wat Phra Kaew also shows various forms of theatrical performances, which were popular in the royal cremation ceremonies during the 19th century when the mural was painted Jukka O. Miettinen

As mentioned already, King Rama I (1782–1809), to whom the present Thai Ramakien is attributed, founded the still reigning Chakri dynasty and established the present capital in Bangkok. Through skilful diplomacy, concessions, and modernisation, the rulers of the Chakri dynasty were able to preserve Thai independence at a time when all the neighbouring countries fell under Western colonial rule.

King Rama I started the building of Bangkok and its Grand Palace and the adjoining Wat Phra Kaew or the Royal Chapel. Dance masters and other artists were gathered in Bangkok to revive what was left of the artistic traditions of Ayutthaya. The all-female dance-drama lakhon nai was restricted to court use only, while the more popular lakhon nok dance-drama was allowed to be performed publicly.

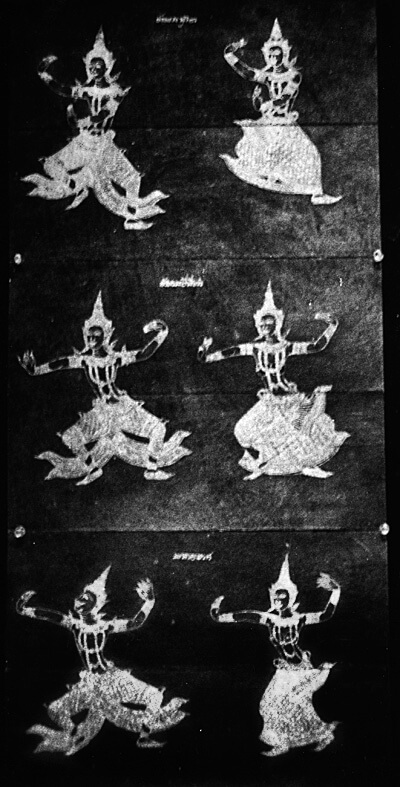

- Early dance manual Jukka O. Miettinen

The rule of King Rama II (1809–1824) is regarded as the golden age of Thai theatrical arts. The king wrote his own versions of the Ramakien and the originally East Javanese story cycle Prince Panji, which was renamed Inao. Classical dance was revived and dance manuals were written and painted, while khon mask-theatre and lakhon nai court dance-drama were standardised.

The rule of the King Rama III (1824–1851) is regarded as a less fruitful time for the theatrical arts. He was deeply religious and he abolished the tradition of court dance-dramas. Many former court dancers were forced to leave the court and earn their livelihood by performing publicly. Thus the echoes of the court dance and dance-drama reached the ordinary audiences as well. Some of the court dancers moved to the court of Cambodia in Phnom Penh to work either as dance masters or as performers.

The first reformist ruler was King Mongkut or Rama IV (1851–1886), “The Architect and Champion of Thai Independence”, who reformed government administration according to Western models. He was also interested in Western science and established the empirical world-view among the educated classes. He revived the khon mask theatre and the court dance-drama lakhon nai again.

His son King Chulalongkorn or Rama V (1868–1910) was the first Thai ruler to visit Europe. He has been called “The Great Reformer” for having abolished slavery, outlawing opium, and reforming the administration. Thai rule extended beyond the present borders of the country, and Thai culture again made its impact on Laos and Cambodia.

The first Western theatre house was built in Bangkok and Western stage realism made its way, to a certain degree, into Thai theatre. Western-style theatre and even opera became popular among the Bangkok urban audience. King Chulalongkorn himself was very interested in theatre and even wrote plays. Among them is Lilith Nitra, which tells about the aboriginal people of South Thailand. Its leading actor was a real “negrito” from the south. Classical performances were shortened, while exotic topics were popular. Plays were written about Chinese and Burmese themes; A Thousand and One Nights and even a Thai version of Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly were staged.