Introduction

- Kutiyattam dance-drama from Kerala, India Jukka O. Miettinen

- Khon dance-drama from Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arja dance-opera from Bali Jukka O. Miettinen

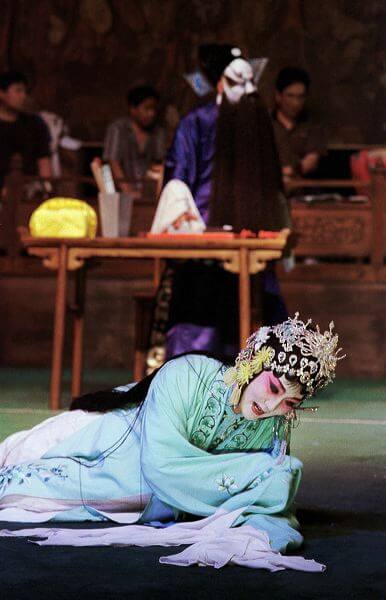

- Kun opera from China Veli Rosenberg

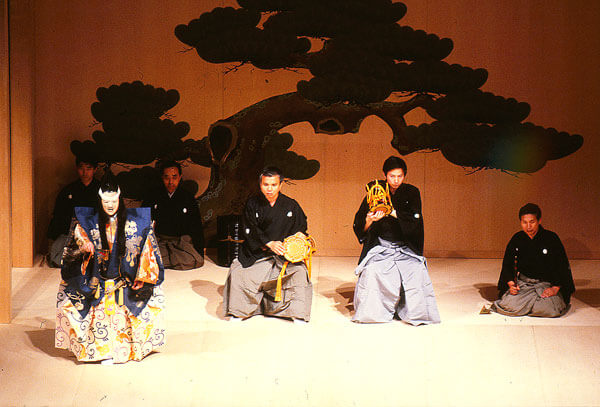

- Noh theatre from Japan Jukka O. Miettinen

- Changguk opera from Korea Jukka O. Miettinen

No “one” Asian tradition of theatre and dance exists; there are at least hundreds of them. Therefore all generalisations about “Eastern” or “Oriental” theatre and dance are usually misleading. However, if we want to compare Asian theatrical traditions with the late 19th to mid 20th century western mainstream tradition, it is possible to find some essential differences, which may be helpful when one is trying to capture some of the characteristics of Asian performing art traditions.

The interrelatedness of drama, dance and music

In Asia drama, dance and music are inseparable. In the European performing arts, on the other hand, they developed their own ways. Thus in the West we talk about text-dominated “spoken theatre”, music-dominated “opera”, and dance-dominated “ballet”.

Most of the traditional forms of Asian performing art combine drama, dance and music into a kind of whole in which it is difficult to draw a clear borderline between these art forms. Most of the Asian traditions employ either dance or dance-like, stylised movements, while movements are frequently interwoven with text. In addition to this, most of the traditions are characterised by their own specific musical styles or genres. The acting technique, which employs dance-like body language, is usually very intricate and it demands many years of arduous training, as western ballet technique, for example, does. Therefore in Asia it is simply not possible to classify stage arts as nonverbal “dance” or “spoken theatre”.

- Hun krabok rod puppet from Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- Rod puppet theatre from Sichuan, China Jukka O. Miettinen

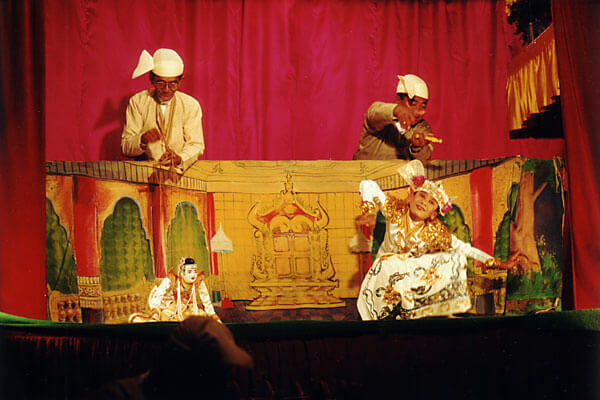

- Burmese marionette theatre Jukka O. Miettinen

- Bunraku rod puppet theatre in Japan Jukka O. Miettinen

- Pavakathakali glow puppet theatre from Kerala, India Jukka O. Miettinen

- A marionette dancer from Sri Lanka Jukka O. Miettinen

The Interaction between “Living Theatre” and Puppet Theatre

In Asia, puppet theatre and one of its variations, shadow theatre, are often regarded as valued “classical” traditions, whereas in the western tradition puppet theatre is, with only a few exceptions, regarded merely as children’s entertainment.

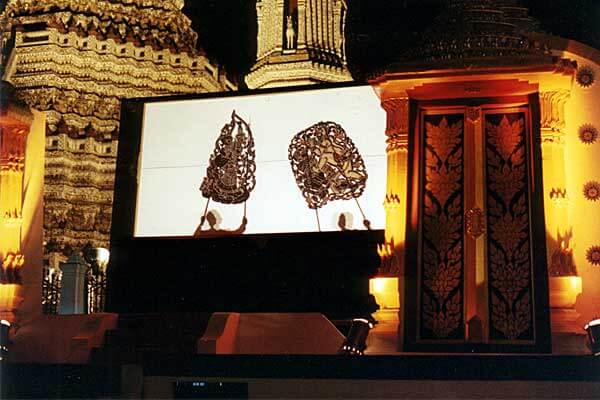

In Asia there are dozens of important forms of puppet theatre. One could generalise that shadow theatre usually represents the early strata of puppetry with a long history and religious or magical connotations. In shadow theatre the silhouette-like figures are often cut from leather or other transparent or semi-transparent materials and they are seen through a cloth screen while manipulated by one or more puppeteers.

The interaction of puppet theatre and “living theatre” is one of the characteristics of Asian theatrical traditions. There will be several clear examples in this book of how puppet theatre has influenced the structure, acting technique and other conventions of “living theatre” and vice versa.

- Indian tolpavakoottu shadow theatre in Kerala, India Jukka O. Miettinen

- Indian tolpavakoottu shadow theatre in Kerala, India Jukka O. Miettinen

- Nang yai shadow theatre from Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- Malaysian shadow theatre Jukka O. Miettinen

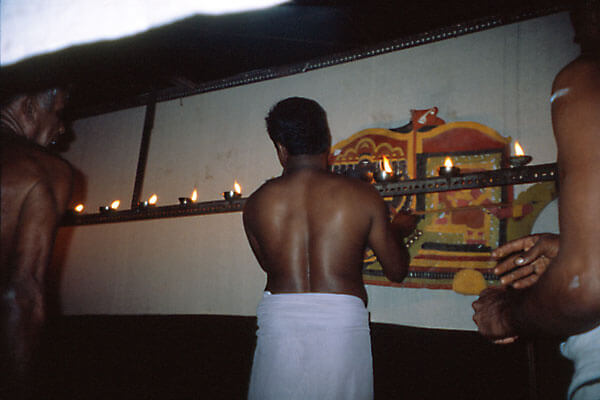

Relationship with Religion

In western tradition, dance and theatre were separated from religion after the Middle Ages. In many of the Asian cultures, theatre and dance, however, are still organically related religions and other belief systems today. This deep intermingling of theatre, dance and religion makes it difficult to draw a sharp borderline between dance, ceremonies and rituals, as will be apparent later.

The Preservation of Ancient Forms

In Europe there are only a very few, if any, really living ancient performing traditions. Western theatrical tradition is firmly based on existing drama texts, some of which are over two thousand years old, but how these texts were originally performed can usually only be speculated upon.

In Asia there is, however, an abundance of theatrical traditions with histories of hundreds, some times even thousands, of years in which the performance traditions with specific acting techniques are also still preserved. This may be due to the deep interrelationship with religion and rituals. Religious art tends to be conservative in nature and changes of style are mainly avoided. Thus Asia is a treasury of traditions representing different stages of the development of theatrical performances from stone-age rituals to later, complex court performances and to modern, often western-influenced styles.

Most of these traditions preserve not only a literary heritage, but also an acting technique, costuming, masks, a make-up system etc. that have retained much of their original qualities throughout the centuries.