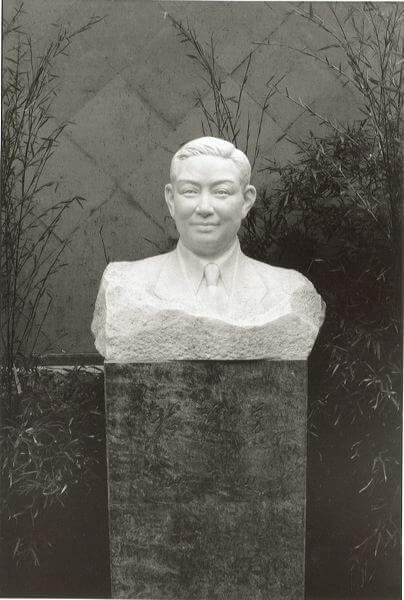

Mei Lanfang

Mei Lanfang (1894–1961) is without doubt the most famous Peking opera actor, both in China and abroad. It was Mei Lanfang who, for the first time, brought Peking Opera to the West, and thus influenced many Western pioneers of early modern theatre. He was born into a Peking Opera actor family that specialised in the dan or female roles. He made his stage debut at the early age of ten.

In 1913 he performed in Shanghai and was a sensation in South China. Although he specialised in traditional Peking Opera, he also experimented with modern drama, inspired by the many innovations of the lively theatre life of cosmopolitan Shanghai.

In the 1910s and 1920s he worked actively in the field of xinxi or “new plays”, in which a famous actor invites a scholar or a writer to adapt an already well-known story into an opera libretto. These kinds of new operas were very popular during the period of the Republic of China. It was also the period of the early flourishing of Western-influenced spoken drama in Shanghai among the rather limited university-educated audience. These modern dramas usually had very concentrated themes, often with patriotic or social overtones. Mei Lanfang, for example, produced a few modern theme-plays that focused on the oppression of Chinese women.

Above all, Mei Lanfang worked with traditional Peking Opera. However, he introduced many new features to its stagecraft and enriched the dan role category further. Together with actor Wang Yaoqing (Wang Yao-ch’ing), he created a new sub-category, the so-called huashan or the “flower robe”. It is a combination of the restrained qingyi or noble lady and huadan or the coquettish woman, in which the actor should master both singing and miming skills, sometimes even acrobatics. Thus Mei Lanfang widened the scope of dan acting.

Mei Lanfang was an art collector and an accomplished amateur calligrapher. His interest in Chinese history led him to create new variations of stage costumes based on prototypes older than the Ming dynasty. He pointed out that an actor should have a sound knowledge of history. He once said: “Of course, an actor should be innovative in his work, but his originality should stem from knowledge. He will not find the right means of expression if he has not studied widely and if he does not know history.”

He also composed several new melodies for Peking Opera and created new dance sequences, still popular today. They include the Satin dance, the Sleeve dance, the Dusting dance, and the Feather dance. In his acting technique he incorporated dance to the extent that practically all his movements could be regarded as dance.

In 1919, Mei Lanfang was invited by the Imperial Theatre in Tokyo to perform there for a month. In the spring of 1930 he went to the United States, where he performed successfully in New York, Chicago, San Francisco and Los Angeles, and was awarded honorary doctorates by two universities.

His visit to the Soviet Union in 1935 was an even greater success. His performances were seen by several important Western theatre reformers, such as Konstantin Stanislavski, Bertolt Brecht and Gordon Craig. Brecht, in particular, together with actor Wang Yaoqing, became deeply interested in Peking Opera and Mei’s art. In his famous essay on Mei Lanfang, Brecht expresses his awe of the articulated technique of Mei Lanfang’s acting. He wondered if there were any Western actors of the period who would be able, after a performance, in a short time and dressed in a tuxedo, to demonstrate the actual fundamentals of his acting technique.

During his career in China Mei Lanfang became a major cultural personality. In 1931, at the beginning of the Japanese invasion, Mei Lanfang promoted patriotism by means of his stage productions in Shanghai. During the Second World War, when Japan occupied part of China, he grew a beard in order not to be able to perform on stage. In 1950 Mei Lanfang moved back to Peking, where he both performed and trained a new generation of actors.

Owing to his achievements and influential position, Mei Lanfang was able to persuade Mao Zedong and the Communist Party not to ban Peking Opera. Although Peking Opera went through several “reforms” during the early decades of the new regime, it has been taught and performed continuously until now, with the exception of the Cultural Revolution in 1966–1976.

- A portrait of Mei Lanfang, the most well-known Peking opera actor of the 20th century. Mei Lanfang Museum, Beijing