Nang Yai, Theatre of the Large Shadow Figures

- Nang yai puppeteers operate figures cut out of leather Marja-Leena Heikkilä Horn

Nang yai (“large puppet”) is an ancient form of shadow theatre in which dancing puppeteers perform scenes from the Ramakien by presenting cut-out leather figures against a semi-transparent cloth screen. In the latter part of the 20th century it became very rare but attempts have recently been made to revive it.

The Question of its Origin

The origin of shadow theatre is a standard problem in Asian theatre studies, as it has been performed over a wide area from Turkey in the west to China in the east. Similarly, the origin of nang yai is one of the widely discussed topics in Thai theatre studies. One could summarise by saying that there seem to have been several attempts to explain the origins of this unique form of shadow theatre.

According to a popular theory, nang yai originates from South Thailand and was received there through the Srivijaya Empire. It could also have been transmitted via the sea routes directly from India, which is often regarded as the cradle of many of the Southeast Asian shadow theatre traditions.

The problem with this theory, however, is that no Indian or any other Southeast Asian shadow theatre traditions employ similar, static picture-like images as used in nang yai. Moreover, in no other tradition in the whole of Asia do the puppeteers dance while operating the figures as is the case in nang yai. The only “sister” form with similar practices is sbek thom in Cambodia, which is discussed in connection with Cambodian theatre.

Early surviving nang yai figures, which were made during King Rama II (1809–1824), show a variety of stylistic features, such as the mask-like faces of the demons and monkeys, which clearly relate them to the Ramakien imagery of the Central Plains of Thailand. Whatever the origins of nang yai are, it is self-evident that it is organically interwoven into the Thai Ramakien tradition as a whole.

Nang yai is the earliest theatrical art form mentioned in Thai literary sources. The Ayutthaya Palatine Laws of the 14th and 15th centuries mention nang yai on several occasions. This indicates that nang yai must indeed have been well-established even by then. There even exist references indicating that nang yai may have been performed during the Sukhothai period, but since these references belong to the fictional literature of later periods, scholars have been very cautious in accepting this as a fact.

Dancing Puppeteers

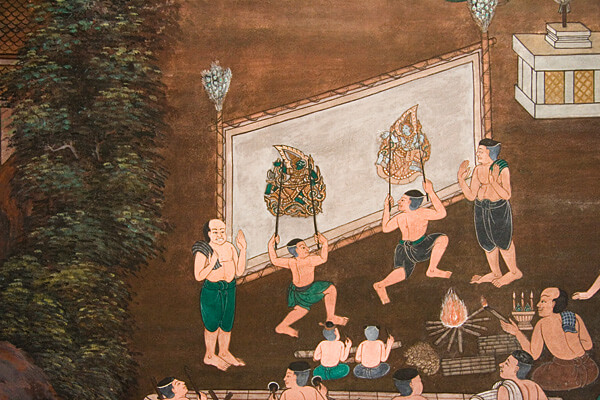

- Nang yai performance in the Ramakien murals of Wat Phra Kaew Jukka O. Miettinen

- Old nang yai puppets in an exhibition at the Bangkok National Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

The nang yai is an exceptional and clearly very archaic form of shadow theatre. In most Asian shadow theatre genres the puppets are rather small human figures, cut-outs, often with movable limbs. The nang yai puppets, on the other hand, are large, 1–2 metres oval or almost round non-articulated leather silhouettes, in which the characters from the Ramakien are engraved as if in a frame.

A large screen, 7–10 metres wide and some 3 metres high, is erected on poles approximately 2.5 metres above the ground. In front of the screen are often the musicians of the traditional Thai piphad orchestra, consisting of oboes, xylophones, gong sets, and other percussion instruments. Sitting and sometimes standing among the orchestra are two narrators, who recite and sing the text enacted by the silhouettes on the screen.

The puppeteers move with their figures both in front of the screen and behind it. In Asian puppet theatre the puppeteer usually has a distinctly vocal role, often reciting and singing the lines. In nang yai the manipulator acts merely as a dancer, supporting the large leather figure with two rods in his hands.

The dialogues and long palace scenes appear to be static, but in action scenes, the manipulator dances to musical tones of the accompaniment reflecting various moods and situations. His movements and positions, seen by the audience from under the screen, must correspond to the character of the figure he holds. Heroes express restrained masculine energy, demons have strong, open movements while princesses move gracefully. The nang yai is thus a complex art form, combining figurative art, the stock melodies of Thai theatrical music, and the art of singing, as well as dance movements.

From Court Theatre to a Rarity

Nang yai is supposed to have originally been court theatre with many religious and ritual features. Making the puppets and holding an actual performance involved many ritual features. Nang yai plays were performed in the evening by the light of coconut-shell fires. The evening performance was sometimes preceded by a prologue in the afternoon, the nang ram (nang rabam), which was performed in daylight.

In the latter, the puppets were painted in bright colours, while puppets for the evening performances were less colourful. Common to both types of puppets is their decorative style, deeply related to the aesthetic principles of the visual arts of the late Ayutthaya and early Bangkok periods. The leading characters are often depicted as individual figures sitting, walking, fighting etc. The larger figures may include Rama in his chariot, couples such as combatants or lovers, or even complete scenes.

In the latter half of the 20th century, nang yai was in danger of extinction, as it was performed by only one group of aged puppeteers outside Bangkok. The College of Dramatic Arts in Bangkok and its sub-branches around the country have been trying to maintain the tradition as a part of classical dance-drama, particularly in the play Inao, in which it is performed as a play within a play.

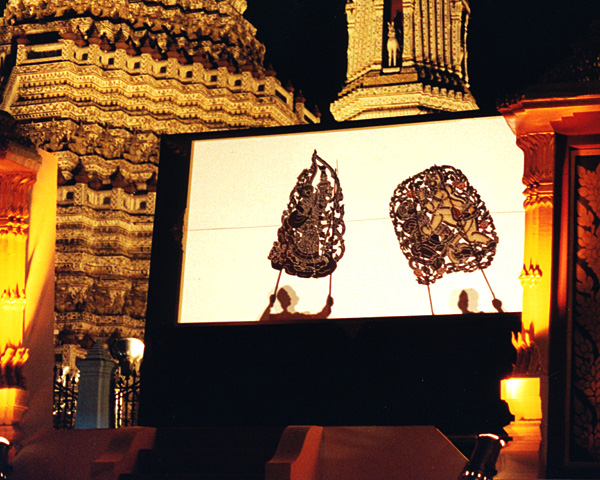

- A nang yai performance at the Wat Arun Festival, near Bangkok Jukka O. Miettinen

In the late 20th century and the early 21st century nang yai is every now and then performed at theatre festivals, and fear of its extinction is no longer so acute. In contemporary productions, which combine traditional forms with innovations, nang yai is sometimes combined with dance and other theatrical forms.