Thai Classical Dance

- Classical dancers at the Bangkok National Theatre Jukka O. Miettinen

The present Thai classical dance (natasin) probably developed during the Ayutthaya period (1350–1767), although very little is known about the process. Its roots can be deciphered by using the early dance images of the region, already discussed above, as archaeological source material. The possible origins of Thai dance may be found in the Khmer tradition as depicted in the dance images in the Khmer reliefs of Angkor and the Khmer-related reliefs of the Phimai temple in eastern Thailand.

- The dance of the half-human, half-bird kinnaris reflects ancient animal movements Jukka O. Miettinen

One source may be the Mon tradition, depicted in the few surviving Mon reliefs. One possible transmission route for this clearly Indian-influenced dance technique could also have been South Thailand with its connections with Sri Lanka and the Srivijaya Empire. There may also be the possibility that the dance tradition was brought from India direct to the regions of Thailand by Indian Brahman gurus.

Indian Influence Localised

This last possibility is supported by the fact that many dance-related key terms still used in the Thai language, such as natasin (classical dance) and kru (guru), stem from Sanskrit and are related to India’s Natyashastra dance and theatre manual (Natasatra in Thai). Furthermore, a Sanskrit manuscript of a Natyashastra manual can be found in the National Library of Thailand. The Thai dance technique has indeed many features in common with Indian techniques. They include several poses, the use of three different speeds of movements, and the original series of 108 basic movements (now reduced to 68) corresponding in number to the 108 karanas of the Natyashastra. However, there are also definitive differences between the Indian and Thai traditions, as the Thai scholar Mattani Rutnin has noted:

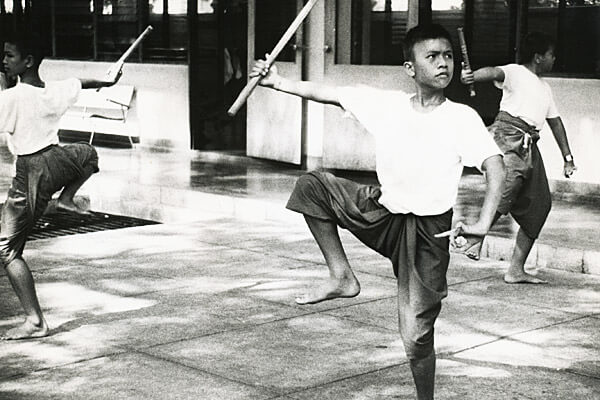

- Noble heroes make full use of classical Thai dance. Training at the Drama College in Bangkok Jukka O. Miettinen

Thai dancers, in both the folk and classical styles, hold their bodies straight from the neck to the hips in a vertical axis and move their bodies up and down with their knees bent, stretching to the rhythm of the music. Indian dancers, on the other hand, often move their bodies in an S curve. The arms and hands in Thai dancing are kept in curves, or wong, at different levels, high medium or low, and the legs are bent with the knees opening outward to make an angle called liem (lit., angles) … The grace and beauty of the dancer depends on how well these curves and angles are maintained in relationship with the proportion of the whole body. (Mattani, 1993)

Furthermore, Mattani adds that the Indian mudras are simplified in Thai dance to a few basic hand gestures, which when combined with dance gestures (phasa ta), can denote the actions and, especially, the moods of the characters. She also notes that the foot movements of Thai dance are generally slower than in India and, furthermore, that in Thai dance the toes are mostly curved upward or kept flat at an angle with the legs, but never pointed, as they sometimes are in Indian dance. These differences may be interpreted as signifying that the Thai adopted their dance tradition, not directly from India, but from their neighbours, the Khmer and the Mon, in an already localised form.

Role Categories

The present classical Thai dance surely developed during the Ayutthaya period, but very little is known about this process. According to the Thai scholar Mattani Rutnin the classical court dance tradition declined towards the end of the Ayutthaya period, but the remains of the tradition were, nevertheless, carried over to the court of the new capital by two Auytthaya princesses. The formulation of the present style took place during the reign of Rama I (1782–1809). The standards were set by the principal master of the Royal Lakhon troupe, Chaofa Krom Phra Phithakmontri, who is still worshipped as one of the great masters of dance in a traditional wai kru invocation ceremony, which will be discussed later.

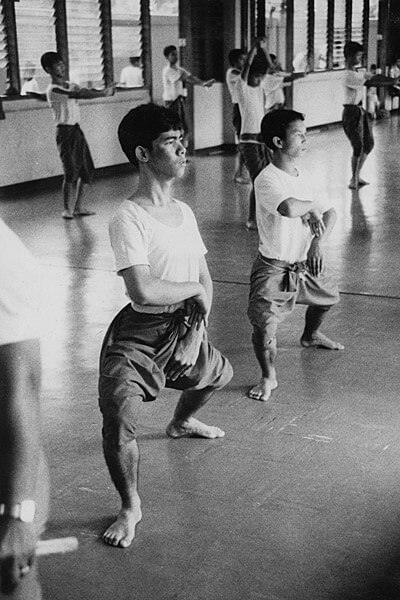

- Training of the dance technique of the noble male characters Jukka O. Miettinen

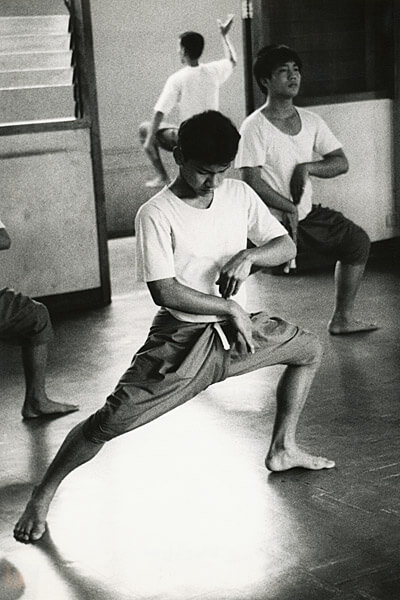

- Training of the dance technique of the noble heroines Jukka O. Miettinen

Thus, standardisation of the dance technique happened exactly simultaneously with the rewriting of the Ramakien and with the creation of the dynastic Rama cult of the Bangkok period. It is no wonder that the sub-techniques of classical Thai dance are classified according to the characters portrayed in the Ramakien. The first group, the noble humans, are divided into major heroes (Phra Ram), minor heroes (Phra Lak), major heroines (Nang Sida), and finally to minor heroines (Montho). It is interesting to note that even the names of the role categories are taken from the Ramkien’s principal figures. The second group consists of demon characters (yak), and the third monkeys (ling), both also central to the Ramakien.

Technique

Dance students usually start their training between eight and ten years of age. In the first phase all of them study the fundamental series of movements, the so-called “slow movements” (phleng cha) and “fast movements” (phleng reo). They then proceed to study the basic movement patterns for each role type corresponding to the individual student’s physique. Heroes should be well proportioned and stately in bearing, demons athletic, while monkeys should be short and acrobatic.

For the refined characters (Phra and Nang) there were originally 108 basic movements, but later they were reduced to 68 movements in the major movement series (mae bot yai) and to 18–20 in the smaller series (mae bot lek). The dance of heroes and heroines represents Thai classical dance in its most complex form. It makes full use of the meaningful and elegant hand gestures, echoing the Indian mudras. The steps are light. The bare soles of the feet rarely touch the ground, while the toes are often turned upwards. As in India and in most South-East Asian traditions, bare footedness is a ritual feature, as the stage and the actual performance are regarded as sacred.

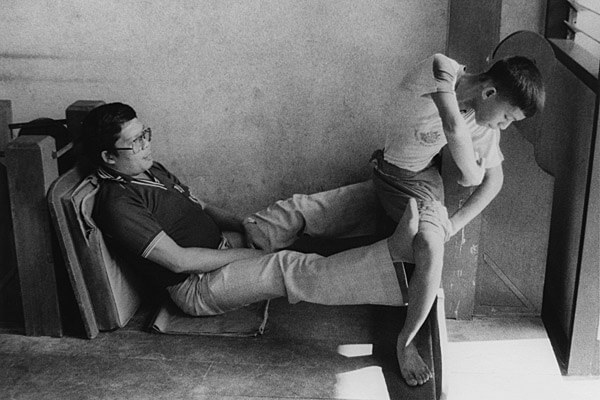

- A teacher helps a student to gain the proper open leg position Jukka O. Miettinen

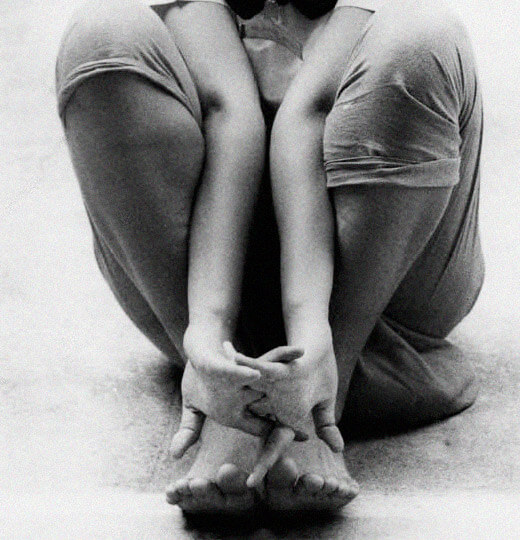

- Training of the flexible arms Jukka O. Miettinen

The demi plié (lim) of the legs permits the characteristic flexibility of movement, the shifting of weight from one side to the other, and the small, jerky accents of the dance, while the shoulders and upper torso are kept straight. The slow dance of the noble characters, however, emphasizes the delicate movements of the arms and hands. These are trained from the very beginning by bending the fingers backwards to create the unnaturally elegant finger gestures, already depicted in the early Khmer reliefs and later in Thai art. The arms are trained by pressing them between the knees until the softly curving shape is achieved (liem). The noble characters have not used masks in any style of dance drama since the end of the 19th century. They keep their faces, though, almost expressionless.

- Training of the dance technique of the monkeys Jukka O. Miettinen

- Training of the dance technique of the monkeys Jukka O. Miettinen

- Training of the dance technique of the demon characters Jukka O. Miettinen

- Training of the dance technique of the demon characters Jukka O. Miettinen

The monkey and demonic characters, on the other hand, have their own basic series of movements. They have six patterns of movements, of which the monkey’s movements were later reduced to five. The technique of both role types is dominated by an extremely open leg position, the Indian-influenced characteristic of Southeast Asian martial dance. In fact, the demons’ movement technique has its roots in ancient martial arts. Thus the demons’ dance is aggressive, whereas the monkey’s dance has its acrobatic and playful elements. Their movements imitate those of real monkeys and thus add to this complex movement system one more element, that of the very ancient animal dances.

Thai Style in Cambodia

This dance technique and its repertoire were also adopted in Cambodia during the long period of Thai domination which had already started in the 14th century and ended in 1907, when the Thais returned the province of Siem Reap (where Angkor is located) to the Cambodians. Dance masters from the Thai court are known to have trained the Cambodian Royal ballet even during the period of Rama I (1782–1809), and the co-operation of the Cambodian and Thailand’s National dance companies still continues today.

Types of Dance

- Folk dance performed by the dancers of the Drama College in Bangkok Jukka O. Miettinen

- Folk dance performed by the dancers of the Drama College in Bangkok Jukka O. Miettinen

There are several terms in the Thai language referring to different types of dance: natasin refers to classical Thai dance, whereas rabam phun muang refers to folk dances. The ancient word rabam by itself refers to “choreographed dances for specific functions and occasions”, whereas a similarly ancient term ten indicates “dancing with emphasis on the hand movements”

- Dance ritual performed in a temple in Lopburi Jukka O. Miettinen

- Spirit possession dance performed in northern Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- Spirit possession dance performed in northern Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

According to conservative estimates, there are over a hundred different dance traditions in Thailand. Many of these are archaic dance rituals or folk dances, belonging to the heritage of ethnic minorities. The traditions can be roughly classed into four main groups: the above described central, northern, northeastern and southern styles. In all Thai dancing, the emphasis is on the movements of the arms, hands and fingers. The local traditions, however, differ in style.

The Central Thai style, discussed above, has been maintained since the Revolution of 1932, which overthrew the absolute monarchy, mainly by the Witthayalai Natasin or College of Dance and Music with its several branches around the country, and by the National Theatre in Bangkok. The technique is canonised in manuals, of which the earliest existing are the early Bangkok period manuals preserved at the National Library of Thailand.

- A folk dance from northeastern Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- A nora-style dancer from southern Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

The northeastern style of the regions of Isaan incorporates fewer finger movements compared with the classical style or the dynamic southern nora dance, which is characterised by a very open leg-position and expressive finger movements. The northern style of the former Tai kingdom of Lanna is often slow in a legato-like manner.

- Central Thai classical dance inspired by the southern style Jukka O. Miettinen

- Central Thai classical dance inspired by the southern style Jukka O. Miettinen

Traditionally, the classical style of Central Thailand has dominated Thai dance, dictating the standards according to which other dance styles have been adapted and developed in universities and art colleges. Recently, however, there seems to be going on a kind of revival of local styles, which are now also studied and interpreted in their more original forms. The “revival” of the northern Lanna style has been remarkable in the circles around Chiang Mai University.