The Tang Dynasty (618–907)

The International Golden Age

The Tang dynasty is often regarded as the classical period of Chinese civilization. It was a relatively peaceful phase in Chinese history. Literature, the visual arts, and music flourished and the theatrical arts were evolving towards their present forms. The most influential capital of the dynasty was Changan (C’hang-an) (currently Xi’an, Hsi-an) in Central China. During the Tang dynasty it was the world’s biggest metropolis. A vast network of caravan routes, generally known as the Silk Road, connected Changan with Central Asia, India, Persia and finally with the Mediterranean world. The influence of Tang culture spread to Korea as well as to Japan, where two of its capitals, Nara and Kyoto, were built according to the city plan of Changan.

- The Tang-dynasty tomb terracotta statues give much information about the history of dance. Jukka O. Miettinen

Buddhism, brought from India via Central Asia, became the dominant religion. Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism and later Islam were also practised. During liberal times they lived peacefully side by side with the traditional indigenous belief systems and ideologies, Taoism and Confucianism. In the visual arts the pan-Asian Buddhist style was combined with the refinement of Tang court elegance. Tang China was open to outside influences and the trade routes brought to Changan monks, scholars, artists, musicians and dancers from all over the then known world.

- The Tang-dynasty tomb terracotta statues give much information about the history of dance. Jukka O. Miettinen

Changan, with its approximately one million inhabitants, was a well organised cosmopolitan city, where international embassies and traders had their own, designated quarters. The city bustled with Central Asian horsemen, international traders, many in their national costumes, as well as elegant beauties with tiny, painted lips, all of them immortalised in the Tang-period terracotta statuettes. The terracotta figurines also give enlightening information about the many forms of music, dance, mimes and other entertainment which were in vogue during that time.

Court Performances

Earlier theatrical forms were further developed during the Tang period. However, the traditional ceremonial chorus dances with their large orchestras were also performed. Their stories included, among others, earlier play scripts, such as Mask and The Dancing, Singing Wife. Perhaps echoes of these kinds of ceremonial performances can still be captured in the Japanese bugaku court dances. Acrobats, jugglers and clowns, on the other hand, entertained the audience in the less serious spectacles, as had been the case in the earlier baixi or hundred entertainments shows.

The spectacles could reach megalomaniac proportions. Literary sources mention a performance organised in the 7th century in honour of a Turkish embassy from Central Asia. There were some 30 000 spectators. On the stage, which covered a square kilometre, acrobats, magicians and dancers demonstrated their skills. There were even grander shows. Literary sources mention a festivity with 18 000 performers and, it was told, the accompanying music was heard kilometres away.

With its keen interest in other cultures, the Tang court received musicians and performing arts groups from many regions. Several terracotta statuettes show Central Asian performers and the court annals record visitors from even farther away. Southeast-Asian groups were popular and it is known that performances by a Pyu group from present-day Myanmar was greatly appreciated at the court in the 7th century. At approximately the same time a group of Champa dancers, from present-day Vietnam, was employed at court.

Indian music was said to have accompanied a grand-scale court dance performance called Costumes decorated with feathers of the colours of the rainbow. The graceful swings and spins of the colourfully dressed dancers were greatly applauded by the court annalists. More serious scholars, however, had a critical attitude towards these kinds of mass spectacles.

The scholarly audience preferred intimate performances with artistic refinement. Dances were divided into two groups, energetic jian (chien) dances and softer ruan (juan) dances. The dances of the former group were often based on the martial arts or the traditions of foreign nations and they were frequently performed by male dancers. The soft ruan dances were performed by female dancers and these small-scale performances often took place at the intimate parties of connoisseurs.

The “Adjutant Plays” and Early Story Material

At court a new form of entertainment gained popularity. It was the so-called canjun xi (ts’an-chün hsi) or the adjutant play, which probably evolved from earlier, more or less loose, clown and jester numbers. It consisted of short comic skits and featured two comic characters, a more or less dumb courtier, canjun (ts’an-chün), and a slightly cleverer character, canggu (ts’ang-ku). The “adjutant play” has been seen as a forerunner of the fixed role categories of later Chinese opera and particularly of its comic chou characters.

- Storytelling is one of the root traditions of Chinese theatre. Usually storytellers have performed in teahouses. The actual storyteller accompanies himself with clappers and a string instrument while a musician plays a pipa lute. Jukka O. Miettinen

The Tang period was also the golden age for literature and many romantic stories. Buddhist legends and miracle stories were also popular. The Indian influence was strongly present, which is clearly indicated by the fact that a manuscript of the famous Indian Sanskrit play Sakuntala has been found in China.

- The Journey to the West, featuring the popular Monkey King, is one of the most popular stories in China. Here the main characters of the story as shadow puppets, a Buddhist monk, the Monkey King and the pig-headed assistant. Jukka O. Miettinen

The influence of the Indian epic Ramayana can be traced in the stories about the beloved (and yet anarchistic) Sun Wukong (Sun Wu-k’ung) or the Monkey King. He is a central character in originally orally transmitted stories centred on the Buddhist monk Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang), who travelled to India in order to obtain sacred Buddhist manuscripts. Later in the 16th century the stories were collected in a book called A Journey to the West, Xiyou ji (Hsi-yu chi), by Wu Chengen (Wu Ch’eng-en). The most colourful travelling companion of the monk Xuanzang is the Monkey King, who even today is the playful hero of many later operas, shadow and puppet plays, cartoons and animations.

The Fusion of Singing, Lyrics and Prose

The merging together of several literary forms such as lyrics and colloquial language seems to have happened for the first time in the didactic Buddhist stories introduced by Buddhist monks in connection with their missionary work. Verses were combined with colloquial prose in order that the ordinary audience could fully comprehend the morality of the stories. The monks, who were the storytellers, employed different devices to visualise their stories, such as picture rolls or panels, a tradition with its roots in early India, from where Buddhism was adopted.

Emperor Ming Huang and the School of the Pear Garden

One of the most illustrious emperors of the Tang dynasty was the emperor Ming Huang (who was called Xuanzong (Hsüan-tsang) when he came to power, 712–756). He was an active patron of the arts. At his court he had several orchestras, dancers and actors including Central Asian artists.

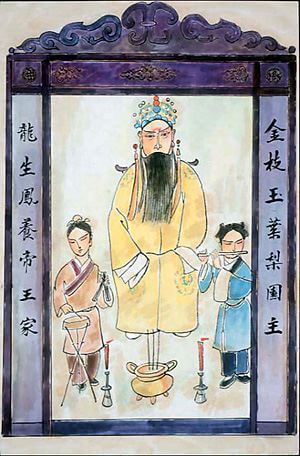

- A stylised portrait of the Tang-dynasty emperor serves as protector of the art of theatre in the old theatre houses. The actors used to pray in front of it before the actual performance. Veli Rosenberg

From the beginning of the Tang dynasty it was customary to have two state offices for administering the training of performers needed in official rites and ceremonies. In addition to these two offices, Ming Huang founded a third school, which trained musicians, dancers and actors. It is generally regarded as the first “theatre school” in the history of China, although in reality it probably concentrated on Buddhist ceremonies. According to tradition emperor conceived this idea from a dream he had had in which he visited the moon, where he saw performances of heavenly musicians and dancers.

The school got its poetic name Liyuan (li-yüan) or the Pear Garden from the location in which it was established in the palace grounds. Even today actors and actresses may call themselves “the children of Pear Garden”. At the school, it is said, the training was occasionally overseen by the Emperor himself. Ming Huang is still today regarded as a kind of patron god or spirit of the art of theatre and his small portrait was often placed at the lower part of the stage, in front of the audience.

Besides the emperor Ming Huang, his dear concubine Yang Guifei (Yang Kuei-fei) is also immortalised by Chinese literature and theatre. The Emperor’s love for her, which nearly caused the collapse of the whole empire, is the subject of many poems and plays. Their tragic love is described in a 17th century play called Changsheng dian (Ch’ang-sheng tien) or The Palace of Eternal Love.

Another side of the concubine’s personality is portrayed in a popular drama script called Guifei zui jiu (Kuei-fei chui chiu) or The Drunken Concubine. It relates the events of an evening when the Emperor leaves Guifei alone in order to have an encounter with another girl. The angry Guifei consoles herself by drinking and the play concentrates on describing the different stages of her drunkenness.

In the turmoil of Chinese history, the Tang dynasty shimmers as a kind of lost Golden Age. It was a period when China was exceptionally open to outside influences. Many forms of Chinese culture, such as poetry, music and painting, produced masterpieces still regarded as classics. As has been discussed above, theatre and dance also flourished. Ming Huang founded his theatre school, adjutant plays experimented with fixed role categories, and, according to some scholars, Chinese dance had already attained its quintessential characteristics.