The Yuan Dynasty (1279–1369)

The Heyday of Chinese Drama Literature

Northern China was under the dominance of the Mongol warlike nomad-civilization from c. 1215 onwards, and the whole country came under Mongol rule in 1279. During this new dynasty, the Yuan (Yüan), the Chinese themselves became despised in their own country. Lowest was the status of the inhabitants of the regions south of the Yangzi River, although the region had been both economically and culturally very important.

The institution of imperial examinations for scholar-officials, so crucial for the administration and cultural life of the empire, was abolished. Thus the scholar officials could no longer participate in the country’s affairs. In former times the Confucian literati formed the elite, but now they were regarded as one class lower than prostitutes and only a grade higher than beggars. The foundation of Chinese society was shaking.

Yuan zaju

Many of the frustrated scholar-officials focused their energy on the arts. The theatrical styles shaped in the Song dynasty became extremely popular. Through the theatre one was able to explore matters common to all: the cruelty of the conquerors, the tragedies of the war, the separation of families or lovers etc. While reflecting the collective sentiments, theatre was able to serve as a form of passive resistance

Censorship was, however, merciless. In order to avoid the death penalty, which was the result of any kind of direct criticism, the writers turned for their material to old stories from the country’s long history or to popular legends and to early, simple plays. The underlying message was, however, clear to their audiences.

The scholar-writers of the Yuan dynasty created high-quality dramatic literature, which is still regarded as classic and is still performed in various later styles. They are shorter than the earlier zaju plays. They usually consist of four acts and sometimes kinds of “prologues” or “interludes”, which, however, form an integral part of the whole. More role categories were employed by the Yuan dramas than the earlier zaju and nanxi traditions. They include

Mo, or male characters

zhengmo (cheng-mo), singing male lead

fumo (fu-mo), supporting male character

xiaomo (hsiao-mo), young man

chongmo (ch’hung-mo), a kind of narrator or a master of ceremonies

Dan (tan), or female roles

zhengdan (cheng-tan), singing female lead

fudan, waidan, tiedan (fu-tan, wai-tan, ti’eh-tan), supporting female characters

laodan (lao-tan), old female character

xiaodan (hsiao-tan), young woman

huadan (hua-tan), coquette female character

chadan (ch’a-tan), intriguer

Others

jing (ching), evil or comic characters

za (tsa), supporting minor characters, such as servants, crooks or children

- A mural from a temple in the Shanxi province, dated 1324. It shows zaju actors and musicians. The Archives of Finland–China Society

An early 14th century temple mural shows a troupe of actors from the Yuan period. The stage has a silken back curtain and the actors wear handsome costumes reflecting their social status. The costumes are, however, not as pompous as the later Peking Opera costumes. The mural also depicts musicians among the actors, a flautist and a percussionist with his clappers.

Yuan zaju play scripts

The names of about a hundred Yuan dramatists have come down to us, and the titles of seven hundred plays are known. The flourish of Yuan drama centred mainly in North China and the then capital, Beijing. The Yuan plays were written to be sung and acted. The language used was mainly the vernacular of its day but the sung “arias” employed sophisticated lyrics. 171 complete Yuan dramas are known today.

Video clip: Liuzi opera Veli Rosenberg

The northern zaju was the style in which these four-act dramas were performed. The music also presented the Yuan zaju style, which unfortunately is lost. At the beginning, one of the supporting characters explained the plot to the audience, after which the leading actors appeared. Only the leading actors sang. Singing, acting, mime and drama merged together, forming an operatic whole.

The most famous of the Yuan dramatists were “The Four Yuan-Period Masters”, Guan Hanqing (Kuan Han-ch’ing), Ma Zhiyan (Ma Chih-yüan), Bai Pu (Pai P’u), and Zheng Guangzun (Cheng Kuan-tsun). The earliest of them, Guan Hanqing, is regarded as the “Father of Chinese Dramatic Literature”. Another important Yuan period dramatist was Wang Shifu (Wang Shih-fu), who wrote the famous Romance of the Western Chamber, Xixiang ji (Hsi-hsiang chi).

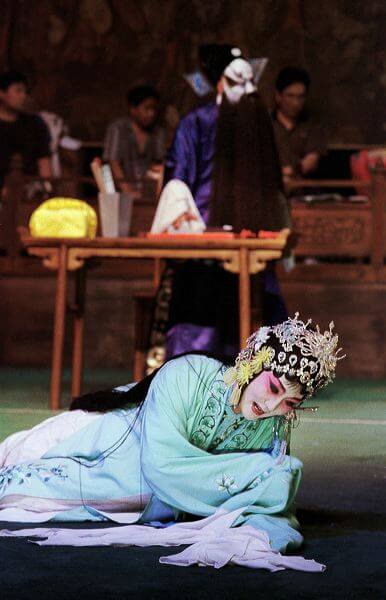

- Dou E hears her death sentence. A kun-style reconstruction of 13th century play, Dou E yuan or Snow in Midsummer by Guan Hanqing. Veli Rosenberg

Guang Hanqing or the “Father of Chinese Dramatic Literature” often portrayed in his crime stories, as did also other Yuan dramatists, mistreated prostitutes and beauties in distress. One of the most famous plays of this genre is Guan Hanqing’s Dou E yuan (Tou Eh yüan), The Injustice Experienced by Dou E or Snow in Midsummer.

Video clip: Dou E. A kun-style reconstruction of 13th century play, Dou E yuan or Snow in Midsummer. Veli Rosenberg

Most of the Yuan dramatists came, as mentioned, from the class of the scholar-officials. Bai Pu (1226–1306) was a son of an impoverished civil servant family. His best-known play is Wutong yu (Wu-t’ung yü) or Rain on the Pawlonia Tree. It tells the tragic story of the love of the Tang emperor Ming Huang and his concubine Yang Guifei amid the political intrigues and power play while the Tang dynasty was nearing its end.

- The opera Pavilion of Eternal Love tells about the tragic love of Tang-period emperor Ming Huang and his concubine Yang Guifei. Here they travel on carriage, a kun opera performance in the northern kun style. Jukka O. Miettinen

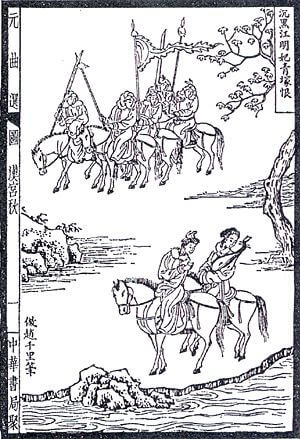

Besides historical stories, stories about the supernatural also often served as the material on which the Yuan dramas were based. One example of an early Taoist-inspired ghost opera is Qiannü lihun (Ch’ian-nü li-hun) or Ciannun sielu irtoaa ruumiista. It was written by Zheng Guangzun (1280–1330) and is based on a story from the Tang period. Yuan dramatis could explore several story genres. Ma Zhiyuan is famous for his Taoist themes, but his well-known play Hangong qiu (Han-kung ch’iu) or Autumn in Han Palace, is based on an ancient, tragic love story with patriotic overtones. It has been one of the most beloved Yuan dramas.

- A Ming-dynasty wood block print showing the tragic final scene from Ma Zhiyuan’s play Autumn in Han Palace. The Archives of Finland–China Society