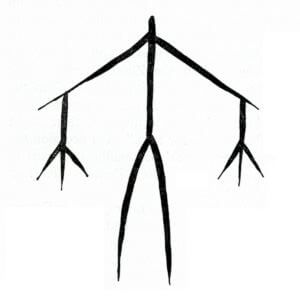

The Early History of Chinese Theatre

- An over three thousand year old Chinese character indicating dance.

- The present Chinese character indicating dance.

As elsewhere in the world, it is also in China that the origins of the theatrical arts seem to lie in early religious rituals, in China most probably in shamanistic rites. China has always been an exceptionally history-conscious culture with a long continuity, and the Chinese system of writing was invented very early. Thus it is no wonder that a relatively substantial amount of written evidence of the theatrical tradition exists from the early periods. It gives enlightening, yet fragmentary, information about the development of early performance traditions.

- The Monkey King is the beloved anarchist from many Chinese operas Jukka O. Miettinen

It is known that during the Shang dynasty (c. 1766–1066 BC) hunting dances as well as dances imitating animals were performed. As has been already discussed on several occasions, the dances imitating animals and employing the so-called “animal movements” have been common in most cultures. In fact, animal movements still form an integral part of many martial art, dance and theatre traditions today.

The so-called chorus dances were popular during the Zhou (Chou) dynasty (c. 1066–221 BC). They were divided into two groups: wu dances performed by men and xi (hsi) dances performed by women. Besides religious rituals, there were less ceremonial types of performances, such as comic numbers performed by clowns and dwarfs as well as displays of acrobatic skills.

Martial art demonstrations or shows were popular and, as elsewhere in Asia, in China, too, many of the movements employed by dances originated from the martial art techniques. It seems most probable that the early martial art systems formed the basis from which the rich tradition of Chinese martial operas and their acrobatic fighting scenes as well as the 20th century gongfu (kung-fu) movies later developed.

Baixi or “A Hundred Entertainments”

Before the beginning of our era it was customary at the court and at public festivities to organise grand-scale spectacles called baixi (pai-shi) or a hundred entertainments or hundred games circus. They were kinds of variety shows featuring mimes, jugglers, magicians, acrobats, song, musical recitals, and martial art demonstrations. They also featured dancing girls wearing dresses with long, fluttering silk sleeves. Their dances may have been the predecessors of later opera scenes, in which female characters elegantly operate their extra long white silk sleeves, the so-called “water sleeves”.

- An earthen tile from the Han dynasty, c. 1st century BC showing a long-sleeved dancer. The Archives of Finland–China Society

- The Tang-dynasty tomb terracotta statues give much information about the history of dance. Jukka O. Miettinen

- The Tang-dynasty tomb terracotta statues give much information about the history of dance. Jukka O. Miettinen

Besides the textual sources, there exists a great deal of visual evidence of early theatrical forms. Contemporaneous terracotta tomb statuettes include hundreds of lively depictions of different kinds of performers. They show mime actors, acrobats, jugglers, musicians, sometimes even whole orchestras, and, of course, dancing girls with their flying sleeves. These female statuettes seem to indicate that the aesthetics of female dances in China, which is dominated still today by linear beauty created by sleeves, ribbons and scarves undulating in the air, has an extensive history indeed.

The Early Plays

Early dramas combined mime, stylised movement and a chorus. The chorus described the action which was enacted by dancer-actors. A play called Daimian (tai-mien) or Mask tells about a prince whose features were so soft that he was obliged to wear a terrifying mask in battle in order to scare the enemy. Later, in the Tang (T’ang) (618–907) period the play also found its way to Japan.

A play called Tayao niang (t’a-yao niang) or The Dancing, Singing Wife comes from the 6th century AD and is a story about domestic violence. The husband is a drunkard, who beats his poor wife. Finally, however, he is punished for his misbehaviour. From Central Asia or even from India originates a dance play called Botou (Po-t’ou) or Head for head. It is about a youth whose father was killed by a tiger. The youth, in a white mourning costume, wanders a long way over the hills and through the valleys in search for the killer tiger. During his wanderings he sings eight songs and is finally able to avenge his father’s fate.

The play scripts of those early dance plays, which also seem to combine sung passages, are now known mainly through sources from the Tang period (618–907). Studying them is a kind of detective work where textual sources are used side by side with visual ones. Possibly some of the characteristics of later Chinese operas can be traced back to these early plays.

The fighting scenes appear to originate in the early martial arts systems, whereas the female movement vocabulary of later operas has retained the use of the long sleeves which dominate the female dancing tomb figurines. Even some of the themes of the early plays have continued to be essential for countless later operas, such as filial piety and other themes related to the feudal, ethical codes.

As has already been mentioned, speculation about how the early plays were actually performed is based on textual and visual sources. No archaic theatrical forms exist anymore in China, where the communist regime consistently destroyed forms of culture that were regarded as feudalistic. If one would like to get an idea of the early Chinese forms of performance, one should, perhaps, turn to the neighbouring cultures of Korea and Japan, which have preserved traditions from early periods when they had close contacts with imperial China and were profoundly influenced by it.