Earliest Sources

Dong Son Gongs: Earliest Visual Sources

Before the period of direct Chinese influence, North Vietnam was the home of a Bronze Age culture called Dong Son. The best-known artefacts created in this culture are large bronze “kettle drums” or gongs, in which dancers and processional performances are also depicted. Together with some cave paintings they give the earliest existing information about the theatrical arts in Southeast Asia.

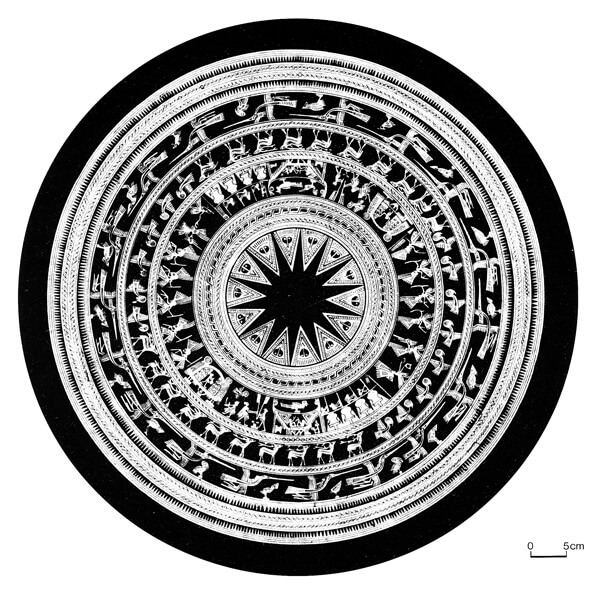

- Tympanum of a Dong Son Bronze drum, c. 500 BC–100 AD Dong Son Drums in Vietnam 1999

The Dong Son culture derives its name from the village Dong Son in northern Vietnam, which was first excavated in the 1920s. It is now generally thought that it was not the actual political centre of the culture, but merely one of the Dong Son principalities loosely linked to each other. The centre of the Dong Son culture was the central region of the Red River basin.

Working with bronze was practised in Vietnam probably from the second millennium BC onward and it reached its technical and artistic peak around 500 BC–100 AD. Among the Dong Son bronze objects, such as tools, vessels, ornaments, weapons, arrowheads etc. the most impressive group is that of the large, decorated gongs, or “drums” or “kettle drums” as they are often called.

The earliest examples were cast in one piece. Later, when gong manufacturing spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, as far as Bali, the gongs were also cast in two pieces, utilising the so-called lost wax method. The basic design of Dong Son gongs consists of a flat tympanum and sides that narrow in the middle.

There has been much speculation about the function of these gongs. It is now thought that they were connected with both ritual and rank, with many found buried in the graves of high-ranking individuals. The materials with which they were made and the skills needed to manufacture them were such that only the wealthy would have been able to own them.

The tympana of the gongs are decorated with a rich variety of motifs, some impressed into the wax through the use of moulds before the bronze was cast and some carved on the wax by hand. The motifs include the central star or sun, which has been identified by Vietnamese scholars as the Solar Star, the central axis of Dong Son cosmology. Comb-teeth motifs, concentric circles and birds surround it. Human figures are also depicted, as well as extremely informative portrayals of everyday life, agricultural scenes, rituals and handsome warships with feathered warriors.

Dancers are often portrayed within the middle section of the tympanum decorations. They are shown in line formations in identical, energetic poses. In their hands they hold different kinds of weapons such as spears, sticks and axes. The dancers wear extremely large feathered headdresses and their lower bodies are covered with long, skirt-like costumes. Similar kinds of dances are still performed in some remote areas in Southeast Asia.

Two Cultural Sources, China and India

Even early archaeological finds show Chinese influence, which spread to the original territory of the Vietnamese in Tonkin and northern Annam at least two centuries before the present era. By 40 BC, these regions were incorporated into the Chinese Empire, to which they belonged for the following nine centuries.

In other parts of Southeast Asia, religions, the language of the court, mythology, law, and art were all adopted from India. The Vietnamese, on the other hand, received the cornerstones of their culture from China, viz. Confucianism, Taoism, Chinese Buddhism, the language of the ruling class, the Chinese classics, the civil service examination system, and their whole model of administration.

Indian influences, prominent elsewhere in Southeast Asia, were adopted via the Indianised kingdom of Champa, which was conquered by the Vietnamese around the fifteenth century. With increasing Chinese domination, however, Indianised elements were to remain marginal in later Vietnamese culture.

Champa and its Dance Images

The kingdom of Champa, or as was most often the case, rather a network of Cham principalities, flourished in the coastal regions of present-day Vietnam from the early centuries AD to the second half of the 15th century, after which, much reduced in size, it survived until the middle of the 19th century.

The region of Champa with its river valleys served as an important stop for the maritime trade route system of the “Southern Silk Road” connecting China to Southeast Asia, India and further to the Mediterranean world. The principal Cham sites, with traces of brick-built temple towers, are scattered around the coastal regions and partly on the plateaus of the interior.

Champa’s history was overshadowed by wars, victorious as well as disastrous, especially with the Khmer. It was finally swept from the political scene by the Sinocised Vietnamese in the 15th century. The legacy of Champa’s arts includes brick temples, fully round sculptures both in stone and bronze, high reliefs, bas-reliefs, ceramics and embossed metal works.

The predominant religion of Champa was Hinduism in its Shivaistic form, which developed in Champa in its own way. Vishnuism played a minor role, whereas Buddhism in its Tantric Mahayana form was popular for a period from the 9th to the 11th century, during which time Chinese influence can be recognized in some of the religious sculptures.

The collection of some 300 sculptures and reliefs in the Museum of Cham Sculpture in Danang, in Central Vietnam, and the much smaller collection at the Musée Guimet in Paris together with those reliefs and sculptures which are still in situ or in minor site museums, form the rather limited core of all Cham sculpture.

- Dancing Shiva, early 10th century, Danang Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

The motifs of the dancing Shiva, found in the tympana reliefs, show a remarkable iconographical variety. These reliefs served as anthropomorphic representations of the main deity of the temple, which was represented on the main altar as the non-anthropomorphic linga standing on its yoni base. The earliest surviving example of the Shiva tympana reliefs is from the 8th century. Their iconography seems to derive from 6th–8th century West India.

- The so-called “Tra Kieu Dancer” from a pedestal, 10th century, Danang Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

Probably the most widely illustrated of all the Cham sculptures is the 10th century “Tra Kieu dancer”. It is a rather well preserved portrayal of a dancer sculptured on a large pedestal. It has been pointed out that this image clearly reflects Indian and Javanese influences.

The pose and the gestures of the Tra Kieu dancer reflect Indian influence. In the dancer’s pose one can, however, recognise one particular element, which is seldom present in Indian or even Javanese dance images. It is the over-bent elbow joint of the left arm, which could easily be seen as the artist’s inability to portray human anatomy. However, it can also be interpreted as the earliest so far known surviving portrayal of the technical and aesthetical characteristic, which was and still is a distinctive feature in classical Javanese and, especially, Thai-Khmer dance techniques.

If the above interpretation is correct, the Tra Kieu dancer reflects, to a certain degree, the localisation process of the Indian-influenced dance tradition in Champa culture. This also applies to another famous pedestal dated to an even earlier period, the 7th century. This pedestal, which once supported a large Shiva linga, shows groups of dancers on the risers of its stairway. The pedestal is otherwise decorated with musicians as well as ascetics in various activities.

- Pedestal with dancers, 7th century, Danang Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

The central figure in the upper panel has turned his muscular back to the viewer while waving a long scarf in his hands as if offering it to the deity. The side figures are in frozen poses and hold offerings in their hands. The poses and gestures of the dancers in the lower panel are clearly Indian-influenced, but what is striking is the dominant role the dance scarves have in these panels. The use of dance scarves is rare in the Indian Natyashastra-related traditions, whereas scarves are depicted in Central Javanese reliefs and they have become an integral element of Javanese dances of later times.

The Cham dance reliefs reflect the localisation process of Indian dance in Southeast Asia. The over-bent elbow of the Tra Kieu dancer and the dominant role of the scarf in some of the Cham dance images are clearly indigenous or are at least Southeast Asian features. However, the Indian influence continued to thrive during the whole of Champa’s golden period as can be seen, for example, in a lintel relief from the 11th century showing female dancers and musicians.

- Dancers and musicians on a lintel, 11th century, Danang Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

The dancers hold their hands above their heads in a salutation mudra while their open legs are in a typical Indian-influenced position. The asymmetry of their pose may be explained by the fact that the reliefs show not the first movement of the salutation, but one of the following movements when the dancers bend their bodies from side to side. These kinds of invocation dances or sequences of dance are still part of the repertory of Indian dances as well as of some Thai ritual dances.

One could conclude that the Indian, especially Southwest Indian, influence is prominent in the Cham dance images, although they are only seldom based on direct Indian models, maybe because the Indian influence could have been, at least partly, received via Indonesian islands.

Vietnam

The Vietnamese have often fought for their independence. The first, short-lived, Vietnamese dynasty was established around the middle of the tenth century, and over the centuries, the Vietnamese gained control of areas in Annam and further south in Cochin-China, the traditional territory of the Khmers.

The division between North and South Vietnam is geographical: the coastal stretch is long and narrow, and civilization concentrated around two river valleys, the Red River in the north and the Mekong in the south. Central Vietnam, however, has a distinct identity as a mountainous region.

Cochin-China was for a long time the European name for the whole of Vietnam, but from the end of the eighteenth century the French used it only in referring to the south. They called the northern parts Tonkin and the centre Annam, although the latter term was sometimes used for the country as a whole. The Vietnamese never used these terms; for them, the south was Nam Bo, the centre Trung Bo, and the north Bac Bo. In rough outline the history of Vietnam can be broadly divided into three cultural periods:

- tenth to fourteenth century: joint influence of Chinese and Indian culture;

- fifteenth to eighteenth century: predominantly Chinese influence; and

- eighteenth to twentieth centuries: a period of Western influence.

Hué, Chinese-influenced Court Culture

Vietnamese history is marked by a continuous struggle against Chinese hegemony and conflicts with other conquering powers, such as the Khmer Empire and the Thais. In 1802 a new state of Vietnam was formed with its capital in Hué, where the court maintained its own Chinese-influenced traditions of art and culture. The court and its customs lived on even after 1857, when French military rule was established. In 1887 the territory of Vietnam that became part of the new French Indo-Chinese Union, which after 1893 included Cambodia and Laos, was ruled by a French governor-general residing in Hanoi.

- Court theatre at the Hué Imperial Palace Jukka O. Miettinen

The court in Hué relinquished the remnants of its former political power after World War II, shortly before Ho Chi Minh declared the founding of the Democratic People’s Republic of Vietnam in September 1945. The tragic war in Vietnam, which began in the 1960s, and its various consequences have left their mark on the country, but much of its traditional, and particularly popular, culture has been preserved to the present day.