The Origins of Asian Theatrical Traditions

In Asia, as in many other regions in the world, the origins of theatre and dance can be traced back to several early, archaic types of performance. In Asia they include

- early religious rituals,

- ancient movements imitating animals, or so-called animal movements,

- the martial arts, and

- the art of storytelling. Later,

- the complex behaviour codes of different periods, the most intricate of them being court etiquette, also left their undeniable marks on theatre and dance.

In fact, most of the so-called “classical” styles of Asian performing arts (formulated roughly from the 13th to the 19th centuries) can be analyzed or deconstructed so that these original “root” traditions can be recognised. In the later “classical” traditions these root traditions are, however, intermingled with each other in surprisingly various ways.

1. Rituals

- The wai kru ceremony in Thailand pays homage to the guru or the master teacher Jukka O. Miettinen

In many cultures the origins of theatrical arts can be traced back to early religious rituals. In ancient Greece, for example, the classical tragedies evolved from earlier, powerful rituals performed in honour of the god Dionysos, and the origins of dance in China are both found in ancient shamanistic performances. In the West, as mentioned above, the connection between theatre, dance and religion was broken after the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.

- A Buddhist procession in Burma Jukka O. Miettinen

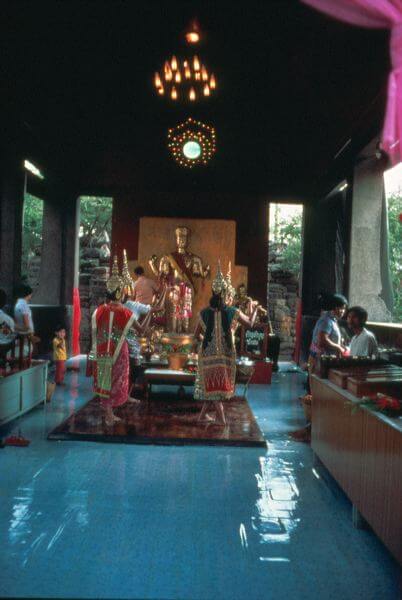

- Dance offering in a Hindu temple in Lopburi, Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

In Asia, particularly in South and Southeast Asia, the bond between religion and theatre and dance is very strong even today. This may be at least partly explained by religious attitudes. In the monotheistic religions that originated in the Near East, Judaism, Islam and Christianity, the human body is regarded as something sinful and thus corporal art forms were banished from their rituals. God may be praised through the visual arts, architecture and even singing, but more physical expressions were more or less prohibited in a religious context.

In most of the Asian religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, such a strict division between the sinful body and “pure” spirituality has not existed and thus the human body has retained its holiness; it has been accepted as a worthy medium to praise even spirits and gods. Many forms of performance, for example temple dances, are, in fact, regarded as offerings, prayers, gaining merit or a kind of spiritual meditation.

- Symbolic hand gestures of Indian dance Sakari Viika

- Symbolic hand gestures of Indian dance Sakari Viika

One example of how theatrical practice evolved from rituals is the mudras or symbolic hand gestures, so crucial to Indian dance and theatre traditions. They developed from the age-old sacred gestures used in religious rituals by the Brahman priests.

An abundance of ceremonial elements can still be found in many of the Asian theatrical traditions simply because most of them stem originally from earlier rituals, and actually a dance or theatre performance itself can, in many cases, still be regarded as a ritual.

Trance Rituals and Shamanism

As a broad generalisation, one could say that the rituals connected with trance elements seem to represent a very early stage of ritual performances. They often seem to precede the present institutionalised religions, such as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism. In many of the Christian and Muslim cultures these early examples of religious expression were forbidden and destroyed. This is not, however, the case in many of the Asian cultures in which later religions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, did not abandon the earlier layers of belief systems but rather assimilated them into their own ideologies and practices.

- Kratoy or transgender person gets ready for a trance ritual in Chiangmai, north Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- The actual trance ritual Jukka O. Miettinen

- End of the ritual Jukka O. Miettinen

Trance indicates a kind of hypnotic or half-conscious state of mind, which can be attained by several means or techniques. They include suggestive, rhythmic music, whirling movements, the control of breathing (hyperventilation) and the use of mind-altering substances such as hallucinogenic drugs.

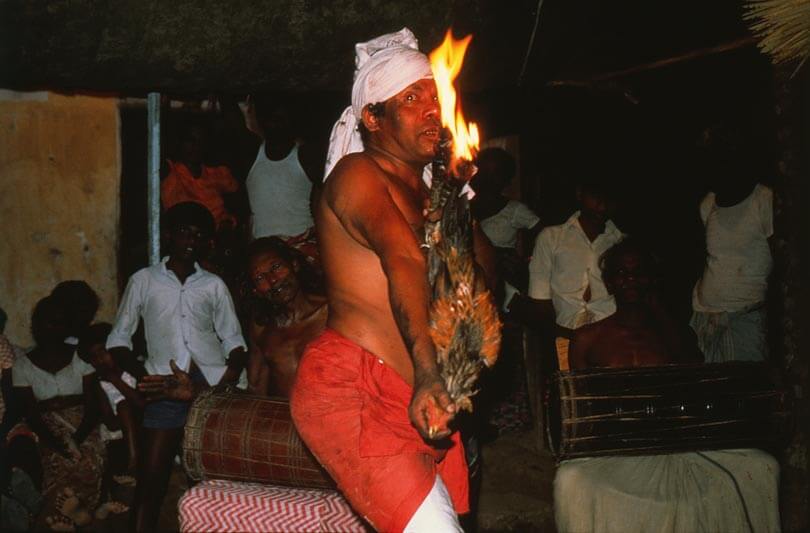

- The patient is killing a cock in a tovil exorcism ritual in Sri Lanka Jukka O. Miettinen

- A shamanistic ritual dance from the southern coast of the Korean Peninsula Jukka O. Miettinen

In this “other” state of mind the performer/performers of the ritual, and sometimes also members of the audience, are able to contact the spirit world. Trance rituals are strongly associated with the early belief system usually called shamanism. The term was earlier related to the so-called Northern Shamanistic Belt, which extended from northern Scandinavia to Siberia, Manchuria, and Korea in the east.

In this form of shamanism the shaman “priest” had various roles. He or she could act

- as a healer, or

- as an oracle, or the shaman could function

- as a mediator between the ancestors or sprits and the community he or she was serving.

This northern form of shamanism has now mainly disappeared with the exception of Korea, where the tradition is still thriving today.

Shamanistic Ritual as a Form of Theatre

Shamanistic rituals often include features which relate them to theatrical performances. During the ceremony the spirit priest often wears clothes which refer to the particular spirit the shaman is getting in touch with. In Nordic countries the shaman often wore animal furs, feathers and horns associated with local sacred animals such as bears, eagles, and deer or elks.

- A nat pwe ritual in Mandalay, Myanmar Jukka O. Miettinen

Sometimes a shaman is transformed into a kind of transsexual being, since it has been believed in many cultures that during the trance a male spirit prefers to manifest himself through a female body and female spirit through a male body. These elements, the transforming of the performer with costuming into a kind of stage character and the transformation, through the trance, into “the other”, relate these rituals to theatrical practices.

There is, however, a crucial difference between a shamanistic ritual and a conventional theatrical performance with its “make-believe” agreement. It is a fact that shamanistic ritual has generally been regarded to be true or genuine, not a kind of fictional stage presentation we are usually familiar in the theatre. These kinds of ritual trance performances have generally been regarded as very important for the spiritual life and well-being of the community in which they are performed. They have offered a channel in which to communicate with sprits and ancestors or to grant, for example, a good harvest etc.

- By employing a special singing technique, the chorus of a kecak performance of Bali goes into trance Jukka O. Miettinen

Trance rituals can be almost uncontrollable in their spontaneity and power. This creates an element of actual danger for the performer and sometimes for the audience as well. It can actually be a question of life and death, as will be seen later in connection with some Indian and Balinese traditions. This, of course, is a crucial difference between an authentic trance ritual and our conception of a theatrical performance.

Trance Rituals in Asia

Above, some of the characteristics of trance rituals were described with a reference to the kind of shamanism as has appeared in the region of the so-called Northern Shamanistic Belt. If shamanism is slightly more widely defined, as it now tends to be, it is possible to find trance traditions with shamanistic features almost everywhere, in Africa, Central and South America and especially in Asia. As has been pointed out, most of this kind of traditions seems to stem from archaic, mostly animistic belief systems preceding the present institutionalised religions. Later, powerful trance-related traditions from India, Korea and several Southeast Asian countries will be described.

Structurally, the trance rituals are not always strictly divided into a possessed spirit priest and his or her passive spectators. Sometimes there is no clear borderline between the executor of the ritual and its observers. One example of this kind of ritual is the famous kris dance in the so-called Calonarang dance drama of Bali.

One of its main protagonists is a horrendous witch, who has the power to make people turn against themselves. The performance reaches its culmination in the self-stabbing dance, where part of the village audience, incited by blind rage, attack the witch. She, however, is able to hypnotize the villagers so that they start to stab themselves with their daggers. This extremely dangerous dance is controlled by the village priests, who bring the dancers back to normal consciousness.

- In the ecstatic kris dance of Bali the dancers stab themselves with daggers Jukka O. Miettinen

This kris dance is not only an example of how the borderline between the performer and audience in a trance performance can melt away; it is also an example of how an ancient trance ritual can be assimilated into a later type of performance since the trance section is absorbed into later story material. As mentioned above, many of the Asian religions assimilated the earlier belief systems and their practices. Similarly, the trance element has been assimilated into later theatrical forms, Calonarang being but only one example of this phenomenon.

As in the kris dance, the element of danger is also strongly present in many other trance performances. One example is a certain tradition of the teyyam tradition from Kerala in southwestern India. There a young man is chosen to perform the ritual, before which he meditates and fasts for a longer period. Before the ritual he is dressed with leaves from the trees and elaborate make-up is painted on his face while his eyes and mouth are covered with a kind of silver mask. Torches are added to his costume and they are set on fire when the performance starts. During the ritual the performer whirls around. If he himself catches fire, it is interpreted as a negative sign. If, however, he does not catch fire, it is seen as a sign that the gods are satisfied. The element of danger is alarmingly concrete!

The Actor in Ritual Performances

The role of an “actor” in ritual performances differs from the role of an actor in mainstream western theatre. In western theatre it is common that the actor uses his or her own personality, memories, expressions and particular physiognomy to create a role. This is not the case in most of the archaic ritual performances. In contrast, the performer often tries to “weep out” his or her personality by, for example, fasting and meditating. The performer is often expected not to act the role of the god, spirit or mythological character, but rather to receive it in order to be able to serve as its embodiment.

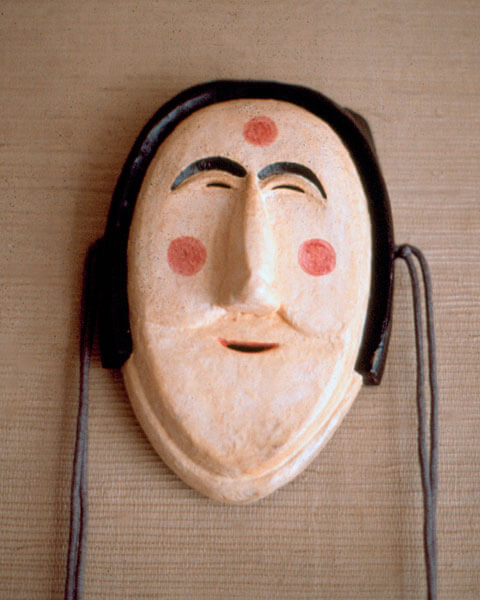

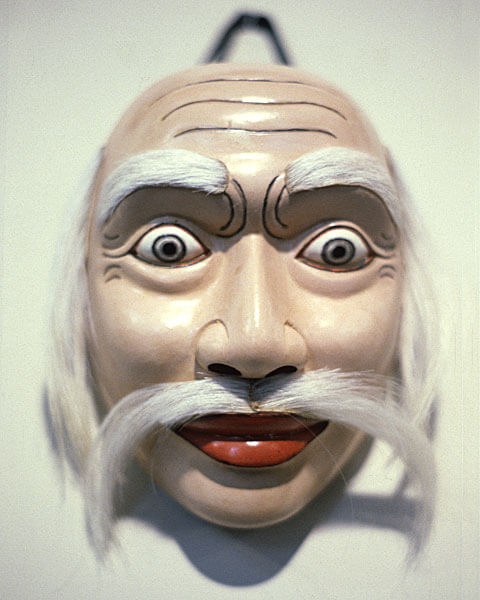

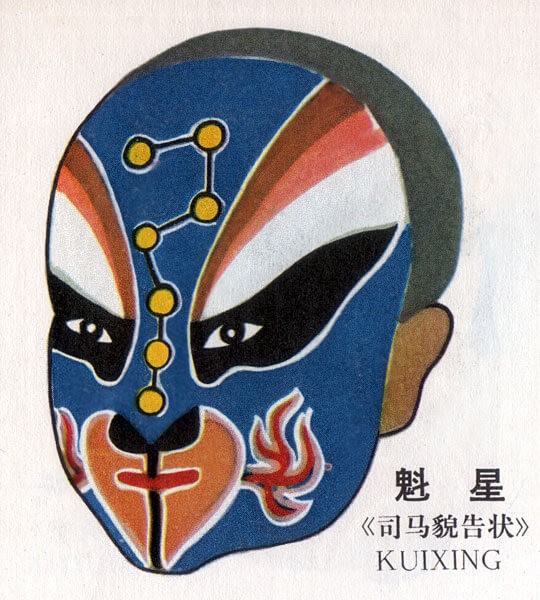

The embodiment of a sacred being or character is also possible by employing fixed costuming, masks or complicated make-up systems. By these devices, the personality of the performer is dispelled and performers are able to embody the sacred being in a similar way, generation after generation. It is probably because so many Asian theatre and dance traditions have their origins in archaic rituals that the conception of acting in many “classical” traditions also still bears similarities to the actor’s role in archaic rituals. Fixed role categories, costuming, masks or make-up keep stage characters alive for centuries and only an actor-dancer with decades of training is able to add something “new” to the interpretation of the role.

- Mask from Korean folk theatre tradition Jukka O. Miettinen

- Khon mask from Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

- Balinese topeng mask Jukka O. Miettinen

- Balinese topeng mask Jukka O. Miettinen

- Chinese opera styles are characterised by stylised facial make-up Jukka O. Miettinen

- A model for Peking opera make-up collection of Veli Rosenberg

- A model for Peking opera make-up collection of Veli Rosenberg

- An Indian kathakali make-up for a noble male character Jukka O. Miettinen

- A mask of young man in noh theatre, Japan Sakari Viika

- A sanni mask from Sri Lanka, Colombo Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

2. Animal Movements

- The Monkey King is the beloved anarchist from many Chinese operas Sakari Viika

The tradition of imitating the movements of animals seems to stem from the earliest periods of known human existence, that is the times when humans were hunter-gatherers and their entire livelihood depended on the natural world and the animals around them. Indeed, the earliest known artefact showing a man imitating an animal has been found in a Stone Age cave in France and is dated to approximately 15 000 BC.

It depicts a man clothed in animal fur and wearing the horns of a deer; his pose clearly imitates the movements of a deer. Man was a hunter during the early Stone Age. Thus it is no wonder that the majority of Stone Age cave paintings depict animals. Their function has been widely speculated about and most experts seem to agree that they had a magical function. By identifying himself with the being of an animal the hunter probably wanted to create a kind of magical bond with the animal his life depended on.

- Many of the basic positions of nora dance-drama of southern Thailand are based on imitation of birds’ movements Jukka O. Miettinen

- Krishna performing peacock’s dance in a raslila performance in northern India Paula Tuovinen

There may also have been a more practical reason for the imitation. With his primitive weaponry it was very important for the hunter to get close to animals. Once the hunter was able to imitate their movements, it was possible to get nearer the animals, without frightening them. Thus there may be several reasons why early man imitated the movements of animals. Dance anthropological studies have pointed out that these animal movements may, in fact, represent the origin of human dance.

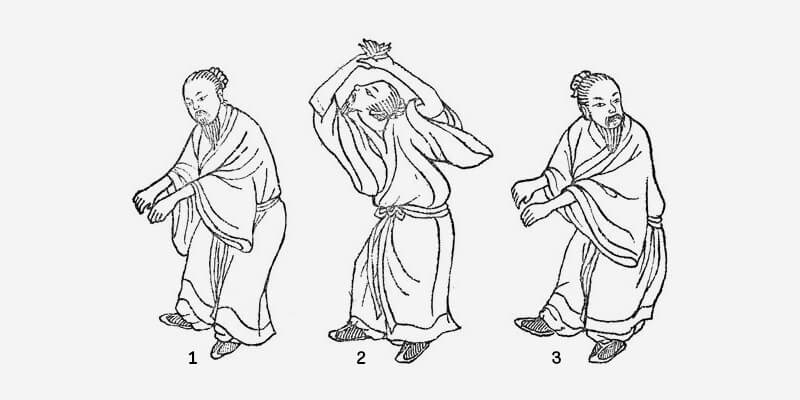

Animal movements still form today an integral part of the training series of different martial art techniques, as will be discussed below. Also, hundreds of dance traditions around the world involve animal movements. Which animals were or are imitated naturally depends on the fauna of each geographical region. As mentioned already, in the sphere of Nordic shamanism, the animals imitated were the bear, the eagle and the deer or the elk.

- Dance of the half-bird-half-human kinnaris from Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

Animal movements in Asia have often been based on the movements of, for example, monkeys, snakes, elephants, and peacocks and other birds, real or mythological. The popularity of animal movements is not limited only to archaic traditions. Even the charm of the most popular of all western classical ballets, Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, is based on the fact that in its great “white scenes” the movements of the ballerinas aim to capture the essence of a swan’s being.

3. Martial Arts

- Silat martial arts from Malaysia combines dance, animal movements and stylised combat movements Jukka O. Miettinen

As has already been pointed out, most of the Asian theatrical traditions are performed by stylised, dance-like movements. Many of these intricate movement techniques have developed during many centuries, even millennia. They include several different elements, such as symbolic hand gestures, fixed ways of standing and sitting, sculpture-like poses and defined ways of portraying, for example, a battle.

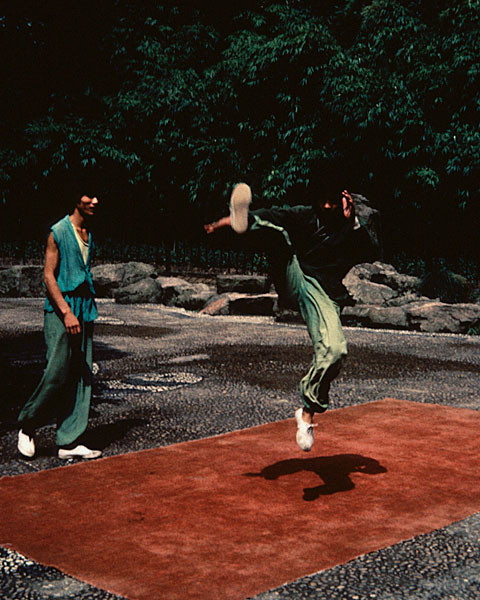

- Wushu or martial arts training in China Jukka O. Miettinen

- Wushu or martial arts training in China Jukka O. Miettinen

Many movements, particularly those related to fighting, can be traced back to ancient martial arts and weapon worship. Most of the Asian cultures have their own sophisticated martial art systems also known now in the West, such as the Chinese taiji (t’ai chi), the kalaripayattu and thangta of India, Thai boxing, the silat of the Malay world and the Japanese kendo and judo etc. Many of these martial systems have a very long history. For example, the Chinese tradition can be traced back to periods before the present era.

From Animal Movements to Martial Arts

- A historical woodblock print showing three of the many animal movements of Chinese wushu martial arts: 1. Deer, 2. Bird, 3. Tiger.

The existence of so many animal movements in the present martial art systems is a clear indicator of the long history of martial arts. It is possible that the ancient animal movements of prehistoric periods formed a kind of basis on which the martial systems were later developed. Thus it is often through the martial arts that animal movements also found their way into theatrical traditions.

- Training of kalaripayattu martial arts in Kerala, India Sakari Viika

Basically, the martial arts traditions can be divided into four groups: (1) those rehearsed with weaponry, (2) those executed without weaponry and, furthermore, (3) those rehearsed in groups or by couples, and (4) those rehearsed alone, as a kind of solo form. The weapons vary in different traditions. They usually include traditional weaponry such as spears, sticks, swords, daggers etc.

The original function of the martial arts was, no doubt, to practise the skills of combat and self-defence. The arrival of firearms, of course, reduced their original function and many of them developed into kinds of psychophysical training methods that focused on mental and physical skills, self-discipline and mental harmony. These kinds of meditative and magical aspects may have been present in many of the martial arts traditions even at a very early stage.

- The fighting scenes of Peking opera are constructed from well-rehearsed acrobatic units Jukka O. Miettinen

From Martial arts to Dance and Theatre

Most of the Asian martial arts techniques have clear ritualistic features and they share movements and poses, such as the open-leg position, with the dance traditions of the regions where they evolved. Martial arts techniques have influenced Asian dance and theatre traditions deeply. In fact, when martial arts are isolated from their original function, fighting and/or self-defence, and are shown either as a part of a theatre or dance performance or as independent martial arts demonstrations or performances, they bear similarities to dance performances, although martial arts as such are rarely regarded in Asia as a form of art.

- Purulia chhau dance theatre from East India Sakari Viika

- Seraikela chhau dance theatre from Bihar, East India Sakari Viika

- Combat scene from Mayurbhanj chhau from Orissa, India Sakari Viika

- A variant of the sacred baris gede, a form of ancient war dance of Bali Theatre Arts Monthly 1936, Rose Covarrubias

One could simplify the process of how the martial arts became part of the theatrical arts as follows. Firstly, they were adopted as rituals, such as, for example, the Balinese war dance baris, which was originally performed before the warriors went to war. Secondly, they were adopted into classical traditions because the performers (for example members of the court and its body guard) had the basic knowledge of them. Later, when grand court theatre forms evolved, including also great battle scenes, the martial arts provided an already established movement vocabulary that was already familiar for both the performers and the audience.

- A battle scene from Peking opera Jukka O. Miettinen

As will been seen, many of the Asian classical traditions include martial arts techniques even today. The well-known grand-scale examples include the kathakali of India, the khon of Thailand, and the kabuki of Japan. Probably the best known example in the West is the Chinese Peking opera in which the spectacular fighting scenes are constructed of carefully rehearsed units based on a similar training system as the actual martial arts. In fact, a Peking opera actor studies these skills from the beginning of his or her training and continues to develop these skills further if he or she is specialising in many of the Peking opera’s martial role types.

4. The Art of Storytelling

Video clip: Pansori performance of Song of Heungbo Veli Rosenberg

- Pansori storytelling tradition from Korea Jukka O. Miettinen

So far mainly the physical aspects of the origins of Asian theatre traditions have been discussed, such as the trance rituals, animal movements and martial arts. If we consider the textual and narrative aspects of Asian theatre, it is obvious that the origins can be traced back to the simple act of conveying a story to the audience orally. This kind of storytelling traditions can still be found in abundance in Asia today, for example in the Islamic world of West Asia, in China, in Korea etc.

- Current storytelling tradition from Tianjin, China Veli Rosenberg

- Current storytelling tradition from Tianjin, China Veli Rosenberg

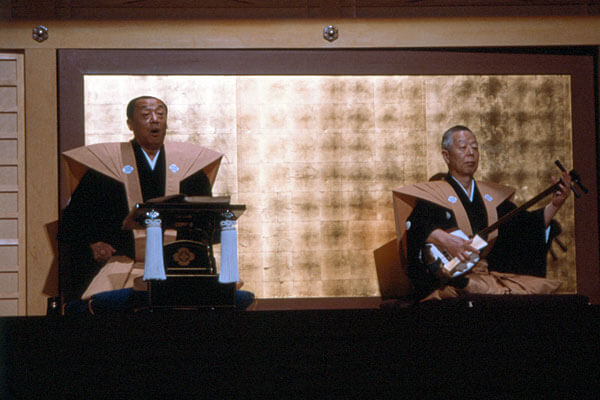

- Bunraku puppet theatre performed at the Bunraku-za theatre in Osaka, Japan. The dialogue is delivered by a storyteller who sits with the musician at one side of the stage Jukka O. Miettinen

Many of the later theatrical traditions, such as shadow theatre, puppet theatre and many of dance theatre forms evolved from early storytelling traditions. Indeed, in Asia, as will be seen later, the storytelling tradition served, at least partly, as the starting point from which the complex theatrical performances, based on the same oral and later written material, developed.

- In the Japanese noh theatre the commenting chorus sits on the right side of the stage Jukka O. Miettinen

The process could roughly be outlined as follows: (i) the starting point is the act of storytelling, i.e. the act of conveying the oral literary tradition. (ii) Gradually the storytellers started to employ different kinds of visual devices to illustrate their narration (panels, scroll paintings, shadow figures, puppets and in some cases even dolls), and (iii) storytelling was enriched by gesticulation, body movements, mime, dance, music etc. During this process the act of storytelling became more theatrical in character and the narrative tradition and performing arts cross-fertilised each other, which resulted in many of the present classical theatrical forms.

Just to give some examples: the wayang wong dance drama of Java is believed to have developed from the Javanese wayang kulit shadow theatre in which the primus motor of the whole genre is a dalag puppeteer, who is also the storyteller in the performance. Sometimes during the history of the process live actors came to replace the puppets. The background to the khon mask theatre of Thailand seems to be a similar case: in this the narrators take care of the storyline and dialogue while the actor-dancers gesticulate according to the narration. The Japanese bunraku puppet theatre, for example, developed when the puppeteers in the 17th century started to co-operate with the so-called joruri storytellers, who still dominate the whole art form with their expressive recitation.

5. The Etiquette and the Formulation of the Present “Classical” Traditions

- A formal court scene from khon dance-theatre of Thailand Jukka O. Miettinen

The term “classical” is a dangerous one, because it is so value-laden. Thus “classical” art forms can easily seem to represent something more valuable or “high” than the “non-classical” folk or popular forms. In this connection classical forms generally refer to traditions which evolved from court traditions and which were added during the beginning of the 20th century to the curriculum of state art schools and universities. These traditions are now usually classified as “classical” dance in their respective countries. Besides those traditions, hundreds of “smaller” traditions live in Asia, which can be just as sophisticated and intricate as those classified as classical ones.

- Court ritual performed in the 1920s at imperial court in Hué, Central Vietnam.

As mentioned above, one could generalise that the present classical forms in Asian theatre developed roughly between the 13th and early 20th centuries. As their background lies mostly in the court traditions, they understandably reflect the behavioural codes from the courtly milieu in which they were shaped.

One important feature of mainland Southeast Asian culture has been the conception of the god-king. This cult created an extremely intricate court etiquette, which was also reflected in dance and dance theatre. As the performances often featured the gods to which the living king was related, it was natural that the physical surroundings and the modes of behaviour of the artistic presentations followed the models set by the king’s actual court. Thus many dance theatre forms of the court, especially those on a grand scale, still reflect today the behavioural practices and etiquette of courts from centuries ago.

- Japanese formal bugaku court dances performed in front of a temple Embassy of Japan

- Burmese court dress from 19th century; Theatre dresses often imitate court costumes from earlier times, Yangon National Museum, Myanmar Jukka O. Miettinen

This is not only an Asian speciality. For example the 17th and 18th century opera seria or “serious opera” reflected the etiquette of contemporaneous courts in its rhetoric gestures and elaborate bows and curtseys. Similarly the Baroque dance was shaped and controlled in the 17th century French court by King Louis XIV himself. When the Baroque dance later evolved into Romantic ballet in the early 19th century many of the originally courtly practices were still retained as kinds of references to bygone days.

Similarly in Asia, many of the conventions, such as ways of standing, sitting, kneeling, crouching, gesticulating, saluting etc. which could now be easily be interpreted as being purely stylised theatrical conventions, can, in fact, be traced back to actual historical behavioural practices and codes.