The Twentieth Century

Western influence began to be felt in Japanese cultural life during the Meiji period (1868–1911), when the Japanese Empire was transformed, through the so-called Meiji Restorations, into an industrialised world power. Many aspects of Japanese society, its infrastructure, army and laws were remodelled according to Western models.

The long-lasting rule of the shogunate was demolished and Emperor Meiji (who ruled 1867–1912) became the actual ruler. The old Shinto religion was reinterpreted so that it emphasised the divine origin of the imperial house and thus the emperor became the head of the Shinto cult.

The Fate and Trends of Traditional Theatre during the Meiji Period

In Japan’s rapid process of opening itself up to the outside, particularly Western, world, everything Western became highly fashionable. This also led to drastic changes in the fields of theatre and dance.

Noh and kyogen were regarded as odd and old-fashioned, although noh was protected and supported by the imperial court. It also maintained even older forms, such as kagura shrine dances and bugaku court dances. Bunraku puppetry mainly flourished in Osaka.

Kabuki, on the other hand, did not lose its popularity. However, even it was influenced by Western stage realism, as can be seen in the “new kabuki” or shin kabuki plays of the period in which stage realism was favoured and kabuki’s many special features and stage tricks were eliminated.

Japanese intellectuals quickly familiarised themselves with Western dramatic literature, which partly influenced the new trends in kabuki too. A reform group was founded, which established a Western-influenced administration system for kabuki.

Kabuki actresses, who were unheard of in kabuki’s history since 17th century, were trained, although this reform was doomed to be short-lived. Patriotic themes were adapted for the kabuki stage, which led again to a new sub-genre of kabuki, katsureki geki or “plays of contemporary history”.

In these new forms of kabuki it was the Western-influenced stage realism that dominated. One of the reformists of the period was the prolific playwright Kawatake Mokuami (1816–1893), who wrote some fifty kabuki plays. Most of them represent various traditional categories of kabuki, but he also wrote so-called zangirimono plays or sewamono plays set in the Meiji period. He also translated Western dramas into Japanese.

International Winds of Change

At the stormy beginning of the 20th century, the new forms of theatre were used as a platform for patriotism and political reforms. One of the important men in theatrical life at that time was Kawakami Otojiro (1864–911), who, with his wife, a famous actress, established his own theatre company, the Kawakami Company.

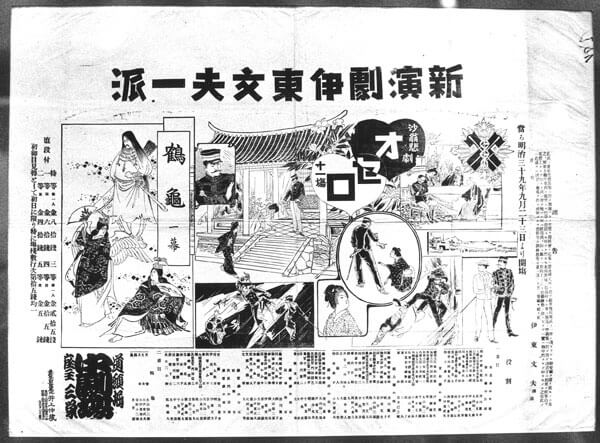

- A poster of a Japanese production of Shakespeare’s Othello, 1906 Tsubouchi Memorial Museum, Waseda University

Otojiro’s style was based on kabuki with a Western flavour. For a while he studied in Paris. After returning to Japan, he wrote plays with both political and patriotic undertones. Otojiro’s troupe toured America and Europe with great success and influenced the trends of European theatre and dance during the period of great interest in things Japanese, often called Japonisme (From East to West, from West to East – Controversies in Cultural Exchanges).

Japan’s influence was also felt in its neighbouring countries. The Western type of spoken theatre found its way to Korea and China via Japan. Many Korean intellectuals studied there during the Japanese occupation in the early 20th century. Contacts between the countries remained close even after the occupation.

The Chinese tradition of spoken theatre (huaju) was also initiated in Japan. A Chinese student group, called The Spring Willow Society, staged the first act of La Dame aux Camélias in Tokyo in 1907. This new form of theatre soon spread to China, particularly to international Shanghai.

One form of the fusion of Japanese and Western theatre was represented by the shimpa plays of the Meiji period, which, in a way, antagonized the stylized, baroque kabuki. The realistic shimpa plays focused on various problems of contemporary Japan; actresses also appeared on the stage.

Growing interest in Western drama led to the establishment of the Literary Society in 1906. Its leading figure was the scholar, dramatis and translator Tsubouci Shoya. Some amateur actors who had links with the Literary Society staged excerpts from Western plays for the first time in Japan. This novelty was called shingeki or “new plays”. This was also the beginning of Japan’s Shakespearean tradition, which still continues today.

A group called The Free Theatre was founded in 1909. It consisted of experienced kabuki actors who were interested in Western drama. More works by Western dramatists were translated and staged, such as plays by Ibsen, Wilde etc. However, tightening censorship before and during World War II seriously restricted freedom of expression.

After World War II

As elsewhere in the world, in Japan, too, the new media, the movie industry and TV, have dominated the world of entertainment since World War II. However, in Japan a serious revival of the traditional performing arts also began. So the future of noh, kyogen, bunraku, and kabuki seem secure. Many new trends seem to prevail, particularly in the field of kabuki, from the flashy “Super Kabuki”, with its new tricks and technologies, to serious attempts to study kabuki’s past.

Several Japanese writers began to work in the field of spoken theatre. In the West, the best-known is Yuokio Mishima (1925–1970). He wrote, among other dramas, a collection of modern noh plays in which he captured the spirit of noh in a completely new way. Among other important writers are Kobo Abe (1924–1993) and the “father” of Japanese absurd drama, Minoru Betsuyaku (1937– ).

The theatre scene in the Japan of today, with its various genres such as the traditional forms, the spoken theatre, experimental forms, musicals, Western opera and ballet etc. is so overwhelmingly rich and varied that it is simply impossible to form an overall view of it.

There are, however, some 20th-century forms of performing arts, which grew from or comment on the Japanese traditional forms of theatre and dance. They include the all-female Takarazuka Revue as well as modern butoh dance, which has also had its impact on the contemporary dance scene in the West.

The Takarazuka Revue

One of the specialties of Japanese 20th century theatre is the famous Takarazuka Revue. Its headquarters is in the city of Takarazuka, near Osaka. There is both the Takarazuka Grand Theatre and the Takarazuka Music School, in which all of its present 400 actresses have been trained under strict, almost military discipline.

- One of the male impersonator stars of the Takarazuka Theatre of the 1980s Takarazuka Theatre

The specialty of the Takarazuka Revue is that all the actresses are young, almost teenage girls. They also perform the male roles. This was a sensational novelty when the institution was founded in 1913. It was the brainchild of Kyobashi Ichizo, who founded a railway line to the city of Takarazuka. To attract passengers he also founded a hot-spring resort as well as an all-girl revue in the city of Takarazuka.

All of Japan’s classical forms of theatre are strictly male-dominated. Takarazuka turned the roles upside down when young, attractive girls with low voices appeared in the male roles. In this sense, the Takarazuka tradition can be compared with the Chinese yue opera, which evolved in the Shanghai region at the same time. Since the 1920s both forms have attracted huge, mainly female audiences.

The originally rather modest Takarazuka Singing Troupe has grown in a century into a huge institution with over 400 actresses and some 1000 staff members. The Takarazuka Revue Troupe is currently divided into five troupes.

They give performances on the two stages in Takarazuka, and also at the Takarazuka Theatre in Tokyo and often tour the United States and Europe. Altogether, the Takarazuka troupes give some one thousand performances to about two million spectators annually.

The repertoire consists of two basic types of performances: revues and full-night musicals, especially written and composed for Takarazuka. Some of the plays are adapted from Western movies, some from popular Japanese comics. Plays derived from Western literature have also been popular, and so have Western musicals.

As all the plays are highly romantic love stories it is natural that the Takarazuka style is both sugary-mellow and highly melodramatic. The dance technique is based on Western show dancing. In its semi-historical costuming and colourful stage sets the Takarazuka style has a highly romantic, fairytale-like character.