Manipuri Dances, the Isolated Dance Tradition of Northeastern India

Just like the southern state of Kerala, the tiny northeastern state of Manipur also has its own rich theatrical tradition, which preserves both archaic and animistic, as well as later “classical”, forms. While most of Kerala’s genres are firmly related to the classical (margi) Natyashastra-related tradition, the dance-orientated forms of Manipur have evolved in isolation and have retained their unique style and spirit to this day.

The valley state of Manipur lies amidst the hills of the easternmost part of India, bordering Nagaland in the north, Assam in the west and Myanmar (Burma) in the east. Thus, in fact, it belongs to the Southeast-Asian cultural sphere, which is also reflected in its dance traditions.

The people of the Manipur valley are called Meities (also Meeteis) and they trace their antiquity back to Vedic times. The indigenous, animistic belief system, Sanamahi, is very much a living tradition still today, although the Krishna bhakti form of Hinduism was adopted in Manipur as a state religion in the 15th century.

In Manipur the ancient belief system and the culture it created are interwoven with Hinduism. This is clearly reflected in the rich dance tradition in which Hindu themes are performed in a uniquely indigenous style, while at the same time some dances are still related directly to the Sanamahi religion and its rituals and ceremonies.

Manipur also has its own tradition of martial arts, thangta. It includes exercises without weapons and exercises with weapons, as well as solo and group exercises. It probably has a very long history, as is indicated by its aspects related to the archaic weapon worship. The basic choreography of the exercises repeats the form of an 8, as do the body and hand movements too. This is also the most characteristic feature of all Manipuri dances.

The History

The earliest written evidence of Manipuri dances is a copper-plate inscription from the 2nd century AD crediting a certain king with introducing drums and cymbals into Manipuri dances. They are still the main instruments used for accompaniment.

The arrival of Krishna bhakti in Manipur in the 15th century provided new functions and themes for dance. The classical bhakti poetry became the main textual sources for Manipuri bhakti-related dance-dramas, called raslilas.

- Raslilas, like other Manipuri dances, are characterised by soft, spiral-like movements Jukka O. Miettinen

It was probably in the 18th century that the dance-dramas related to Hinduism, the raslilas, got their present form. This is indicated by the fact that Maharaja Bhagyachandra (who ruled in 1759–1798) composed three of the five types of raslilas. He also designed the peculiar barrel-like dance costume, characteristic of the raslila tradition still today. The Manipuri dance manual, the Govindasangeet Lila Vilasa, is also attributed to him. In the 19th century two other Maharajas further expanded the repertoire.

Manipuri dances became nationally known after the Bengali philosopher, poet and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Rabindranath Tagore, saw Manipuri dances in 1919 and became a great admirer of them. He invited an important teacher-guru to teach them at Santiniketan, his own university.

Later, Manipuri dances were admitted to the list discussed above of the “classical” Indian dance traditions, although they, in fact, have very little in common with the other margi-style classical dance forms. Now they are widely taught and performed throughout India, and many interesting modern adaptations of the style have been made and are still being made at the moment.

The Technique

The Manipuri dance technique is characterised by a soft and graceful quality of movement. As already mentioned in connection with the local martial arts technique, thangta, both the floor patterns and the body movements tend to repeat the shape of an 8. The movements are round, having a kind of endless, flowing, and spiral-like quality.

Some aspects of the dances seem to reflect the influence of the Natyashastra-related tradition. They include the expressions of the rasa sentiments, mostly those of love and longing, as often in the bhakti-related dance forms. Some of the standing positions, too, seem to correspond to the Natyshastra’s codifications.

In many respects the Manipuri dance technique, however, seems to be unique to India; it is more closely related to northern Southeast Asian traditions than to those of the Indian subcontinent. The Manipuri repertoire concentrates on group choreographies, which are relatively rare in other Indian classical dance forms. Furthermore, Manipuri dancers do not wear ankle bells, which form an important element of almost all other dance forms in India.

In the Manipuri technique there are no sharp deflections of the body, so characteristic of southern Indian dances. The dancers move in a serpentine gait with corresponding movements of the body, the arms, and the hands. The female style aims at closed, low positions in which the feet never rise above the knee level, whereas in the masculine style the movements aim more upwards, and even energetic, acrobatic jumps and leaps may be employed.

The Repertoire

The repertoire of the Manipuri dances may be divided roughly into two categories, those related to the indigenous pre-Hindu belief system and those related to the Krishna bhakti themes. These categories, however, overlap, since even the bhakti-related dances are performed in the indigenous style.

Possibly one of the most archaic forms of Manipuri dances is the maibi dance, which was originally performed during the Laiharoba festival, related to the indigenous Sanamani religion. As with most of the Manipuri dances, maibi is also a group dance, in this case originally performed by spirit priestesses. Its choreography reflects the ancient cosmological concepts of the Meitei people.

- Drum dance Sakari Viika

- Cymbal dance Sakari Viika

- Cymbal dance Sakari Viika

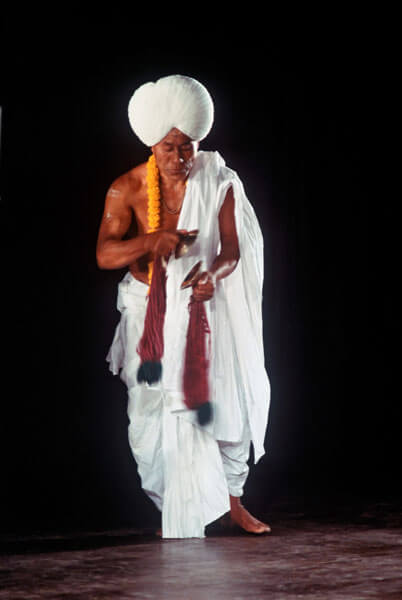

Several of the male group dances, such as pung cholam (drum dance), nupa pala and karta cholam (cymbal dances) have a deeply hypnotic quality. They usually start softly and slowly while the tempo gradually increases. The cyclic, serpent-like movements are repeated while the performers play their instruments at the same time. The dances, performed by male performers in snow-white loincloths and often with ball-shaped, white turbans, combine movement and sound in a unique way.

Khamba thoibi is exceptionally a duo dance with a narrative content. It portrays a love affair between a prince and princess of warring clans. The instruments accompanying most Manipuri dances include a pung drum, cymbals, and some wind instruments, most often a flute.

Raslilas

- Raslilas most often depict events from Krishna’s amorous youth Jukka O. Miettinen

The Krishna-related dance-dramas of Manipur are called raslilas (ras, sometimes also raas means dance; lila, play) or simply ras dances. They are large compositions, most often performed by a group of female dancers, although all-male troupes, dancing in female disguise, also exist.

Like the raslilas of the Delhi region, which have been discussed above in the sections dealing with forms of pilgrimage theatre, Manipur raslilas are also the result of the widespread Krishna bhakti cult, which reached Manipur in the 15th century.

- Radha and Krishna Jukka O. Miettinen

All the plays illustrate episodes from Krishna’s life, mainly the miracles and loves of his childhood and youth. There are five raslilas focusing on the Radha-Krishna theme and several others illustrating various episodes of Krishna’s life. Many of the main raslilas have been composed by Maharajas of Manipur. Other poems are also used, including the works of important bhakti poets, such as Jayadeva, Vidyapati, and Chandidas.

The dance-dramas, dominated by group formations, also include several duos and solo dances. All the female characters, that is, Radha and gopi cowherd girls, dance in the graceful lasya style, while Krishna, also played by a female dancer, employs a more energetic and playful tandava style.

Traditionally raslilas have been performed in a specific enclosure in front of a temple. No backdrops or other stagecraft are used. The dance is dominated by peculiar costuming, which is said to have been designed by Maharaja Bhagyachandra in the 18th century. A legend says that he saw the ras dance of the gopis in a dream and that the present dance costumes were designed according to his vision.

- A dancer disappears inside her barrel-like skirt Jukka O. Miettinen

The costume for the female roles is dominated by a large barrel-like skirt, which with its floating movements emphasises the dancers’ whirling. There is an unexpected sequence of movements in which the whirling dancers suddenly bend down and almost disappear inside their stiff skirts.

The female dancers’ heads are covered with short, glittering veils. The dancer who plays the role of Krishna wears a more simple costume with a blouse and a wrapped dhoti-like lower garment. On her head she wears Krishna’s obligatory peacock feather crown.

- Krishna is covered by coloured powder during the holi festival Jukka O. Miettinen

The glittering costumes with their deep greens, yellows, and reds, and the seemingly endless repetition and elaboration of the soft curves of the Manipuri technique give raslilas a dreamlike quality. It easily coaxes the spectators into experiencing the gentleness and warmth of bhakti art.

The whole group of Manipuri ritual singing, drumming and dance traditions were included in UNESCO list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013.