Noh, Crystallised Aesthetics

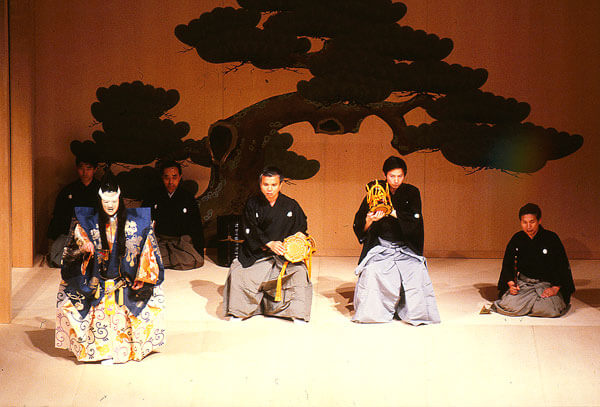

Video clip: A scene from the play Hagoromo, “The Feather Mantel”, which falls into the category of Wig Plays. Its shite represents a heavenly maiden who descends to earth. To get back her wings, or the feather mantle, she performs a heavenly dance Veli Rosenberg

Noh (no) is regarded as one of the great classical traditions of world theatre. Its wooden stage structure, its extremely slow and measured acting technique, grandiose costuming, beautiful masks, and minimalistic music have all been preserved more or less in the same form as they were perfected in the Muromachi period (1333–1568).

- Noh, which is always performed on a wooden stage structure, combines stylised acting, chanting, dance, and music Jukka O. Miettinen

- Noh masks are valued works of art Sakari Viika

Noh plays are known for their strength and other-worldly poetic beauty. They are admired around the world and many of them have been translated into several languages. Noh evolved in the refined court circles in Kyoto and in the upper echelons of the samurai class. Thus it is no wonder that Noh created sophisticated aesthetic theories, which one of its originators, the actor and playwright Zeami, formulated in his treatises.

In fact, noh plays form only a part of a still more complex theatrical tradition, that of nohkagu. It combines the serious noh dramas with lighter kyogen farces. Traditionally a full, whole-day performance included five noh plays, interspersed by four kyogen farces. In this text noh and kyogen are discussed in separate chapters.

The History

The actor and playwright Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami (1363–1443) are regarded as the inventors of noh. The new art form was not, however, created from the void. Several other forms of entertainment were popular during the time when noh gradually got its shape.

Among the early forms of theatre were sarugaku plays, which combined dance, music and mimetic acting. This rather light form of entertainment, which possibly originated in China, became the basis on which Kan’ami and Zeami then shaped their austere novelty, noh.

Another root tradition for noh was dengkaku, a versatile genre of entertainment that had its roots in rice-planting songs as well as in ancient fertility rites and spirit possession. It gradually evolved into popular forms, which blended music, singing, dancing, and mime.

When the shogun’s court was moved to Kyoto, Kan’ami founded his school there. It was named after his stage name, Kanze. There he started to refine the melodies of sarugaku and the energetic rhythms of dengkaku. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shogun of the period, became an admirer of noh. This heralded the long tradition of noh’s patronage by the uppermost samurai class.

Zeami, Kan’ami’s son, was only twelve years old when he performed for the shogun for the first time. The shogun took Zeami under his protection and they became close friends. Thus Zeami was raised to the highest level of the social hierarchy.

Without any doubt, Zeami is the most remarkable individual in the whole history of noh. First of all, he was regarded as the topmost actor of his time. Furthermore, he was a very productive playwright and, besides that, he was also a choreographer, musician, and stage director.

Zeami also formulated the sophisticated theory of noh in his treatises, which will be discussed later. After the death of Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, Zeami’s popularity at court declined. When he was an old man he was finally exiled to a remote island, where he is believed to have died.

New noh schools evolved to cultivate noh in its classical form, perfected by Zeami. Noh was amalgamated with kyogen farces, and the new combination was called nohgaku. Remarkable playwrights enriched noh’s repertoire and the patronage of the samurai class continued while even some of the shoguns themselves appeared on the Noh stage.

During the Edo period (1608–1868) noh also continued to be the art of the samurai class, although in the new cultural climate some commoners also became its patrons. Gradually noh also came to be known outside the noble samurai circles, for example, in the form of temple performances.

The old feudal world crumbled at the beginning of the Meiji period (1868–1912) and Noh lost its original patronage. Noh was not regarded as fashionable amid the new, western-influenced forms of entertainment. However, owing to the support of the imperial family, noh did not completely die out.

Continuation of the tradition was secured in 1881 when the Noh Society was founded. Noh has now also gained new popularity, particularly among educated audiences, both in Japan and in the West. It was officially added together with kyogen theatre to UNESCO list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008.

Actors and their Roles

Traditionally all noh actors have been men. (Recently a few actresses have also appeared on the noh stage). The actors of a certain play are categorised, not according to the character or character type they are embodying, but according to the role or importance of the character in the structure of the play.

Thus the actors are categorised as

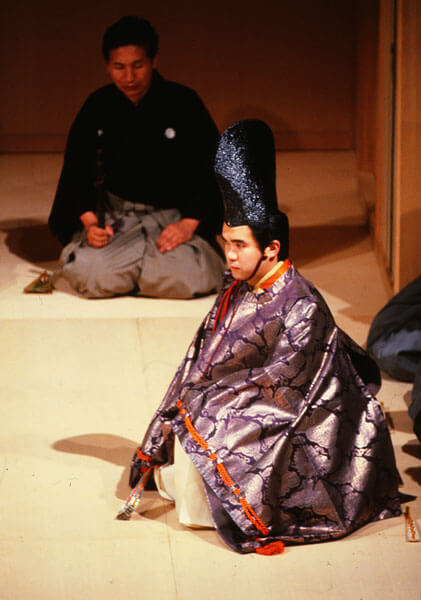

- A masked shite actor in the role of a heavenly maiden in the play Hagoromo Jukka O. Miettinen

- Waki or supporting actors always represent ordinary human beings and they do not wear masks Jukka O. Miettinen

- Shite or the principal character, who often appears masked;

- Waki or the supporting role, who is always an unmasked human being;

- Shite-zure actors perform the roles of shite’s companions;

- Waki-zure actors represent waki’s companions;

- Kokata, or child roles, are performed by boy actors.

This system does not mean that an actor specialises in one of the above categories. In fact, an actor can appear in any of the role types (except kokata). Besides that, he can also sing in the chorus, which forms an integral element of a noh performance.

Types of Plays

There exist 240 noh plays. They are categorised according to their shite, or main characters.

- A scene from the play Hagoromo, The Feather Mantel, which falls into the category of Wig Plays. Its shite represents a heavenly maiden who descends to earth. To get back her wings, or the feather mantle, she performs a heavenly dance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Mask of a female demon Jukka O. Miettinen

- God Plays (Waki Noh)

These plays narrate stories about various gods or god-like beings. The shite actor usually wears a mask. At the beginning he often appears in disguise and reveals his identity only at the end of the play. - Warrior Plays (Shura Mono)

The shite actor plays the role of a samurai or another warrior, who, after his death, has not found peace for his soul. Only after prayers from outsiders are his karmic deeds forgiven, and he is able to find final peace. - Wig Plays (Katsura Mono)

In these lyrical plays the shite actor mostly plays a woman’s roles (read the synopsis of Hagoromo, one of the wig plays). - Miscellaneous Plays (Zatsu Mono)

This group includes various plays which do not fit in the other categories, such as scripts dealing with ghosts or mad persons. - Closing Plays (Kiri No)

The shite actor usually plays a demon role in these energetic plays.

In their structure the plays follow a certain aesthetic principle, called jo-ha-kyu. It was derived from old court music with its roots in India. Jo refers to the beginning or introduction, and its tempo is slow. Ha refers to the middle part in which the actual dramatic situation is presented. In kyu, or the final part, the tempo of the action and the music quicken and the drama finally reaches its climax.

In the introductory part of a play the waki and shite (often in disguise) appear separately and ceremoniously introduce themselves. Thus the ingredients of the drama are made clear. In the middle section the tempo of the performance becomes faster and the drama often climaxes in a stylised dance (mai) in which the shite recalls the past. In the finale, the shite returns to the stage and the dramatic action leads to its majestic end.

The structure of a full-day noh performance should follow the jo-ha-kyu principle in a similar way, too. The opening play often represents the category of the “god plays”. The plays of the middle part of the performance represent the “warrior” or “wig plays”, while a play belonging to the category of “closing plays” ends the performance.

The Contents and the Language

Although there are some more recent noh plays, most of them deal with the ethical dilemmas of the samurai class of the period when the plays were written. A basic conflict is created by the two completely opposite ideologies of the period, i.e. the pacifistic Zen Buddhism and the strict code of ethics of the members of the samurai class, who were trained warriors.

Very often the plays contemplate on karmic questions, based on the Buddhist world-view, for example, on how a person must pay for his bad deeds before being liberated from being a ghost between this and the other world (read the synopsis of Tenko, one of the plays dealing with the liberation of a wronged soul).

- Tenko, based on a Chinese legend, tells about a boy who received a magic drum from heaven. To get it the emperor lets him be killed. Nobody, however, can get a sound out of the drum. A prayer ritual is arranged for the boy’s soul, which then appears. It is dancing; it beats the drum and finally disappears into heaven Jukka O. Miettinen

A noh play may be based on a short episode picked up from classical literature, such as the Genji Monogatari, discussed above (read the synopsis of Lady Aoi). Many of the themes are adapted from the great epics of the feudal period, such as The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari) and the Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari). Anthologies of classical poetry also supplied themes for the plays.

Thus the plays are full of references to classical poetry, Buddhist scripts, historical anecdotes, and even Chinese poetry. One characteristic of noh’s language is that there is rarely a sharp distinction between poetry and prose.

To understand the noh texts in all their depth required the highest education in feudal Japan. As the plays were intended for the samurai elite and the court circles, the period’s highly formal etiquette and courteous way of speaking are also reflected in the language. A simple question (“What is your name?”, for example) requires seven words to be politely asked in a noh play.

It is no wonder that only a very few members of modern audiences completely understand the texts and their complicated language. That is why most spectators today take with them a kind of guide booklet, in which the symbolism and the literary allusions are explained.

Music and the Chorus

- The musicians sit at the rear of the stage, in front of the “mirror wall”, which is decorated with a painting of a pine tree Jukka O. Miettinen

- The chorus sits on the right, facing the stage. It describes the action, landscape etc. and often sings the lines of the stage characters Jukka O. Miettinen

As mentioned above, the music of noh was refined from older musical traditions. Music in noh does not “accompany” the action as is often the case in Western forms of music theatre. In noh, music forms an aural level of its own, which rarely, and mainly only in the climaxes, exactly matches the action on the stage.

A small orchestra and a chorus accompany or, maybe more correctly, give their aural addition to the performances. The musicians and the chorus singers are collectively called hayashi kata. The musicians sit at the rear of the stage facing the audience, while the chorus sits to the right of the audience facing the stage and the action.

The instruments include a flute as the melodic instrument and three kinds of drums, the number of which may vary according to the requirements of the play. The notated music, like the structure of the play, follows the jo-ha-kyu principle discussed above. The music’s silent moments are emphasised, which creates an aural impression of space.

- The shouts of the drummers accentuate the tempo and underline the stage actions Jukka O. Miettinen

The flute produces long melodic lines, which often seem to disappear into distance. Sharp drumbeats accentuate the time and build up the intensity and climaxes of the drama. The drummers also use their voices. They shout and howl, which fills the empty space between the beats. These calls, called kakegoe, have an important role in anticipating and underlining the dramatic action.

The wooden stage also functions as a kind of instrument. The “mirror wall” behind the orchestra serves as an acoustic surface, which reflects the music towards the audience. In the climatic dance sequences the stage is used as a kind of drum when the actor loudly stamps the resonating wooden floor. The stamping sound is amplified by large pots hidden underneath the floor of the stage.

Singing is done both by actors and the chorus. In fact, the lines of a character can be divided so that an actor sings part of it and the chorus the other part of it. In the noh songs, originally derived from ancient Buddhist chanting, the voice is kept very low, regardless of whether the character is male or female.

The vocal technique may sound, at the beginning, monotonic. In fact, the sung parts are performed with five different colourings. Roughly translated, they are the strong, the gentle, the dynamic, the longing, and the sad modes.

The Acting Technique

The acting technique of noh is characterised by its slowness and measured precision. All the elements unnecessary for the drama are eliminated. This gives noh its crystalline, almost hypnotic quality.

In the noh standing position the body, with a straight back, leans slightly forward while the chin is pointed towards the throat. The arms curve slightly forward while the hands are kept in a fixed closed position in which the fingers are motionless.

- In the noh standing position, the otherwise straight back of the actor is bent slightly forward from the waist Jukka O. Miettinen

- In noh walking, the feet, covered with white socks, slide on the floor Jukka O. Miettinen

- The dance sequences culminate in powerful stamping steps Jukka O. Miettinen

- The final dance of Tenko Jukka O. Miettinen

The stylised, sliding noh walking is called hakobi. The soles of the feet, covered with white socks, are rarely lifted from the floor. The knees, hidden by the heavy costuming, are kept slightly bent, which enables the actor to slide on the stage floor without any visible vertical movements. Male characters have a slightly open standing position, while female characters keep their feet closer.

The slightly bent positions of the knees and the back make it possible for the actor, in a way, to “grow” on the stage. During a dramatic moment, for example in connection with a fateful revelation, the actor may straighten up, creating a stunning impression of growing in size.

The dance sequences of noh, called mai, form the climactic highlights of many of the plays. The noh dances are extremely minimalistic in their movements. The dance sections are very archaic in character, limited to a few circling movements, changes in the sculpturesque body positions, and some hand movements. The dance finally culminates in powerful stamping steps.

The Masks

- Those actors who do not wear masks keep their faces completely expressionless Jukka O. Miettinen

The extremely measured and minimalistic noh acting technique, which has been discussed above, seems partly to stem from the strict court etiquette of the periods when noh theatre was shaped. According to the etiquette, facial expressions were regarded as vulgar. So too in noh, those actors who do not wear masks keep their faces completely expressionless.

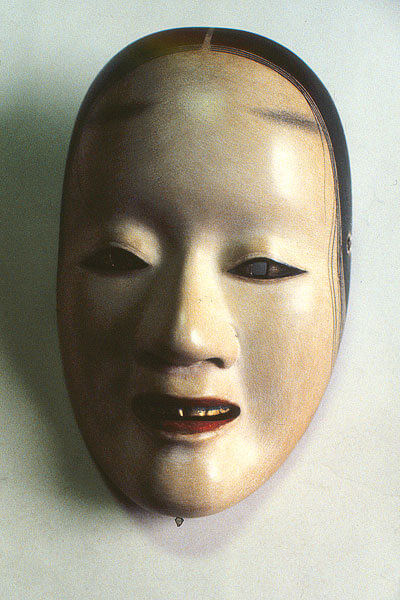

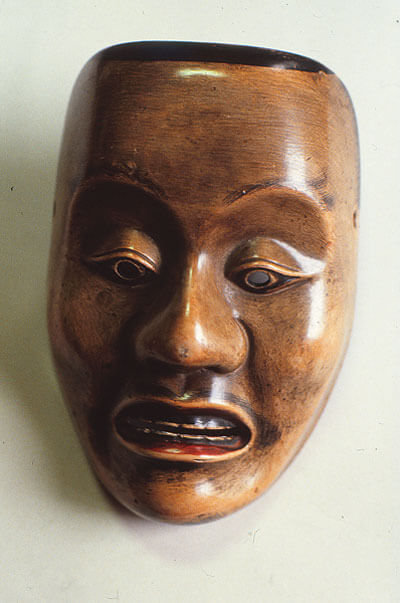

- The expressions of the masks reflect ambiguity, which enables their expression to change when they are seen from different angles Sakari Viika

However, the measured movements may be partly due to the use of masks. By slightly altering the angle of his head, the actor is able to change the mask’s expression. When the angle of the mask is adjusted, its expression seems to change from happiness to sorrow etc. This is possible because the expression of most of the masks reflects a certain neutral ambiguity, which allows the audience to make several interpretations.

- Mask of a middle-aged woman Jukka O. Miettinen

- Mask of a samurai Jukka O. Miettinen

- Mask of a blinded samurai Jukka O. Miettinen

The noh masks were developed from earlier Japanese mask systems. Compared, for example, with the wooden gigaku masks, the Noh masks are smaller, as they cover only the central part of the actors’ faces. Old noh masks are regarded as valuable works of art. They have been preserved and used by generations of noh families and their schools.

Masks are worn by several of the shite characters, as well as some of the sure companion characters. Most of the masks are character masks, for example those of a young woman, an old woman, a middle-aged samurai, a young aristocrat etc. However, some of the masks are reserved for particular roles.

- Small cushions are attached to the back of the masks so that they are at the right angle on the actors’ faces Jukka O. Miettinen

Before going onto the stage, the actor adjusts the mask on his face in the adjoining “mirror room”, where he then contemplates the role he is going to perform. Small cushions fastened to the back of the mask ensure that the basic angle of the masks will be correct, regardless of the physiognomic differences in the actors’ facial features.

The Costuming

- Hagoromo’s colourful brocade robe Sakari Viika

The gorgeous costuming of noh follows the practices of the court circles of the Muromachi period. It is believed that in the very early stages of noh’s history the costumes were simpler. Just like the masks, the sophisticated brocade robes of the noh costumes are also regarded as valued works of art.

The costumes (shozoku) are full of symbolism, and the guide booklets, which many of the spectators use to follow the performances, often include explanations of the meanings of the costumes and their ornamented details.

- During the performances stage assistants help to ensure that the position of the wig and the costuming is perfect Jukka O. Miettinen

There are some specific forms of costumes characteristic of noh. They include, among other things, the very wide, folding trousers of some of the male characters and the highly ornamented colourful robes of many of the female characters.

With his wig and complicated costume a noh actor is almost like a living sculpture. Thus the perfect order of the draperies and the hair are of upmost importance. That is why stage assistants appear every now and then on the stage to straighten the wig and the costume.

The Stage and the Props

- The earliest existing noh stage from the 18th century is in the courtyard of a Zen monastery Jukka O. Miettinen

- Modern noh stages are erected in indoor theatre halls [JOM]

Only in a few forms of Asian theatre does the stage structure form such an integral element of the whole art form as is the case in noh theatre. The oldest existing noh stages are outdoor structures, built some three hundred years ago in the courtyards of Zen monasteries. Nowadays the stage structures follow exactly the same model, although they are now most often erected in indoor halls.

- The slow crossing of the hashigagri walkway symbolises either a long journey or travelling from the other world to this world or vice versa Jukka O. Miettinen

The stage itself is a wooden platform of some six meters square. The stage has an extension for the chorus on the right side of the audience, and at the rear an extension for the musicians. On the left there is a bridge or a walkway (hasigagari), which connects the stage with the backstage area. Immediately after the bridge there is the so-called “mirror room”, in which the actors adjust the masks on their faces. The “mirror room” is separated from the walkway by a small colourful curtain.

Behind the stage, facing the audience, is a wooden wall, always decorated with a large painting of a twisted pine tree. The wall reflects the music towards the audience, while the painted pine tree and painted bamboos on the side walls remind one of the time when noh was performed outdoors.

An elegant reference to Zen Buddhist aesthetics and garden planning is given by the narrow strips of white gravel with miniature pine trees in front of the stage. In a similar way the stage’s unpainted wooden structure with its high roof also reflects the spirit of Zen architecture. The colour of the wood varies from a natural shade to a reddish colour and further to dark patina. The shades give each stage its particular atmosphere.

- A pine tree, fastened in a white framework, is brought to the stage by a stage assistant Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from the play Tsuchigumo, in which an evil spider demon throws a net over a warrior Jukka O. Miettinen

- Special stage effects are employed in some of the noh plays Jukka O. Miettinen

Props are used sparsely. The most important prop the actor handles is a large fan. Larger stage props are, indeed, conceptual in character. If, for example, a pine tree is needed, the stage assistants bring to the stage a white framework to which a pine tree is attached. This basic framework may also serve as a carriage, a tower, a boat etc.

Aesthetic Theories of Noh

Besides noh dramas, Zeami, the great exponent of noh, also wrote acting treatises. Originally they were secret writings for the members of his noh school, but they most probably also circulated among the patrons of noh, that is, among the members of the upper samurai class and thus shaped the general aesthetics of the period.

The treatises, which became generally known only at the beginning of the 20th century, give unique inside information about the religious-philosophical aspects of noh and serve today as an extremely valuable source for students of Japanese aesthetics. Zeami’s treatises include, among other things, Fushikaden or the “Transmission of Style and the Flower”, Kadensho or the “Communication of Flower Acting”, and Shikado or “The Path to the Flower”.

Zeami regards noh as The Way. Thus noh, in a similar way as meditation or Zen Buddhist calligraphy and ink painting, can serve as a vehicle for a sudden “realisation”, which opens up the path to nirvana. Furthermore, he regarded noh performances as prayers for peace and prosperity.

According to Zeami, noh is a combination of three elements:

- role-play or imitation,

- poetic chanting, and

- music.

Zeami also discusses the term hana or flower. It has several meanings, for example, the highest artistic achievement, the mysterious radiation of art etc. An actor must reach hana, although it varies according to his age. According to Zeami, hana can only be experienced when there are secrets; without them there is no hana.

In order to reach hana the actor must work constantly through his whole life. In acting there must be, according to Zeami, “bone”, “flesh” and “skin”. By bone he means natural talent, flesh refers to learned skill, while skin means the impression of easiness, which finally creates beauty.

The Five Schools

Noh is still performed today and taught mainly by five “schools” or actor lineages, which were founded over the centuries by important individual actors. The schools are the Kanze, Hosho, Konparu, Kongo and Kita Schools. The most prestigious of them is the Kanze School, as it was founded by Kan’ami, the first exponent of the whole art form.

Usually all the professional noh performers belong to one of the five schools. As the profession is, to a great extent, still a hereditary profession, the artist’s role in the noh tradition depends on his family relationship within the actors’ lineage.

Normally a performer joins the same school as his father, who thus trains the next generation. Within a noh school the highest authority belongs to the head of the family, who directs and advises other members of the family/school throughout their careers. Thus noh forms a well-guarded, closed world of its own. Outsiders may, though, practise and even perform some of its aspects, such as noh songs and dances.