Sanskrit Dramas

India also has an old and long-lasting tradition of full-length poetic plays, which are called Sanskrit Dramas because they were written mainly in Sanskrit. In fact, however, they combine both classical Sanskrit with Prakrit or different forms of vernacular languages.

The tradition was maintained for nearly 1 200 years, which makes it the longest continuous performing tradition of any drama texts in the world. The tradition of performing Greek tragedies, for example, lasted only about half a millennium, while the continuous performing tradition of Shakespearean dramas lasted less than a century.

The earliest Sanskrit plays were written in the early centuries AD and they gradually ceased to be performed at some time during the 15th century, when Sanskrit was no longer a living, spoken language, and the Muslims had invaded northern India, where the tradition had been thriving.

Playwrights and their Works

As has already been mentioned, the earliest Sanskrit dramas date from the early centuries AD. The problem, however, with this genre is that the plays are almost impossible to date accurately. This also means that very little is known about the lives of their authors. The use of the Sanskrit language of the learned upper castes indicates that most of the Sanskrit dramas represent court theatre, which was probably created and performed under royal patronage.

The Sanskrit dramas cover a wide range of subjects and types of play. They include full-length poetic love stories, political plays and palace intrigues, as well as shorter farces and one-act love monologues. The foremost drama genre centred on the character of a noble hero. These “heroic dramas”, often with plots derived from tradition, are called natakas. Another important type of drama is a kind of social play dealing with various kinds of human relationships. These plays, mostly invented by their authors, are called prakranas.

The earliest existing plays are attributed to Bhasa. The best known is a kind of political romance called The Vision of Vasavadatta. Other writers include the poet-king Sudraka, to whom three plays are attributed. The most famous of them is The Little Clay Cart, in which a love story and political intrigue intermingle.

Ratnavali is a complicated intrigue set in harem by the poet Harsha, while Bhavabhuti is known for his Ramayana-derived play, The Latter Story of Rama, and a love story, Malati and Madhava. The Minister’s Seal, the only existing complete play by Visakhadatta, with its ruthless political plot, is a kind of thriller of its time. The most famous of all Sanskrit playwrights, both in India and in the West, is, however, Kalidasa.

Kalidasa

As is the case with most of the Sanskrit dramatists, very little is known about the life of Kalidasa, the most celebrated poet in the history of India. It is believed that he belonged to the priestly Brahman caste and that he lived in North India at some time during the late 4th to mid 5th centuries AD, that is, during the classical Gupta Period.

His known works include three lengthy narrative poems, and three plays: Malavika and Agnimitra, Urvasi Won by Valour, and the famous Shakuntala (also The Recognition of Shakuntala). Kalidasa’s poetry has been praised for its beauty and “limpidity” or a kind of transparency. It has been seen as reflecting the “ease and largeness of vision”, characteristics of the mature classical Gupta period.

Shakuntala

The Recognition of Shakuntala, or more often just Shakuntala, is regarded as the epitome of Sanskrit dramas. The basic story of this lyric, fairytale-like play in seven acts is derived from the Mahabharata. It was certainly common practice to borrow and enhance elaborate characters and events from the epic literature.

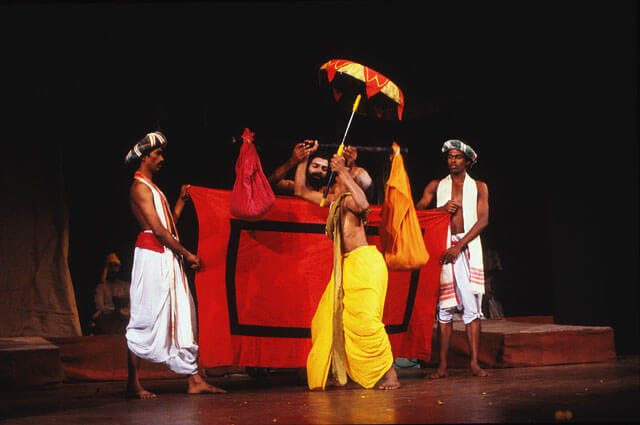

Video clip: King Dusyanta and his charioteer are out hunting; the opening scene of Shakuntala in the kutiyattam style Veli Rosenberg

Shakuntala tells about the love of King Dusyanta and a beautiful girl, Shakuntala, who is the foster daughter of a forest hermit (and, in fact, of semi-divine origin). They meet, make love, and engage in a secret marriage. As a token of his love, the king gives Shakuntala a ring. However, owing to a magic trick, the king forgets Shakuntala, and she is taken to the heavens, where she gives birth to the king’s son. Only when the king sees the ring he has given to the girl does he again remember their love. While visiting the heavens, the king meets Shakuntala and their son and they are finally reunited (synopsis of the play Shakuntala).

The play moves freely from the deep forest to the urban palace and from the earth to different levels of the heavens. Supernatural powers are at play, heavenly nymphs take part in the action, and the king is able to overthrow demons while flying with his airborne chariot.

This fantastic and complex world is described with poetic brilliance and concentrates on the themes of longing and rejection, while the main rasa of the play is love. On a deeper level the conflict is created by the opposing forces of desire (kama) and duty (dharma). Desire versus duty was the standard conflict in many of the Sanskrit dramas, as it has, indeed, been in many Western and Chinese dramas too.

The Languages

The language of Shakuntala, as well as other Sanskrit dramas, is characterised by the blending of classical Sanskrit with local Prakrit languages. The royal heroes and Brahman priests, ascetics and high officials use Sanskrit, while women, children and all low-caste characters speak Prakrit. Thus the plays, already at the level of language, reflect the social and gender hierarchies of their time. This intermingling of languages may also have been intended to make the plays understandable for those spectators who did not understand Sanskrit.

Another characteristic of the dramas is the blending of prose and verse. The verses are mainly in Sanskrit, although, for example, nine of Shakuntala’s 194 verses are in Prakrit. The alternation of languages as well as prose and verse widens the scale of linguistic expression from “high” to “low”, from noble to vulgar, and anything in between.

The Types of Character

The characters of the Sanskrit dramas are types rather than individuals. The main types of character include the noble hero, nayaka, often a prince or a king, and the heroine, nayika. The villain of the play is called pratinayaka.

The clown or jester character is called vidushaka. Surprisingly, he may even be a highborn Brahman. Although he is possibly intelligent, he is usually lazy, while his humour is spiced with eroticism. Because of his social background he is able to move freely in the social hierarchy. Thus he can be a close friend or a personal servant of the hero. However, only he is allowed to add social and even political criticism to the play and he translates the hero’s Sanskrit lines into vernacular language.

The troupes included various professionals, from minor actors to make-up assistants, stage technicians, musicians and the conductor of the orchestra. Music had a central role in the Sanskrit dramas, but it is not known what exactly the genre of music that accompanied the plays was.

The primus motor of a troupe, as well as the actual play, is sutradhara, or the theatre director. He was supposed to have expert knowledge of all aspects of theatre. He also took an active role in the actual performance by introducing the actors and the play to the audience, in the prologue, and often guiding and commenting upon the flow of the story.

Sanskrit Drama on the Stage

- A reconstruction of a wooden theatre house according to the instructions of the Natyashastra, Chennai Jukka O. Miettinen

One of the main questions in recent studies of the Sanskrit dramas is how they were staged and performed. There seems to be a consensus that the acting technique corresponded to the stylised natya, described in the Drama Manual or the Natyashastra, as has already been discussed above. Thus the rasa or the sentiment was conveyed not only by word but also through facial expressions, symbolic gestures and other stylised body language.

It is possible, however, that different types of dramas employed different acting styles. For example, a heroic nataka play may have required a classical, Natyashastra-derived acting style, while a short farce may have been performed in a more realistic style etc.

- An attempt to reconstruct a Sanskrit farce in the 1980s Sakari Viika

It is believed that the theatre houses in which the Sanskrit dramas were performed were rather small because abhinaya, or the mimetic acting style, with its facial expressions and eye movements had to be seen close-up. It is also believed that the stage was bare, and just as on the stage of Shakespeare’s dramas, movements, gestures, and dialogue signalled the locations of actions.

Many of the Sanskrit dramas include stage directions, which seem to support the above hypothesis. They also indicate that some stage props may have been used. They may have included various weapons, chariots etc, although it is also possible that these could have been indicated by movements and symbolic hand gestures.

Sanskrit Dramas in the East and the West

Of all Sanskrit dramas it is Kalidasa’s Shakuntala that is best known outside India. A Shakuntala manuscript was found in a monastery in coastal China, indicating close cultural ties between China and India. It is even possible that the Sanskrit dramas influenced the development of Chinese theatre during the times when the contacts were most active.

Shakuntala was probably the first Asian drama translated into Western languages. It is also one of the very first Sanskrit works ever translated into English. The first translation was done by the famous orientalist, Sir William Jones, in 1789. Its publication was a sensation and it went into five editions during two decades. It was translated into German in 1791, and into French in 1803. Later it was translated into several other Western languages.

One of Shakuntala’s greatest admirers was Goethe, who was inspired by it while writing his Faust. He wrote a poem in praise of Shakuntala:

Wouldst thou the young year’s blossoms and the fruits of its decline,

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted, fed,

Wouldst thou the earth and heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name thee, O Shakuntala, and all at once is said.

(Translation by E. B. Eastwick)

Shakuntala became a kind of icon of the 19th century orientalistic movement. It inspired operas and ballets, among them Marius Petipa’s ballet La Bayadère. But most often Shakuntala’s story was very loosely referred to. It served merely as a source for various kinds of Eastern fantasies.

Shakuntala is probably the most frequently performed Asian play in the West. One of the most important 20th century interpretations was by the Polish theatre guru, Grotowski. Sanskrit dramas and their acting technique are now actively studied both in the East and in the West.