The Song Dynasty (960–1279)

Chinese Opera is taking Shape

After the Tang dynasty the empire split into several smaller states. A new cultural renaissance took place from c. 1000 onwards when the Song dynasty rose to power. At the beginning of the dynasty the capital was Kaifeng in the middle regions of the country, some 500 kilometres to the east of the earlier Tang capital, Changan. Later, because of enemy attacks, a new capital, Hangzhou (Hang-chou), was founded in the south-eastern coastal area. The period was politically unstable. However, many kinds of art, such as ceramics, painting, calligraphy and poetry, attained their classical forms.

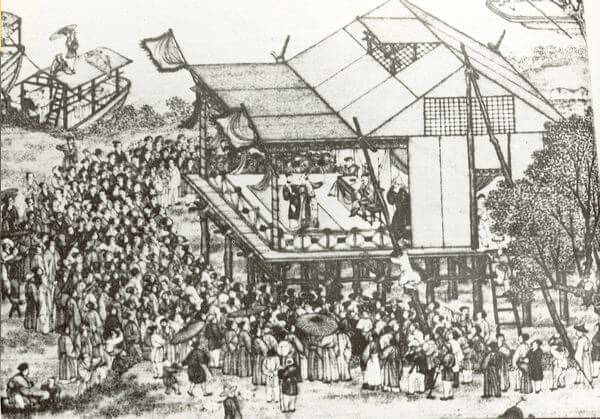

- Chinese theatre has been often performed on temporary stages. This famous painting is from the Song dynasty (960–1126).

Theatres and Teahouses

Many of the Tang period theatrical traditions were continued. Most of the information we have from the Tang period focused on the court practices. From the Song period, however, much information is available concerning public performances. Maybe because of the impoverished court, the entertainers were obliged to find their audiences from among the growing merchant and handicraft population. In both Song period capitals, in northern Kaifeng and in southern Hangzhou, there were large entertainment or “red light” districts (wazi, wa-tzû) offering any kinds of amusements. In the theatre houses and in the teahouses it was possible to see mimes, dance spectacles, acrobatics, circuses with animals, and magic shows. Prostitutes lured customers by singing and dancing, and the alleys were lined with fortune-tellers and street musicians.

- All over in the Chinese world the New Year celebrations include the Lion Dance that has a history of hundreds of years. This dance is performed in Taipei, Taiwan. Jukka O. Miettinen

The popular repertory included several dances reflecting the traditions of foreign cultures and earlier times. They encompassed powerful male dances related to the martial arts, popular drum dances, and numbers imitating animals, such as butterflies and peacocks. Dancing lions appeared on the streets during festivals. Ordinary people enjoyed the shows of yangge (yang-ke) village music groups. Their performances featured familiar stock characters such as monks, young scholars and sturdy villagers. Female dancers added their gracefulness to these shows, which were, more or less, improvised kinds of commedia dell’arte.

Continuation of the Court Tradition

At court the performing traditions inherited from the Tang court were continued, although on a reduced scale. Adjutant plays were still popular and the most spectacular dance performances could almost evoke those of the Tang period and the smaller-scale performances gave pleasure even to connoisseurs. The process of merging together different forms of performing arts intensified further and resulted in theatrical genres, which had already many of the distinguishing features of later Chinese opera.

Zaju, an early Form of Opera

During the Song period, a new form of theatre was born. It was zaju (tsa-chü), which combined drama, music and dance. It gradually evolved into two forms, the southern and the northern. The northern one, characterised by its string accompaniment, continued to be performed for a longer period. A performance started with a music and dance “prelude”, after which the actual dramatic action followed. It combined acting, speech, declamation and singing. The show ended with a comic number and instrumental music.

No complete Song zaju scripts exist today, although it is known that there once were hundreds of them. Some of them were, however, assimilated into some of the later theatre forms. Certain stock characters of zaju had their roots in the clowns of the earlier adjutant plays, but the gallery of characters expanded further. Instead of two characters, several actors performed on stage. The male lead was called moni, and a kind of narrator or the primus motor of the play was called yinzi (yin-tzü). An actor who could play officials and female roles was called zhuanggu (chuang-ku). The characters derived from earlier adjutant plays were the clowns with painted faces, fujing (fu-ching) and fumo (fu-mo).

The stories covered a wide range and featured ghosts or heroes and villains of ancient times, who made their dramatic entrance onto the stage in their elaborate costumes. Love stories were also popular. Many of the plots were loosely based on earlier story material, such as religious or historical legends, and stories about the supernatural. The plots often involved a young scholar who was forced to leave for the capital to attend the imperial examination. Young lovers are separated and they have to go through many hardships and adventures – a basic theme for countless later operas.

- A scene from a 13th century play, Top Graduate Zhang Xie, showing a selfish scholar and a beauty in distress. The character types of later Chinese opera can be already recognised although the costuming is more modest than, for example, in the later Peking.

Nanxi, the early Southern Opera

In 1125 the northern Song capital, Kaifeng, was conquered and the Emperor was captured. Part of the court fled to the south, where a new capital, Hangzhou, was founded in 1138. The southern regions had their own local drama form, called nanxi (nan-shi), which combined indigenous dialect and melodies with mime and dance numbers. Nanxi was popular in southern parts of China from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Some twenty nanxi scripts exist today and almost three hundred titles of plays are known. The stories were more or less similar to those of the northern zaju plays. The play started with a spoken introduction while the number of acts varied.

The Earliest Existing Complete Play Script

- A scene from a 13th century play, Top Graduate Zhang Xie, showing a selfish scholar and a beauty in distress. The character types of later Chinese opera can be already recognised although the costuming is more modest than, for example, in the later Peking.

Top Graduate Zhang Xie, Zhang Xie zhuangyuan (Chang Hsieh chuang-yüan) is so far the earliest known complete Chinese play script (synopsis). It represents the nanxi style and it was written in the city of Wenzhou (Wen-chou) in the south-eastern coastal region in the middle of the 13th century. It recounts the hardships and cruelty of a young selfish scholar who is determined to attend the imperial examination in the capital. According to the nanxi convention the play was performed by seven actors, all of them specialised in their own particular types of role.

The male lead, called sheng, acts the role of the selfish scholar, Zhang Xie. The female lead is called dan. She plays the role of the poor orphan girl, who becomes the first wife of Zhang Xie. The clown character or chou, distinguished by his make-up, a white patch round the nose and eyes, appears, for example, in the roles of a fortune-teller, a villain, a servant god, and the Prime Minister.

- A scene from a 13th century play, Top Graduate Zhang Xie, showing a selfish scholar and a beauty in distress. The character types of later Chinese opera can be already recognised although the costuming is more modest than, for example, in the later Peking.

The role category, which is distinguished by its extremely stylised and usually colourful make-up, is called jing or painted face. In this play the jing actor appears in the roles of a friend of Zhang Xie, the mountain god, an elderly lady, and a prison guard. An actor of the mo type acts as a kind of master of ceremonies introducing the play and the main actors to the audience. Furthermore, he is seen in several minor roles. The supporting female actor, tie, plays the role of the Prime Minister’s daughter, who becomes Zhang Xie’s second wife. A second supporting female actor, wai, plays the role of the Prime Minister’s wife.

Seven actors in all are seen in the eighteen different roles. Acting styles vary according to the character portrayed. The sung “arias” and the spoken dialogue as well as the stylised dance-like movements, postures and gestures are all accompanied by music while the orchestra is present on the stage all the time.

The music of the northern zaju was dominated by its quick and rhythmic accompaniment, whereas the music of nanxi was softer, characterised by its lyrical, lingering melodies. The music of the present opera styles, of course, differs from the music of zaju and nanxi; however, this regional stylistic difference is still very much the same. The northern style is usually quicker and more accentuated, while the southern style is generally softer and more lyrical in character.