Classical Dance

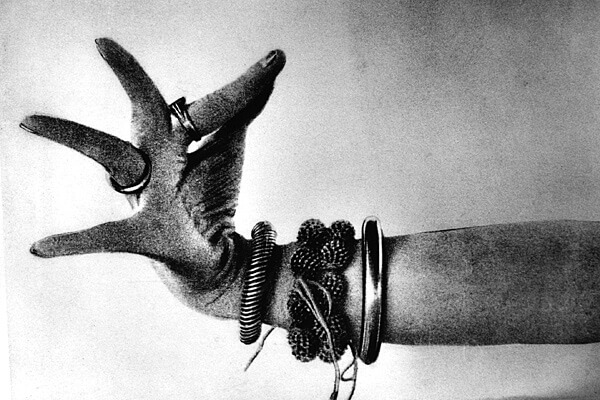

- Hand movement of a classical dancer From Raymond Cogniat: Dances d’Indochine. Paris 1932

Several types of dance exist in Cambodia. Pure dance is often referred to as robam, ancient dance as robam moram, dance-dramas as lakhon and the classical dance of today as lakhon kbach boran. The best preserved and most well known of them in the West is the classical tradition, which has been closely connected to the court for centuries.

The Royal Dance Troupe

To what extent the dance tradition of the Angkor is reflected in the classical dance of today is not exactly known. The Thai influence, on the other hand, is clearly recognisable in the court tradition of Cambodian dance. During the period when Cambodia was a vassal state of the Thais the bonds between Thai and Cambodian courts were close.

For example, King Ang Duong (1796–1859) had taken refuge in the court of Thailand (then Siam). It is said that he set new standards for his court dance, since he was inspired by the dances he had seen in Thailand. He even remodelled the dance costume after Thai models.

During the period of the French Protectorate Cambodian classical dance, which was much admired by the French colonialists, remained an integral part of the court tradition. Dance performances were also frequently staged for foreign dignitaries.

- Classical dancers in a kinnari dance From Raymond Cogniat: Dances d’Indochine. Paris 1932

During the reign of King Norodom (1860–1904) the royal dance troupe consisted of some 500 dancers divided into several sub-troupes. There were also several Thai dancers in the troupe and thus Thai dance and the genres of dance-drama were implanted in Cambodia to be later developed in a slightly different way than in neighbouring Thailand.

During the reign of King Sisowath (1904–27) the royal dancers visited Europe for the first time. The group and the king himself went to the Colonial Exhibition in Marseilles. The extremely successful visit aroused general interest in Cambodian dance and several Western artists were greatly inspired by it. The French sculptor Auguste Rodin painted sketches and wrote in praise of the dancers, and several Western choreographers, among them Ted Shawn, Ruth St Denis, Xenia Zarina, and Jean Börlin, composed their own orientalistic fantasy choreographies in the Cambodian spirit.

The successful visit to Marseilles was the first of several visits of the royal dance troupe to the West, which firmly established the fame of Cambodian dance in Europe. Otherwise, the reign of King Sisowath was a period of decline for court dance, as the number of dancers was reduced to about 100.

The Dancers

According to textual sources, it seems that the dancers in Angkor were most often offered to the temples and maybe also to the palace, where they served as kinds of servants, like the devadasis of medieval Hindu temples. During the later periods, when Theravada Buddhism and other aspects of culture were adopted from Thailand, the court dancers continued to belong to the court and they lived in the palace area.

Ritual performances were staged in temples and at other auspicious sites around the country, although the main task of the court dancers was to take care of the royal rituals. Performances for foreign guests were also staged. Officials and minor dignitaries could have their own dance troupes, often led by retired court dancers.

The court troupe mainly consisted of female dancers who were also often mistresses or minor wives of the king. In earlier times their sphere of life was strictly limited to the palace grounds and they were not allowed to marry while they served at court. It was in the 1940s, during King Sihanouk’s reign, that the dancers were allowed to live outside the palace area and marry.

The Repertoire

- Dancers performing in Thai-influenced costumes in a temple hall in Angkor Jukka O. Miettinen

- Dancers performing in Thai-influenced costumes in a temple hall in Angkor Jukka O. Miettinen

The Cambodian court dance tradition has been strongly connected to the Thai tradition for centuries. It was implanted in Cambodia because the young Cambodian princes were often educated at the court of Thailand and also because Thai dancers and dance teachers frequently visited and worked at the Cambodian court. In Cambodia the first standardisation of classical dance took place as early as the mid-19th century.

The Royal Dance Troupe was supported by the Royal Household at Phnom Penh under the name of lakhon lueng or “the King’s dancers” until 1970. In the twentieth century its repertoire has consisted of some 40 roeung dance-dramas and 60 pure dance numbers called robam, which are mostly group dances performed by women.

The performances originally formed part of court rituals, but they are now often aimed at general audiences, and innovations have been introduced to revive the ancient Khmer dances. This has resulted in hybrid compositions that combine the traditional Thai-influenced technique with poses, costume and jewellery copied from ancient Khmer reliefs from the Angkorean period.

Classical dance technique is employed by several forms of dance-dramas, from purely classical forms to folk traditions. The most grandiose of the dance-dramas is lakhon khol, which is still performed in both palace and village contexts.