Finland was one of the first countries to conduct artistic research, although it was not immediately referred to by that term. To the best of my knowledge, the first publication to use the term artistic research was titled Taiteellinen Tutkimus, and edited by Satu Kiljunen and Mika Hannula in 2001 (published in English as Artistic Research in 2002). One of the reasons is surely the historical sympathy for the spirit of the pioneer (grab a hoe, go to the mire and clear yourself a field). Finnish artists and art teachers tended to do first and to think later, afterwards. This approach has its problems, but it can also be considered a kind of meta-level practice-based research and ’author or maker-based’ research. If we had waited for philosophers to agree on terminology or the ontological and epistemological basis of artistic research, we might still not have begun. However, artistic research has been discussed for at least thirty years. I remember attending a symposium as a doctoral student in 1994, which, according to the report Knowledge is a Matter of Doing, was the first Nordic seminar to which both university scholars of theatre research and teachers and artists from art academies had been invited (Paavolainen & Ala-Korpela 1995, 5). However, when I started my doctoral studies in 1992 and completed them in 1998 (officially in 1999), there was no mention of artistic research, but rather doctoral studies, which had been divided into ones with artistic emphasis and ones with scientific emphasis. Previously, the term ’author-based’ or ‘maker-based’ research was often used, when one wanted to avoid talking about artistic research, which was considered a dangerous hybrid. The point was not really authorship, but rather the centrality of practice, especially the making of art. Of course, artistic practices are multifarious. Art is often exceedingly conceptual.

Another important reason for the rapid development of artistic research in Finland has been the independent university status of the major arts schools and national investments in doctoral education in all fields. Universities without practical art education have not been very interested in artistic practice as research. The majority of ’author- or maker-based’ or artistic research initially consisted of doctoral dissertations and doctoral thesis projects from art schools. Unlike in Sweden, for example, where the Committee for Artistic Research (Kommittén för Konstnärlig forskning) has operated under the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet), also publishing yearbooks on artistic research from 2004 to 2017, no research funding has been allocated to artistic research in Finland. However, in 2009, the Academy of Finland published a report assessing Finnish research in the fields of art in 2003–2007, especially in the four art universities operating at the time and the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Lapland. The report Research in Art and Design in Finnish Universities (2009) demonstrated, among other things, that artistic research was an existing phenomenon. Initially, the Academy of Finland recommended cooperation between researchers and artists, in such a way that the then Central Arts Council would have been responsible for the funding of artists. Subsequently, the Academy of Finland has funded artistic research, which has been evaluated in the context of research in social sciences or humanities. The first organisation to start funding expressly artistic research in Finland was the Kone Foundation.

The dualist model, according to which art and science should be kept separate, still had many advocates for a long time. The Universities Act continues to follow a bipartite model and maintains a dichotomy between scientific and artistic areas, so in legal terms it is not possible to blur boundaries. Ironically, this has been an important guarantee for the ability of art schools to develop artistic research independently. By guaranteeing parallel value for art and a special status for art universities, the law has paradoxically opened up new opportunities. Art academies have been able to independently develop their degree requirements even before introduction of the Bologna Process, which has been much maligned by European art schools. Its aim is to make EU doctoral studies, in addition bachelor’s and master’s degrees, comparable with each other. Unlike in Britain, where practice as research originated from the wish of universities to include the artistic work of their staff in their research results, artistic research in Finland has been an area of interest primarily at the level of doctoral education, because funding for art academies has been linked to the number of students rather than the research outputs of the staff. In the future, when Uniarts Helsinki will also be investing more in post-doc research and staff research, the situation will certainly change.

When setting up the Performing Arts Research Centre (Tutke), I strived as its first head in 2007–2009 to actively dismantle the division between doctoral degrees with scientific emphasis and artistic emphasis, because I believed that the exemptions given to degrees with artistic emphasis and the requirement for high-standard art placed on them were an obstacle to the development of artistic research, which was perceived as a dangerous hybrid. Together with Eeva Anttila and Esa Kirkkopelto, we introduced in Tutke the term artistic research as an umbrella concept, under which one could conduct many types of research, including, for example, research using qualitative methods in art pedagogy (Arlander 2009). Since then, I have tried to highlight the special features of artistic research and its own potential as well as the need to develop methods and practices specifically suited to artistic research (Arlander 2011; 2013a). In the early days, I talked about building a bridge between theory and practice. Now I would rather say, drawing from Karen Barad’s agential realism, that it is worth asking where and how the boundaries between theory and practice or, for example, artistic research and some other type of research have been or are set in each case (Arlander & Elo 2017).

Artistic research and more generally practice-based research are not only strongly developing research areas or fields, but also a methodological approach that is applied in, for example, theatre research alongside other methodological approaches. (Kershaw & Nicholson 2011) The preference of textual knowledge before embodied knowledge has been criticised for a long time in performance studies (cf. Conquergood 2004, Taylor 2003, Davis 2008, in Finnish Arlander et al. 2015). In cultural studies the aim is, in principle, to make the voice of as many knowledge producers as possible heard. When this idea is applied to artists, it is not without problems, because the artist’s position also includes privileges. Today, at least in a European framework, artistic research is a recognised albeit a controversial area of research and knowledge production. An example of this is the recent Vienna Declaration of Artistic Research, which has also been criticised (Cramer & Terpsma 2021). Although, for example, performance-as-research is still primarily thought of as a methodology, artists can, in principle, utilize a variety of methodological approaches (Smith & Dean 2009, 5).

Diversity and an openness to diversification are not easy to maintain, as it is often difficult for researchers to see a real justification for any research other than the one they were trained in. However, the relationship that different fields of art have with research and theoretical discussion varies, as well as the sciences characteristically related to each field of art; they then determine what these fields of art consider research to be. The lack of easily applicable common operating models and methods, which has been seen as a weakness in artistic research and an indication of how new the field is, can in fact be an important resource. A research strategy can be selected and built according to the subject and the researcher’s interests to serve that specific project, to bring together the expertise of various, even incompatible fields, and to highlight the knowledge, experience and understanding that may be produced through this particular project. Eclecticism and surprising combinations are an important counterbalance to increasingly narrow and specialised forms of knowledge production. With these strange combinations and special cases, the field of artistic research is at the same time growing in different directions, evolving and diversifying.

Despite the fact that a great deal has been written about artistic research, there are very few reflections on the different types of artistic research, i.e. typologies of artistic research. Most typologies are based on the relationship between art and academic research and some kind of dichotomy between art and science, such as James Elkins’ “The Three Configurations of the Studio-Art PhDs” (Elkins 2009). Others form a third area between art and academic research (Biggs & Karlsson 2011) or assume the centrality of some form of boundary work between them (Borgdorff 2012). Different combinations have also been proposed, such as science interpreting art, art interpreting science, art in the context of science, science in the context of art, art in the service of science, science in the service of art, etc. (Keinonen 2006). Perhaps the most well-known are typologies related to methodology on a more general level that add a third dimension to quantitative and qualitative methodology, such as performative research (Haseman 2006), arts-based research (Leavy 2009) conceptual research (Smith & Dean 2009).

In most cases, artistic research is understood as an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary activity. Different interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary connections and entanglements lead to different types of artistic research (Arlander 2016). Often, artistic research seems to have contact points with philosophical research, at least in terms of speculative freedom, even though artistic research inevitably also has its empirical dimension. We can therefore think of artistic research as a kind of speculation, not in the sense of philosophical speculation, but as an activity that focuses on imagining alternatives, as a form of speculation in and through practice. Many types of artistic research could be called speculative practices. What is essential is that speculation, imagination and experimentation take place through artistic practice.

In an English-language context, artistic research was earlier often referred to with the term practice, especially in connection with performing arts, which is evident from the names of anthologies such as Practice as Research – Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry (Barrett & Bolt 2007), Practice-as-Research in Performance and Screen (Allegue et al. 2009), Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts (Smith & Dean 2009) and Practice as Research in the Arts – Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances (Nelson 2013). In some cases the term performance is also used, such as in Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research (Riley & Hunter 2009) and Performance as Research – Knowledge, Methods, Impact (Arlander et al. 2018). Derivatives of the term practice are difficult to translate into Finnish (e.g. Humalisto 2012, 19–21). The use of the term has also been criticised for creating an artificial division between theory and practice as well as for failing to distinguish between artistic and other practices. Despite this criticism, there has been a shift in contemporary art from artistic practice, which primarily aims at producing an artwork, towards artistic activity that is carried out as an exercise, performance or contemplative or communal practice. This development is part of a trend since the 1960s that gained momentum during this century, of prioritizing art making, artistic practice, and also the ’working’ of art above the artwork as an object.

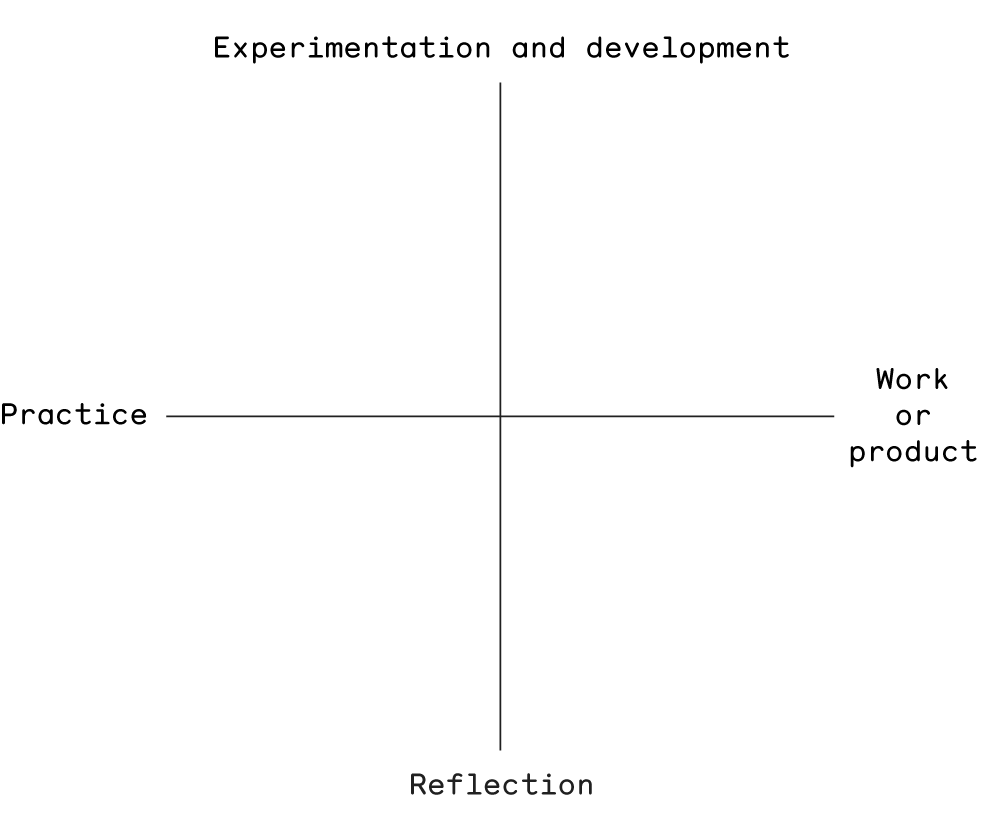

Below, I will present one possible model for illustrating the diversification of artistic research, or perhaps better for perceiving the variability of some of its features. I propose that research which aims to articulate and theorise an ongoing activity or practice and which is based on acquired (and therefore more or less unconscious) skills, sets its focus in different ways and often uses different methods than research which aims to develop and conceptualise an artwork or a new kind of design product and explain how that end result has been achieved. We can thus differentiate between: a) product-oriented artistic research that focuses on creating a work of art or design product; and b) practice-oriented or practice-led artistic research that focuses on an ongoing practice, often with a practical, critical or emancipatory knowledge interest. We can further simplify the idea and state that artistic research can be, on the one hand, product-oriented, when the main objective is to create an artwork or product, and, on the other hand, practice-oriented when engaging in a given practice is more important than an individual work or performance (Arlander 2011, 321). At first glance, this division could be linked to differences in emphasis between so-called creative and performing arts. However, contemporary art opposes such a dividing line, as it often focuses on processes and interaction instead of products or finished works. And practices can also be reified into product-like methods.

Another dimension relates to time, as the research process can be primarily developmental or experimental and strive to create something new. It can also be mainly reflective and attempt to understand and articulate something that has already been done. Both approaches, or rather both features, can be found in artistic research, even if one would expect the developing and experimental to dominate. However, for the critically oriented a reflective approach offers an opportunity to question, for example, the deeply ingrained conventions of the art world. For those with a more conservative orientation, it provides an opportunity to formulate and document so-called tacit knowledge and articulate the practices of an existing tradition.

A classic fourfold table can be made by combining these four features: product-oriented and experimental; practice-led and experimental; product-oriented and reflective; practice-led and reflective.

| Product-oriented (a) | Practice-led (b) | |

| Experimental (c) | (bc) | (ac) |

| Reflective (d) | (ad) | (bd) |

The same fourfold table may be more illustrative when characterised as dimensions:

General and simplified examples could be research projects that aim to develop a technical innovation (product-oriented and experimental/developmental) or a new exercise method (practice-led and experimental/developmental). Or a research project that aims to understand the experiences or reactions to a particular artwork or performance (product-oriented and reflective) or to criticise a specific exercise method (practice-led and reflective). In reality, it is difficult to find clear examples, as almost all research projects include, for example, a reflective and retrospective dimension simply because they are reported. And, as I stated earlier, almost all artistic research projects could be called speculative or experimental practices, if we think that speculation, imagining alternative models or methods takes place by means of artistic practice and in practice.

Such development of typologies may appear like a futile habit borrowed from social sciences, but ideally it can broaden and clarify as long as we remember that most artistic research involves all of these features, at least to some extent. I have presented the model here to, above all, emphasise that artistic research today can be appear and be realized in a variety of ways, and there is no need to imagine a definition that would work in all cases. When planning an artistic research project, it may still be useful to keep in mind that there is a difference between focusing on the research process and insights that may be gained during the process and focusing on the artistic end result or the artwork, as is usually the case in ordinary artistic work.

Sources

Allegue, Ludivine, Baz Kershaw, Simon Jones, and Angela Piccini, eds. 2009. Practice-as-Research in Performances and Screen. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Arlander, Annette. 2017. Artistic Research as Speculative Practice. www.jar-online.net/en/artistic-research-speculative-practice.

Arlander, Annette. 2017. “Practising art – as a habit? / Att utöva konst – som en vana?” Ruukku Journal, no 7, June 2017. ruukku-journal.fi/en/issues/7.

Arlander, Annette. 2016. “Artistic Research and/as Interdisciplinarity.” Artistic Research Does no 1, edited by C. Almeida and A. Alves, 1–27. Porto: NEA/12ADS Porto: Research Group in Arts Education/ Research Institute in Art, Design, Society; FBAUP Faculty of Fine Arts University of Porto.

Arlander, Annette. 2013a. “Artistic Research in a Nordic Context.” In Practice as Research in the Arts – Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances, edited by Robin Nelson, 152–162. Palgrave Macmillan.

Arlander, Annette. 2013b. “Taiteellisesta tutkimuksesta.” Lähikuva 3/2013, 7–24.

Arlander, Annette. 2011. “Characteristics of Visual and Performing Arts.” In The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts, edited by Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson, 315–332. Routledge 2011.

Arlander, Annette. 2009. “Artistic Research – from Apartness to Umbrella Concept at the Theatre Academy, Finland.” Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research. Scholarly Acts and Creative Cartographies, edited by Shannon Rose Riley and Lynette Hunter, 77–83. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Arlander, Annette, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude and Ben Spatz, eds. 2018. Performance as Research – Knowledge, Methods, Impact. London & New York: Routledge.

Arlander, Annette and Mika Elo. 2017. “Ekologinen näkökulma taidetutkimukseen.” Tiede ja Edistys 4, 335–346.

Arlander, Annette, Helena Erkkilä, Taina Riikonen and Helena Saarikoski, eds. 2015. Esitystutkimus. Helsinki: Kulttuuriosuuskunta Partuuna.

Barrett, Estelle and Barbara Bolt, eds. 2010 [2007]. Practice as Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry. London and New York: Tauris.

Biggs, Michael and Henrik Karlsson, eds. 2011. The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts. London and New York: Routledge.

Borgdorff, Henk. 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Conquergood, Dwight. 2004. “Performance Studies, Interventions and Radical Research.” In The Performance Studies Reader, edited by Henry Bial, 311–320. London and New York: Routledge.

Cramer, Florian and Nienke Terpsma. 2021. “What is wrong with the Vienna Declaration of Artistic Research.” onlineopen.org/what-is-wrong-with-the-vienna-declaration-on-artistic-research.

Davis, Tracy C., ed. 2008. The Cambridge Companion to Performance Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Elkins, James. 2009. “The three Configurations of Studio-Art PhDs.” In Artists PhDs – On the New Doctoral Degree in Studio Art, edited by James Elkins, 145–165. Washington DC: New Academia Publishing.

Haseman, Brad. 2006. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy: Quarterly Journal of Media Research and Resources. 118, 98–106.

Humalisto, Tomi. 2012. Toisin tehtyä, toisin nähtyä. Esittävien taiteiden valosuunnittelusta muutosten äärellä. Acta Scenica 27. Helsinki: Esittävien taiteiden tutkimuskeskus, Teatterikorkeakoulu. urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-9765-90-4.

Kershaw, Baz and Helen Nicholson, eds. 2011. Research Methods in Theatre and Performance. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Keinonen, Turkka. 2006. “Fields and Acts of Art and Research.” In The Art of Research. Research Practices in Art and Design, edited by Maarit Mäkelä and Sara Poutarinne, 41–58. Helsinki: University of Art and Design.

Kiljunen, Satu and Mika Hannula, eds. 2001. Taiteellinen tutkimus. Helsinki: Kuvataideakatemia.

The Committee for Artistic Research. www.vr.se/english/about-us/organisation/scientific-councils-councils-and-committees/the-committee-for-artistic-research.html

Leavy, Patricia. 2009. Method Meets Art – Arts-Based Research Practice. New York and London: The Guilford Press.

Nelson, Robin, ed. 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts – Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Paavolainen, Pentti and Anu Ala-Korpela, eds. 1995. Knowledge Is a Matter of Doing. Acta Scenica 1. Helsinki: Teatterikorkeakoulu.

“Research in Art and Design in Finnish universities.” Publications of the Academy of Finland 4/09. www.aka.fi/globalassets/awanhat/documents/tiedostot/julkaisut/04_09-research-in-art-and-design.pdf.

Riley, Shannon Rose and Lynette Hunter, eds. 2009. Mapping Landscapes for Performance as Research. Scholarly Acts and Creative Cartographies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Smith, Hazel and Roger T. Dean, eds. 2009. Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Taylor, Diana. 2003. The Archive and the Repertory. Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Durham: Duke University Press.

Vienna Declaration of Artistic Research. cdn.ymaws.com/elia-artschools.org/resource/resmgr/files/vienna-declaration-on-ar24-j.pdf.

Contributor

Annette Arlander

Annette Kristina Arlander is an artist, researcher and teacher, and one of the pioneers in Finnish performance art, and a trailblazer in artistic research. She graduated as director in 1981 and Doctor of Arts in theatre and drama in 1999, worked as a Professor of Performance Art and Theory at the Theatre Academy from 2001 to 2013, as Professor of Artistic Research in Uniarts Helsinki from 2015 to 2016, and as Professor in Performance, Art and Theory at Stockholm University of the Arts from 2018 to 2019. She is currently a visiting researcher at the Academy of Fine Arts of Uniarts Helsinki. More information at annettearlander.com.