With the emergence of modern dance in the early 20th century, African visual arts, dance forms and storytelling traditions influenced artists around the world who were moving from late Romanticism to modernism. In the United States, discrimination against Black people was reflected in stereotypes in the press reviews of dance works and in a pervasive segregation of society. At its most extreme, the violence took the form of public executions by whites, lynchings that went mostly unpunished and which both Black and white artists protested against with their critical works. Segregation meant that people went to different restaurants to dance, studied and taught dance in different schools, performed in different venues and stayed in different hotels on tours. However, many dancers and choreographers wanted to perform for audiences that were both Black and white. They wanted the same educational and employment opportunities for Blacks as whites had. They had to claim these rights while practising their professions as dancers, teachers and choreographers. This article looks at how this struggle was reflected in their art.

Black dancers, choreographers and dance teachers turned African, Caribbean and African American styles into modern dance. This dance, produced by Black artists themselves, was different from the way whites exploited these styles by incorporating them into their own dance. Black dancers and choreographers were in a difficult position because they were not allowed into white spaces and institutions, but in the other direction segregation was non-existent, meaning that whites felt they could exploit Black culture in the same way that they had exploited the work of Black bodies during slavery. Africanisms, or African, African Caribbean and African American stylistic features, can be seen in all 20th-century art dance.[1] For the pioneers of modern dance, the use of Africanisms in dance was often socially charged, political and critical of racism, showing African and Caribbean influences as valuable and beautiful. Afrodiasporic modern dance, in contrast, refers to the art dance created by people who emigrated from Africa or their descendants between the early 20th century and the 1960s, which gave rise to the African American concert dance aesthetic.[2] One of its central themes is the particular discourse and consciousness made possible by living in the Afrodiaspora: the simultaneous sense of interiority and exteriority and the perception of cultural roots in Africa.[3]

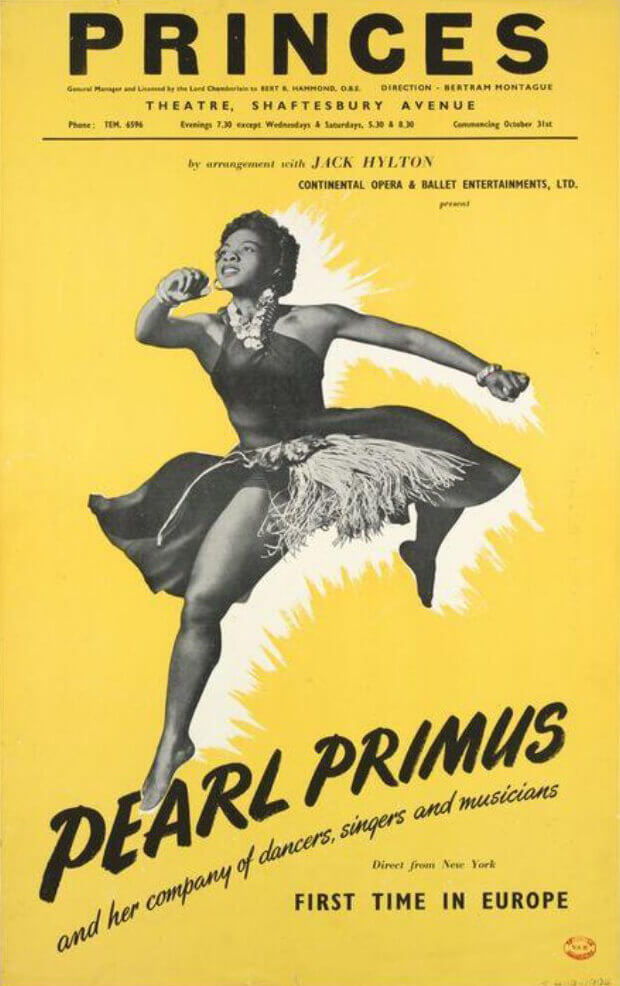

Despite the oppression of Black people, Katherine Dunham (1909–2006), Talley Beatty (1918–1995), Pearl Primus (1919–1994), Donald McKayle (1930–2018) and Alvin Ailey (1931–1989) managed to form their own companies, with whom they toured extensively. Dunham used her studies in anthropology at the University of Chicago to develop her technique. Field trips to the Caribbean and Africa and ballet studies alongside her university studies enabled a fusion, where Dunham combined elements of ballet and various forms of African Caribbean folk dance – while also participating in the creation of a whole new discipline, dance anthropology. She was active in popular entertainment, dance art and academia, using her theoretical tools in dance practice and her technical knowledge of dance in her academic research.[4]

In contrast, Primus rose to prominence in New York, dancing in the works of choreographer Sophie Maslow, among others. In 1943, she performed with Asadata Dafora (1890–1965), a singer, dancer and choreographer from Sierra Leone who worked in Europe and the United States, at the legendary New York concert venue, Carnegie Hall. Primus studied the techniques of Martha Graham and Doris Humphrey, and was encouraged by Helen Tamiris and Anna Sokolow.[5] Ailey, meanwhile, gained exposure in Los Angeles at the Lester Horton School of Dance and Dance Theater, where he studied and performed for five years in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The Lester Horton Dance Theater was the first modern dance theatre in the United States. After Lester Horton’s death, Ailey worked at the theatre as a teacher and choreographer.[6] In 1954–55, he got to perform with another Lester Horton dancer, Carmen de Lavallade, in the musical House of Flowers on Broadway in New York.[7]

All of the above pioneers had to perform early in their careers in works that reinforced stereotypical ideas about Black culture rather than challenging them. Dunham, Beatty, Primus, McKayle and Ailey all dealt with a wide range of Afrodiasporic identities and experiences throughout their careers. Their works reflect pride in African and Caribbean dance cultures, but also point to inequalities between whites and Blacks and to the collective trauma of oppression.

The global influence of African-American culture is also reflected in how Pan-African modern dance practitioners in Africa and elsewhere have formed new conceptions of modern dance. Pan-Africanism has taken, and continues to take, a variety of forms and meanings in different contexts over time. It has its roots in the 19th century and it influenced, for example, the formation of the African Union. The term has been used to describe the pursuit of unity between people living on the African continent and those living in the diaspora, as well as artistic movements that reinforce Africanism and give it visibility. Pan-Africanism has manifested itself in art as figures returning from the diaspora to Africa to experience metaphorical, spiritual and literal healing. Furthermore, Pan-Africanism has meant knowledge of Africa-centric doctrines and traditions and the links between diasporic and African art forms. Participation in the civil rights struggle in the United States, for example, has been Pan-Africanism.[8] Contrary to the idea of Pan-Africanism, the role of US Black modern dance practitioners touring Africa in the 1960s was to remain silent about the discrimination they experienced at home in the name of the struggle against communism. At the same time, the Soviet Union used discrimination against Blacks in the United States as a propaganda weapon.[9]

Working in the field of dance required artistic activism. In the 1930s and 40s, Dunham had to demand proper fees and treatment for her company, and access for Black audiences to white theatres.[10] Primus had to challenge the essentialist views of the critics. Although Primus wanted to show Caribbean and African dance cultures as sophisticated and to convey their dignity to the audience in her works, the critics did not always see the complexity and intellectuality of her choreographies. Critics could see in Trinidadian-born Primus a “raw athleticism,” “passion” and “animalistic energy,” while failing to mention the difficult polyrhythm of the dances and the research the works required into the history of dance in order to analyse and fit this movement language to the norms of modern performing arts. Interested in democracy and humanism, Primus wanted to create opportunities for mutual respect and dialogue between cultures, and challenged the critics’ misunderstandings and degrading views of Africanism time and again by emphasising the humanism and universality of her Afrocentric art.[11]

Danced Protests against Violence

The early part of Dunham’s career is connected to the Harlem Renaissance, or the New Negro movement in art, from the late 1910s to the late 1930s. During this period, Black artists drew on Afrodiasporic folklore to transform prevailing perceptions of African American, African and Caribbean people into less stereotypical ones and to expand US understanding of national identity to also include the contributions of Black people. Dunham, too, believed that high-quality art based on Black folklore could change people’s perceptions and lead to a more equal society.[12] In contrast, Primus’ career can be seen to bridge the Harlem Renaissance and the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 70s.[13] In 1941, Primus was the first Black dancer in the left-wing New Dance Group, founded by white people. This group saw dance as a vehicle for change.[14] For Black artists, it was crucial to foster a Black identity through art, that is, to create a shared, distinct culture for the Black community.

Primus’ Strange Fruit (1943/1945) and Dunham’s Southland (1950) were staged dance protests against the lynchings of Black people by whites. Both women were extremely brave in making this violence the subject of dance works. These works made visible how the United States, which was fighting fascism abroad, practised fascism against its own people. In Strange Fruit, Primus portrayed a white woman’s distress after the lynch mob had left and she was left to look at a burnt body hanging from a tree. Primus initially performed the solo with an actor reciting the poem Strange Fruit, written by Lewis Allan (pseudonym of Abel Meeropol). In the silence, the audience could hear Primus gasping, pounding her fists, running and throwing herself to the floor, and experience the pain of witnessing a lynching.[15] With Southland, however, US authorities tried to silence Dunham. They suspended performances and stopped financially supporting Dunham’s dance company. Her company was no longer allowed to represent the United States.[16] The paucity of press coverage of Southland in thearchives is a stark testimony to the power of the state: the work was banned from being performed and written about in newspapers in Dunham’s home country.[17] For Afrodiasporic dance artists, however, this work came to signify strength and the courage to define themselves and to think differently in the context of white supremacist constraints.[18]

Primus’ Hard Time Blues (1945) and Beatty’s Southern Landscape (1949) dealt with the oppression of sharecroppers and terrorism by white supremacists in the southern United States. In Hard Time Blues, Primus portrayed a Black man who was a sharecropper. Whereas in Strange Fruit the dancing was close to the floor, in Hard Time Blues the choreography included high stationary jumps with the knees bent in the air close to the torso.[19] These jumps later became a distinctive feature of Primus dance. According to a review published in Ebony magazinein1951, they made the audience gasp for breath. At the time, Primus had recently returned from a field trip to Africa. Her dance school, Pearl Primus School of Primal Dance, opened shortly afterwards.[20]

Southern Landscape, based on the novel by Howard Fast, represented a community of Black and white sharecroppers that the Ku Klux Klan destroyed by burning the farms and killing almost all the farmers. Survivors went out at night to retrieve the dead from the fields and to bury them in secret. Beatty’s choreography captured the anger and desperation of the people who had been attacked by using energetic, fast and trembling movements. The theme was common to many Blacks, but like lynchings, discrimination has often been seen only a problem for the rural South. The canonised history of slavery has overshadowed much of the history, including racism, experienced by Blacks in the cities. Beatty included in Southern Landscape a contemplative, mournful solo, The Mourner’s Bench (1947), which he danced on and around a simple bench. It featured skilful balancing on the bench and landings to the ground.[21] Beatty fused movements from classical ballet, modern dance and jazz dance, alternating inward and upward gestures. The choreography expressed the human ability to escape painful events by either withdrawing into one’s own world or reaching for a higher spiritual reality.[22]

In the following decades, the tradition of protest dances was continued, for example, by McKayle’s Rainbow ’Round My Shoulder (1959) and Ailey’s Masekela Langage (1969). McKayle depicted Black men suffering excessive prison sentences doing gruelling forced labour, building a road into a cliff with picks in their hands. The work was a critical intervention: it made injustice visible while mobilising a Black audience. In this way, it placed itself in the continuum of sit-in protesters. In prison slang, “rainbow” was a pick used by prisoners, because the pick’s movement could form a rapidly disappearing rainbow as the prisoner waved it in the air. The choreography showed the men as strong and capable people whose potential was lost in a society that equated dark skin with criminality and made Black men build “progress,” highways and railroads, without human rights. Like Beatty’s The Mourner’s Bench, however, McKayle’s Rainbow ’Round My Shoulder was about the human capacity to imagine and use imagination as a source of strength in a terrible situation.[23]

While Ailey’s Masekela Langage wasin progress, 21-year-old Black Panther activist Fred Hampton was shot in his home, and Ailey was deeply touched and outraged by the news. In this context, the work was no longer just about the hopelessness and rage felt by people living under apartheid in South Africa, as originally conceived, but also about the violence faced by Black people in the United States.[24] The work is one of the most intense, hard-hitting and poignant in Ailey’s oeuvre. It is set to music by South African trumpeter and composer Hugh Masekela, music that Masekela himself considered a collection of protest songs.[25] Ailey had drawn a parallel between apartheid and the violence faced by African Americans in the United States in the programme he wrote for a 1970 tour of the Soviet Union, but this was censored. For the Soviet tour of Masekela Langage they also had to remove the tragic final scene in which a beaten man danced a heartbreaking solo and died on the floor of a bar. Ailey himself had suffered police brutality in his home country when he was mistaken for another man by the police, arrested and beaten in jail.[26]

Afrodiasporic Aesthetics

Primus and Dunham contributed to the emergence of dance anthropology as a discipline and created early ethnographies of performance, drawing on their own fieldwork in the Caribbean and Africa.[27] In the 1920s, the writer and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston had already studied Vodoun in New Orleans and its connections to Haiti and West Africa, using the rhythms of the speech of the Black community in New Orleans in her writing.[28] Dunham conducted research on dances of African origin in Haiti, Trinidad, Martinique and Jamaica between 1935–36.[29] In Vodoun, she was interested in the knowledge she gained through participant observation of the line drawn in the water between being possessed by the spirit and performing a dance.[30] Immediately after her trip, Dunham produced his work L’Ag’Ya (1938), which takes its name from the Martinique martial dance called ag’ya. In L’Ag’Ya, Dunham combined ballet, modern dance, Cuban habanera, Brazilian majumba and the Martinique mazouka, beguine and ag’ya. The choreography reflected the social contradictions that existed in Martinique in the 1930s. Through the combination of styles, Dunham reflected the creolisationin[31] Martinique, i.e., the fusion and transformation of performances and forms of expression in cultural encounters.[32]

After L’Ag’Ya, Dunham researched the history of urban Black dances in the United States. African American vernacular dance movements of the 1920s (such as the Black Bottom and the mooch) became part of the Dunham Company’s touring repertoire.[33] These included Flaming Youth, 1927 (1940), performed, for example, in 1950 in Argentina’s capital Buenos Aires.[34] It also became part of the second version of a show called Tropical Revue. Dunham understood the connection between African American vernacular dances and dances she had observed in the Caribbean and even African religious ceremonies.[35]

Primus travelled to West Africa in 1948 and did fieldwork in Nigeria and what was then the Belgian Congo (later Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo). She also travelled to the Gold Coast (now Ghana), Angola, Cameroon, Liberia and Senegal. Primus travelled from village to village, crossing national borders and exploring the dances of at least 30 different cultural groups.[36] The journey transformed Primus as a person and as an artist. Africanism began to show up in her work as a deepening and broadening of storytelling. Stories also became a central part of her dance pedagogy.[37] The African tradition of storytelling can be seen, for example, in Griot (1989), a work with dancer Linda Spriggs. The dancer plays the dual role of two men: on one hand, he is the griot, or storyteller, and on the other, Shango, the god of thunder and lightning the griot is transformed into during the dance. Shango accidentally burns down his own village and kills his wife because he cannot control his destructive power. After realising this, Shango loses his mind and kills himself. Rehearsing and performing Shango’s mental breakdown and loss of control was difficult for Spriggs, but as an artist she found a point of identification with Shango. Spriggs had found that overcoming obstacles as a woman artist was not in any way attractive, but required directness and revolutionary qualities, neither of which were commonly considered feminine. Griot’s premiere was made particularly emotionally challenging by the news of Alvin Ailey’s death on the same day. Spriggs had previously danced in Ailey’s company.[38]

All forms of Afrodiasporic aesthetics are reflected in the works of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre, founded in 1958. Ailey’s stunning classic Revelations (1960) seamlessly combines the aesthetics and techniques of modern dance, jazz dance and ballet. Countless choreographers, including Ailey himself, have subsequently referenced parts of this work. Revelations stems from music: African American spirituals that carry the work from sorrow to joy. The first three movements of the work make visible the violence by whites against those they enslaved, and the pain this has caused to Black people. The joy that the work advances towards is the joy of political survival, still retaining the fighting spirit.[39] The choreography displays many of the features that make modern dance Afrodiasporic: the undulating isolations of the upper body that grow into an ecstatic dance of the whole body at the centre of the work, the percussiveness of movement, syncopation, angular postures and forms, and the polycentricity of movement.[40] In The River (1970), these elements are linked with equally impressive stylistic features drawn from the ballet aesthetic. The River was originally a collaboration between Ailey, composer Duke Ellington and the American Ballet Theatre.[41] In it, Ailey explored major themes typical of his work, also referencing Revelations: human interaction, same-sex desire as part of the broader African American community, flow and rupture in flow, discontinuity as part of continuity, and a utopian world without stylistic boundaries of movement or musical language.[42]

Pan-African Modern Dance

Dafora’s work Kykunkor, or the Witch Woman (1934) is an early example of Pan-Africanism in modern dance.[43] It is the first opera performed in African languages by artists of predominantly African descent in the United States.[44] In Kykunkor, Pan-Africanism is an affective identification surface created by the rhythm of drum music and dance.[45] Following the independence of African states from colonial rule in the second half of the 20th century, Pan-Africanism took on a new meaning in modern dance. Today, Pan-Africanism means that different African and Afrodiasporic dance forms can be used to found their own specific yet universal modern dance techniques. The dance scholar Kariamu Welsh Asante (1949–2021) calls the universal African technique she has developed umfundalai. Its aesthetics are based on three features common to African arts: polyrhythm, polycentrism and curvilinearity in form, shape and structure. Polyrhythm refers to the simultaneous presence of many different rhythms in the dancer’s body, while polycentrism refers to movements coming from many different directions at the same time and moving at different speeds. Curvilinearity refers to different circular or curvilinear forms.[46]

Germaine Acogny (b. 1944), who began her career in the 1960s, calls her synthesis a new African dance. It combines several African dance forms with modern ballet, Graham technique and contemporary dance to create a kind of Pan-African dance.[47] Acogny has codified this Pan-African modern dance technique, which is taught at the École des Sables dance school in the village of Toubab Dialawi, near Dakar, Senegal. The Germaine Acogny technique is taught by certified instructors and focuses on specific exercises in a ring, images of nature, animals and cosmology, movements and gestures, breathing, play and the connection between dancers and musicians, as well as the dancer’s own bodily truth and their background.

The Acogny technique originated after Acogny received inappropriate assessments from her ballet teacher in France about the shape of her feet and the size of her buttocks. As a result of this experience, she decided to use ballet to create her own inclusive and Africanist technique, where her or anyone else’s physical features could not be considered wrong.[48] The Acogny technique and the École des Sables offer dancers the opportunity to form Pan-African movement languages from dances that have survived the effects of hundreds of years of enslavement, colonialism and neocolonialism.[49] In addition to professional training, the school organises workshops for dancers at all levels, where contemporary African choreographers teach their own techniques and traditional dance techniques from different African countries.

In addition to her pioneering pedagogy, Acogny has choreographed her own solo and group works, which take a stand on specific themes but are simultaneously abstract. She created Fagaala (2002), a work on the Rwandan genocide, for her Jant-Bi group in collaboration with butoh artist Kota Yamazaki. The works and pedagogy of choreographers like Acogny defy ballet and other colonising dance forms like it, but they also exploit and transform them. At the same time, they push for a change in the way we in the Global North understand African traditions. Acogny’s African dance is a demanding, systematic, disciplined and artistic technique in which one can progress from level to level. It requires the dancer to ground themselves on a variety of surfaces, such as an uneven sand-covered floor, and adapt their dancing to its demands. It is in the core of modern dance techniques.[50] This perspective challenges the Western perception of African dance forms as less important to professional dance training than ballet, modern or contemporary dance as they are traditionally taught.

The originality of African modern dance can be seen in Acogny’s solo work A un Endroit du Début (2015), in which she explored the story of her own family through Aloopho, her Yoruba grandmother. Aloopho was a matriarch whose son, Acogny’s father Togoun, cut ties with her when he converted to Catholicism in a failed attempt to prevent the animistic heritage from being passed down from grandmother to grandchildren. The work deals with the Catholic legacy left by colonialism and the animistic heritage of the matriarch. In the work, Acogny forgives her father his defiance and threat to the transmission of knowledge between women and confirms her own connection with Aloopho. Acogny presents the different levels of history in interlaced projections. Autobiography, myths and epochs appear on stage as simultaneous layers through which the dancer moves. She deals with the acculturation resulting from colonisation and the loss and recovery of identity and self-esteem as collective wounds and their healing.[51]

The various forms of Afrodiasporic and Pan-African modern dance live on in the 21st century, giving rise to different contemporary dance trends. Within Afrodiasporic and Pan-African modern dance, exemplary works, training institutions and techniques have been created. The Katherine Dunham School of Arts and Research was more than just a dance school teaching the Dunham Technique in New York in the 1940s and 50s. It offered many courses in humanities and social sciences, such as psychology or philosophy.[52] Dunham Technique teacher Saroya Corbett says that women in her family have been studying the Dunham Technique for generations and that one of her missions is to pass on the Dunham legacy to future generations.[53] The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which began in the late 1950s, in keeping with Ailey’s vision has the mission to serve as a repository of modern dance programming, both preserving and presenting important works of modern dance and providing ongoing training for dancers and audiences. The pioneers of modern Afrodiasporic and Pan-African dance believed in a multifaceted education that would allow them to build their own artistic vision and to respectfully challenge the work of previous generations.

Notes

1 Aspects of style adopted from African American vernacular or social dances are, for example, the central building block of George Balanchine’s neoclassical ballet style; Dixon Gottschild 1998, 59–79.

2 Foulkes 2002, 52.

3 Kowal 2010, 118.

4 Strom 2010, 291.

5 Schwartz 2011, 3, 30–31.

6 Dunning 1996, 44, 59, 67–69.

7 Dunning 1996, 78–88.

8 Tomlinson 2017, xvii–xviii.

9 Croft 2015, 67.

10 Hill 2002, 291–292.

11 Brown 2015, 128–131.

12 Lamothe 2008, 115–116.

13 Brown 2015, 103.

14 Brown 2015, 101.

15 Schwartz 2011, 35–36.

16 Hill 2002, 304–305, 309.

17 Hardin 2016, 50.

18 Hill 2002, 311–312.

19 Schwartz 2011, 36–37.

20 Schwartz 2011, 94–95.

21 Perpener n.d.

22 Kowal 2010, 205, 207–208.

23 Kowal 2010, 216–225.

24 DeFrantz 2004, 117–121.

25 Dunning 1996, 246–248.

26 Croft 2015, 99–103.

27 Clark uses the name “research-to-performance method” for Dunham’s performance ethnography, Clark 1994, 190. Corbett uses the term “performed ethnography,” Corbett 2014, 93–94.

28 Turner 2009, 13–15.

29 Aschenbrenner 2002, 58–81.

30 Lamothe 2008, 125–127.

31 Clark 1994, 193, 196.

32 Baron & Cara 2011, 12.

33 Corbett 2014, 92.

34 Clark 1994, 191, 198.

35 Lloyd 1949/1974, 250.

36 Primus worked in Liberia and Ghana again in 1959–62, Schwartz 2011, 72, 143.

37 Schwartz 2011, 19–20, 78.

38 Schwartz 2011, 224–228.

39 Croft 2015, 92–93.

40 DeFrantz 2004, 3–13.

41 DeFrantz 2004, 148–155.

42 DeFrantz 2004, 153.

43 Franko 2002, 76–84.

44 Needham 2002, 233.

45 Franko 2002, 82–84.

46 Mfundalai: Asante 2001, 144–147 and umfundalai: Mills 1994, Nance 2019.

47 Sörgel 2020, 36.

48 Swanson 2019, 49–51.

49 Swanson 2019, 57–59.

50 Foster 2010, 125.

51 Malécot 2021, 22–23.

52 Corbett 2014, 93–94.

53 Evans 2014, 52–55.

Literature

Asante, Kariamu Welsh. 2001. “Commonalties in African Dance: An Aesthetic Foundation.” In Moving History / Dancing Cultures, Ann Dils and Ann Cooper Albright (eds.), 144–151. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Aschenbrenner, Joyce. 2002. Katherine Dunham: Dancing a Life. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Baron, Robert & Cara, Ana C. 2011. “Creolization as Cultural Creativity.” In Creolization as Cultural Creativity, Robert Baron and Ana C. Cara (eds.), 12–23. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Brown, Tammy L. 2015. City of Islands. Caribbean Intellectuals in New York. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Clark, Vévé. 1994. “Performing the Memory of Difference in Afro-Caribbean Dance: Katherine Dunham’s Choreography, 1938–87.” In History and Memory in African American Culture, Geneviève Fabre and Robert O’Meally (eds.), 188–204. New York: Oxford University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Corbett, Saroya. 2014. “Katherine Dunham’s Mark on Jazz Dance.” In Jazz Dance. A History of the Roots and Branches, Lindsay Guarino and Wendy Oliver (eds.), 89–96. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Croft, Clare. 2015. Dancers as Diplomats. American Choreography in Cultural Exchange. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

DeFrantz, Thomas F. 2004 Dancing Revelations: Alvin Ailey’s Embodiment of African American Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pro Quest Ebook Central.

Dunning, Jennifer. 1996. Alvin Ailey. A Life in Dance. Reading: Addison–Wesley Publishing Company.

Evans, Stephanie Y. 2014 Black Passports: Travel Memoirs as a Tool for Youth Empowerment Albany: State University of New York Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Foster, Susan Leigh. 2010. “Muscle/Memories: How Germaine Acogny and Diane McIntyre Put Their Feet Down.” In Rhythms of the Afro-Atlantic World. Rituals and Remembrances, Mamadou Diouf and Ifeoma Kiddoe Nwankwo (eds.), 121–135. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Foulkes, Julia L. 2002. Modern Bodies: Dance and American Modernism from Martha Graham to Alvin Ailey. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Franko, Mark. 2002. The Work of Dance: Labor, Movement, and Identity in the 1930s. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. 1998 Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance: Dance and Other Contexts, Westport: Praeger.

Hardin, Tayana L. 2016. “Katherine Dunham’s Southland and the Archival Quality of Black Dance.” The Black Scholar, 46:1, 46–53. Accessed 18 December 2020 https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2015.1119635 (Haettu 18.12.2020).

Hill, Constance Valis. 2002. “Katherine Dunham’s Southland: Protest in the Face of Repression.” In Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Thomas F. DeFrantz (ed.), 289–316. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Kowal, Rebekah J. 2010. How to Do Things with Dance: Performing Change in Postwar America. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Lamothe, Daphne. 2008. Inventing the New Negro: Narrative, Culture, and Ethnography. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Lloyd, Margaret. 1949/1974. The Borzoi Book of Modern Dance. New York: Dance Horizons. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Malécot, Laure. 2021. “Germaine Acogny.” In Fifty Contemporary Choreographers, Jo Butterworth and Lorna Sanders (eds.), 19–23. Abingdon: Routledge.

Mills, Glendola Rene. 1994. “Umfundalai One Technique, Three Applications.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 65:5, 36–47.

Nance, C. Kemal. 2019. “Friction: male identity and representation in Umfundalai.” In Dance and the Quality of Life, Karen Bond (ed.), 245–260. Cham: Springer.

Needham, Maureen. 2002. “Kykunkor, or the Witch Woman: An African Opera in America, 1934.” In Dancing Many Drums: Excavations in African American Dance, Thomas F. DeFrantz (ed.), 233–266. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Perpener, John. n.d. Talley Beatty. Accessed 22 December 2020 https://danceinteractive.jacobspillow.org/themes-essays/african-diaspora/talley-beatty/.

Schwartz, Peggy & Murray. 2011. The Dance Claimed Me. A Biography of Pearl Primus. New Haven: Yale University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Strom, Kirsten. 2010. “Popular Anthropology: Dance, Race, and Katherine Dunham.” In The Popular Avant-Garde, Renée A. Silverman (ed.), 285–298. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Swanson, Amy. 2019. “Codifying African dance: the Germaine Acogny technique and antinomies of postcolonial cultural production.” Critical African Studies, 11:1, 48–62.

Sörgel, Sabine. 2020. Contemporary African Dance Theatre. Phenomenology, Whiteness, and the Gaze. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tomlinson, Lisa. 2017 The African-Jamaican Aesthetic: Cultural Retention and Transformation Across Borders. Leiden: Brill Rodopi. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Turner, Richard Brent. 2009. Jazz Religion, the Second Line, and Black New Orleans. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Contributor

Hanna Väätäinen

Hanna Väätäinen (PhD) teaches courses on the history of jazz dance, the history of ballet, the history of modern and contemporary dance and the history of Finnish art dance at Turku University of Applied Sciences. She is interested in improvisation in dance and its research, poetry, craft activism and comics. kirjosarjis.blogspot.com