This book is based on the 2022 textbook, Näkökulmia tanssitaiteen historiaan ja nykypäivään, the first comprehensive presentation in Finnish of the historical trajectories and features of Western dance as a performing art. Like its Finnish original, this book is an approachable general textbook that describes, presents and analyses its topic from the many perspectives relevant to dance art in the 2020s. The Finnish original was intended for a Finnish-speaking audience, and this is somewhat reflected in this translation, in, for example, which authors and works are discussed in depth.

This translation emerged from the needs of the UNIARTS MA programmes where tuition is offered in English as well as the internationalisation of the field of dance and performance in general. The book is organised chronologically because, alongside the complexity of the world, we editors recognise the need to structure the history of dance in a manner that considers artists and creators in relation to the frameworks and phenomena of their own era. Despite the chronological structure, the volume is not intended to be read from beginning to end. Rather, the articles intersect through internal references and shared themes. The advantage of the electronic format is not only the flexibility of navigation, but also the ability to update the volume in the future, for example by adding articles on important phenomena currently underrepresented.

The purpose of the book is to approach history from the present: to reread the canon, to consider what in the past resonates now, and to highlight previously excluded histories and neglected figures. We are aware that in the 2020s we need to question any Eurocentric history that emphasises almost exclusively white actors and normative bodies. We are only at the beginning of this development. Even so, we hope that this book will enrich and broaden our understanding of dance art – of how dance has been, at different times, a diverse field of artistic thought, experimentation and development, always in relation to its cultural environment.

The topics covered in the book range from the long histories of using ritual practices or Antiquity to justify dance as art, from the different influences of ballet and Afrodiasporic practices to the interaction between dance and technology in the 21st century and disability dance. The 18 contributors are experts in their fields, artists and researchers. They represent the intertwining of practice and research that makes dance research in Finland so special. This organic bond is evident in the need to verbalise dance as a bodily practice and the way the authors write about dance and understand choreographic processes and dance as a part of culture and society. We have challenged the authors to explore their topics in new ways and to consider the thematic connections between different chapters. Because of their different backgrounds, the authors draw on a wide range of sources, from dance works to historical archives and from artistic practices to current theoretical debates. Instead of homogenising their voices, we editors have sought to preserve the authors’ own interpretive emphases.

The perspectives and themes selected for the book reflect the impact of research and theoretical discourses around performance on both university dance education and among contemporary dance practitioners. At the same time, the traditional master-pupil style of art education has almost disappeared from higher education in the arts and the classroom has become a space for critical debate. The study of the history of dance has expanded from artists’ biographies and aesthetic chronologies of works to an examination of the conditions and possibilities of dance art, and an analysis of the expressive languages and artistic aims of dance as a question of its relationship to the world.

Today, digital accessibility to authors, works and research has enriched the understanding of the complexity of history and the present. We can simultaneously examine multiple, heterogeneous and even contradictory understandings of what is happening in dance art, what is significant and for whom, and in what different frames of reference art becomes relevant. Dance makers can each define their own relationship to history. They operate within many different frames of reference and in new global networks and contexts.

Each section of the book begins with a brief summary of the content of the articles in that section.

Stories of Origin

This section explores how dance’s distant past shapes our current understanding and the many different ways in which ideas about dance that happened thousands of years ago have served as a model and an ideal for European dance art in particular. Antiquity around the Mediterranean has been used to justify notions of classicism and proper form as well as a need to break with these norms. Similarly, dances marked as ritualistic, usually from outside of Europe, have both supported arguments about the eternal significance of dance and challenged Eurocentric ways of defining what art actually is.

The section opens with Jukka O. Miettinen’s article Dance and Rituals, which unpacks anthropological understandings of the meaning of rituals and the ways in which rituals have inspired dance makers. In particular, non-European rituals have challenged notions of spirituality, anthropocentrism and audience relations in dance art, while dissolving boundaries between the performing arts.

In her article Unlocking the Ancient Art of Dance: Dance as a Profession, Manna Satama asks what it was like to make a living as a dancer two thousand years ago. Satama approaches Greco-Roman dance in the Eastern Mediterranean from the perspective of employment contracts, essays and other contemporary sources, looking at issues such as what body features or skills dancers had to pay particular attention to and why, and what it was like to train to be a dancer.

Manna Satama’s and Vesa Vahtikari’s Dancing Chorus in Ancient Greek Drama describes the various roles of the chorus in plays, rituals and other performances in ancient Greek city-states. Satama and Vahtikari show who typically performed in the chorus, what roles the chorus played and why their movement expression was important.

Since Antiquity proper, European art has repeatedly used references to Antiquity to justify different aesthetic solutions and the common features of entire styles. In the performing arts, Antiquity has been used to argue for particular structure of works as well as the representation of nudity on stage, and both the need to adhere to ancient principles and the desire to modernise the art of dance.

In The Significance of Antiquity for Art Dance, Hanna Järvinen focuses on how this relationship to Antiquity connects late 19th and early 20th century dance art with a broader interest in body culture, sport and ideas of natural movement. She shows how these themes were inextricably intertwined with the pseudoscientific theories of the time, in particular racist ideas about white supremacism and the healthy body as a prerequisite for the representation of a healthy and morally virtuous soul.

HJ

The Transgenerational Continuum of Ballet

The strength of ballet lies in its narrative of centuries of unbroken artistic development, which began in European courts in the 16th century. However, a closer look at the history of ballet reveals very different ways the art form has understood its content and purpose as part of a wider cultural and historical transformation. The texts in this section explore both the diverse history of ballet and its influence on art dance more broadly.

Hanna Järvinen’s extensive article A Cultural History of Ballet: Five Centuries of a European Art Form presents the main trends in ballet’s long history in the light of new dance research. Ballet expanded from the danced entertainment of European courts to a professional form with internationally known stars. In the 21st century, much of this history has been rewritten thanks to feminist and postcolonial scholars examining previously neglected forms of ballet.

Mikael Aaltonen’s article William Forsythe’s Postdramatic Ballet and Choreographic Installations explains the many ways in which William Forsythe, who started as a choreographer in the 1970s, has reformed contemporary ballet. Forsythe, who moves between ballet, dance theatre, contemporary art and contemporary dance, has reinvented himself many times. In the process, he has demonstrated the richness of ballet as an art form precisely through constant renewal.

Hanna Järvinen’s article Orientalism in Ballet explores the reasons behind ballet’s narratives exoticising Eastern otherness. Why the representation of otherness has been of interest to ballet’s makers? What has it allowed white artists to do? What has this Eurocentricity meant for ballet’s self-understanding?

Jukka O. Miettinen’s article The Long History of Orientalism explores the ways in which European dance art has both produced ideas about the mythical East and created links between very different performing arts traditions.

Focusing on one key work, Hanna Järvinen discusses the repercussions of Vaslav Nijinsky’s 1913 ballet The Rite of Spring. Considered a mythical modernist turning point in the history of dance, this ballet has inspired many dance makers to create their own interpretations. The Rite of Spring has accommodated both romanticised visions of primitive peoples and rigorous critiques of such narratives. It has functioned as a dramatic story and as a symbolic reference point linking new thinking in and about movement to a long history of previous versions.

HJ

Expressions of Dance Modernisms

A wide variety of expressions of modernisms developed in different forms of dance worldwide. In the West, modernisms extend from the canon of white modern dance to various forms of Afrodiasporic and Pan-African modern dance, left-wing revolutionary dance or dance in cabarets, and many new social dances. From the outset, these modern dances were highly transnational, interacting across national borders and genres as dancers travelled to tour and train. In addition, many artists worked in different environments, deliberately disregarding differences between “art” and “entertainment.”

In her extensive overview, Developments of Dance Modernisms from the 20th Century Onwards, Riikka Laakso traces the trajectories of modernist forms of dance in the West since the 20th century. The two centres of the modern dance canon, the German Ausdruckstanz that developed in the 1920s and the white US modern dance that gained strength in the 1930s, are here examined in the light of new research in the 21st century. Although Ausdruckstanz is the most famous new dance style in Weimar-era Germany, cabarets and films were important forums of modernist expression in dance. At the time, bodily expression was channelled in dance in many different ways. Improvisation was used to explore free movement as artists considered how movement related to music and space. Rudolf Laban’s movement choirs brought together amateurs and professionals, and he developed both theory of movement analysis and a system for recording movement, Labanotation. Mary Wigman’s often ecstatic dance and systematic improvisation-based pedagogy influenced modern dance globally, as she toured and founded schools in Europe and the United States. However, with the rise of National Socialism in Germany, the diversity of dance diminished and some forms of Ausdruckstanz were harnessed for (body) political purposes.

In contrast, the white modern dance that developed in the US in the 1930s emphasised movement’s form. Different dance techniques emerged to convey each choreographer’s personal movement language to the dancers – for example, the famous Graham technique. Indeed, Martha Graham is the most iconic representative of this white modern dance. Her work was characterised at times by psychoanalysis-inspired ambiguity, symbolism, mythological or nationalistic themes. Conversely, Doris Humphrey was interested in the relationship between the group and the individual, both in composition and as an expression of democratic values. She also developed a theory of choreography composed of exploration of rhythm, dynamics, design and motivation.

As canons were being constructed, not all dance forms were included. Revolutionary dance and the modern dance developed by Anna Sokolow were based on leftist values. Hanya Holm’s work shows how German dance influenced the development of modern dance in the US, and this did not suit the narrative of modern dance as an American invention. Johanna Laakkonen’s article Hellerau and Transnational Modern Dance explores international interaction through the pedagogy of the school founded by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze in Hellerau and its influence on the development of dance training. Despite its international significance, this heritage has been forgotten in history writing that emphasises a certain aesthetic or national narratives.

Despite facing oppression in the US, Black modern dancers also formed professional companies and toured widely. In her article Afrodiasporic and Pan-African Modern Dance, Hanna Väätäinen examines the impact of segregation on artists’ work, aesthetics of African American concert dance, and Afrodiasporic identities in dance. Dance offered an opportunity to advance equality and protest injustice. Various Afro-Caribbean influences fused with ballet and white modern dance techniques in new works and techniques developed by Alvin Ailey, Katherine Dunham and Pearl Primus, which helped the development of a new discipline, dance anthropology. In the 21st century, Pan-African modern dance forms include the technique developed by Germaine Acogny, which is founded on community and inclusion of all kinds of physicalities.

In dance art, the transition towards the postmodern era began in the 1950s. One factor in this development was dancer-choreographer Merce Cunningham’s rethinking of choreography. Riikka Laakso introduces this artist in her article, Merce Cunningham – 65 Years of Rethinking Choreography and Artistic Coexistence. She explores Cunningham’s chance-based methods for choreography and ideas on the independence and non-hierarchy of different art forms as elements of performance.

RL

Postmodernism in Dance (1960–1970)

This chapter deals with a period of intense changes in world politics. The 1960s were characterised by radical demands for reform in both society and the arts. Dance art moved into the postmodern era, here represented by various North American dance makers and phenomena and Japanese butoh. These new approaches sought to distance themselves from the dominant foundations of ballet and modern dance. Instead, dance was treated as a contemporary art form, a cultural language that could be consciously explored, deconstructed and reconstructed. Both a kinaesthetic exploration of movement principles and an interdisciplinary of arts were explored, dance makers employing different media and materials as components of choreographic performances. New York’s white dance avant-garde emphasised experimentation and representational critique, seeking to break away from both the movement’s mimetic relationship to reality and its connection to the body of the choreographic auteur. Choreography and dance performance could manifest as writing, as concept and task structures, on stage, in shared space, or spatially and site-specifically in public spaces. Meanwhile, new developments in Black dance drew on a strong sense of community, interdisciplinarity of arts, Afrodiasporic research and socio-political awareness. Japan’s first postmodern dance form was butoh, mixing styles, eras and cultures. Butoh was a creative fusion of both national tradition and international modern art that later gained international prominence on a range of European and American stages. In contrast, the different strategies and aims of white and Black dance led to parallel paths and a lack of convergence, a history of segregation that has only been critically examined by dance theorists and makers in the 2010s.

Kirsi Monni’s extensive article The Postmodern Spectrum – New Openings and Radical Redefinitions of Dance in the 1960s provides a background to the choreographic and art-theoretical development of postmodern dance and highlights its defining features and factors. In a new way, embodied perception, kinesthesia and improvisation take centre stage in the art of Erick Hawkins and Anna Halprin, among others. Deconstruction and systematic exploration of the structures of choreography and performance led to the development of choreographic concepts and task scores in works by Simone Forti and the Judson Dance Theater collective. Multidisciplinarity, materials and objects, elements of everyday movement and popular culture fused in Judson’s experimental performance evenings, which still echo in contemporary dance and multidisciplinary collaborations of the 21st century. White and Black postmodern dance received unequal attention; the article highlights Black postmodernists such as Blondell Cummings and Gus Solomons and discusses the differences in artistic starting points and aims of white and Black artists of the 1960s–80s. The last section looks at the art theoretical debate at the time and explores key concepts such as postmodernism, minimalism, metaphor and metonymy.

Two articles by Riikka Laakso discuss iconic postmodernists Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown. The first article, Yvonne Rainer and the Questioning of Choreographic Conventions, highlights Rainer’s miniature Trio A, which manifests a systematic critique of choreographic conventions, including hierarchy between movements, thematic development and dancing as “heroic” performance. Trisha Brown was constantly searching for choreographic structures that enabled new ways of moving and new realities. The second article, Trisha Brown – Choreography as a System that Makes Dance Happen, describes how Brown’s extensive career encompasses gravity-investigating works, choreographies as systematic development and “memorised improvisation” in works like her landmark piece Set and Reset (1983).

Mirva Mäkinen’s article The History and Characteristics of Contact Improvisation introduces the dance form based on improvisation and contact between dancers that originated in the 1970s. Contact improvisation incorporates elements of social dance, sports and martial arts as well as personal intimate experiences. Hanna Väätäinen’s article Community in Afrodiasporic Concert Dance explores the development of Black American dance, highlighting Afrodiasporic themes and pan-African roots behind its aesthetics, community and political goals. Through the artistic content of their work, Alvin Ailey and Dance Theatre of Harlem seek to create career opportunities for Black performers and engage members of their communities, as well as to empower African Americans through the concept of Black dance.

In Butoh Revolutionary Aesthetics and Influence on Contemporary Western Dance, Anna Thuring discusses the emergence and aesthetic characteristics of butoh. Butoh developed in Japan at the same time as the postmodern dance of the 1960s and 1970s in the United States, but it sprang from Japan’s own national cultural identity. It stemmed from a revolt against a commercialised aesthetic that superficially copied Western performing arts and, in particular, against Americanisation since the Second World War. Difficult to categorise, butoh is characterised by process orientation, open form, avoidance of straightforward narrative, anarchy, grotesqueness, playfulness, questioning of gender and the fusion of cultural elements at different levels. After Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, who developed butoh, subsequent generations of butoh artists integrated into the Western art scene as a sort of artistic nomads, operating from their bases and moving from them around the world according to work opportunities.

One starting point for characterising European and North American experimental dance and its aesthetic features in the 1970s and 1980s is to describe the techniques and approaches to dance practice. The section concludes with Working with Images as a Basis for New Dance Techniques by Riitta Pasanen-Willberg. She describes release and alignment methods, which are based on working with anatomical and kinaesthetic images, and on the dancer’s self-direction instead of teacher-driven and movement model-driven work. These methods lay the groundwork for choreography created through improvisation and have since expanded in various forms to become a typical methodological approach in contemporary dance.

KM

Innovators of European Dance in the 1980s

From the 1980s onwards, the historical developments in contemporary dance refracted like light through a prism into different aesthetics and ways of making dance. The experiments of the North American avant-garde of the 1960s and the issues raised in postmodern dance required updating dance’s relationship to the world and the audience, encouraging an interest in minimalist movement and different spaces and stages for dance. Many choreographers worked on movement with an increasing awareness of the means, aesthetics and starting points of theatre, performance art and music. Technological developments spread information and images more rapidly from one country to another and dance became more visible as part of (popular) culture. Conversely, elements of popular culture and references to it became established as part of contemporary dance. Institutional support extended beyond ballet, increasingly also to contemporary dance.

In the 1980s, the whole field of dance expanded and diversified. Increased funding for contemporary dance enabled not only long-term and professional work, but also large-scale performances and the emergence of bigger dance companies with higher public visibility. As examples of the diversity of the field, the chapter focuses on the work of three prominent artists in the European art dance scene of the 1980s. Of course, there are a number of other potential perspectives, such as the work of les ballets C de la B, founded by the Belgian Alain Platel, that collaborated with a wide range of artists and expanded the understanding of contemporary dance through practices and aesthetics. US dancer Carolyn Carlson used theatrical elements in her works and created a strong and original style employing lighting and decor. The work of the three European artists presented in this chapter serve as an example of how contemporary dance aesthetics and ways of making dance grew in very different directions in the 1980s.

Liisa Pentti’s article Pina Bausch – Historically Conscious and Radical Reformer of Dance Theatre explores the work of the iconic Pina Bausch as a developer of German dance theatre (Tanztheater). Bausch’s unprejudiced way of combining the means of dance and theatre – or problematising this interaction – created new dramaturgical and performative forms. Some characteristics of Bausch’s dance theatre include the postdramatic collage quality of the works, the dancers as creators of the material, the interest in everyday movement, the reflection on the relationship between audience and performer, the treatment of the human being and humanity, and the alternation of comedy and tragedy.

Aino Kukkonen’s article DV8 Physical Theatre as an Example of Norm Critical Dance Theatre approaches the outspoken dance theatre of the English company DV8, which questions social norms from gender roles to freedom of speech. In the 1980s, DV8, which criticised the elitism of contemporary dance, was particularly known for its themes related to gender and sexual diversity, which became increasingly visible in society during the period. Central to the group’s very physical dance theatre is the diversity of its performers and its collective way of working. The themes were approached in an everyday and direct way, with humour and irony. DV8 also made several dance films, which contributed to lowering the threshold to watching dance.

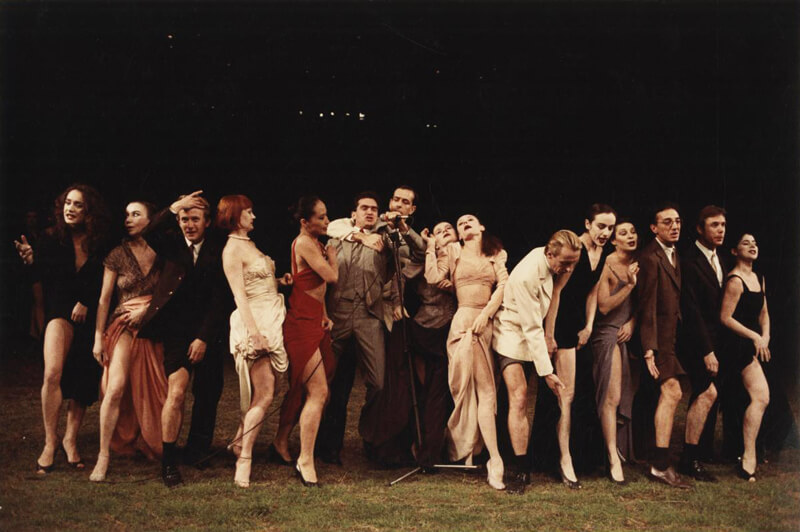

Belgian Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s works stood out in a European context that drew heavily on dance theatre. In her article Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker – Minimalist of European Dance Art, Liisa Pentti describes De Keersmaeker’s work as an abstraction constructed through movement and the body. Her early minimalist choreographies were based on music and in particular on analytical work with musical structures. From 1983, with the cult classic of dance, Rosas danst Rosas,De Keersmaeker began to introduce ideas from the US American Judson Dance Theater collective into the European contemporary dance scene. The choreography, based on simplified movement material, conveys meaning through repetition, subtle variations of simple movement and relations between bodies, movements and the space. In later productions, these elements evolved into multifaceted, rich choreographies of space and time.

RL

Multiplicity of Contemporary Dance

The closer we get to the present day, the more diverse dance art becomes. The aesthetic and stylistic features and changes in dance, in terms of languages of expression, no longer follow one another chronologically. Rather, contemporary dance is defined by the parallelism of many historical developments. In the 21st century, dance art is not a homogeneous field of art in terms of aesthetics, artistic aims, production conditions or starting points, but a heterogeneous field that is realised and defined in different frames of reference.

Since the 1990s, the diversification of contemporary dance has expanded thanks to higher education and research in dance and performance, digitalisation, increased funding and multidisciplinarity in artistic interchange. Increased awareness of dance phenomena around the world, made possible by internet platforms, and dance’s emerging relationship with current social, philosophical and art-theoretical debates, provide a basis for artists and researchers to continuously update their relationship with society and build new performance formats and interpretive frameworks for contemporary dance. Dance’s evolving self-understanding, methodological diversity and creative collaboration between artistic teams, dancers and choreographers form the creative landscape of contemporary dance. Creators and works define what dance and choreography are or could be, depending on the frame of reference, stage or operational environment.

The Finnish edition of this textbook, published in 2022, presented selected perspectives on contemporary dance from the 1990s and 2000s. These cover only a fraction of the broad field of contemporary dance and the authors of diverse dance and dance-related performing arts. In addition to introducing the other articles of this chapter, Kirsi Monni’s article Contemporary Dance Since the 1990s – a Brief Overview discusses some of the artistic and sociopolitical ideas that have influenced the field of contemporary dance.

Since the 1990s, contemporary dance practitioners have become increasingly interested in how the meanings of dance and choreography are constructed in relation to broader conceptual paradigms and discourses. Themes in contemporary dance have included the exploration of the performativity and politicisation of embodiment and identity; collective working methods in artistic processes; and the rise to prominence of Black aesthetics and avant-garde.

Moving between the public and the private, dance works have addressed the multiplicity of sexuality and gender, as well as a broader notion of human existence permeated by ecological and environmental interconnectedness. Contemporary dance works can be easily situated within the interpretive frameworks of choreography, performance art or visual art contexts, and can take the form of live performances on stage, in a museum, gallery, public space, virtual reality, online, or all of these in different versions of the work. The “internet aesthetic” is influencing dramaturgies in different ways, not least through the opportunities created by dance film and virtual technologies. The 21st century has also seen the rise and appreciation of social choreography and community art, a more visible role for persons with disabilities in dance art, and growing critique of body normativity. The broad field of performance studies, dance research and artistic research enables theorists and practitioners in both education and the arts to question, explore and enrich dance’s ability to connect with the world as a vibrant contemporary art.

The articles in this section, listed below, discuss not only the factors and phenomena that have significantly influenced contemporary dance aesthetics, but also the expanding field of dance art.

In order to further enrich the contents and practices associated with the concept of dance art in the coming years, this textbook will require updating with new perspectives on dance in the 21st century.

Kirsi Monni: Contemporary Dance Since the 1990s – a Brief Overview

Kirsi Monni: The Embodied Practice of Perception as a Starting Point for Dance – Deborah Hay

Thomas De Frantz: Black Sensibilities – Contemporary Dance of an African Diaspora

Kirsi Monni: Discursive Practices in Choreography – Jérôme Bel, Vera Mantero and Xavier Le Roy

Riikka Laakso: La Ribot – Embodied Dialogues

Hanna Väätäinen: Ableism in Dance and Disabled Dancers

Hanna Pajala-Assefa: Dance film – an Alliance of Dance and Moving Image

Ari Tenhula: Dance Art and the Internet Age – What is the New Aesthetics of Dance?

Hanna Pajala-Assefa: Dance and Technology – New Stages for Mediated Bodies

Simo Kellokumpu: Artist, Researcher and the Challenge of Writing

KM

Contributors

Kirsi Monni

Kirsi Monni (Doctor of Art in Dance, 2004) is Professor of Choreography at the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki. She has worked extensively in the field of dance as a choreographer, dancer, researcher, lecturer, curator and in various positions of trust since the 1980s. Her own research deals with historical, ontological and theoretical questions in dance art and choreography. Monni is one of the founders of the Zodiak – Centre for New Dance and was involved in its development for two decades before accepting a professorship at the Theatre Academy in 2009.

Riikka Laakso

Riikka Laakso works in the field of dance as a writer, lecturer and dramaturg. She holds a PhD in performing arts from the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (2016) and teaches theatre analysis and dance history at the Institut del Teatre de Barcelona. Laakso has collaborated with Zodiak – Centre for New Dance, the Theatre Academy, Helsinki and choreographer Sanna Kekäläinen, and is responsible for the dramaturgy of works by choreographer Marina Mascarelli.

Hanna Järvinen

Hanna Järvinen a university lecturer and department head at the Performing Arts Research Centre of the Theatre Academy, docent in dance history at the University of Turku, and Honorary Visiting Research Fellow at De Montfort University in Leicester. She has researched authorship and genius as well as the performing arts canon and the use of power in the light of feminist and postcolonial research traditions. She is also interested in issues of modernity and materiality at the intersection of performance and performing arts and dance orcid.org/0000-0001-9081-9906.