I cannot think of anything else in my life where there is so much unlearning and learning happening at the same time.

[1]

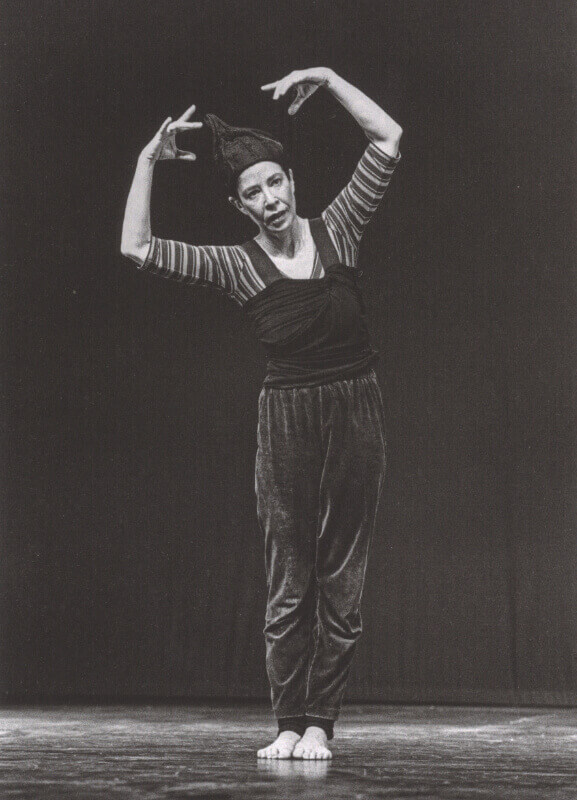

American choreographer-writer Deborah Hay (b. 1941) belongs to the postmodern dance generation of the 1960s, but her internationally influential artistic career is primarily set in the 21st century. Hay began her career with the Judson Dance Theater collective in early 1960s New York and as a dancer with the Merce Cunningham Company on a world tour in 1964. In the 1970s, Hay broke away from the performing arts framework and worked in Vermont, mainly with nonprofessionals, creating Ten Circle Dances, performed without an audience and sponsored and produced mainly by museums and art galleries.[2] Hay’s first book Moving through the Universe in Bare Feet (1975) describes these dances.

In 1976, Hay moved to Austin, Texas, where the Deborah Hay Dance Company, founded in 1980 to support Hay’s work, continues to operate. From the 1970s to the 1990s, Hay worked primarily with untrained dancers and continued her intensive research into the practices of creating, communicating, and transmitting choreography. During those years, she developed a series of “playing awake” exercises that envelop the performer in multiple levels of body-mind awareness at the same time. In Austin, Hay ran large annual four-month workshops for dancers, culminating in public performances by the groups. From these group works, Hay modified her solo dances of the time. Her second book Lamb at the Altar: The Story of a Dance (1994) describes these processes.

At the turn of the millennium, Hay created solo works: The Man Who Grew Common in Wisdom, Voilà, The Other Side of O, Fire, Boom Boom Boom, Beauty, Music, The Ridge, Room and No Time to Fly. She performed these works around the world and transmitted them to other dancers, applying a method she developed based on the embodied practice of perception and written choreographic scores. Hay’s third book, My Body, The Buddhist (2000), describes her approach to dance and the reflections on life’s most important lessons that unfold through the body. Hay’s fourth book, Using the Sky (2016), provides a rich account of Hay’s choreographic process from 2003–2014, including script versions of the NYC Bessie Award-winning group work The Match (2004), six dancers’ If I Sing to You (2008) and solo No Time to Fly (2010).

In 2001, Hay began to apply the approach and method she had previously developed, both in her solo work and with untrained dancers, to work with experienced dancer-choreographers. She continued to work in the professional dance field ever since, working extensively with large dance companies, festivals and individual dancers. In addition, Hay has carried out the Solo Performance Commissioning Project 14 times, in which a total of more than 200 dancers have created their own adaptations of Hay’s solo works.[3]

Hay’s importance as a thinker and developer of the approaches and methods of contemporary dance and as an original choreographer has been widely recognised in the 21st century, and she has received numerous awards in both the United States and Europe. Hay has been awarded an honorary Doctorate of Arts by the Theatre Academy (currently part of the University of the Arts Helsinki) in 2009 and the Doris Duke Performing Artists Award in 2012. Various festivals and production companies, such as Tanz im August in Berlin and Barcelona’s Mercat de les Flors, as well as museums such as MoMA in New York, have produced extensive retrospectives of her work. In 2013, Hay was invited to be the first artist of The Forsythe Company’s digital choreographic research project, Motion Bank, and in 2012 a documentary film about her work was released, Turn Your F*^king Head. Hay has visited Finland on several occasions as a choreographer and guest choreographer at Zodiak, the Side Step Festival and Helsinki Festival, as well as teaching workshops.

Practice as Performance and Performance as Perception Practice

Hay’s influences can be seen to stem from East Asian philosophies as well as post-dramatic, postmodern art. The role and importance of the actual situation and bodily perception, as well as reflection on events in the mind, are fundamental to Buddhist and Taoist philosophy, for example. After the Second World War, these influences were increasingly seen in Western art, which sought to find a “new beginning” in both content and method. In dance, Erick Hawkins had emphasised the experience of movement, perception and nonrepresentational existence as the starting point for dance at the turn of the 1950s and 1960s but retained the idea of choreography based on a technical and reproducible movement vocabulary. (see The Turn to the Bodily Perception in Dance – Erick Hawkins)

In contrast to Hawkins, Hay can be said to have radicalised what was then an early development of the “turn to perception”. Working with untrained dancers, Hay was looking for a starting point and a way of thinking about dance that was not based on the mastery of a unified movement vocabulary or aesthetics, but which nevertheless offered the opportunity to become interested in movement and dance in an artistic sense, choreographically.

The working method developed by Hay became radical in terms of dance, choreography and the redefinition of performance and performing. In Hay’s thinking, dance is not based on what is performed, on the choreography of certain forms of movements or on their predetermined performance. Instead, Hay’s dance ontology is centred on the bodily perception of the unique eventfulness of the “now” moment and the dynamic interaction with the situation, of time, space, others, self and the choreography.

Our consciousness tends to “fall asleep” and become fixated on the thoughts and images that come to mind and on the “pre-choreographed”, habitual body, thus narrowing open perception of the situation. To break free from automated behaviour our consciousness must therefore be constantly reawakened by re-perceiving the actuality of each moment. For Hay, the actuality of the now moment is perceived as a change in space-time and the central manifestation of change is the dancer’s movement. The perception of eventfulness, or the actuality of the now moment, is also not a definitively attainable thing or entity, and can only be approached humbly from the perspective of practice. Hay’s choreographies intertwine both the methodical practice of bodily perception and the choreographic score as a path of impossible tasks. This ensures that the dancers do not become fixated on the illusion of permanence and do not take themselves too seriously in the face of the existential “cosmic joke” into which humans are thrown.[4] Instead of finding the final answer or doing the right thing, the dancer can only continuously ask ‘what if all the cells of my body could perceive the originality and uniqueness of time and space, self and others happening right now’.

For Hay, dance seems to be a kind of life-affirming survival strategy, anchored in bodily existence, in the recognition of the incomprehensibility and fathomlessness of the universe. Choreography, in turn, functions as an artistic expression and composition that frames dance, bringing – or, as Hay says, “tricking” – the dancer into the paradox and mystery of life, in which this survival strategy can be practised in an artistic form that can be shared with others. This perspective helps to explain Hay’s idea that performance and performing are not a repetition of something that already exists, but a practice of one’s own perception, a constant awakening of consciousness; in this sense performance in the rehearsal space is no different from the exercise of bodily perception with the audience on stage.

The Artistic Process and Performing

While working on her own solo pieces, Hay developed both the premise of dance as a practice of embodied perception and the open-ended questions and practices that characterise each piece. Because our perception is intimately connected to the learned, the familiar and the conventional, Hay approached movement from an unconventional direction, thinking of the body as billions of cells that perceive the “now” moment of time, space, self and environment as a continuous, unending process. For Hay, working with this notion is a continuous recognition and “unlearning” of the habitual and pre-choreographed body and movement; at the same time it is an endless bodily learning. In addition to the practice of bodily perception, choreographic working process contain specific questions or sentences that shape the world of the work and a multilayered written score with which the dancer is in creative relationship as they dance and perform.

In her book My Body, The Buddhist Hay lists the specific practices from 1970–1999. Hay’s thinking is linguistically very precise, and the practices need to be written in their exact form to do them justice.

The exercises have included:

- 1980–1985: The whole body at once is a teacher.

- 1985: I imagine every cell in my body invites being seen perceiving no movement wrong, out of place, or out of character.

- 1995: I imagine my whole body at once has the potential to dialogue with all there is.

- 1991–1992: Every cell in my body invites being seen living and dying at once. Wherever I am dying is. What if dying is movement in communion with all there is? What is impermanence is steadily transforming present? Seeing impermanence requires admitting that nothing is forever. I am the impermanence I see.[5]

The questions posed by Hay are inherently paradoxical and impossible to answer. Rather, they are a way of “playing awake”, of practising detachment from the conventions of thought and action while the sensual and perceptive embodiment is the teacher. Hay also emphasises the two-way nature of perception, the interplay with both the environment and one’s own embodied events, making the practice especially a practice of performer and performing. The performer also observes while being observed and perceiving the actuality of the situation opens up the possibilities for movement.

- 1986: I invite being seen whole and changing. You remind me of my wholeness changing.

- 1991: Every cell in my body invites being seen just so.

- 1988: I imagine every cell in my body has the potential to perceive movement as nourishment which supports movement which is nourishment, etc. etc.[6]

Hay’s choreographic scores are multilayered, containing precise temporal, spatial and functional definitions and descriptions, yet leaving the dancer free to interpret and realise them in each performance. The dancers’ work with time and space and the multilayered score – to which they can relate creatively during the performance – directs the viewer’s attention to the dancers themselves. Hay’s aim is to direct the viewer’s attention to the moving person rather than to the movements they make. As Hay says: “Dancers are individuals, and there is no one ‘right’ way to do any movement.”[7]

Hay’s working method is demanding and requires a period of at least three months, during which the dancers perform an interpretation of the choreography every day before the first performance open to the public. This allows the dances to develop into very personal, independent adaptations of the choreography. Hay has therefore emphasised that she prefers to work with dancers who are also choreographers and who have developed skills to perceive time and space. In the pr-material for the 2008 Helsinki version of If I Sing to You, Hay outlined the qualities she particularly values in a dancer: the ability to perceive time and space, the ability to be brave and take risks, the ability to collaborate and interplay with fellow dancers on stage and to relate freely with the audience during the performance.[8]

Dancer Vera Nevanlinna has worked with Hay in several international projects. She describes Hay’s way of working as challenging, interesting and rewarding for the dancer.

We learned the choreography in two days at the beginning of the rehearsals. After that we performed it twice a day, every day. That means there were about 60 performances before the premiere. Usually it’s the other way around; the choreography could be completed only a few days before the premiere. Deborah’s way of working can grow a multilayered memory and a historical dimension in relation to the choreography and fellow dancers. The boundaries of choreography are stretched and experimented with so that in the actual performance, the dancer’s range of action is quite broad, while the detailed figure and form of the choreography is maintained.

[9]

Writing, Choreography and Adaptations of Works

All my work is ultimately but a question of language.

[10]

When asked how Hay identifies her choreography when it cannot be identified through set movement forms, she emphasises the way the dancer chooses to be in relation to the moment. For Hay, these choices can be seen on stage. “I recognize my choreography when I see a dancer’s self-regulated transcendence of his/her choreographed body within a movement sequence that distinguishes one dance from another.”[11] The precision and conciseness of the phrase reflects Hay’s relationship with language. The attempt to define the specificity of her choreography, and the awareness that language is the only available means of doing so and ultimately of documenting and preserving her choreography, leads to Hay’s idea that everything she does to define her work is always ultimately about language.[12]

In Hay’s practice, everyday dance in the studio goes hand in hand with writing. Hay explores how writing serves both to document the choreography and to communicate the choreography to the dancer. Hay never demonstrates how a dance should be done, instead she works out the choreographic score in a lengthy process in the studio before working with the dancers. The score provides the structure of the piece and the world of dance for the dancer to work with; then Hay teaches the method for the dancer to be in creative relationship with it. Both solo and group pieces are based on this kind of score work. This ensures that each version of the group performance is different from the other and may contain some cultural and local characteristics. For example, Hay explains that the American version of O, O (2006) had a somewhat simple, even minimalist character, while the French version was theatrical and exaggeratedly costumed.[13]

Hay’s choreographic scores have been published in books such as Using the Sky (2015) and Re-Perspective Deborah Hay (2019), which include commentaries, drawings and other sketches. Some scores are close to fiction, others to plays in their form, but they are all united by a highly elaborate linguistic precision, a continuity of discontinuity and unresolved tasks like kōan exercises in Zen, where aspects of humour and playfulness are often present.

Hay’s embodied practice of perception can be read in choreographic scores, where what is constant is the continuity of change and self-reflection; the choreographic score builds and disassembles, creates a situation to be detached from, gives an image to be abandoned and to be sincere without taking oneself too seriously.

Excerpt from the choreographic score of No Time to Fly

At center stage I reverse direction and turn in place while lifting my arms instrumentally, to signify the construction and architecture of a HOLY SITE. At the same time my shoes lightly tap the floor under me as if to imply the sporadic thwacks of hammer striking in the distance.

Note: I am A HOLY SITE and to perform as such requires the catastrophic loss of how I otherwise perceive myself.

A HOLY SITE is completed the moment my hands or fingertips touch overhead. I open my mouth and hear A HOLY SONG rise up out of me.

Note: I call what I hear A HOLY SONG and notice the feedback from my whole body as it yields to that direction.

Unable to sustain itself, A HOLY SITE collapses. My hands, still touching, drop before my eyes. I contemplate the symbolism of the gestural demise.

Resourcing whatever bit of prior exposure to a fake American Indian ritual dance, primarily Hollywood westerns, I discharge those bits as best as I can while rhythmlessly bouncing to beating drums that only I can hear.

My fake American Indian ritual collapses. I rebuild A HOLY SITE, using the sound of my tapping feet to symbolize the sound of distant hammering. I travel in fading light.

Light returns and I am tiptoeing, not wanting to disrupt the space already created – a task I hold in high regard. I experience space parting, with little disturbance, hoping that the audience will see this too, before arriving somewhere that is not center stage. My actions are obvious.

When I imagine the stage still, a return to the fake American Indian ritual dance occurs. I may be the only person in the world to realize this, yet, punctuated by beating drums that only I can hear, I bounce rhythmlessly.

I lift and point my right index finger in the air and, speaking with an accent say, “Strictly speaking I have never been anywhere” (Beckett, 2000. P.25).

With my finger still in the air, leave time for the Beckett quote to sink in.

Note: The quote’s impact on my body is mind-boggling.

My right hand lowers as I hum as exaggerated departure from the tune “Oh, they don’t wear pants in the sunny side of France. But they do wear grass to cover up their ass.” I may not even hum or I stop and start. My perception of joy and sorrow guides the singing. The lifetime of my singing is how long it takes for my hand to lower while crossing the stage without anyone knowing. My standard for “lower” is my own.

Note: My hand can be a trap. I do not fixate on it. Deliberately hiding its function in determining my movement.[14]

Although Hay does not define the language of movement and vocabulary, the choreographic scores and the method of attentiveness do create some aesthetic and stylistic features. Hay describes wanting “to choreograph a spoken language that would inspire a shift in dance away from the illustrative body, despite its intense appeal to dancers and audiences alike, to a non-representational body.”[15] In the dancer’s work, the semantic linguistic level, the images and instructions evoked by the words, and the somatic bodily level interact creatively with each other. The dance appears to the viewer as simultaneously non-illustratively abstract and functionally concrete. It may contain gestures, cues and hints, words, sounds, singing, memories and places of meaning, but never in an unambiguously illustrative way. The attempt to hold on to the observation of a unique event also means that the dancer breaks away from the habitual and instinctive sequencing and continuity of movement of the pre-choreographed body. For Hay, this means that space and time can expand forever, and that beyond one’s own limited experiences, there are endless dances waiting to be performed.[16]

Excerpt from the score of The Match:

Fi, Fra, Chas: Cross to a new location performing smartly executed movement, based on the six-minute rhythmic dance established by Cathy. Fiona performs center stage.

Note: Smartly executed movement is not driven by inner rhythm, a sense of flow, or. A history of training; movement that does not feel personally gratifying.

Fra, Fi, Chas: Like three matches extinguished, movement stops.

Chas: Restart and exit, performing smartly executed movement.

Fi, Fra: Proceed to the next location, performing instances of weightless, lyrical spiraling movements not unlike smoke, but not like it either. Softly hum an intermittent spontaneous love song.

[17]

Particularly in group choreographies, such as the Cullberg ballet’s Figure a Sea (2015), a certain landscape-like quality of Hay’s choreographies is evident. The use of stage space is reminiscent of a landscape of intersecting paths rather than a mathematically structured space. Rather than working with a three-dimensional body, Hay poses perceptual questions to a nonhierarchical “cellular body.”[18] Instead of a geometric spatial structure, the choreography creates a topological moving landscape on stage, where we observe nonlinear and unpredictably progressive choreographic structures. The force that holds the choreography together is not located in the narratives of movements or stories but in a dialogical relationship with the choreographic score and the perception of the moment.

References to a landscape can be also read in the performance guidelines for Figure a Sea. The ensemble of 21 dancers in the work forms an unpredictable and “undulating” layer of movement, characterised by an active and contemplative attentiveness.[19]

Excerpt from the Figure a Sea performance guidelines:

A general rule of your movements derive from the perception of yourself as a particle in a sea – not a whole particle but a fraction thereof. (In other words, there is no seaweed imagery onstage.) You are a sea of potentiality where here and gone are nearly indistinguishable.

Without rhythm, or not rhythmic for long, your movement through space displaces the sea onstage.

Pause is a movement that silently suspends your activity.

[20]

Another recognisable and aesthetically defining feature is the fact that Hay’s choreographies have very little composed music. When asked why, Hay replies that she finds any additional rhythm distracting. “I feel that movement itself is music or I suggest that movement could be read as a musical event. This is how all movement becomes interesting, fascinating and enchanting. Instead of music I often use voice when dancing. The sound and the voice are sending the movement out to the space.”[21]

Hay’s relationship with choreography and its transmission to the dancers through the score as well as a certain methodology, allow for different adaptations of the same works, but also for their transformation from group pieces to solos or vice versa. The process is similar to transcriptions of classical music, for example, where an orchestral work is arranged for a solo instrument or a group of instruments. For example, the group work The Match (2004) was adapted into the solo The Ridge (2004) for theSolo Performance Commissioning Project. In 2011, three dancers, Jeanine Durning, Juliette Mapp and Ros Warby, made their own arrangements of Hay’s solo No Time to Fly, and then made a trio adaptation of the work under the title As Holy Sites Go (2012). As part of the Motion Bank research project, these adaptations were digitally recorded as a series of overlapping performance versions, from which Hay choreographed a score for Figure a Sea for 21 dancers (2015). In Hay’s works both the method and the score give a possibility for interpretation and variation, as in If I Sing to You, where the performers decide on each performance night whether to perform the piece in the assumed masculine or feminine costumes. There can also be considerable variation between different performance versions of the work. This practice is common in theatre, where different versions of plays are often adapted and directed, but less common in contemporary dance. Flexibility also crosses artistic disciplines. For example, the theatre collective The Rude Mechs adapted The Match choreography for the theatre stage as The Match-Play in 2005.[22]

Hay’s practice and relationship to choreography emphasise the internal mobility and dynamics of choreography rather than fixed structures, but also the notion of the self as an unattached identity. The roles of dancer and choreographer and the notion of authorship have expanded and transformed, as has the definition of the choreographic work. In Hay’s case, the work cannot be defined as a compositional treatment of movement, but as an event of unique interpretation of a choreographic score.

Hay brought the practice of percpetion to the field of professional dance in the early 2000s, when contemporary dance began to recognise the problematic nature of its often generic movement language. There was a call for more open approaches to choreography, recognition of the creative role and individuality of the dancer, and the possibility of exploring the relationship between performance themes and expressive language without a conventionally preset aesthetic of movement or choreography. Hay’s premise of individual embodied perception has since become a widely known and relevant part of the artistic tools used to dismantle the homogenising assumptions of contemporary dance. In the 2020s, it is now typical that dancers work on performance scores and various perceptual tasks in a more or less collaborative and collective way during the process of creating choreography. Among the various contemporary dance practitioners, Hay’s work continues to be seen as exceptionally demanding and radical in its relationship to the premise of the choreographic work, dance and performance. In 2022, Hay herself is still practising dance and creating choreography, in her 80s.

- 1999: What if every cell in my body at once had the potential to locate and choose the oxygen it needs to keep my fire burning?[23]

Notes

1 Deborah Hay describes her relationship with dance in her website https://dhdcblog.blogspot.com, accessed on 2.8.2022.

2 Hay’s first book, Moving through the Universe in Bare Feet (Swallow Press, 1975) describes the starting points and processes of these dances.

3 The Solo Performance Commissioning project is a workshop during which Hay taught one of her solo choreographies and approaches to dance to the dancers participating in the project. The dancers committed to at least three months of daily practice before the public performance of their own adaptation of the choreography. The performance contract also included recording in a programme note all the supporters of the performance, including public and private sponsors, large and small. Monni 2004.

4 Born in 1941, at the age of 79, Hay explains her relationship to dance in 2020 on her website: “To survive as a dancer with less and less physical attributes to rely on, I experiment by applying different lenses to how I see while dancing. This supports my body’s potential to engage dynamically with resources outside of myself for inspiration and authorship. After years of incrementally increasing the field from which to unravel this dance, I find a cosmic joke, unfathomable yet unequivocally life-affirming. How I may see our universe, acknowledging its infinitude as I dance, is my survival.” https://dhdcblog.blogspot.com Accessed on 3.8.2022.

5 Hay 1997, 103–104.

6 Hay 1997, 103.

7 Monni 2008. Artist of the Week: an interview with Deborah Hay on 8.4.2008. Published on the Zodiak – New Dance Centre website in 2008. Monni private archive.

8 Monni 2008.

9 Monni 2008.

10 Hay in Katsiki & Pichaud 2019, 95.

11 Hay in Katsiki & Pichaud 2019, 95.

12 Katsiki & Pichaud 2019, 95.

13 Monni 2008.

14 Hay 2015, 115–117.

15 Hay 2015, 1.

16 Hay 2015, 106.

17 The Match score was not completed in this form when it was first performed in 2004. Hay has completed it on the basis of a performance recording. The acronyms refer to the original performers, who were Wally Cardona, Mark Lorimer, Chrysa Parkinson and Ros Warby. Hay 2015, 28, 33, excerpt from page 36.

18 Hay in Foster (ed.) 2019, 120–121.

19 “The combined active and contemplative nature of your attention is your finest contribution to the choreography and performance of Figure a Sea.” Foster 2019, 32.

20 Foster (ed.) 2019, 33.

21 Monni 2008.

22 The New York Times website https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/09/arts/dance/review-deborah-hays-match-play-fuses-dance-and-theater.html, Accessed on12.8.2022.

23 Hay 1997, 104.

Literature

Foster, Susan. 2019. “By Way of Introduction.” In Susan Foster, ed. Re-Perspective Deborah Hay. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Hay, Deborah. 1975. Moving through the Universe in Bare Feet: Ten Circle Dances for Everybody. Chicago: Swallow Press.

Hay, Deborah. 1994. Lamb at the Altar: The Story of a Dance, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Hay, Deborah. 1997. My Body, The Buddhist. Hanover & London: Wesleyan University Press.

Hay, Deborah. 2016. Using the Sky: A Dance. London & New York: Routledge.

Katsiki, Myrto & Pichaud, Laurent. 2019. “Works 2006–2002.” In Susan Foster, ed. Re-Perspective Deborah Hay. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Monni, Kirsi. 2004. Documenting The North Door Helsinki 2003 and The Ridge The Solo Performance Commissioning Project, Findhorn. Monni private archive.

Monni, Kirsi. 2008. Artist of the Week: an interview with Deborah Hay on 8.4.2008. Interview. Published on the Zodiak – Centre for New Dance website in 2008. zodiak.fi. Monni private archive.

Monni, Kirsi. 2019. “I am the Impermanence I see.” In Susan Foster, ed. Re-Perspective Deborah Hay. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Seibert, Brian. 2015. Review: Deborah Hay’s “Match-Play” Fuses Dance and Theatre. The New York Times. 8.10.2015. Accessed on 12.8.2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/09/arts/dance/review-deborah-hays-match-play-fuses-dance-and-theater.html

Contributor

Kirsi Monni

Kirsi Monni (Doctor of Art in Dance, 2004) is Professor of Choreography at the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki. She has worked extensively in the field of dance as a choreographer, dancer, researcher, lecturer, curator and in various positions of trust since the 1980s. Her own research deals with historical, ontological and theoretical questions in dance art and choreography. Monni is one of the founders of the Zodiak – Centre for New Dance and was involved in its development for two decades before accepting a professorship at the Theatre Academy in 2009.