The Europeanness of European art dance is construed through references to the common and the shared. In the traditions of ballet on the one hand, and in various forms of bodily representation and other performing arts on the other, references to ‘Antiquity’ have always been a way of placing contemporary art within a historical continuum, set somewhere between the two millennia from the city-states of Greece (from 1200 BCE) to the destruction of the Roman Empire (c. 600 CE). In other words, because ‘Antiquity’ is itself so vaguely defined, over time a wide range of ideals – including contradictory ones – have been associated with it. These ideals are often referred to as ‘classical,’ after the French 18th-century style.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Antiquity meant a Eurocentric past, intuitively understood and inherently better than the present. Even today, Antiquity is often presented counterfactually as a kind of ‘first Europeanism,’ whereby the cultural and aesthetic diversity of Antiquity is simplified and normalised in a Eurocentric fashion, for example by representing ancient people as white, as they had been represented in the 19th century.[1]

In dance textbooks, Antiquity is most associated with Isadora Duncan (1877–1927), designated as a trailblazer of modern dance. Duncan claimed that by identifying with the representations of dance in ancient art and European classicism, she was able to feel the meaning of Antiquity in her own body and thus mystically return to the ancient people’s understanding of dance.[2] The art of Duncan and the other American free form dancer who preceded her, Loïe Fuller, is often seen as the impetus for the emergence of a new kind of free or modern dance which, as the name suggests, ‘liberated’ women dancers from the stranglehold of corsets and ballet shoes.

In the light of more recent research, this rhetoric of ‘American modern dance’ is questionable to say the least. It creatively overlooks both the role of Antiquity in the history of European art dance and the performing arts, the diversity of dance forms performed on European stages and, more generally, the ways that Euro-American body culture entangled with eugenics and white supremacism. [3] Associating Duncan with the women’s rights movement is also flawed. Many early feminists were highly fashionable women, whereas male doctors concerned with the falling birth rate of the upper classes attacked the corset, as for these men it signified the demands for gender equality by women increasingly present in public life and working outside of the home.[4] As several feminist dance scholars have pointed out, Duncan’s views about women and femininity were quite conservative.[5]

Isadora Duncan’s Many Sources

Text and image sources from Antiquity that described dancing were focal for the self-understanding of European art dance. Lucian’s essay on dancing[6] inspired John Weaver’s early 18th-century writings and in 1830, Carlo Blasis similarly began his dance history with ancient Greece, referring to ancient reliefs as an excellent model for choreography.[7] In the 19th century, ancient dances also fascinated artists and pedagogues interested in reconstructions of old social dances. For example, Gustave Desrat, in his Dictionnaire de la Danse published in 1895, mentions numerous dances of various types from Greek and Roman sources.[8] The following year, the French composer Maurice Emmanuel published a 300-page book on movements in ancient Greek dances. With texts and images, Emmanuel sought to prove that the postures of ancient dances corresponded to the movements of ballet and that the French art dance of his day was thus on a continuum from Antiquity to the present.[9]

As Rosemary Barrow, Samuel Dorf, Sarah Gutsche-Miller and others have shown, themes from Antiquity were an entire genre in the performing arts. This was the performance genre of Isadora Duncan, who began her career in 1898, and other early 20th-century free dancers.[10] Duncan’s interest in Antiquity did not begin with museum sources: she and her siblings had studied Delsartism. Named after the Frenchman François Delsarte, this method of teaching rhetoric had become particularly popular in the North American temperance movement. Developed by Delsarte’s American students Steele MacKaye and Genevieve Stebbins, Delsartism conveyed emotion by reproducing gestures from ancient statues. Duncan’s ideas about dance as an expression of emotions and ideas were largely inherited from Delsartism.[11]

This also means that Duncan’s Antiquity was a product of the pseudoscientific racism of her day. As Ann Daly has pointed out, ‘Duncan’s construction of a “Natural” body did indeed imply a race and class hierarchy.’[12] Duncan’s United States of America did not include Indigenous peoples, and certainly not the descendants of Black slaves. The body that re-danced Antiquity had to demonstrate its moral and spiritual superiority through physical fitness and harmony as well as the ‘naturalness’ of its movements. This natural body, however, was trained to be graceful, supple, harmonious, and thus morally acceptable (even in the nude). The union of aesthetic and moral values meant that the natural body was a white, young, slim, fit and able body.

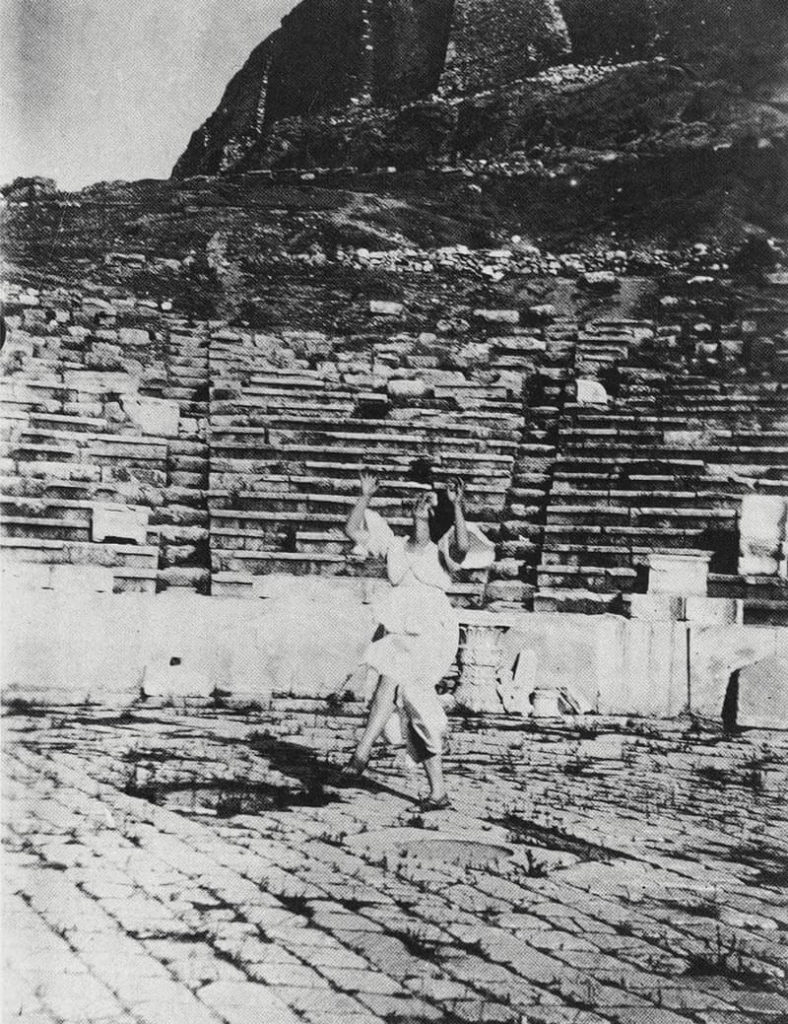

The imagery favoured by the early representatives of free form dance may serve as an example of the ambiguous ‘modernity’ of this dance and of the new relevance Antiquity acquired in these visual representations. Photographs of these late 19th and early 20th-century dancers are very often taken either in sunny meadows or amidst ancient ruins, or at least in surroundings that suggest such settings. The ambiguity of the word ‘modern’ is best illustrated by how it does not conjure in one’s mind images of alpine landscapes, green meadows or the Acropolis, but rather the metropolis, railways and rapid technological development. Dance was mainly performed where its audiences resided: on metropolitan stages lit with electricity or in the urban living rooms of wealthy patrons. Images illustrating early ‘modern dance’ are therefore not documentary in nature. Rather, they illustrate the ideology these dancers used to market their dances as a countermeasure tourban modernity. This ideology, in turn, was often founded on fears of the degenerative impact of modern life – ideas of biological decline threatening Europe, as exemplified by contemporary art.

Degeneration

Degeneration was a conservative theory of culture often associated with Maximilien Nordau’s eponymous 1892 book, and the cultural policies of the National Socialists of the Third Reich in the 1930s. The theory was based on fears of urbanisation and the mass behaviour of the lower social classes proposed during the Enlightenment, as well as the broader conceptual apparatus of pseudoscientific racism that followed the Enlightenment. The individual, culture, and nation were seen as biological organisms that could regress to a simpler and ‘inferior’ state because of evil influences or lack of discipline. A proof of the validity of this theory was the European colonialist rule in regions that in Antiquity had been dominated by local civilisations. The theory was directed at controlling modern art: Nordau for example, argued that impressionism demonstrated a physical fault in the painters’ eyes. Sexual ‘perversions,’ mental illness, and crime were all symptoms of degeneration, which would result in social ‘problems’ such as feminism and the labour movement.

This nostalgic return to classicism, a style that repurposed features of ancient Greek and Roman art, proposed a dynamic and holistic solution to social problems. Antiquity offered truths that were considered universal, or at least legitimised views about hopes and fears for the future. The Roman Empire served as a model for a new, middle-class imperialism, from which fascism developed after the First World War. These political ideologies gave a new emphasis to the disciplined training of the individual body in the service of the nation and the race.[13]

In the body culture of the time, dance closely related not only to theatre and rhetoric (as in Delsartism), but also to sport, especially gymnastics, and to new beliefs in healthy ‘natural’ living. Naturism (nudism) had justified non-sexual nudity, whereas movements related to hiking, allotment gardens and garden cities all justified a newfound connection to nature. Events imitating ancient Greek sporting competitions had been held from the 1870s onwards. Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic Committee in 1894, which organised the first modern Olympic Games in Athens two years later. Ancient gymnastics also served as a model for the new sport that has come to be known as bodybuilding: for example, Eugen Sandow often appeared in the role of Hercules. According to pseudoscientific racism and other ‘sciences’ justifying imperialism, the body in its ‘natural state’ – without the trappings of urban fashion – revealed its health; furthermore, the naked body always told the truth about the spiritual and moral powers of the soul.[14] No wonder, then, that the same association between ‘perfect’ bodies of Antiquity, health and whiteness is repeated in the dance discourse of that time.

Despite all this, Duncan’s decision to perform only dances that referred to Antiquity was not an obvious one. Nude statues from Antiquity and decorations on ancient vases were also common in 19th-century pornography and racy variety theatre performances, where nudity was performed with the aid of paint and body stockings. Tunics and togas alluding to Antiquity wrapped these sensual performances in the robes of art.[15] Duncan’s early supporters also interpreted her performances and the fluttering fabrics of her costumes in erotic terms. Later, the dancer’s private life – particularly her sexual relationships and illegitimate children with Edward Gordon Craig and Paris Singer – alienated her more conservative supporters, especially in Duncan’s native United States. Unlike many of her contemporaries, however, Duncan managed to represent herself as ‘high culture,’ dancing her ‘Antiquity’ in a seemingly improvisational way to the symphonies of Beethoven or piano pieces by Chopin.[16]

Duncan did not share the enthusiasm that some of her contemporaries had for reproducing ancient dances and music. Her use of concert music in works that were supposed to be simple and spontaneous in their movements divided contemporary opinions. Duncan sought to express emotion and stressed the spirituality of her dancing, but especially after the First World War, her critics pointed out how her adult body no longer corresponded to the aesthetic ideals of ancient statues. The emphasis given to fleeting impressions in her dancing also meant that even Duncan’s defenders did not write much about the compositional aspects of her dances, let alone the methods of her art (her dance as technique or a system to be taught).

Duncan captured attention in part because she first performed in the salons of high society just as the amateur interest in Antiquity and body culture emerged and ballroom dancing culture was undergoing a rapid change. As Theresa Buckland has shown, 19th-century women of high society were accustomed to using the ballroom as an instrument of power: the society ball determined who belonged to society and who would marry whom. However, with the emergence of the bachelor culture in the 1880s, young men fled the ballroom in droves. The daughters of the women who organised balls were left with the salon, a public space within the private home, where a dance performance now became an integral part of the earlier practices of musical and recitative performances, as well as tableaux vivants (staged pictures), skits and plays.[17] At the salons Duncan met wealthy patrons whose generosity made her career possible, especially in London and later in Central Europe.

Duncan founded a small dance school in Berlin in 1904, and later another in Bellevue, France. Duncan’s performances were joined by six students who, as a group, became known as the Isadorables.[18] They are largely to thank for the fame and legacy of Duncan’s dance style, particularly in the United States. The tragic death of Duncan’s own children in 1913 brought her much sympathy, and in 1917 Duncan allowed her pupils to begin using her surname, although she never legally adopted them. Attracted to socialism, Duncan eventually married the Soviet poet Sergei Esenin in 1922, but the marriage lasted only a year. However, because of the marriage, Duncan was a Soviet citizen when she died accidentally in 1927.

Antiquity and Systemic Racism

The social upheavals caused by the First World War also changed attitudes towards Antiquity. Neoclassicism – another kind of return to Antiquity – emerged in ballet, partly as a reaction to the uncertainty and political polarisation created by the war. For conservatives, men crippled by the war and women increasingly present in the workplace shook up normative gender roles, forcing changes in notions of masculinity and femininity. At the same time, the heroes of women’s political and economic empowerment were dancing the latest ballroom dances of their time – the very ragtime dances that the previous generation had condemned as degenerate. The flapper culture was born, in which gender roles and norms reflected a very different understanding of dancing bodies and modern life in general.

In the literature of the time, art dance and the aesthetic and moral values associated with it were increasingly contrasted with the entertainment of urban youth culture. For those with conservative values, metropolitan cabarets were proof positive of the impending decline of the West. As Julie Malnig has shown, women’s magazines of the 1920s illustrated sanitised and ‘chaste’ versions of the popular ballroom dances of the era as a kind of commodity through which women could achieve the conservative, middle-class ideal of a nuclear family and the values associated with it. The focus on white, married role models was particularly important for this culture.[19] ‘Wild’ versions, such as those performed by perhaps the biggest star of the 1920s, African American and French citizen Josephine Baker, belonged on sensationalist stages and in nightclubs.

Josephine Baker’s popularity as the image of modernity also helped to overhaul notions regarding racialised bodies, nudity, movement and how dance signified. For example, as Beth Genné has shown, Baker directly influenced the movement language used by George Balanchine in his neoclassical ballets.[20] The distinction between free form dance and dancing on variety stages or in ballrooms was therefore nowhere near as sharp as often presented, as few dance professionals had enough personal means to refuse paid gigs. In the 1910s and 1920s, many young people also turned to art dance in the hope of another kind of stardom: variety theatres were a gateway to the cinema.

Late 19th and early 20th century discourse about dances of Antiquity was not only about nostalgic escape from the present. Rather, it was politicised rhetoric about rescuing all of Europe. The health benefits of dance were linked to the wider body culture, particularly the Olympic movement, but also to eugenicist ideas of a better, future humanity. Because the body emulating ancient ideals was aesthetically pleasing according to these ideals, it was primarily a normatively healthy and good-looking body; and after the war, hope for the future rested on the health of such young bodies. Set in a nostalgic landscape with references to classical Antiquity, the white, dancing bodies were comforting to turn into salvation narrative for an entire crippled generation.

In Germany in particular, the ideological overtones of early 20th-century art dance led to its alliance with the extreme right. In a way, the 1926 German documentary film Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty) anticipated this aesthetic convergence between the ancient tradition, free dance and Nazism, although Rudolf von Laban’s choreography Vom Tauwind und der Neuen Freude (Of Spring Wind and New Joy), commissioned for the opening of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, was too modernist for the National Socialists. However, both Laban and another leading figure in German modern dance, Mary Wigman, were sympathetic towards the National Socialists, which tarnished their reputations for a long time.[21] The corresponding racist legacy in the rhetoric of ‘pioneers of American modern dance’ (or American exceptionalism overall) has been less often discussed.[22]

In examining the history of dance, it is important to remember the eugenicist, racist aspects idealising the normatively ‘healthy’ body of Antiquity. These ideals produced a structural whiteness as a starting point for the study and theorisation of dance, where the ‘natural’ body is enclosed in an unintentionally racist and ableist whiteness of the discourse. Art dance has, in other words, done its share in supporting the racialising, heteronormative and patriarchal mindset still promoted by the extreme right, because the aesthetic ideals of dance are always also political.

Notes

1 Today, it is understood that the legionary system and roads of ancient Rome significantly increased the movement of people from one side of the empire to the other, with Romans from Africa (known at the time as ‘Mauritania’ or ‘Ethiopia’), for example, settling permanently in Britain. A better understanding of the polychromatic nature of Greek and Roman art has also called into question the aesthetic ideal of whiteness or fair skin previously associated with Antiquity. See e.g. Leach et al. 2010; Benjamin 2006. On the importance of whiteness in race theory in ancient Greece and the intertwining of race theory with art, see Leoussi 2016; Painter 2010, esp. 59–71.

2 Duncan 1928/1996, esp. 58–60. It is noteworthy that Duncan, in her own words, was not directly inspired by ancient art, but by the ways in which Antiquity was represented in 19th-century art. Her brother Raymond Duncan, in contrast, was very interested in ancient culture.

3 E.g. Walsh 2020; Gutsche-Miller 2020; Dorf 2019.

4 Steele 2001; Francis 2002, 1–38.

5 Steele 2001; Francis 2002, 1–38; Preston 2011, esp. 182–190.

6 Satama 2021.

7 Blasis 1830, 68–69.

8 Desrat 1895.

9 Emmanuel 1896, esp. 151–186.

10 Barrow 2010; Dorf 2019; Gutsche-Miller 2020; also Järvinen 2012.

11 Ruyter 1999; Preston 2011.

12 Daly 2002, 112.

13 E.g. McMahon 2016. As Painter 2010, 220–227 points out, late 19th-century theorists of race were primarily interested in creating a hierarchy of different white races.

14 E.g. Walsh 2020; Corbin & Courtine & Vigarello 2005 and 2006; Eichberg 1990..

15 Barrow 2010, 219–226.

16 Dorf 2012. Duncan also had relationships with women, most notably the poet Mercedes de Acosta, but she was not as open about them as she was about her relationships with men. Loïe Fuller, who helped Duncan to launch her career, was much more openly lesbian; and Helen Moller, praised by the poet e.e. cummings, likely had to close her dance school in the late 1910s because her dancing was associated with lesbian love.

17 Buckland 2011.

18 Anna Denzler, Maria-Theresa Kruger, Irma Erich-Grimme, Elizabeth Milker, Margot Jehl, and Erica Lohmann. Duncan later moved her school to France.

19 Malnig 1999.

20 Genné 2018, 68, 78–84; Dee Das 2020.

21 Kant 2016; Keilson 2019.

22 See e.g. Daly 1995; Scolieri 2019; Stanger 2021.’Pioneer’ refers directly to the white settlers’ colonial conquest on which Duncan 1928/1966, 242–245 founded both her personal history and her vision of the future of dance. Similarly, ‘American’ really only means the United States, here, not the two continents.

Literature

Barrow, Rosemary. 2010. “Toga Plays and Tableaux Vivants: Theatre and Painting on London’s Late Victorian and Edwardian Popular Stage.” Theatre Journal 62 (2): 209–226.

Benjamin, Isaac. 2006. “Proto-Racism in Graeco-Roman Antiquity.” World Archaeology 38 (1): 32–47. doi.org/10.1080/00438240500509819.

Blasis, Carlo. 1830. The Code of Terpsichore: The Art of Dancing. R. Barton. London: Edward Bull.

Buckland, Theresa Jill. 2011. Society Dancing: Fashionable Bodies in England, 1870–1920. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Burt, Ramsay & Huxley, Michael. 2020. Dance, Modernism, and Modernity. London: Routledge.

Caffin, Caroline & Caffin, Charles H. 1912. Dancing And Dancers Of Today: The Modern Revival Of Dancing As An Art. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company.

Carter, Alexandra & Rachel Fensham, eds. 2011. Dancing Naturally: Nature, Neo-Classicism and Modernity in Early Twentieth-Century Dance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Corbin, Alain & Courtine, Jean-Jacques & Vigarello, Georges eds. 2006. Histoire du Corps, vol. 3: Les mutations de regard. Le XXe siècle. Paris: Editions Seuil.

Corbin, Alain & Courtine, Jean-Jacques & Vigarello, Georges, eds. 2005. Histoire du Corps, vol. 2: De la Révolution à la Grande Guerre. Paris: Editions Seuil.

Daly, Ann. 2002. Done into Dance: Isadora Duncan in America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Dee Das, Joanna. 2020. “Dance That ‘Suggested Nothing but Itself’: Josephine Baker and Abstraction.” Arts 9 (1): 23 doi.org/10.3390/arts9010023.

Desrat, G[ustave]. 1895. Dictionnaire de la Danse. Paris: Librairies-Imprimeries Réunies.

Dorf, Samuel N. 2019. Performing Antiquity: Ancient Greek Music and Dance from Paris to Delphi, 1890–1930. New York: Oxford University Press.

Dorf, Samuel N. 2012. “Dancing Greek Antiquity in Private and Public: Isadora Duncan’s Early Patronage in Paris.” Dance Research Journal 44(1): 3–27.

Duncan, Isadora. 1928/1996. My Life. London: Victor Gollancz.

Duncan, Raymond. 1914. La Danse et la Gymnastique. Conference paper, 4 May 1914. Paris: Akademia Raymond Duncan. Accessed 31 January 2013. archive.org/details/danceman062.

Eichberg, Henning. 1990. “Forward race and the laughter of pygmies: on Olympic sport.” In Fin de siècle and its legacy, edited by Mikuláš Teich & Roy Porter, 115–131. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Emmanuel, Maurice. 1896. La Danse Grecque antique d’après les monuments figurés. Paris: Librairie Hachette.

Francis, Elizabeth. 2002. The Secret Treachery of Words: Feminism and Modernism in America. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Fritzsche, Peter. 2001. “Specters of History: On Nostalgia, Exile, and Modernity.” The American Historical Review 106 (5). DOI:10.1086/ahr/106.5.1587.

Garelick, Rhonda. 2007. Electric Salome: Loie Fuller’s Performance of Modernism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Genné, Beth. 2018. Dance Me a Song: Astaire, Balanchine, Kelly, and the American Film Musical. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gutsche-Miller, Sarah. 2020. “The Limitations of the Archive: Lost Ballet Histories and the Case of Madame Mariquita.” Dance Research 38(2): 296–310.

Järvinen, Hanna. 2012. “Dancing Back to Arcady: On Representations of Early Twentieth-Century Modern Dance.” In Dance Spaces, edited by Susanne Ravn & Leena Rouhiainen, 57–77. Odense: University of Southern Denmark Press.

Kant, Marion. 2016. “German Gymnastics, Modern German Dance, and Nazi Aesthetics.” Dance Research Journal 48(2): 4–25.

Keilson, Ana Isabel. 2019. “The Embodied Conservatism of Rudolf Laban, 1919–1926.” Dance Research Journal 51(2): 18–34.

Leach, S., Eckardt, H., Chenery, C., Müldner, G., Lewis, M. (2010). “A Lady of York: migration, ethnicity and identity in Roman Britain.” Antiquity 84 (323): 131–145. doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00099816.

Leoussi, Athena S. 2016. “Making Nations in the Image of Greece: Classical Greek Conceptions of the Body in the Construction of National Identity in Nineteenth-Century England, France and Germany.” In Graeco-Roman Antiquity and the Idea of Nationalism in the 19th Century, edited by Thorsten Fögen and Richard Warren, 45–70. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Malnig, Julie. 1999. “Athena Meets Venus: Visions of Women in Social Dance in the Teens and Early 1920s.” Dance Research Journal 31:2, 34–62.

McMahon, Richard. 2016. The Races of Europe: Construction of National Identities in the Social Sciences, 1839–1939. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Painter, Nell Irvin. 2010. The History of White People. New York: W.W. Norton.

Preston, Carrie J. 2011. Modernism’s Mythic Pose: Gender, Genre, Solo Performance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ruyter, Nancy Chalfa. 1999. The Cultivation of Body and Mind in Nineteenth-Century American Delsartism, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Satama, Manna. 2021. Tanssia antiikin näyttämöllä: Lukianos ja tanssin puolustus. Kinesis 12. Helsinki: Taideyliopiston Teatterikorkeakoulu. kinesis.teak.fi/lukianos.

Scolieri, Paul. 2019. Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stanger, Arabella. 2021 Dancing on Violent Ground: Utopia as Dispossession in Euro- American Theater Dance. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Steele, Valerie. 2001. The Corset: A Cultural History, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Walsh, Shannon L. 2020. Eugenics and Physical Culture Performance in the Progressive Era: Watch Whiteness Workout. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Contributor

Hanna Järvinen

Hanna Järvinen a university lecturer and department head at the Performing Arts Research Centre of the Theatre Academy, docent in dance history at the University of Turku, and Honorary Visiting Research Fellow at De Montfort University in Leicester. She has researched authorship and genius as well as the performing arts canon and the use of power in the light of feminist and postcolonial research traditions. She is also interested in issues of modernity and materiality at the intersection of performance and performing arts and dance orcid.org/0000-0001-9081-9906.