The 1960s were a period of intense movement, both politically and culturally, with the emergence of new phenomena and the struggle of opposing forces. The wave of decolonisation after the Second World War swept across Africa, and the international community finally responded to South Africa’s policy of apartheid. The Cold War that began in the 1950s had divided the world into Soviet and US interests. In the United States, a broad civil rights movement fought for human rights and equality against racial oppression. Utopias of an alternative, freer and more equal society were fuelled by left-wing ideas, ecological thinking and the countercultural hippie movement, which opposed the conservatism and social conformity of the 1950s. The movement was characterised by sympathy for minorities, folk music, protest songs, an interest in Asian philosophies and religions, and pacifism. Left-wing ideas and anti-war movements also radicalised students on a large scale in Europe. Feminism emerged as a major social force with the slogan “the personal is political,” and the advent of the contraceptive pill gave women more control over their own bodies.

By the end of the decade, however, the collectivist and communal spirit of the era had begun to change, although the San Francisco “summer of love” of 1967 and the great Woodstock music festival of 1969 still kept the flame of counterculture alive. After the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the utopia of the Marxist state began to fade. Many traumatic events, such as the political assassinations of prominent leaders (John F. Kennedy in 1963, Che Guevara in 1967, Martin Luther King in 1968) and the ongoing war in Vietnam, began to direct the gaze into the private and individual realm. The radical openings of the 1960s, both in art and in social norms, began to become mainstream, and new phenomena were able to be examined and valued in a way that continues to influence the art and society of our time.

The new aesthetic thinking, attitude and style of the 1960s later acquired several names: we speak of late modern or postmodern art and art philosophy. The grand narratives, such as the Enlightenment idea of human liberation, had lost their credibility, and this was reflected in a reassessment of the rules, norms and function of art. The boundaries between popular and high culture were blurred, mass media and commercial aesthetics became part of the art field. The framing of objects and practices, mixed media, quotations, irony and humour, improvisation, everyday themes and the highlighting of artistic processes all pointed to the idea that art is a living and changing part of the field of exploration and production of cultural meanings. Pop art, op-art, minimalism, conceptual art, Fluxus art movement and happenings, the Black art movement, avant-garde jazz, beat poetry, multidisciplinary and performance art are part of the impressive legacy of 1960s art.

In terms of dance aesthetics and objectives, the concept of postmodernism is difficult to define, but it is a handy rough temporal marker. In this text, the postmodern is above all a philosophical starting point for the idea that we cannot define any single fixed basis or ultimate transcendent signifier of existence. Truths are considered as discursive linguistic structures and processes that seek to be revealed and deconstructed. Art is also seen as part of a cultural process of meaning creation and deconstruction.[1]

Alongside this linguistic approach, the premise of perception and experience is also seen as part of postmodern thinking in dance art. Embodied being-in-the-world is always first and foremost local and historical, and dependent on each cultural context and community. As a cultural phenomenon that is both embodied, experiential and discursive, dance, according to the postmodern approach, cannot be assigned a single origin or foundation, but rather its trajectories intersect as shifts, leaps and boundless influences of embodied and cultural knowledge.

American postmodern dance reflected both the efforts of the European avant-garde of the early 20th century to systematically explore the foundations of artistic languages of expression, and the features of postmodernism associated with the blending and crossing of cultural, normative and aesthetic boundaries.[2] In the 1960s, the range of dance expressions continued to expand and diversify. The relationship with society and the world became on the one hand more everyday and directly interactive, and on the other hand more individualised through artistic experimentation and the development of artistic awareness and theory.

In the United States, a racial divide remained between white experimental dance and Afrodiasporic dance, which drew on Black community and history. African American dance emphasised the relationship of dance to community, but also dance as a subject of academic study. Civil rights activism allowed people to talk about their history and roots in a new kind of public relationship.[3] White postmodern dance, however, emphasised individual artistic and institutional questioning, the exploration of artistic methods, changes in choreography, performer, performance space and audience relationship, and mixing different arts in performance situations.

This article examines dance through some of the new phenomena of the 1960s and the features, works and artists that continue to influence dance art today. These include an emphasis on bodily perception and movement experience, a move away from the representation of dramatic and literary content through movement, and the influence of Asian philosophies on dance theory and practice. This latter theme will be explored through the work of choreographer and pedagogue Erick Hawkins. Choreographer and educator Anna Halprin developed dance teaching and choreography based on movement research and improvisation, as well as an interactive relationship with the environment and community. Choreographer Simone Forti created Dance Constructions through a choreographic concept and a score, unconnected to the choreographer’s personal movement expression, reflecting the phenomena of conceptual art, minimalist sculpture and installations in dance.

Judson Dance Theater introduced a new way of working as an artistic collective, bringing together individual acts, styles and ambitions under the common concept of Dance Concerts. Judson systematically explored and radicalised the foundations of dance and crossed the boundaries between the arts and popular culture through multidisciplinary artistic performances and contemporary art theoretical discourse. These features will be illuminated through descriptions of some of Judson’s Dance Concerts and the work of artists such as Yvonne Rainer, Elaine Summers, Fred Herko, Steve Paxton, Carolee Schneemann and Robert Morris. The relationship of African American dance to postmodern dance is illustrated through social status, differences in interests and possibilities, and artistic goals. Examples of postmodern African American artists include choreographers, dancers and dance teachers Gus Solomons jr. and Blondell Cummings. Finally, the discussion of art theory of the period and concepts whose definitions are not only contested but continue to influence our understanding and theorising of contemporary dance.

The Turn to the Bodily Perception in Dance – Erick Hawkins

After the Second World War, Zen Buddhism and Taoist philosophy and related embodied practices had a strong influence on the art scene in the United States. Choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage’s interest in Zen Buddhism, which emphasises being egoless, perception and experience, influenced their artistic aims. Cunningham sought to detach movement from its mimetic relationship with reality and developed chance-based methods for creating choreographic structures.

The artistic development of choreographer and educator Erick Hawkins (1909–1994) was also influenced by his interest in the philosophical principles of Zen Buddhism and Taoism and the art theory, dance aesthetics and choreographic thinking derived from them.[4] In his art, Hawkins combined the understanding of the significance of ritual and myth in Western culture offered by the study of ancient Greece with the perennialist view of the body–mind connection and perceptual experientialism proposed by East Asian philosophies.

According to Cynthia Novack, Hawkins, like other American postwar choreographers, turned to a way of conceiving the body that is neither ideal nor symbolic, but rather phenomenological. For Hawkins, the body is both a natural instrument, a subject of the laws of movement and gravity, and an expression of lived experience. The dancer must “think-feel” and be in a state of “intellectual knowing with sensuous experiencing.”[5]

The perception and awareness of embodied experience led Hawkins to develop both an artistic aesthetic manifesto and a new method of dance practice, the Hawkins Dance Technique. In his artistic manifesto ‘revolution is the theatre of perception’Hawkins places direct experience as the main principle of dance. According to Hawkins, in the theatre of perception, movement is a spontaneous event of perception understood in experience. The theatre of perception is a kind of invitation to a ceremony of awareness, it is a theatre of sensuous intelligence. The theatre of perception is poetic, concrete, direct and immediate. There is no alienation, for the awareness of the perceiving dancer is a participation in the totality of being. “Sensuousness is living in the now, in immediacy; therefore there is no alienation”.[6]

Hawkins’ artistic manifesto is linked to a wider phenomenon in postmodern Western art, called the “turn to the perception,” and the attempt to look at the relationships between materials, forms and temporal processes rather than relations of representation. By consciously articulating bodily existence, it was possible to free oneself from the symbolism of dance and approach a self-reflective movement. Susan Leigh Foster describes this turn in perception as a shift from the dramatic expression and dance symbolism of American modern dance towards reflection as the primary frame of reference for performance.[7]

The turn to the perception also meant a change in the way dance was studied and approached pedagogically. Hawkins’ ideas about the sentient, sensing body, the unity of opposing forces such as the balance of action and non-action, and the necessity of kinaesthetic functionalism were largely developed under the influence of both Eastern philosophies and kinesiology.

Hawkins developed an innovative approach to dance technique based on the principles of movement from kinesiology and anatomical research, thus creating a bridge to the somatic practices of contemporary dance. Unlike Martha Graham’s dance technique based on dynamic contrasts and tensions, Hawkins’ technique seeks free-flowing movement patterns and transitions. The phrase “the body is a clear place,” which describes the experiential and anatomical functionalism of Hawkins’ technique, is also the title of his essay on art theory.[8]

Hawkins’ approach has many similarities with that of choreographer Deborah Hay, who started at Judson Dance Theater in the 1960s and has played a major role in contemporary dance, especially in the 21st century. Like Hawkins, Hay places bodily perception as the starting point for the art of dance and performance. Hay’s practice, however, appears more radical than Hawkins’ in that Hay does not prescribe or presuppose any particular form of movement, dance technique or movement aesthetic beyond the method of perception and the interpretation of the choreographic script.

Hawkins’ philosophical thinking on art

In his reflections on art theory, Hawkins defines modern dance as a journey into the possibilities offered by both the Eastern aesthetic-experiential principle and the theoretical principle of Western aesthetics. The art of the theoretical principle is needed to make the conceptual and the theoretical, mythical and allegorical, that which constructs our world, experienced in the work of art, understood in experience and situated in the totality of life. Movement as a spontaneous event of perception and understood in experience, in turn, leads Hawkins to define dance as a metaphor of existence rather than life. The latter refers to perceptions of life, personal or general, and the representation of these perceptions, self-expression. The former refers to existence as such, to the occurrence of impersonal being and the participation of the person in it. When Hawkins stands on stage in his solo Pine Tree, he is, in his own words, not trying to express himself, it is not a matter of self-expression, but of just existing. In this way we arrive at an appreciation of existence, which is always a kind of miracle as an experience.[9]

For Hawkins, the highlights of his works have been where the choreography has been able to show only the existence of being as such. Hawkins writes that it is a great challenge to be still enough inside while dancing so that a simple awareness of existence, of being there, can emerge. There are no power play or psychological levels involved. The psychological dimension cannot understand the existential poetry of movement, it is caught up in the egocentricity of life. The existential dimension, instead, is communion with nature and other beings, in the dimension of poetic dwelling and consciousness.[10]

Improvisation and Kinaesthetic Awareness – Anna Halprin

If you can think of dance as the rhythmic phenomena of the human being, reacting to the environment. If the audience accepted that definition, then I’d say, yes, it’s dance.

[11]

Choreographer, dancer and teacher Anna Halprin (1920–2021) called herself a breaker of the rules of modern dance.[12] By this, Halprin referred to a modern dance approach based on a movement vocabulary and a choreographic movement language derived from a particular dance technique. Halprin rejected such an approach to dance when she continued to pursue the career of her teacher, the philosopher and dance pedagogue Margaret H’Doubler (1889–1982), in her exploratory work on anatomy and kinesiology. Functional movement based on anatomy and the student’s creative relationship with movement led Halprin to develop a way of working based on kinaesthetic awareness and improvisation. Through improvisation, Halprin was also able to explore the relationship of movement to nature, community, language and music.

Margaret H’Doubler

Margaret H’Doubler was a philosopher and a pioneer of university-level dance education. H’Doubler graduated from Columbia University, where she studied philosophy and aesthetics. She developed a pedagogy that supported students’ creative way of moving. She was interested in anatomy and creativity – how the body responds to working with gravity, for example, when lying or standing on the floor, and how students describe and articulate their movements in scientific terms. H’Doubler developed her dance theory from these experiences and wrote several books on dance and pedagogy. Her approach to dance education was to enable everyone to live as fully as possible and she believed that the educational process must be based on scientific facts about the nature of human life. In her thinking and teaching, she focused on kinaesthetic awareness in three stages:

- feedback, which provides information from muscles, joints and tendons;

- association, which occurs exclusively in the brain;

- action, which sends messages back to the muscles. (Wilson et al 2006, 22, 216–18, 291–94.)

H’Doubler made a significant contribution to the emergence of higher education in dance as early as the 1920s. In 1926, with her colleague Dean Sellery, she developed the first university-level curriculum with dance as a major at the University of Wisconsin. H’Doubler taught at Wisconsin until 1954 and was a visiting teacher until her death in 1982. Mabel Elsworth Todd’s ideas about the centrality of somatics and anatomy in dance pedagogy also influenced the development of Halprin’s views. Burt 2006, 56.

In addition to H’Doubler, important influences for Halprin included the ideas of avant-garde theatre-maker Antonin Artaud on material life forces,[13] exploring composer John Cage’s ideas on compositional strategies that allow for spontaneity, the ideas of minimalist sculpture on analogies with the mass and gravity of art objects and the human body, and Zen Buddhism.[14]

Halprin’s later career, which focused on therapeutic and communal dance, was influenced by ecological threads that emerged in the political counterculture, aspects of indigenous cultures and religions and their relationship to the land, and the early experiences of her husband, the architect Lawrence Halprin, with the Kibbutz community. Walter Gropius, founder of the German Bauhaus, was Lawrence Halprin’s teacher, and the practice of artistic workshops created at the Bauhaus was also carried over to Anna Halprin’s work and dance teaching in the 1950s.[15]

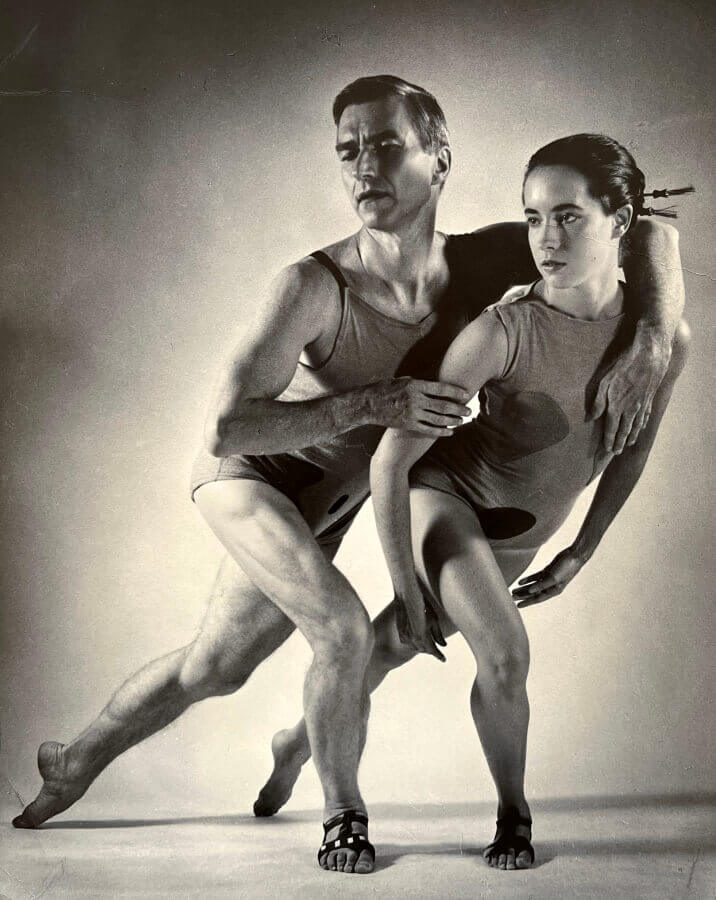

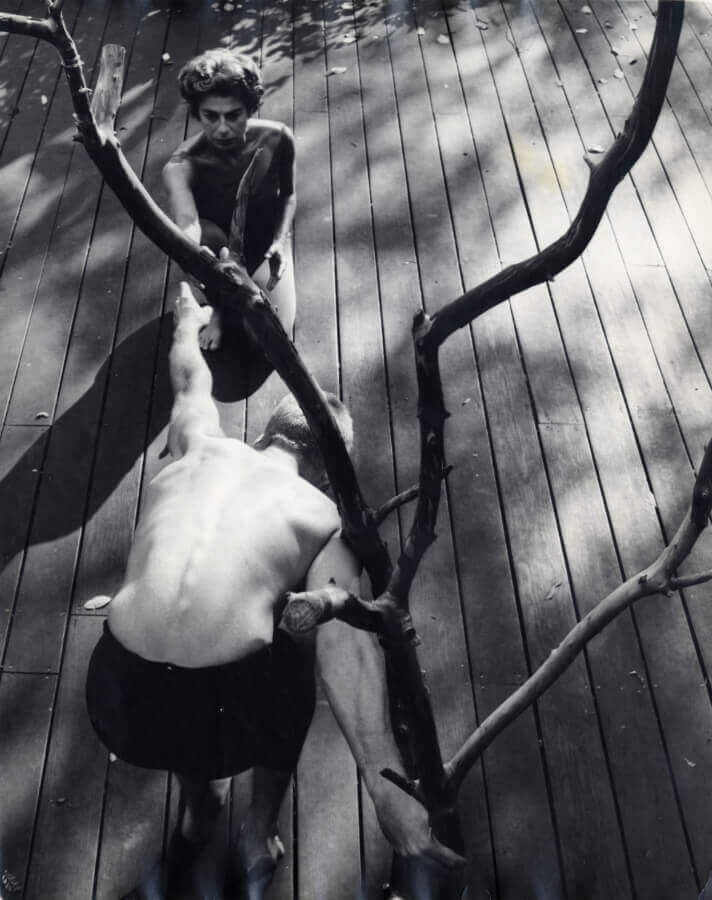

Halprin’s famous Dance Deck has undoubtedly played a particularly important role in dance history. It was a terrace built by Lawrence Halprin to serve as a large dance floor in front of the couple’s California house, in the middle of nature. Dating back to 1954, the structure became a place where annual workshops allowed artists from different disciplines to freely explore artistic possibilities and where Halprin developed improvisational, kinaesthetically aware dance with many young dance artists such as Simone Forti, Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Ruth Emerson and Judith Dunn.[16]

Not only dancers attended Halprin’s workshops, but also a diverse group of artists inspired by John Cage’s artistic ideas, including visual artist Robert Morris and composers La Monte Young, Terry Riley and Robert Ellis Dunn. The compositional structures and perceptual discourses of the work, as well as the task-based strategies that allow the dancer’s spontaneous interpretation to determine the structure and content of the work, were among the areas of interest. Tasks could include speech, poetry, sonic elements, natural objects, as well as a variety of choreographic structures and movement tasks.[17]

Halprin’s view was that the body is capable of all kinds of movement. To explore this potential, she gave dancers movement problems, called explorations. An example task could be running while moving the spine through any possible positions. The body responds to the task and puts the dancer into a movement that goes beyond plan or habit. This kind of work increased the dancer’s kinaesthetic awareness and ability to discover and articulate movement in which each moment had its own particular quality. Kinaesthetic awareness was related to the ability to sense movement in one’s own body, to sense the body’s changing dynamic states, and to sense and observe movement in the surroundings, environment and nature.[18]

Halprin’s interest in anatomical and kinaesthetic starting points, improvisation and interaction with the environment and nature led to dance in which the audience and performers closely shared the same space and soundscape, and in which the presence of the dancers emphasised everyone’s bodily experience. Halprin was “concerned with the real world of things and beings in contact and not with the stage world of stage believability” and felt no need to prepare or add anything to the stage that did not already exist in the everyday world. What mattered was a body that was focused and receptive to the impulses that made the movement flow.[19]

This kind of reduced and simple presence was closely linked to the development of choreographic task aesthetics. The performer was not guided by self-conscious introspection or the expressive qualities of movement, but by a functional, non-representational and simple action, in which environmental interaction and embodied material relations, such as the manipulation of natural objects or auditory elements, were essential. Halprin’s interest in the ethical and experimental foundations of dance is also evident in the way in which the development of dance was guided by the recognition of and attunement to the autopoietic, self-determined dimension of nature.[20]

Since there is ever changing form and texture and light around you, a certain drive develops toward constant experimentation and change in dance itself. In a sense one becomes less introverted, less dependent on sheer invention, and more outgoing and receptive to environmental change. There develops a certain sense of exchange between oneself and one’s environment and movement develops which must be organic or it seems false… space explodes and becomes mobile. Movement within a moving space, I have found, is different than movement within a static cube.

[21]

Studying and working at Dance Deck in the late 1950s, and especially in the 1960 summer workshop, has gone down in dance history as an important influence on the development of many of the key figures in the Judson Dance Theatre collective. Anna Halprin’s own artistic career, both as a choreographer and teacher, was significant and continued uninterrupted for over six decades. Her discoveries in the 1950s led to experimental stage choreography in the 1960s and later, from the 1970s onwards, to an increasingly therapeutic, social and communal approach to dance.

Halprin did not aim for an unchanging repertoire. Instead, the works were based on tasks that allowed both variations in compositional structure and spontaneity and variation in the dancer’s interpretation. In Birds of America (1960), a work to the music of La Monte Young (Trio for Strings), dancers, two of whom were Halprin’s children, interacted on stage with various objects, including large bamboo sticks, while dancing improvisational tasks of choreography.[22]

In Parades and Changes (1965), Halprin used choreographic notation or task score. Using drawings and general instructions, the score described the process of the performance, its physical action, time and place, and a variable sequence of scenes. In the key scene, the performers slowly peeled off their clothes and spread large brown sheets of paper on the floor. They then moved with and among the papers, tearing, folding, lifting and touching the paper to create a living, cloudy and changing landscape. This kind of work, evoking a naked and collective sensuality, an attunement to and entanglement with materiality, was not easily received by the public in 1965. The New York performance in particular provoked a storm of protests from the audience, insults were shouted, objects were thrown on stage, and Halprin was almost arrested by the police for her work.[23]

Halprin: Parades and Changes

Parades and Changes was divided into six scenes, including audience participation and slow disrobing and dressing, as well as the scene with large sheets of paper, pictured. The choreography was by Anna Halprin; the original performance was by Halprin and San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop members Larri Goldsmith, Paul Goldsmith, John Graham, Kim Hahn, Daria Halprin, Rana Halprin, A.A. Leath and Jani Novak, with music by Folke Rabe and Morton Subtnik. The work premiered on 5 September 1965 in Stockholm. US venues included the University of California at Berkeley, the University of California at Los Angeles, San Francisco State University and Fresno, California. Performances continue today.

The reception of the work prompted Halprin to think more deeply about the interaction between audience and performers. Halprin became increasingly interested in the empowering and social aspects of dance and began to incorporate therapeutic concepts and techniques into her work from the 1970s.[24] Soon Halprin’s works moved out of the theatre and into the streets and nature, and she developed the idea of using dance rituals to connect communities and help people cope with social and emotional tensions.

Over the following decades, Halprin developed various methods,[25] projects and works aimed at cultural, communal and individual empowerment. Halprin’s themes included ethnic inequality and discrimination, minorities, multiculturalism and healing rituals, AIDS/HIV stigma and facing community crises. Many of the works are large-scale performances of up to 100 people, which are performed again and again, decade after decade. Circle Earth (1986) and Planetary Dance (1987),for example, are collective, community dances, performed year after year by new people and generations. Anna Halprin’s workshops at the Dance Deck, in the natural surroundings of the Mount Tamalpais, also became familiar to many artists working in the field of contemporary dance, and her pioneering work on the ethical, ecological and communal aspects of dance has inspired artists for over half a century.[26]

Choreographic Concept – Simone Forti

You start with an idea, like that you’re going to build a ramp and put ropes on it and then you’re going to climb up and down. So you don’t start by climbing up and down, and then developing movement. You don’t start by experiencing the movement and evolving the movement, but you start from an idea, that already has the movement pretty prescribed.

[27]

Simone was the first person I’d heard of who would say, I’ve brought a dance and I will read it to you. And it was an action not performed, it was an action that was natural action outside the human being, it was a situation and that was her dance.

[28]

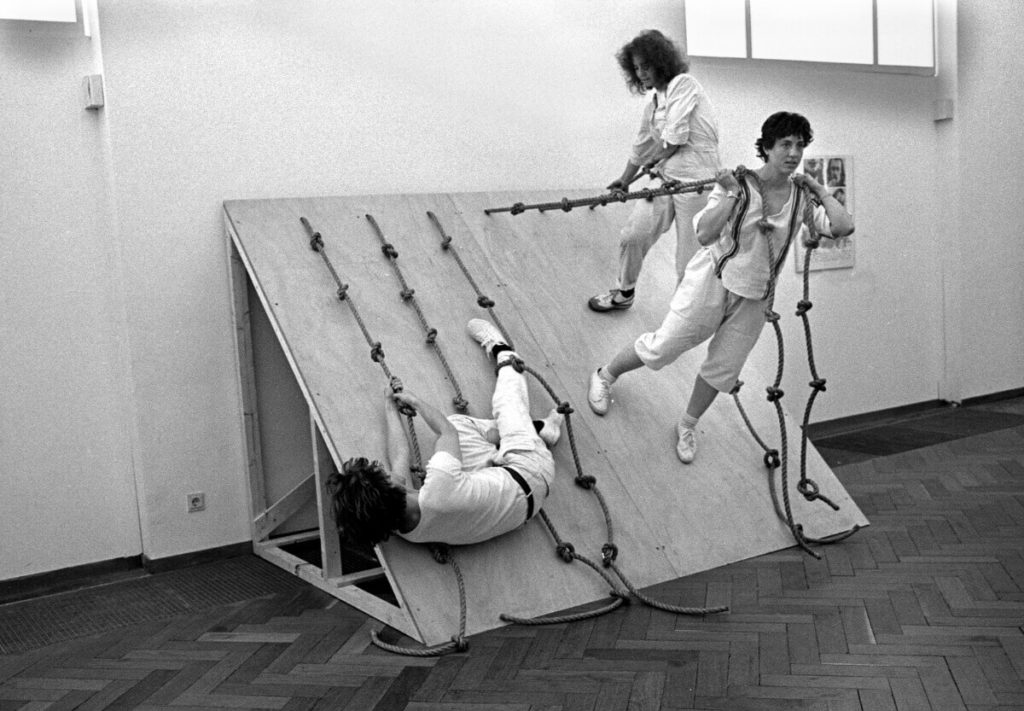

The artistic work of choreographer and dancer Simone Forti (1935–) appears as two distinct periods, both in terms of their origins and their significance. Forti is both a concept-oriented choreographer from the early 1960s and a dancer-choreographer and pedagogue who has focused on task-oriented somatic-improvisational choreography since the 1970s. Forti’s importance in the development of contemporary dance crystallises in her idea of “choreographic concept”in the 9-part series of short works Dance Constructions, which are both presented, analysed and explored in several dance studies and writings of the 21st century.

From a dance history perspective, it is interesting to see what kind of multidisciplinary artistic and experimental influences led to the creation of miniature works in 1960–1961. One important early influence on Forti was her years as a student of choreographer Anna Halprin in California (1956–1959). Forti also experimented with dancing in the classes of Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, but did not experience a fruitful connection with their approaches. According to Forti, Cunningham was a master of adult, differentiated and articulated movement. Forti herself felt her own movement was a holistic and undifferentiated reflex, typical of babies.[29]

The first work that interested Forti after moving to New York was Robert Whitman’s unconventional happening, E.G.,shown in a crowded small gallery in 1960. Halfway through the piece, Whitman took a flying leap directly over the audience’s heads, grabbed some bars and swung a way out of sight while the soundtrack repeated incessantly yes, yes, yes…munch munch munch munch. The same year, Forti herself appeared in Whitman’s American Moon. In it, Forti was tasked with handling various objects, including climbing ladders, stomping around on scaffolding, covering another performer with rags and crawling under an inflating balloon. When performing, Forti realised that the tasks were not meant to focus on the quality of the movement, but on the act itself and the fact that the action had its own concrete presence.[30]

In the autumn of 1960, Forti participated in a composition workshop with musician Robert Ellis Dunn and dancer Judith Dunn at Merce Cunningham’s studio, together with several dancers who later formed the Judson Dance Theater collective. Dunn, who was the accompanist for Cunningham’s dance company, began the workshop by presenting scores bycomposer John Cage. One notation in particular, Imperfections Overlay, proved significant to Forti. It involved pages of clear plastic on which there were dots that corresponded to imperfections Cage had found in some sheets of paper. The pages of clear plastic were to be dropped onto a graph and where the dots fell determined the place and time of the events. But the nature of the events to be performed was left entirely up to the performer. It could be ringing a bell or jumping off a rock – anything.[31] Forti felt that Cage had not relinquished control completely, but had shifted the artist’s stamp to a new dimension or point of leverage. Cage’s influence was still strongly felt in the original structure of the procedure and in the quality of the spatiality of the autonomous events. For Forti, Imperfections Overlay opened up for the first time a clear point of reference from which she felt she could form a precise relationship to indeterminate choreographic systems.[32]

Cage’s notation gave the workshop a good start. Dunn instructed the participants to work quickly at first and to produce a lot of material to learn from and discuss. He insisted on being aware of the process of each piece – the methods each person used, whatever they were. This meant having a clear understanding of how to create a work.

The initial choreographic idea already included an assumption about the method, which led to the final result. Forti explains that for her, the crucial thing was to understand that she could choose and define the distance between the point of control and the movement performed. For Forti, control came to signify a kind of dramaturgical operation: “I came to see control as being a matter of placement of an effective act within the interplay of many forces, and the selection of effective vantage points. This made me start trying to take precise readings of what points of control I was using and wanted to use, and to what effect.[33] From then on, Forti sought precision and accuracy in the choreographic control points she used and for what purpose.

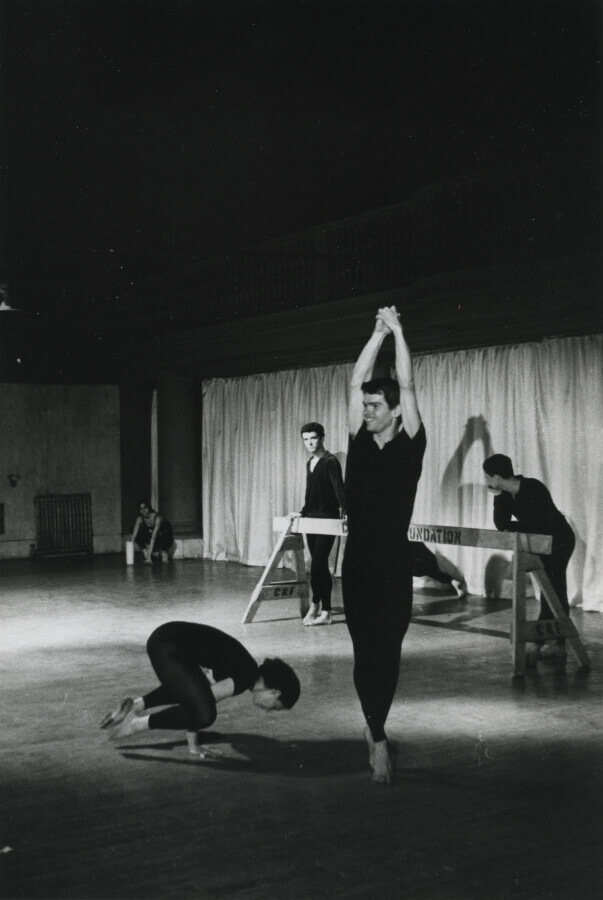

Dance Constructions

At Christmas 1960, Robert Whitman invited Simone Forti to a happening evening at the Reuben Gallery with artists Jim Dine and Claes Oldenburg. The evening featured Forti’s first two miniatures, See Saw (performed by Yvonne Rainer and Robert Morris) and Rollers (performed by Forti and Patty Mucha). The following spring, in 1961, composer La Monte Young asked Forti to create a complete series, which was performed at Yoko Ono’s loft apartment on Chamber Street. Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things featured seven new miniatures, with performers including Morris, Rainer and Steve Paxton.

Dance Constructions were 10–20-minute works performed in a shared space with the audience. The choreography consisted of a simple functional idea and the instructions according to which the works were executed and performed. The choreography does not evolve thematically, through movement and variation, but events follow one another as defined by the choreographic concept or at random.[34] Interaction with sculptural elements – the seesaw, ropes, platforms and boxes – is central to most of the works, and all are based on interaction between performers or between performers and spectators.

In Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, different works were performed in different parts of the space, sometimes overlapping in time, and the audience had the opportunity to view the works from different angles and distances than is usual. The works were functionally concrete and interacted with material elements, presenting themselves to the viewer as an intersection of live sculpture and performance. Movement had no mimetic or narrative intent in relation to the objects and elements, but through movements recognisable from the everyday world, such as climbing, hanging, swaying, pulling, or speech, singing and vocalisation, the performers became part of the world shared with the audience. This interactivity was reflected in the fact that the default duration of the works varied from situation to situation, determined by the time needed to perform and watch the activity.

In her Handbook in Motion (1974) Forti describes all her miniatures as they were first performed at a community evening in 1961.[35] Since then, Forti has allowed some of the works to be adapted and transformed for performances in the 21st century. In 2015, the New York Museum of Modern Art acquired the works for its collection, and several art museums in Europe have presented them as exhibition events.[36]

Abbreviations for descriptions of the Dance Constructions

In See Saw, a plank placed on top of a sawhorse forms a seesaw, with both ends attached to the wall with rubber bands. A toy under the plank makes “moo” sound under the weight of the swing. A man (Morris) and a woman (Rainer) sit and move on the board, and the slightest change in balance causes the seesaw to move. After a while, the woman sways, screams and swings up and down on the board. Then the man reads aloud from Art News, and finally Simone Forti sings a country song she heard on a record. The piece lasts about 20 minutes.

Rollers has two large wooden boxes with wheels underneath. A performer sits in each box. Three ropes are attached to each box, which the spectators pull in different directions at different speeds and in different ways. During the box ride, the performers improvise a vocal duet.

In Slant Board, three to four performers climb and move calmly on a wooden platform raised at a 45-degree angle on six ropes attached to the platform. The dancers rely on the knots in the ropes and are in constant motion for the 10 minutes of the piece or, when tired, rest in place supported by the ropes. The sound of the ropes falling on the wood panel creates its own rhythmic dynamism to the movement.

In Huddle, six to nine people grab each other by the shoulders to form a tight cluster and dense mass of people standing up. In turn, one of them breaks away from the mass, carefully climbs over the group and returns to the mass.

In the Hangers, five sturdy rope loops placed close together hang from the ceiling and extend almost to the floor. One performer balances, standing, on each of the ropes. In addition, four walkers criss-cross the small space between the performers, causing the performers hanging from the ropes to sway, twist and move.

Platform features two large wooden, arched boxes under which the performers, a man and a woman, disappear in turn. They whistle to each other for 15 minutes and then emerge.

From Instructions consists of two mutually exclusive instructions. One of the men has been told to lie on the floor for the entire piece. The other is instructed to tie the lying man to the wall. The result is a physical conflict.

In Censor, one person is vigorously swinging a pot full of nails and another is singing loudly. The task is to balance the volume of the sounds.

In Herding, six people walk up to the audience and politely ask them to move in the direction indicated. This is repeated several times.

The evening also featured Accompaniment for La Monte’s 2 sounds and La Monte’s 2 sounds.

The work is intended to accompany a 12-minute recorded composition by La Monte Young, which features two continuous, powerful voices. One person stands in a loop of rope suspended from the ceiling. The rope is suspended in the space so that it is clearly in the side part, accompanying the piece La Monte. The assistant plays the tape, turns the rope around several times and lets the rope open and rotate freely until the movement stops.

Forti’s way of using space and creating choreography with objects and materials opened up a whole new horizon between visual arts, performance and dance. According to Martha Joseph, Forti’s work framed the relationship between the sculptural object and the moving body in a way that anticipated many of the ideas in 1960s minimalist sculpture. They suggested that objects and bodies have similar properties: both are matter with mass, volume and weight, and both create spatial relationships with the objects and bodies around them. Forti’s works allowed us to observe the intersection of sculpture and performance and to think about what we know about things through our bodies.[37] A similar work exploring the intersection of sculpture and non-mimetic performance can be seen in the minimalist sculpture Box with the Sound of Its Own Making by Robert Morris from 1961. The work consists of a wooden cube on top of an exhibition column and a three-and-a-half hour recording of the sounds of the construction of the cube.[38]

Forti’s works can also be seen as exploring the nature of social relationships, as dancers had to carry out the instructions in collaboration with each other, sometimes also with the audience. The works are embodied attempts at communal and material negotiation, collective work, the perception of belonging and sensual multiplicity. Because the choreography required the collaboration of performers and spectators, the works renewed the conventional relationship between audience and performers.

Just as John Cage’s Imperfections Overlay changed the notion of composition and the role of notation, Forti’s miniatures expanded the notion of the nature of choreography. What is central in these works is not the thematic or variational development of movement, but the simple actions defined by choreography in the interaction of dancers with each other or with the audience. This principle means that the works are not built on the personalities of the performers, but are repeatable and recognisable as identical works without specific named performers.

Simone Forti herself did not perform in the Judson Dance Theater collective even though she worked with many “Judsonians” from Halprin’s summer courses and Dunn’s workshops onwards. From the 1970s onwards, Forti is known for her works based on deep somatic awareness and task-based dance improvisation, as well as for her decades-long teaching career.

Multidisciplinary Dance Collective – Judson Dance Theater 1962–1964

My body remains the enduring reality.

[39]

The Judson Dance Theater originated as a composition workshop held by musician Robert Dunn and dancer Judith Dunn in 1962 at Merce Cunningham’s studio, at the end of which Robert Dunn organised a performance of the works created during the workshop at the Judson Memorial Church in New York. The workshop was attended by a number of dancers and musicians, including Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, David Gordon, Deborah Hay, Meredith Monk, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer and Gus Solomons jr. In addition to them, more than 300 artists – dancers, visual artists, musicians, composers, filmmakers and photographers – participated in Judson’s 16 concerts and other performances in the 1960s.[40]

Judson Dance Theater, despite its name, was not a centrally run dance theater group, but a loose collective that operated for only a few years, producing all-night dance concerts featuring a diverse range of artists and their works. The Judsonians often collaborated artistically in each other’s performances, but by the end of the 1960s many of them were pursuing their own careers in different ways and directions.[41] Judson’s innovative and experimental spirit was part of New York’s multidisciplinary artistic framework and art discourse. The happening events of Allan Kaprow,[42] Jim Dine, Robert Whitman and Claes Oldenburg in galleries and lofts between 1959 and 1962 questioned art as a static object and placed the art exhibition within the realm of the “theatrical” event. Judith Malina and Julien Beck’s The Living Theatre (1947–) developed a non-fictional theatre based on the actor’s political and physical commitment to using theatre as a vehicle for social change. Multidisciplinary art movement Fluxus, a kind of “fluid anti-art,” emerged in the late 1950s and one can trace its roots to the experimental composition courses at the New School for Social Research led by John Cage.[43]

Instead of an overt political agenda, part of Judsonian radicalism targeted the internal conventions and institutional foundations of dance art with awareness of art theory.[44] In this way, it indirectly engaged in a social debate about representation and the values attached to art forms and practices. While the work of artists such as Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Anna Halprin and Simone Forti had already produced many artistic innovations, it was the artists working in Judson’s circle who first broke the dam of diversity with their creative productivity to create a phenomenon that shaped dance history and has perhaps been more commented on, studied and canonised than any other event in 20th century dance history. It was, however, a characteristically white European American neo-avant-garde, in which African American art and postcolonial influences were marginalised or completely invisible. The exclusion was not intentional, but as Thomas DeFrantz writes, Judson’s artistic aims did not address the avant-garde of African American art and artists whose starting points, values, and interests were shaped by social activism and racial oppression on the one hand, and exploring and developing Afrodiasporic cultural histories on the other.[45]

The artistic aims, methods and aesthetics of the works presented at Judson were not consistent, even between different works by the same artists. Due to the later careers of a few dance artists, such as Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs and Yvonne Rainer, Judson is often associated in the dance canon with abstract postmodern dance, minimalist expression and the use of everyday movement. In reality, Judson’s circle experimented and created from a wide range of aesthetic starting points, which this text seeks to illustrate through descriptions of works.

In dance history, Judson has become significant because it is seen as a kind of culmination point of modern dance’s departure from the dramatic or symbolic tradition. The Judsonians sought new ways of working with choreographic premises and methods that could be seen to have parallels with the aims of post-dramatic theatre. Post-dramatic theatre no longer considered the dramatic text as central to the creation of the performance event and moved from embodying a literary myth or role to an individual embodied presence. In their own way, these features were present in Judson’s performances.[46]

The Judsonians systematically explored new syntactic and conceptual possibilities of dance, expanding its frames of reference to popular culture, everyday life, visual arts, film, sculpture, experimental music and performance. New ways of making included real-time commentary on choreography during the performance, kinaesthetic irony, unexpected anatomical and syntactic possibilities, choreography as a task score, and the use of everyday movement, object manipulation and speech as part of the choreography, and sometimes people who had no dance training were performers. A reflective awareness of the means of performance, the shared situation with the audience, the improvisational spontaneity of the task aesthetic and the experimentation with the compositional relationships of the different elements also gave the audience an active and dialogical role as the recipient of the work. According to Susan Leigh Foster, it is precisely these features that characterise the audience relationship and the aims of postmodern, non-mimetic dance. In contrast to the dramatic tradition of American modern dance, where all elements of performance – movement, music, staging and costume – are fused together to convey a single message to the audience, objectivist (non-mimetic) dance actively separates the different media, thus challenging the role of the spectator as a passive recipient.[47]

Judson’s choreographers were trained dancers, but they also gave space on stage to artists who had no dance training.[48] The works could use movement that was both pre-choreographed and based on improvising from tasks, movement referencing a particular dance technique or style, or movement that was everyday and source-based, such as in sports photographs. The model of the mute dancer or the symbolic figure was broken and a person living their life emerged. Dance and speech can be intertwined as parallel, separate, fragments, commentary on choreography, choreographic notations as vocalisations or song. The works dealt with both everyday and constructed objects and materials that were integral to the performance, rather than stage elements that visually supported the choreography. Accompanied by pop, classical or experimental new music, they were performed with live or different types of sound or in silence. The costumes could be simple, or they could be extravagant, camp, and of the most unusual designs. The pieces were relatively short, between five and 30 minutes long, and reading the script descriptions one gets the impression that they were often intensely dense in terms of events.[49]

As in Simone Forti’s works or happenings, Judson expanded the traditional relationship with the audience. The experimental nature of the works, which were often open-ended and task-based, new dramaturgical solutions and multimedia, the shared space with the audience and the self-reflective commentary on the works placed the audience in an active role. Immersion in the fictional framework created by the performance became impossible.[50]

By showing everyday movement in a partly improvised composition, the Judsonians offered the audience a new way of seeing the human body and the dancer. According to Foster, improvisation made the viewer aware of what we might call bodily intelligence. Improvisation shows how intelligence is not just a realm of the mind but a continuum of body and mind. For the spectator to follow improvisational dance as a personal kinetic thinking the mimetic and thematic representational elements of the dance had to be reduced and replaced by functional concreteness of movement and the choreography had to have a conceptual starting point that could be followed. Self-reflective or “objectivist” dance can be seen as an attempt to break away from idealised experience and to show the performing human being in a more humble position among other beings and things. If dance simply represents individuals in movement, it is not assumed that dance represents an idealised or (universal) experience that might be common to all human beings.[51]

Features of Judson’s Dance Concerts

Judson’s first dance concert featured performances of works created in Robert Dunn’s workshop. Dunn chose to call the evening a dance “concert” to refer to the historical tradition of intimate performing in dance and chamber music. It marked a departure from the literary, narrative and theatrical tradition of modern dance and created a link with, for example, Isadora Duncan’s performance evenings and music concerts: the audience would encounter different qualities and moods, in a shared space with the performers.[52]

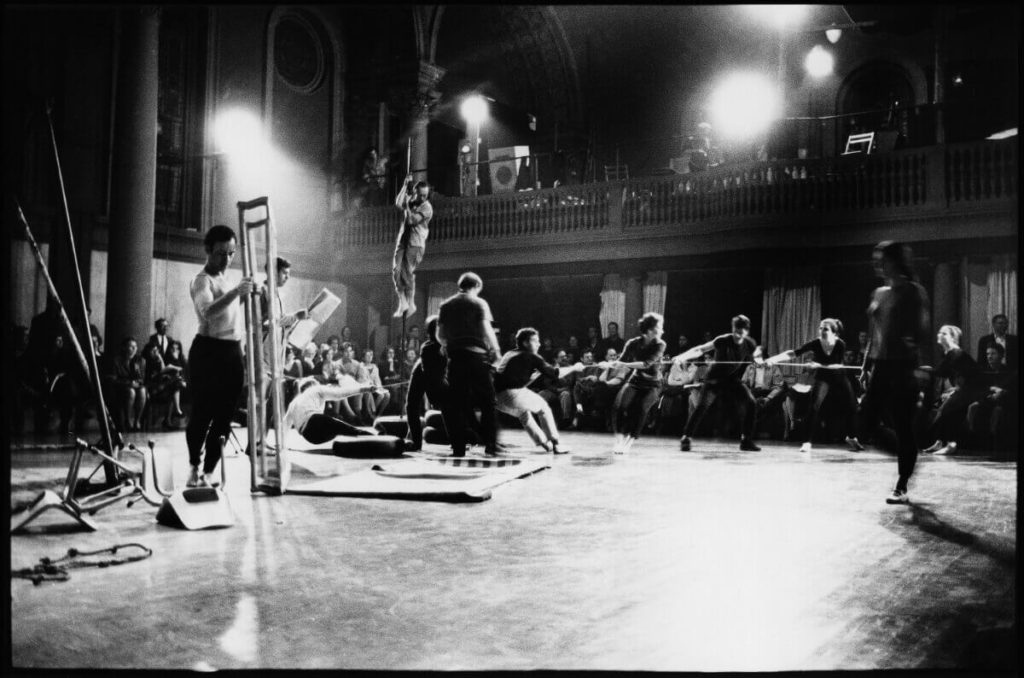

The very first dance concert, #1, was an example of Judsonian versatility. The evening featured 23 performances, the first of which was Elaine Summers’ experimental film Overture. The evening included asymmetrical solos and group dances, dances with and without music, live and recorded music, speech and song, slow and fast-paced performances, simple and complex choreographic structures, and simple and elegant costumes. The evening took place in the heat of July and, contrary to the organisers’ expectations, the Judson hall was packed to capacity and the evening lasted from 8 p.m. to midnight. The key to the evening’s success, according to New York Times critic Allen Hughes, was Summers’ film, whose parallels between random events – such as children at play, parked trucks, an excerpt from W. C. Fields’ silent film – led the viewer away from the conventional cause-and-effect relationships of everyday logic.[53]

According to Sally Banes, concerts #3 and #4 stood out. In them, the Judson Dance Theater collective was well established, the music and composers played a major role, and the dancers who had previously worked with Cunningham had diverged from many aspects of Cunningham dance technique, although they still shared an exploratory and expansive approach to the bond between dance and music. In Concert #3, the relationship of the works to the music varied particularly widely. Yvonne Rainer used music from the Romantic period in her works We Shall Run (Hector Berlioz) and Three Seascapes (Sergei Rachmaninov), as well as La Monte Young’s avant-garde work Poem for Tables, Chairs, Benches. Steve Paxton made the music for Word Words, which was a collaboration with Rainer. The music was a separate physical activity, performed on a different night. The music took the form of a performance in which Paxton stood inside a transparent, mechanically inflating plastic bubble and Rainer played sound fragments she had recorded from the space.[54] The dance Certain Distilling Process by composer Philip Corner was a musical experiment in which the dancers’ movements served as cues for the musicians to play. Some of the dances were performed without music, while others used music either composed for the choreography or previously recorded in a more traditional way.[55]

Rainer’s choreography Three Seascapes

Rainer’s choreography is an example of exploring the choreographic possibilities between movement and music. The work consisted of three choreographic gestures and movement with three different types of music and dance-music relationships.

Choreographic script for Three Seascapes:

- Running around the periphery of the space in a black overcoat during the last moment of Rachmaninoff’ Second Piano Concerto.

- Travelling with slow motion undulations on an upstage-to-downstage diagonals during La Monte Young’s Poem for Tables, Chairs, Benches.

- Screaming fit downstage right in a pile of white gauze and black overcoat.[56]

Three Seascapes can be seen as a didactic experiment. By presenting three different types of music – powerful romantic piano, a non-harmonious musical idea and a violent human sound produced by the dancer’s body – it presented three possible relationships to movement – the correspondence, opposition or independence of movement and music.

Concert #3’s varied repertoire in 1963 explored the movement’s origins and the dramaturgical possibilities of choreography, as well as the evolution of the artists’ themes between concerts. In We Shall Run, Yvonne Rainer drew a parallel between Hector Berlioz’s requiem piece Tuba Mirum and everyday movement: a group of 12 dancers dressed in everyday clothes run at a steady pace in various parallel, simultaneous and unison formations throughout the seven-minute duration of the work. Steve Paxton and Rainer’s Word Words was structured around choreographed solos and included (near) nakedness that aspired to unisex sameness. Word Words began with a seven-minute solo by Rainer, followed by exactly the same solo by Paxton, and finally the same choreography with complex movement was performed a third time in unison. The other works in the concert varied widely in movement starting points and aesthetics. In Carolee Schneemann’s Newspaper Event, the movement was born from the intertwining of tasks and newsprint, while in Robert Huot and Robert Morris’ Wa, the movement was born from whipping the instruments in violent determination. Steve Paxton presented a pantomime dance in English, and Arlene Rothlein’s It Seemed to Me There Was Dust in the Garden and Grass in My Room relied on lyrical expression. In Ruth Emerson’s solo Giraffe, themovement had a spontaneous, violent energy and an indulgent quality.[57]

Elaine Summers’ Instant Dance, performed in Concert #1, is an example of the complex structure of task-based group choreography. Summers had experienced that often so-called “chance dances” used hidden action. The movement was predetermined in rehearsals and the choreographic tasks were pre-set, so that the viewer had no way of knowing what methods were being used, and thus no way of consciously following the dancers’ choices. In Instant Dance, Summers wanted to create a game-like spontaneity in the choreographic structure, where there is no hidden action but the choices are visible to the audience. Summers also hoped that the focus on a complex task would lead the dancer to break away from a certain way of performing, a facial expression and a staring gaze that Summers and the Judsonians experienced as a fake result of their dance training. In Instant Dance, seven dancers manipulate large blocks of styrofoam, with different coloured walls defining the movement tasks differently for each dancer. In addition, the colours and shapes of the pieces were linked to a number of other variables that determined in great detail factors such as the duration, tempo, number of movements and use of space. The complexity was further increased in the second phase of the choreography, in which the movement tasks were transferred from one dancer to another.

Elaine Summers: Instant Dance

The piece featured seven dancers (Ruth Emerson, Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Gretchen MacLane, Steve Paxton, John McDowell, Summers) manipulating large pieces of styrofoam of various shapes. The shape, colour and numbered walls of the blocks served as movement assignments for the dancers. The positions and orientations of the pieces were varied by throwing them around, resulting in a different movement task for each dancer. The pieces determined the location and the type, speed, number and rhythm of the movements. For example, Ruth Emerson’s choreographic score specified that a cone meant movement should be in the air, a cube meant standing on tiptoe, a column meant standing and a ball meant sitting. Yellow meant very fast movement; blue, fast; purple, medium fast; red, slow and pink, very slow. The numbers controlled the rhythm and amount of movement. The instructions were to repeat the movement five times and in a specific rhythm: 1=1 (an insistent pulse), 2=2/4, 3=3/4, 5=5/4. Each performer also had a specific colour for their costume. As the performance progressed, the movement tasks became more and more complex, shifting from one performer to another. To the viewer, the piece appeared to be a children’s game that was interesting to watch, at least for most of the time, as New York Times critic Allen Hughes wrote.[58]

In addition to the relationship between dance and music, the Judsonians also explored the relationship between speech, text and movement. Rather than the kinetic representation or theatrical performance of the text, they explored the non-symbolic layering of meanings formed by text and movement. An example of this is Yvonne Rainer’s autobiographical solo Ordinary Dance, a combination of speech and movement, which had originated in Robert Dunn’s choreography workshop and was performed in Concert #1. In this work, the dancer’s fragmentary speech and movement occur simultaneously, but without narrative connection, at an intense tempo and with dramatic momentum. According to contemporary critics, the work received a roaringly positive reception from audiences and is considered one of Judson’s classics alongside David Gordon’s Mannequin Dance.[59]

Yvonne Rainer: Ordinary Dance

The work presented a choreography in which the dancer’s speech and movement are simultaneous, but without a narrative link. The choreography consisted of unconnected movement phrases and repetitions while Rainer talked about the addresses that she had lived in different cities, her primary school teachers and the sounds associated with different places. The choreography consisted of fragmentary observations, such as a ballerina demonstrating classical movement or a woman hallucinating in the New York subway, as well as concrete dance movements and simultaneous speech. According to Rainer, the work had a dramatic momentum, brought about by the intense combination of concentrated movement and speech. According to the comments collected by Banes, the audience was passionately impressed by the work’s performative quality and associative power.[60]

The diversity and varying aesthetics of the artist personalities who appeared in Judson are reflected in the works of Fred Herko or David Gordon. One of the performers in the concert #3 was Fred Herko, who did not conform to the image of purist minimalist “Judsonism” and instead openly expressed a queer perspective and carnivalesque aesthetic. Fellow artists and critics remember that Herko was a charismatic performer who often created a theatrical structure to his performances, adding humour, pathos and a camp aesthetic.[61] In his #1 evening solo, Once or Twice a Week I Put on Sneakers to Go Uptown,[62] Herko was dressed in a multicoloured bathrobe, wearing a metallic veil in front of his face, and circled the vast stage doing hand gestures to music by Erik Satie.[63]

Concert #3 Little Gym Dance before the Wall for Dorothy is remembered with fondness by critic Jill Johnston. She describes Herko meeting his audience with his characteristic ironic warmth and cynical attitude, dancing here and there in his characteristic way, mixing technical finesse with exuberant swagger, and finally exiting with his integrity as an insufferable rebel and capable dancer.[64]

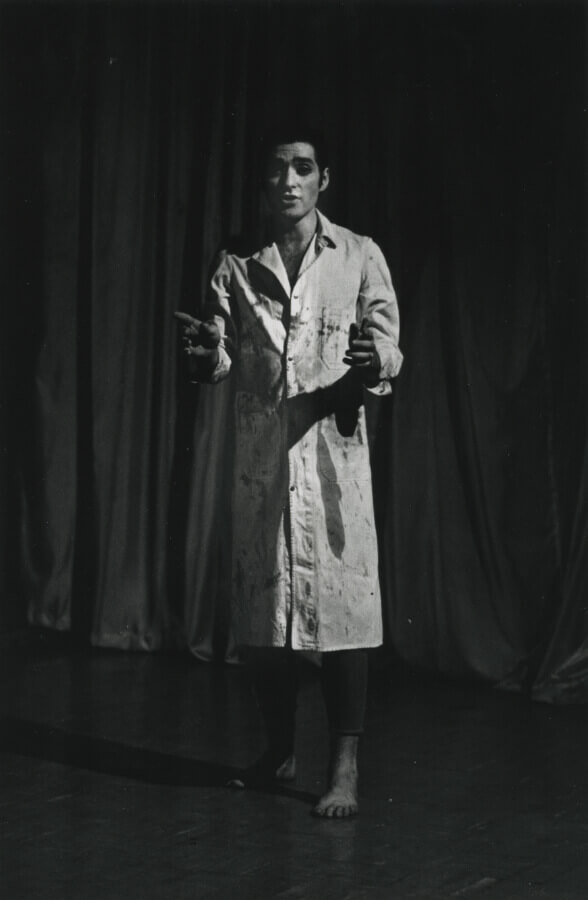

David Gordon’s Mannequin Dance is an example of aesthetics and dance that critics described as eccentric, macabre and expressive. The piece lasts nine minutes, during which Gordon sings two songs (Second Hand Rose and Get Married Shirley) and moves with virtuosic concentration from one body-twisting, awkward and strange position to another as he lands on the floor. To increase the macabre impression, Gordon was wearing a white blood-stained lab coat and, to augment the soundscape, James Waring gave balloons to the audience to inflate and then slowly deflate. Critics Diane di Prima, Jill Johnston, Deborah Jowitt and others described Gordon’s dancing as unprecedentedly moving. In contrast to the “distorted and dissonant” movements of 1930s modern dance, the contorted movements of Gordon and the previously seen Ordinary Dance by Rainer were not symbolically expressive – they did not explicitly express pain – but were movement components and concrete bodily possibilities alongside other movements.[65]

Performance at the Intersection of Choreography, Visual Arts and Performance – Materials and Objects

Judson Dance Theater was characterised by artist-led collective work and democratic programming. In keeping with this principle, many artists who had no dance training performed and created work at the Judson. Notable roles included Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Morris, Carolee Schneemann, Charles Ross, Philip Corner, La Monte Young, Gene Friedman, Al Carmines, Claes Oldenburg and Alex Hay. The artistic collaboration from different artistic perspectives further expanded the choreographic working methods and the Judsonists’ relationship to materials, objects, the performer’s body and composition. The following works illustrate the interdisciplinary approach and the new relationship with materials.

Carolee Schneemann, originally trained as a painter and later widely known for her work in performance art and multimedia, performed her works at several Judson concerts.[66] Newspaper Event for seven dancers and a large amount of newsprint, presented in Concert #3, is an example of visual art, performance and choreography meeting in a Judsonian framework. The frame established an initial choreographic and embodied relationship to the performance, but also gave space to address from new perspectives some of the parameters central to dance, such as time, space, movement patterns and the way of performing.

Schneemann was not enthusiastic about the use of the chance method, or about “methodical choreography” in general, which, in her view, did not give enough room for sensory sensitivity, intuition, perception and bodily experience. The tradition of live performance is often built on a dramaturgical premise of time and space. Rather than editing the material according to the dramaturgical expectations of theatrical aesthetics, for Schneemann the temporality and spatiality of performance were perceptible components in which the material articulation of the work could be extended. Instead of a methodical choreographic work, Schneemann described Newspaper Event as a cellular organism interchanging its parts.[67]

Schneemann also sought her own relationship to the definition of movement qualities. She did not create movement from a typical continuum of anatomical functionality and movement themes, but used the same terms as in her visual artwork, which she wanted to make concrete and gestural. Through gesticulation and gestation the “fundamental life” of each material becomes concrete. Dancers can do this through any part of the body or sound.

One aim was to create more kinetic objects than dance, and to blur the boundaries of the individual body as people and activities blend into the newsprint sea. Another aim was to create a situation where the interaction would be physical, intimate and spontaneous, rather than the dancers acting as autonomous units even in group dances, as was often the case in chance choreographies.[68]

Newspaper Event – Notation

The Newspaper Event, which lasted about 10 minutes, was built around a series of improvisational tasks requiring mutual interaction, such as horizontal or vertical activities or fragmentary, everyday phrases, and five choreographic principles:

- The primary experience is the body as your own environment

- The body within the actual, particular environment

- The materials of that environment – soft, responsive, tactile, active, malleable (paper…paper)

- The active environment of one another

- The visual structure of the bodies and the material defining space.

In the work, each of the seven dancers had a choreographed body part: the spine for Arlene Rothlein, legs and face for Ruth Emerson, shoulders and arms for Deborah Hay, neck and feet for Yvonne Rainer, hands for Carol Summers, head for Elaine Summers, fingers for John Worden. Schneeman herself was a “free agent” with crawling. The dancers used these body parts as a source of movement and focus in relation to choreographic tasks and newsprint. Some dancers’ tasks included phrases such as “I’ll huff and puff,” “that’s beautiful,” “I need breakfast,” “you little prick” and “you dumbass.”[69]

The different roles of the dancers and the paper sea intermingled in a way that made the dancers appear as one interconnected body, and this organic metaphor interested Schneemann in other Judson works, including her most famous, Meat Joy (1964).[70] Schneemann’s influences included Simone de Beauvoir’s feminism, Antonin Artaud’s theatre of cruelty and William Reich’s ideas on the relationship between sexuality and politics. According to Ramsay Burt, Schneemann eschewed the John Cage style, Zen-influenced, anti-expressive minimalism he called “fro-zen,” and instead saw embodiment (including nudity) as a source of pleasure, passion and emotional power.[71]

Robert Rauschenberg also bridged visual art and dance, designing sets and costumes for Merce Cunningham and Paul Taylor from 1954 onwards and playing a variety of roles at the Judson in the early 1960s. In his visual work, he combined elements of painting and sculpture, incorporating everyday objects and materials into his “combinations.” In the staging of dance works, Rauschenberg was interested in the performative dimension of artefacts and objects, and began to incorporate various objects and constructions into a moving body. Rauschenberg was also interested in the function of his own body as a material for art, and found it attractive in comparison to the fixed form of painting, which was made up of “external materials.”[72] Rauschenberg explored these dimensions in Judson in the roles of choreographer, performer, lighting and set designer.

Rauschenberg’s choreographic debut was Pelican (1963), performed at Concert #5.[73] In it, Rauschenberg and the artist Per Olov Ultved skated on stage wearing large circular “wings” made of parachute silks. In addition, a virtuoso dancer, Carol Brown, danced on stage in a tracksuit and pointe shoes. The trio was accompanied by a sound collage by Rauschenberg of alarm sounds, radio and Handel’s music.[74]

Choreographer Steve Paxton recalls that Rauschenberg’s creative approach to materials and artistic work was instrumental in the formation of the Judsonian ethos of “work with what is available.” In Pelican, for example, Rauschenberg characterised his artistic choices as “the limitations of the materials as a freedom that would eventually establish the form.”[75] The collision of bodies and objects, such as wheels, parachutes and pointe shoes, and the framework imposed by these objects was the starting point for the exploration and creation of movement in Pelican. According to Paxton, this attitude was influenced by a Judsonian mindset where “restrictions aren’t limitations, they’re just what you happen to be working with.”[76]

Robert Morris, known for his minimalist sculpture and writings on art theory, created several choreographic works with the Judson Collective between 1962 and 1964.[77] Morris was particularly interested in the temporal and embodied relationship to sculpture and in art-making as a form of work – themes that Morris had encountered both in Anna Halprin’s workshops and in his performances of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions. In Site (1964), dressed in a white mask, white work clothes and gloves, Morris dismantles a cube of large white plywood boards by lifting and moving the boards from one place to another. Morris’ choreographed movements are deliberately minimalist and focused on the careful execution of the action. The choreography’s use of time and space is determined by the functional and pictorial orientation of the boards towards the audience. One plywood board is moved to reveal a nude woman, Carolee Schneemann, reclining on a divan in a posed position. The woman’s pose and setting mimic Manet’s Olympia (1863). Together with Morris’s action, the still life creates a complex landscape in which the cultural history of prostitution in Olympia, the passive nude body of the female artist, the gaze and work of the (male) artist, and the layers of meaning between figurative and abstract painting and between painting, sculpture and choreography intersect.[78]

In this new discursive environment for the history of dance, the artefacts and objects used by many Judsonists as part of their choreographies were adventurous: cardboard boxes, chairs, ladders, boards, mattresses, car tyres, ropes, fences and constructions. On the one hand, the associative meanings and “performative dimensions” of the objects, on the other hand, the relationship between bodies and objects were explored from various perspectives. Objects played a very special role in the works of Morris and Yvonne Rainer, albeit with different artistic intentions. What they had in common was a conscious relationship with the scale of the human body: Morris’ moderate scale of the human body tended to replace the monumentality of sculpture, Rainer’s the virtuosity of dance. Rainer saw much parallelism in the aspirations of minimalist sculpture and dance, so that the sculptural aim of “literalism” and “simplicity” coexisted with the task-like functions of dance.[79] On closer examination, however, Morris’s and Rainer’s aims differed. In choreography and performance, Morris emphasised human action: objects bring about human action, sculptural props serve the goal of human action. If this is not the case, the works become too “figurative” for Morris. Rainer was concerned with a more equal status for objects and humans. For Rainer, the appearance of the body as material – the object dimension of the body – was a way of breaking away from the “narcissistic” tendency of dance.[80]

In Rainer’s choreographies, dancers treated objects as compositional and associative entities, like text or movement. Objects also moved from one work to the next. For example, in Room Service (1963), Parts of some Sextets (1965), The Mind is a Muscle (Trio A and a Mat) (1968), the dancers treated the same mattresses in different ways. In Parts of some Sextets, the choreography included 30 or so different activities with 12 mattresses that the dancers were assigned and organised: they threw themselves onto the mattresses, crawled between them, jumped on them, carried and dragged the mattresses individually or in pairs, sat on the piles, etc. The mattresses organised the movement and became, in a sense, active participants on stage. Similarly, the dancers took on an object-like quality as they too were dragged around the stage.[81]

While “object-choreographies” expanded the field of choreography, the piece Rafladan, which closed Concert #3, questioned the definition of a dance work. It featured visual artist Alex Hay, dancer Deborah Hay and photographer Charles Rotmil. The work was performed mostly in darkness, the only source of light being a torch, which Alex Hay moved while standing behind the frame of a painting. Charles Rotmil played the sakuhachi flute, and Deborah Hay’s dance was only visible when the torchlight happened to hit her. New York Times dance critic Allen Hughes said the work raised a significant question about what defines or constitutes dance, and that such questioning was likely to have an impact well into the future.[82]

Judson’s collective approach, use of objects and materials, and multidisciplinary artistic collaboration was on full display at Concert #13, where sculptor Charles Ross built a material installation that filled the entire Judson hall. All of the evening’s performances took place there, and each of the 30 performers had a unique relationship with it. The installation included a large metal trapeze-type sculpture, a high platform made of boards, a seesaw, ropes, rings, ladders, boards, chairs and brooms.[83] The evening was billed as a “collaborative event” and, while celebrating Judson’s creative spirit, it also became a kind of turning point for Judson’s collective way of working.[84]

Gradually, the members of the collective branched off in their own directions to develop their own artistic aspirations. For example, Yvonne Rainer first formed her own dance group, which later became a major improvisational performance art group, The Grand Union (1970–1976), but then moved into filmmaking in the late 1970s. Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs founded their renowned dance companies, and Steve Paxton became known in the 1970s as a pioneer of contact improvisation. Deborah Hay retreated from New York for several decades to develop community dances and her distinctive relationship to the artistic origins of dance, and only returned to the field of professional dance in a big way in the 2000s, when she achieved considerable interest and success with 21st century contemporary dance.

Judson on Whiteness and Black Postmodern Dance

Judsonian postmodern dance of the 1960s has often been historicised as a white avant-garde and apolitical movement with little reference to cultural identity. In principle, the Judsonist attempt to break away from the tradition of dance’s sublimity and aristocracy, to deconstruct the fictional framework of dance and bring a more everyday aesthetic to dance, could have been fertile ground for African American culture and its political aspirations, especially if postmodern dance circles had been able or understood to analyse how many aspects of African and African American culture, so-called Africanisms, are assimilated into American art dance, as Brenda Dixon Gottschild has analysed in her book Black Dancing Body (2003). “White” postmodern dance is not only representative of the European tradition, just as “Black” dance is not only constructed from Afrodiaspora, but racist structures maintained a recurring division between “downtown” art discourse and “uptown” modern and Black dance, and few African American artists found in Judson a meaningful frame of reference for themselves at a time when the civil rights struggle sought to desegregate the United States.

Thomas DeFrantz analyses the causes of whiteness in postmodern dance, starting from the aesthetics and practices of modern dance.[85] In the mid-20th century, prominent choreographers of modern dance, such as Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham and Bella Lewitzky, selected dancers based on the dance skills required by the repertoire and the ideology of liberal “colour-blind role-casting.” Modernist abstraction allowed these white choreographers to avoid racial role casting but meant that stories about Black life and the meaning of those stories for Black audiences and artists were not told.[86] Judson in the early 1960s operated differently from the groups led by individual choreographers: collectively and with democratic artistic freedom. African American artists were not excluded, but the artistic freedom of Judson was used to pursue aspirations that few of them identified as their own. Susan Foster summarises the differences in their efforts in relation to tradition: the white dancers at Judson used radical, transgressive strategies to break with the dominant tradition of the white mainstream, unlike Black choreographers such as Eleo Pomare and Dianne McIntyre, who, in using new avant-garde jazz music in their work, did not break their ties with the African American dance and music tradition, but reassessed it and reconnected with its roots.[87]

According to DeFrantz, modernism meant a focus on form rather than realism and expression, while postmodernism meant a focus on structure by dismantling the foundations of construction and rejecting existing rules.[88] The task basis often used in Judson creates a structure for the choreography that the dancer executes. “Performing a task” meant performing that did not necessarily have to be understood as dance. The separation of tasks from dancing was a method that made Judson exclusive and limited its participants. DeFrantz points out that in the 1950s and 60s, few Black artists had the opportunity to treat task-making as art rather than mundane, low-paying, repetitive work. For the Black dancer, dancing was required special skills and virtuosity, and had to be treated as such, and Black dancers did not warm to Judson’s doctrine of dancing as an everyday person. For a Black dancer, performing “to do a task” might seem socially naïve. DeFrantz asks: what Black artist would want to perform tasks critical of the tradition of dance (which can be interpreted as failure and incompetence) in a public space in the midst of the Black civil rights movement in the early 1960s?[89]

Higher education was a distinguishing factor in the Judsonian frame of reference. In the 1960s, artists emerged who had a university education and an art theoretical ability to recognise and articulate the values associated with art practices. Avant-garde art’s response to the anti-intellectualism of the dominant art world was a reaction to the latter’s social conservatism. Many white artists were university students before they studied dance, but very few Black artists had access to university education and domestic or international study trips. A few exceptions had the opportunity to pursue both academic and artistic careers, such as choreographers Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus and Ishmael Houston-Jones, and postmodernists Blondell Cummings and Gus Solomons jr, who became key figures in the development of African American dance art for decades.[90]

According to DeFrantz, the bond and living connection to African dance tradition is also reflected in the relationship of African American dance to the audience and dance aesthetics. The movement of postmodern dance, with its emphasis on casualness and concreteness, allows for intimacy between the audience and the performance, but does not actually create interaction between them. The movement (e.g. Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs in the 1970s) is independent and cool, with no energy directed specifically towards the audience. Movement can be identified and watched but it cannot be “owned.” According to DeFrantz, in contrast to white postmodern dance, the audience relationship in Black modern dance is crucially different: the aim is to share ideas of energy and movement with the audience. It circulates energy through the audience to create flashpoints of communal engagement.[91]

Many of Judson’s artists later became aware of a certain political naivety in relation to African American culture and identity in the early 1960s. The limited social impact of avant-garde means also produced a political disillusionment that led many Judson artists to make new artistic, aesthetic and environmental choices in the 1970s. Although there was little convergence between the interests of white and Black art at Judson, in the 1970s they did converge in some frames of reference. The sparse political activism of white postmodern dance is represented, for example, by Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A performance at the People’s Flag Show in 1970. The ethical and social demands of the Black civil rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War served as the impetus for the show, which brought together many minorities around the theme of critical works in relation to the US flag. In Rainer’s Trio A performance, six dancers performed the choreography naked, with only the US flag hanging around their necks. The performance was provocative and artistically complex. It used metonymy to juxtapose an institutional-critical aesthetic structure with a political ideology. It thus proposed a common ground between the radical iconoclastic Trio A and radical liberal protest. By using the star-spangled banner in this way, the performers expressed their vision of the pluralistic and inclusive democracy they believe the US should be.[92]

According to Ramsay Burt, Trio A’s Flag Show performance was a kind of watershed, where 1960s idealism met its own political disillusionment or need for reassessment. In a discussion in 1986, Yvonne Rainer stated that she still felt committed to avant-garde ideas of marginality, intervention, subculture and resistance, but that the aesthetic means of attempting to address political problems needed to be constantly reassessed in terms of class, gender and race.[93]

Postmodernists Gus Solomons jr and Blondell Cummings