Multiple Modernism

Modernism can be understood broadly through criticality, experimentation and consciously challenging tradition. Rather than a single set of aesthetic and formal principles, modernism should be considered as a polyphonic and global phenomenon, or the plural form of the term, modernisms, should be used to highlight the diversity of phenomena.[1] Modernism has not been distinguished from avant-garde in the Finnish debate, although the conceptual difference between the terms is significant. The avant-garde is strongly concerned with changing society through art, while modernism refers more generally to the stylistic features of art and the expressions of modern life in art.[2]

Abstract painting, atonal music and stream of consciousness literature are often placed at the hegemonic centre of modernism. However, modernism also found expression in architecture, poetry, design, advertising, film, dance, fashion and various interdisciplinary forms. The long-standing canonical approach to modernism limited it geographically to the West, especially to the metropolises, temporally from the 1900s to the 1950s, and strongly to so-called high culture. The New Modernist Studiesthat have developed since the turn of the 21st century seek to push these boundaries and consider modernism as a transnational spread of influences beyond the Western focus.[3]

At the same time, there is a debate about whether the term “modernism” – whose canon has long been strongly masculine, heteronormative, English-centred and literary – is any longer appropriate. As modernism expands to encompass very different aesthetics and expressions, the terminology associated with it also refers to a great variety of phenomena that do not necessarily have clear common denominators. The terms modern, modernism and modernity therefore remain without a clear definition precisely because of their contextual nature, and may also cover contradictory or even opposing meanings.

The term “modern dance” refers to a form of dance modernism that sought alternatives to the technique, movement language and themes of classical ballet. The various trends in modern dance began to develop in the early 20th century, characterised by a movement language and technique based on each choreographer’s personal style.[4] To limit dance modernism to a formalist choreography that emphasises only the form of movement is to cover a very narrow area of this phenomenon. Indeed, dance as an art form expressing the experience of modern life has replaced the earlier idea of modernism as a kind of gradual development towards an increasingly abstract movement.[5] It is also important to see various forms of popular culture, from cabaret to musicals, and new social dances as expressions of modernism. Moreover, in dance, international interaction was particularly active, for example in comparison with language-based forms that required translation.[6]

The new modernist research raised the visibility of dance as part of modernism, while at the same time increasing the cross-artistic perspective. Instead of a linear narrative, modernism evolves as a complex international rhizome in which different artistic disciplines, such as literature, music, visual arts or dance, are in constant interaction with each other. For example, expressionist Wassily Kandinsky collaborated with dancer Alexander Sacharoff and Mary Wigman’s student Gret Palucca.[7] Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró contributed to the Ballets Russes’ performances with their costumes and sets. (see The Russian Ballet of Diaghilev (and a Few Others)) In this interdisciplinary activity, dance participated in a modernist exchange of ideas from a central bodily perspective. The ephemerality of dance appealed to the other arts. At the same time, it seemed to have a particular potential to embody the fluidity, polyphony and certain contradictions of experience of modern society.[8]

Early 20th Century Body and Dance

In one sense, the development of modernisms began in the 19th century, but from the 20th century onwards its various expressions grew exponentially and in very different directions. On both sides of the turn of the last century, dancers[9] began to look to create meaning in new ways that were not based on imitation of reality (mimesis). The academic traditions and techniques of dance art, perceived as rigid, were replaced by new means of expression and methodologies. Dance modernism encompasses a range of different expressions of dance, reflecting very different experiences of the social events of the period: wars, revolutions and politics, the development of science and technology, industrialisation or the emergence of a consumer society. Some expressions of dance modernism are thus even opposites of each other.

Technological developments offered artists new means of expression. In Paris, a major art centre of the fin de siècle, Loïe Fuller (1862–1928) rose to fame with her multi-artistic performances that combined dance and technology. In 1892, Fuller’s Serpentine Dance was the main attraction of the famous variety theatre Folies Bergère. In the dance, Fuller moved multimetric fabrics, on whose moving surface different colours and patterns could be projected thanks to the lighting design she developed. Fuller’s use of technology to create illusion succeeded in capturing the aspirations of art nouveau in dance.[10] Her popularity was so overwhelming that at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair she was given her own theatre and became the symbol of the entire exhibition.

The Evolution of Serpentine Dance

American actress Loïe Fuller started her career as an actress, touring vaudeville and burlesque stages as a teenager, not only in the United States but also in Europe. While working at London’s Gaiety Theatre in 1889, Fuller learned the skirt dancefrom its famous late 19th century performer, Letty Lind.[11] In the skirt dance, the dancer’s twirls and leg lifts were accentuated by the movement of the skirt. Fuller’s dance evolved from this skirt dance when she dressed up a long skirt in an empire-style dress, increasing the reflective surface of the light and the surface area of the moving fabric. At the same time, the movement of the fabric became the main means of expression in the performance.[12] This was in contrast to the dancing on burlesque stages, for example, where the large skirt was primarily a decorative frame for the presentation of the female body.[13] Gradually, Fuller used ever larger fabrics and held long sticks in her hands to extend the range of movement of the fabric. In the performances, the dancer’s body expanded into space as a movement of the fabric on the one hand, and disappeared invisibly into the folds of the fabric on the other.

The dance also has another, lesser-mentioned source of inspiration: the performances of Indian dancers that Fuller saw in Paris at the end of the millennium. Anthea Kraut has shown that Serpentine Dance contains kinaesthetic traces of the spirals and twists of Indian dancers. Inaddition to seeing Indian dancers, Fuller had performed in several oriental music hallor burlesque shows that used floating canvases to build a fantasy.[14]

Fuller was a tireless practitioner, researcher and experimenter in both movement and lighting design.[15] For her, dance was a combination of art and technology: a fusion of aesthetic, creative process and technical skill, where the movement of light and colour on the canvas could be calculated systematically. The Serpentine Dance evolved from its 1892 premiere into versions using increasingly larger fabrics and more complex light effects. Fuller darkened the space for her performance, which was new for dance performances. The technical complexity of the dances is illustrated by the fact that they required the work of 20 technicians to succeed.[16]

During the golden age of Parisian cabaret, dancers and actors were also superstars of the emerging popular culture, and “La Loïe” danced on famous advertising posters painted by Henri de Tolouse-Lautrec and Jules Chéret.

The Serpentine Dance quickly gained imitators on both sides of the Atlantic, and Fuller defended her copyright by suing the copiers of her dances. She also tried to patent the dance she had invented, but lost the lawsuit because it was not narrative or character-based. The court decision remained the precedent for choreography copyright cases in the United States until 1976.[17]

The experience of the modern world was also accompanied by a fear of the adverse effects of a rapidly industrialising and urbanising society.[18] It was believed to destroy the physical wellbeing of the body, and this was counterbalanced by an emphasis on the importance of body culture. As early as the 1830s, various body techniques were developed and disseminated in Europe and the United States.[19] They laid the foundations for the development of early modern dance forms, which were also seen as a way of balancing the consuming nature of the modern world with the health-giving effect of natural, free and flowing movement.

Various forms of natural dance and movement took inspiration from, for example, romanticising ancient Greece. Isadora Duncan (1877–1927) is perhaps the best-known representative of the school that believed in the natural movement. When the American Duncan settled in Paris in 1900, “Greek dance” was already a well-known phenomenon. However, she rose to unprecedented popularity by emphasising the link between body control and the development of spiritual qualities. Duncan’s dance was simple, with everyday movements that defied natural harmony, such as running, jumping, walking and steps from social dances such as the waltz and polka. Although the choreographies were carefully rehearsed, Duncan aimed for a complete impression of spontaneity: the idea of improvised movement that occurs in the moment.

The relationship between dance and sexuality was so strong that women’s public performances in theatres were seen as very dubious. Maud Allan (1873–1956) was a famous performer of “Greek dance” and a contemporary of Duncan’s. In the early 20th century, her most famous solo dance, The Vision of Salome (1903), inspired by Oscar Wilde’s play, shocked theatre audiences. The dance was interpreted as overtly sexual, even “nudity”, as it combined Greek erotic fantasies with dance.[20] Socially, the dancer’s profession was often equated with prostitution, while dance was equated with sexuality and the display of the body. The private salons, a kind of semi-public spaces, were an important support network for female dancers, and enabled Isadora Duncan, for example, to pursue a career as a respectable dancer.[21]

The change in moral codes after the First World War was important for the breakthrough of free dance. Professional dancing was slowly opening up to the daughters of “respectable” families, and the health benefits of free dancing were an important step in this process. Duncan linked dance prominently to a moral lifestyle, including the role of social dancing in education and the health benefits of dancing.[22] Although the solo dancer rose to prominence in various modernist dance forms, performance was not necessarily the main function of dance, but rather dance was practised and taught to others precisely for health and spiritual wellbeing. Michael Huxley sees similar experiences in the writings of many dancers in the 1900s and 1920s. Through dance, something was sought that involved individuality, freedom, naturalness and spirituality in movement, but it was not yet called modern dance.[23]

After the First World War, the role of women in society changed forever as the “new woman” became more involved in the workplace and in political and social events. The modern woman was active and independent, and a new conception of leisure included not only a role as a consumer but also self-fulfilment. Dance and the spontaneous expression it brought with it became an important activity for the new woman, both as an educational and social activity. At the same time, the moral rules relating to sexuality and the body were updated. Dance expression was one way of distancing oneself from outdated gender norms that restricted women’s bodily freedom.

The relationship between natural dance and dance modernism is not unequivocal, as it also contains strong anti-modernist features. In dance, the link with the past represented a return to a society perceived as better and healthier, a time before the harmful effects of technology and urbanisation on the body. Indeed, Ramsay Burt and Michael Huxley point out that this may have led to natural dance receiving less attention in the study of dance modernisms. However, many practitioners of natural dance had little connection with the development of modernist theatre dance.[24]

Natural movement was the antithesis of the new social dances of the period, such as the tango and ragtime (swing dances), which were popular in the 1910s. Their syncopated rhythms and angular movements represented the degenerate body of the urban metropolis against which the new art dance was fighting. The word “modern” also referred to the new social dances, so it was not exclusively associated with art dance.[25]

Cabaret and Charleston as Expressions of Modernism – Josephine Baker

Jazz evolved from blues and ragtime after the First World War in the United States and spread to Europe in the 1920s. The transatlantic touring system of variety theatre ensured that influences moved quickly in both directions and that Black performers in particular sought better pay and more equal work opportunities in Europe, especially after the war.

Josephine Baker (1906–1975) rose to prominence as a performer at La Revue Nègre (“The Black Revue”) in Paris in 1925. Her early performances were based on exoticism and the association of uninhibited sexuality with the Black other, and these racist and caricatured dances were performed for white audiences based on the ideas of white managers. White images of “Africanness” were reflected, for example, in a duet Baker danced with Jo Alex wearing only feathers around her waist and ankles.[26] In the 1930s these themes receded and Baker performed as a singer, took ballet lessons from George Balanchine and danced his choreographies in pointe shoes. Katherine Dunham considered Baker a brilliant and versatile performer in singing, dancing and acting.

Baker’s dances were a meeting place for many different kinds of embodiment. Raised in Saint Louis, Missouri, and later living in Harlem, Baker started as a musical theatre dancer on Broadway, but rose to fame in Europe. She is considered a key figure in the spread of jazz music in France, as Baker was the first to dance the Charleston, a fashionable dance for free and independent women in Paris. In 1920s flapper culture, dance was seen as a way for “the new woman” to be herself and independent in public space. This was also emphasised by the new fashion’s emphasis on straight-line clothing and shorter mid-calf hemlines.

At the same time, in the avant-garde artistic circles of Paris at the beginning of the millennium, ideas about Africa were associated with a positive connotation of freedom and spontaneity.[27] The “primitive” was associated with an experience of authenticity as a counterweight to the bourgeois and rigid culture of modern society. The (white) audiences and critics of the period saw Baker primarily as an exotic and racialised dancer who represented a romanticised “primitive” modernism. In it, dance and the embodied unity it brought were a salvation from the malaise of modern society.[28]

Jazz music was also seen by the (white) public of the period as both “primitive” and extremely modern: at once the thrum of jungle drums and the noise of industrial machinery. Dancing, for example in the Charleston, was perceived as a ritualistic surrender to the strong “primitive” rhythms of jazz. Dance was thus an experience of community and naturalness that had been lost to the degeneration of the modern world.[29]

Readings on Baker’s dance, based on essentialism and mystification, often ignore her skills and achievements. Baker’s dances were based on polyrhythm, which was reflected in the movement of different parts of the body. She was extremely skilled at improvisation, which involved the mastery of certain structures and codes that allowed her to communicate not only with other dancers but also with musicians. Baker’s dancing incorporated Black cultural themes of community and shared history that were linked to pre-diasporic Africa.[30] Baker is situated in a continuum of Afrodiasporic rhythm and expression; as typical of the period, her dance had many Africanisms, or features of African or African American dance.[31] (see Afrodiasporic and Pan-African Modern Dance)

Baker became an instant star in Paris in the 1920s, where she made her debut at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées,[32] the same theatre where The Rite of Spring had had itsscandalous premiere in 1913. African American performers in particular were the subject of much attention in Europe, and critics noted Baker in a way that would have been impossible for example in New York.[33] In the United States, racial segregation caused performers to be treated unequally.

Nicknamed “la Bakaire” in Paris, Baker became not only a famous performer but also a glamour-defying style icon. Baker was also an active civil rights campaigner and anti-racist.[34] In Miami in 1950, for example, Baker refused to perform at a whites-only club until her demands for diversity in the audience were met.[35]

With a few exceptions, Josephine Baker has long been absent from dance historiography, although her popularity and influence on the dance of the period is undeniable. Ramsay Burt suggests that Baker’s invisibility is due not only to the fact that she was a young woman and an African American, but also to the fact that her venues were not the so-called high culture stages.[36] Baker’s dance represented ragtime and variety, which was not given artistic status in the dance discourse of the turn of the 20th century.

Flourishing Dance of the Weimar Republic

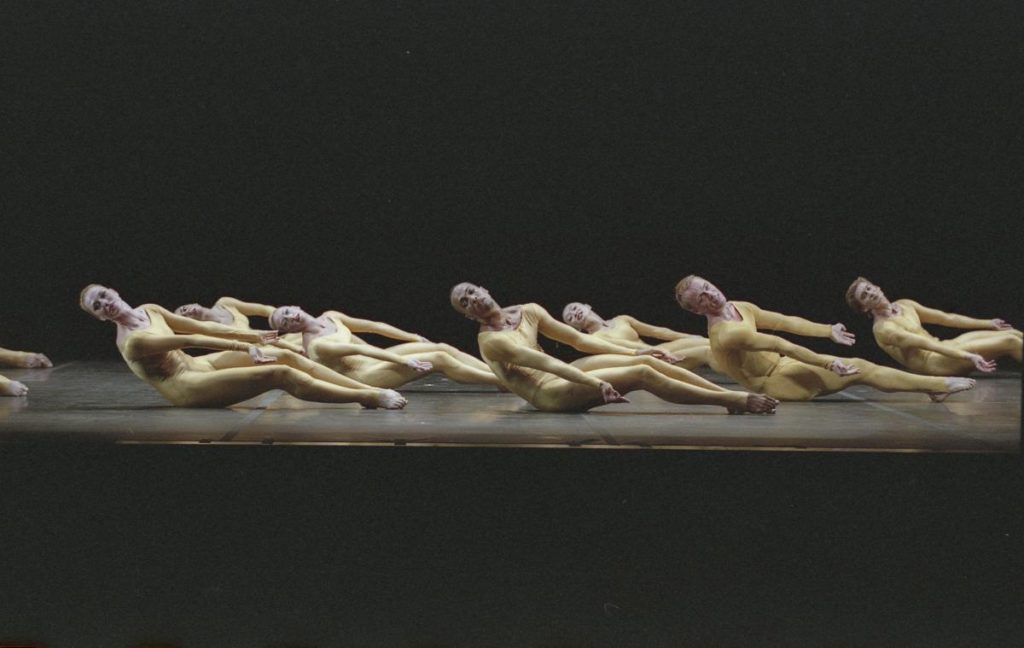

During the Weimar Republic (1918–33), German dance culture was diverse and developed on many kinds of stages. Variety of forms of body culture (Körperkultur), from gymnastics to nudism or various body techniques and forms of dance expression, flourished. Jazz and the new social dances associated with it spread to nightlife. Germany was heavily influenced by international touring, and in Berlin in particular you could see famous dancers from the United States or Paris. Josephine Baker danced the fashionable Charleston in Berlin for the first time in 1926.[37] The Tiller Girls, a group of English origin, delighted audiences with a simultaneously moving dance chorus line, an array of bodies whose movement was like a perfect machine operating with precision.[38] This was a period of great political and economic uncertainty. Kate Elswit describes the polyphonic meaning-making of Weimar-era dance as rehearsing modern citizenship, an experimental art reflecting a highly charged period in which anything was possible.[39]

The new modern dance forms of the period are called Ausdruckstanz (dance ofexpression).[40] The term usually refers to dance forms that developed in the early 20th century, especially in the German-speaking regions of Central Europe. However, the name was given retrospectively, since from the 1910s to the early 1930s, the new German art dance was called, for example, Absoluter Tanz (absolute dance), Freier Tanz (free dance), Moderner Tanz (modern dance), Neuer künstlerischer Tanz (new artistic dance) and Bewegungskunst (art of movement).[41] The term Ausdruckstanz encompasses not only a wide range of very different aesthetics, but also many practical and theoretical approaches to dance. Some of the loose common features among the forms of Ausdruckstanz could be the independence of dance from other arts, the connection of movement to emotional and mental processes and to the cosmos, the central role of improvisation and the role of the dancer as a dance maker.[42]

Ausdruckstanz was only one part of the diverse body culture and dance of the Weimar period, which encompassed a polyphonic set of dance styles and choreographic languages.[43] Dance was strongly present in other arts. In the famous dance scene in Fritz Lang’s Weimar-era silent film Metropolis (1927), the humanoid robot dance combines ecstatic dance with stylised and mechanical expression with the aim of an erotic nightclub performance. The Bauhaus also worked with performance. Oskar Schlemmer[44] introduced dancers dressed in geometric shapes in his Das Triadische Ballett (“Triadic Ballet,” 1922), where costume was a motor for a different kind of physicality: huge swirls of iron wire around the body, golden spheres with no openings for the arms, and long costumes that prevented movement of the knees and hips.[45] Many Bauhaus teachers and students were inspired by Gret Palucca’s dance.[46]

The canonical narrative of German modern dance emphasises the importance of Ausdruckstanz. In the Weimar Republic, however, the various modernist dance forms were performed not only in theatres, concert halls, various private spaces and cinemas, but also in popular cabarets.

Weimar Cabaret

In Germany, the cabarets of the Weimar period were thriving venues, especially in the big cities. The performances consisted of short and varied numbers, including singing, monologues, dancing or pantomimes. Through pungent parody and satire, they dealt with social phenomena and current events. With the end of censorship after the First World War, sexual liberation increased and cabaret performances also began to deal with gender, homosexuality and prostitution. Performances could include nudity. Politics was present in cabaret, and in the last years of Weimar agitprop connected cabaret more strongly to socialism. Politically sophisticated cabaret was often left-wing or left-liberal and therefore fell foul of the National Socialists.[47]

Like many artists of the Weimar period, Valeska Gert (1892–1978) was inspired by the nightlife of the metropolises. Another important influence were the Berlin Dadaists and their avant-garde ways of dealing with violent modern life. Gert had some ballet training at a young age and later studied theatre, but above all she became acquainted with expressionism and its theatre, playing small roles under the direction of Max Reinhardt and Otto Falckenberg. By the mid-1920s Gert already had her own style, which, like early expressionist theatre, focused on movement, gesture and expression, and on the inner state of being as the starting point for art. This reduced but precise expression is evident in her early dances, where a single arm movement can contain a range of emotions from joy to anxiety.[48]

Corporeality was Gert’s way of constructing a stinging social critique in which she mocked social rules and bourgeois values. The caricatured characters in the performances ranged from stereotypical portrayals to satire. The characters often highlighted silenced realities. In Gert’s words: “Because I despised the burgher, I danced all of the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls – the ones who slipped through the cracks.”[49] Perhaps Gert’s best-known work is the chillingly realistic Canaille (“The Prostitute,” 1919). It shows the whole arc of buying sex, from the hip-swinging seduction to the raw sexual act and the woman’s orgasm, all stripped of bourgeois romantic love. Gert also used elements of mass culture, such as circus or boxing, in her performances. Mocking parodies of the Charleston and American variety line-dancing can be found in Variété (1920), a commentary on the commercial stereotype of Americanism.[50]

The precise interpretation of body and facial expressions and the grotesque exaggeration were aesthetically different from other dance phenomena of the period. Gert brought to dance the influences of the theatrical avant-garde, such as the distortion of the grotesque into a caricature, montage, repetition and exaggeration of everyday gestures, and the use of speech and sound as part of the dance.[51] Bertolt Brecht admired Gert’s way of distancing the audience on the dance stage. Gert was a regular performer in Brecht’s cabaret Die Rote Revue at the Münchner Kammerspiel and in his Threepenny Opera (1931).

During and after the First World War, the horrors of war were part of Weimar society, and death was ever-present on many levels. Physically and psychologically crippled soldiers could be seen on the streets after the war as a sign of the crippling of Germany itself. Death was a place (topos) of authenticity and its treatment in the public space extended to art.[52] Valeska Gert’s Der Tod (“Death,” 1922) could even be described as hyper-realistic dance theatre. During the performance, which lasted about two minutes, Gert stood still in silence and embodied death with her upper body and face, with slight changes of gesture, spasms and finally a release of tension. At the time, the work was discussed as direct expression, as death experienced and immersed in by the performer, rather than as imitating (mimesis)or performing of death.[53]

The cabaret performances of Anita Berber (1899–1928) were a combination of the macabre and the erotic. Subjects such as morphine or absinthe were inseparable from the performer’s real addictions. The solo Kokain (“Cocaine,” 1922) lasted seven minutes and, as its name suggests, dealt with the effects of cocaine as a bodily experience. The dancer sometimes moved like an involuntary marionette, with simple steps, between reality and delirium.[54] Berber’s performances included dance from all sides, such as very refined and skilfully performed ballet movements or new social dances like ragtime and Charleston.[55] The performances were too serious, both in their physical expression and in their themes, to be mere light entertainment; they blurred the line between art and variety. At the same time, it remained unclear how much of the movement was actively produced and how much was the result of the dancer’s own addictive experience. As Berber surrendered to the dance, her body appeared strange and distant, and the dancer may not have been fully aware of this in her performance.[56]

After the National Socialists came to power, cabarets considered degenerate were closed and Jewish performers were persecuted. Valeska Gert was also branded as unpatriotic and non-German, because of both her critical art and her Jewish heritage. Gert fled to London and from there to the United States, eventually settling in New York, where he opened her famous cabaret Beggar Bar (1941–45).[57] Social criticism of the Weimar Republic was distant to American audiences, so Gert’s repertoire expanded to include criticism of the Western bourgeoisie.[58]

After the communist uprisings in the United States after the Second World War, Gert moved back to Europe. She performed and opened new cabarets and appeared in several films, including Federico Fellini’s Giulietta degli spiriti (1965). In the 1950s and 60s, Gert’s performances were satires on the National Socialist past and criticisms of post-war West Germany. In the 1970s, Gert appeared on German television talk shows as a strong, unconventional figure in her 80s with black hair and red lips, inspiring the punk movement.[59] Dance artists have also explored the figure of Gert and avant-garde art in their work.[60]

Gert is an example of a dancer who was long outside the canon and whose importance was only really reassessed in the 1990s. Like Josephine Baker or Anita Berber, she belongs to the group of performers whose dance does not fit into the canon’s fundamental idea of a healthy and therefore pure body, promoted by dance art, on which the narrative of modern dance has long relied, not only in Germany but also in the United States.

Free Dance, Dance Education and Movement Choirs – Rudolf Laban

The narrative of the German modern dance canon builds from forms of German body culture (Körperkultur) towards Ausdruckstanz and finally towards the strong and healthy “pure” body idealised by the National Socialists. The central figure in the canon is Rudolf Laban,[61] who was born in Austria-Hungary and studied architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris while taking lessons from a student of François Delsarte. Laban founded a dance school in Münich in 1912 and began to develop the principles of free dance (Freier Tanz) – a dance that would not be based on fixed steps, music or storytelling.

During the summers, Laban’s art school’s experimental and holistic approach to the arts was at the heart of the Monte Verità community.[62] Located in the Swiss Alps, this alternative lifestyle (Lebensreform) community sought a return to a simple life and a connection with nature and the self. The idealistic spirit of Monte Verità is reflected in the ritualistic Sonnenfest (“Festival of the Sun”) built by Laban in 1917, which began with a sunset dance, continued at midnight with a dance of torches and moonlight demons, and ended at dawn. The 12-hour outdoor performance included a series of movement choirs, a kind of participatory dance, where the energy created by dancing together was central.

Laban’s teaching in the early 1920s was not based on copying steps or postures, but on the dancer’s ability to work with different elements. He valued the dance of Isadora Duncan for its fluidity of movement and composition that maintained an organic continuity.[63] Laban’s free dance was based on exploring the body’s functions and movement through improvisation. Like many of his contemporaries, Laban was inspired by various mysticisms, including theosophy, which influenced his understanding of energy. In German modern dance, the intuitive and irrational world of the “primitive” tribes, believed to be found in the memory of each body, was widely admired.[64] It was seen as a counterweight to the sensory and emotional numbing lifestyle of modern society.

Rhythm was central to Laban, especially the rhythmic movement of the body (Schwung). The body’s inner rhythm became more important than the rhythm provided from outside by the music. Movement could be associated with silence or poetry, for example. Rhythm was believed to connect the dancers’ bodies through vibration in the movement choirs and to build a connection between the bodies and cosmic forces. Laban also sought to understand the nature of movement. Time, weight, space and energy were qualities of movement that contained information about movement and its “natural” characteristics. The dancer had to develop awareness of the different aspects of movement to a level that went beyond the everyday.[65]

In the 1920s, the popular movement choirs were central to Laban’s conception of dance art. They were strongly associated with health and dance education, as dance was seen as belonging not only to professionals but also to ordinary citizens. The group exercises and body awareness exercises did not require participants to have any prior knowledge of dance. In addition, the ritualistic nature of the movements brought to the choreography the characteristics of folk and social dances by building a sense of community. In German modern dance, community also fought against the degenerating influence of the modern world.[66] The communal experience through participation was stronger than when just watching dance.

The culmination of Laban’s movement choirs was the Festzug der Gewerbe (“Parade of Trades”) in Vienna in 1929. The procession was attended by 10,000 performers, from dancers to actors. Among them were blacksmiths, tailors and bakers. The dance was inspired by the rhythms and movements of different types of work. Laban did a lot of choreography for festivals that became popular during the period, which were often one-off large-scale dance events. Festivals also challenged the perceived bourgeois conventions of theatre by blurring the distinction between spectator and performer, and Laban’s movement choirs and activities with dance enthusiasts were well suited to this purpose.[67] Another key interest in Laban’s artistic work was the theatrical forms of dance that combined dance and pantomime.[68]

Laban’s Theories and Labanotation

Laban’s work in dance education and art progressed in parallel with his theoretical understanding of movement. A complex theory of movement developed over decades of research. These theories combined the experiential nature of dance with systematic observation and analysis of movement. The book Die Welt des Tänzers (“The World of the Dancer”), published in 1920, opens up Laban’s ideas on the basic principles of dance and movement. Although structured more as a collection of notes than a systematic treatise, the book had a strong influence on dance and its teaching, particularly in Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom. The book also established Laban as a leading figure in the new dance phenomenon developing in Germany.[69]

Laban’s term kinesphere refers to the space surrounding the body. Various geometric constructions – a cube, an octagon or even an icosahedron with 20 different surfaces – made the kinesphere visible in different ways and allowed it to be explored in movement. At the same time, the forms symbolised the relationship between nature and dance, with the aim of restoring the relationship between humans and the cosmos.[70] Laban did not completely deny the ballet tradition, but sought a new relationship with it. As early as the 1920s, he articulated his theories, including his spatial theory of movement (Space Harmony or Choreutics), which was based on the geometric system of ballet and sought to develop it further. In 1926, Laban presented his system based on the dynamics and rhythm of movement, called Eukinetics(from the Greek eu, good, and kinesis, movement). Its aim was the harmony of movement: a balanced connection with the world through dance.

The project to notate movement began as early as 1924. As the movement choirs grew larger and larger, notation became an important tool in their planning. Eventually, in 1928, the system became known as kinetography or Labanotation. Laban wanted the system to be simple, but suitable for notation of all types of motion. Labanotation symbols could be used to write down movement, including all body parts, as well as the spatial characteristics, dynamics and rhythm of the movement.

Working with ordinary citizens made Laban aware of the link between the choreographer’s work and the dancers’ skills, and this motivated him to develop a training system for dancers. For research and the training of dancers, teachers and notators, Laban established schools and artistic research institutes. Many of them provided practice for movement choirs.

In the 1940s and 50s, Laban’s research became increasingly theoretical, while his artistic activities declined. Effort theory, developed in the 1940s, extended earlier studies of dance towards the analysis of all kinds of movement. The theory is based on the notion of dynamic rhythm as the basis for all human activity, both physical and mental. The intrinsic motivation to move, for example as a result of an emotion or thought, is seamlessly linked to the physical movement actually happening. Effort theorysees movement as a transformative and dynamic continuum that can be analysed through four elements: space, force, time and flow. Each element has two opposite extremes between which dynamic variation occurs.

Effort Theory

- Weight is the body’s dialogue with gravity and the environment, with the “light” masking the earth’s gravitational pull and creating an ethereal quality of movement, while the “strong” resists it, for example when lifting a heavy object.

- Flow is a continuous movement of energy. It is divided into “free,” where the body follows the flow and momentum of movement, like when sensing the inertia while spinning with outstretched arms. “Bound” movement, on the other hand, is conscious and controlled, and can be stopped at any time, such as moving an easily broken object or moving in a pitch-dark space.

Space refers to a way of relating to the spatiality of a movement, and is divided into “direct” and “indirect.” In the first case, the direction of movement is clear and controlled, such as pointing a finger or hammering a nail. In contrast, the direction is constantly changing and mutating, such as tying a shoelace or walking in a crowd.

Time is more an internal and intuitive relationship with time than a measurable value. Time is “sustained,” for example, when dragging one’s feet or in seductive gestures that stretch the duration of a movement. “Sudden,” in contrast, is associated with haste and acceleration, such as catching a falling object in mid-air or a startle.[71]

InEffort theory, each movement is the result of the simultaneous action of several components, and different combinations produce different qualities of movement. These movement patterns, in turn, are related to the personality of the mover. Laban developed the system in collaboration with engineer Frederick C. Lawrence and assistant Lisa Ullmann by analysing body movement in industrial work. The information it provides relates not only to the expressiveness of movement, but also to its functionality and efficiency.[72]

Laban’s movement analysis and notation system have spread worldwide. Several systems based on Labanotation have been developed in countries such as Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States. The Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance in London is not only an important centre for documentation and research into Laban’s legacy, but is also renowned for its dance training.

Dynamic Body and Space – Mary Wigman

Mary Wigman’s (1886–1973) career as a dancer, choreographer and teacher began to develop immediately after the end of the First World War. Like Laban, she saw dance as a primary, independent art, not subordinate to music or narrative. Wigman had studied at the Institut Jaques-Dalcroze (1910–12) (see Hellerau and Transnational Modern Dance), where she was introduced to improvisation. However, she felt that Dalcroze’s way of tying movement strictly to music limited her expression, and to emphasise movement she became Laban’s student in the Monte Verità community. Later, both Wigman and Suzanne Perrottet, a former assistant of Jaques-Dalcroze, assisted Laban in the systematic analysis of movement and the development of its theories.

The Dalcroze Principles

The basic idea of Dalcroze Eurhythmics or rhythmic gymnastics (also Dalcroze method) was to make music visible through the movement of the body. Dalcroze saw music education as a spiritual and physical cultivation of the body and soul as a whole. Each student had a unique heartbeat rhythm, and therefore each body responded differently to music. The first step of the method was listening, focusing on the rhythms within the body and the music, as awareness of rhythms was the pathway to the release of personal expression.[73]

The exercises were based on the structure of the music, not on the interpretation of the musical expression. They included foot rhythm patterns, tapping, moving through space at different speeds and dynamics, or responding to the sound of the piano with movement, stops or changes in movement. In exercises requiring coordination, one hand could move in 4/4 time and the other in 3/8 time. Exercises were always performed to the music, never against the rhythm of the music. In addition, practice was group work – duets, trios, larger groups moving together, in canon, in different rhythms, etc. – as opposed to the individual performance of ballet, for example. Individual expression was important to Dalcroze, but as part of a community. Exercises could be done both neutrally, i.e. emphasising the technical side, or with stylistic and expressive elements, resulting in choreographic compositions, plastique animée.[74]

Dalcroze’s way of understanding music and movement as expressive elements had a decisive influence on the international development of many dance modernisms. His Hellerau school was visited by Sergei Diaghilev and Vaslav Nijinsky, for example, who used eurhythmics to help him work with Stravinsky’s music in The Rite of Spring.

During the First World War, Mary Wigman moved with Laban to Zurich, in the Swiss Neutral Zone. There, the Cabaret Voltaire, founded in 1916, became the headquarters of early Dada, with its multi-artistic stage as a playground that challenged the conventions of art. In addition to poetry, also drama, action, dance and puppetry were the subjects of anarchist experimentation by the Dadaists. Dada was a reaction to the shock of the First World War, and the Dadaists strongly questioned the institutionalisation of art, its distance from real life and the role of the individual in art. They were counterbalanced by collective action, deconstruction, shocking events, chaos, satire and irony. Later, Dada’s influence was central to performance art, happenings and also to Judson Dance Theater’s ideas about everyday life as dance or about the self-consciousness and self-irony of dance.[75]

Many Laban’s students regularly attended Cabaret Voltaire events, notably Suzanne Perrottet, Claire Walther and Sophie Taeuber. Wigman began to use the term Absoluter Tanz (absolute dance) to describe the bright and simple dance she developed, in which neither costumes nor lights adorned or concealed the dance’s imperfections. She said the term comes from Taeuber’s performances, where, like in other Dada dances, the simple gestures and movements of the dance became central.[76]

Wigman focused on dance as a completely independent element and an all-encompassing dance movement. In her dances, Dada can also be seen in the use of masks and costumes, as in the solo Witch Dance (Hexentanz). The first version dates back to 1914,[77] but the final form of the dance was sketched in 1926, with Wigman dressed in a cape-like garment and wearing a mask inspired by Japanese Noh theatre. The dance takes place both in silence and to the accompaniment of various percussion instruments such as cymbals. The masking of the face helps the dancer to enter an altered consciousness and the grotesque figure of a witch.[78] Wigman’s use of different ways of covering the body with masks, robes, capes or contrasts of light and shadow took the attention away from the body and into the movement itself.[79] The use of percussion instruments limited the musical element, which for Wigman was primarily a dynamic content, not a linear source of order or dramaturgy.

In the dance, the figure of the witch led Wigman towards a metamorphosis in which she indulged in “some kind of evil greed I felt in my hands which pressed themselves clawlike into the ground as if they had wanted to take root.”[80] For Wigman, this altered way of being and experience (Erlebnis) was the essence of dance. The dancer was outside herself in an ecstatic state of being, in another reality, while something from within the dancer was transmitted through this bodily way of being. The dancing body was a multi-layered reality, composed not only of concrete but also of psychological and emotional elements. The relationship between the dancer and the audience was described by Wigman as “a fire dancing between two poles.”[81] Sondra Fraleigh reads this as a living kinetic connection, an inter-bodily intersubjective experience. The dancer dances the bodies of all that exist, reaching towards a universal humanity, but at the same time she is unique as an individual.[82] Wigman’s dances expanded our understanding of the expressive possibilities of dance, while the shared experience also questioned perceiving dances through an intellectual communication.

Wigman’s dance was seen as more immediate and instantaneous than Rudolf Laban’s art.[83] For Wigman, the experiential nature of dance contained a passion similar to that expressed in the writings of contemporaries Isadora Duncan or Loïe Fuller. However, some of Wigman’s dances were darker in nature, with characters such as witches, enraged spirits or demons.[84]

Many early modern dance forms reflected nationalism in several ways. The idea of a national identity was present in the American SelfofIsadora Duncan’s dances, while Wigman’s dances, like Laban’s, reflected the (mythical) “Germanness” of the period. The existence of a kind of national essentialist identity was expressed in the dances, for example, as utopias of community, a universally understood Germanness and the “German soul” that Wigman danced.[85]

Mary Wigman’s Methods and International Influence

Wigman approached dance as a strong mental and emotional exercise. The work was based on a series of different ways of moving, such as shaking, swaying, twisting, undulating, falling or reaching. These served as engines of embodiment and helped the dancer to establish contact with her inner movement and her own way of moving.[86] Improvisation was central not only to Wigman’s performances and choreography, but also to her teaching, as both technique and composition were taught through improvisation. Wigman also wrote prolifically about her theories and her vision of an evolving modern dance.[87]

Wigman had a very special relationship with space. She experienced it as sensual and immediate and said she could feel the touch of space on her skin. On a symbolic level, space represented the cosmos.[88] Both Laban’s and Wigman’s thinking about movement in space (Raum) was well developed by the 1920s. Wigman’s dance was special because of its kinetic and ecstatic energy. In her dance she was a dynamic force rather than a recognisable human being: a spatial, genderless and faceless energy, a kind of “figure in space” (Gestalt im Raum).[89]

At the same time, for Wigman, physicality was only the first step in composition. Each dance required its own form and structure, which in turn depended on expression and emotion: the dance was an external form of inner feeling.[90] The structure of a dance had to be extremely carefully worked out, clear and simple, so that the content was conveyed through it. This precise form contributed to allowing the performer to indulge in the ecstasy of dancing. In 1933, Wigman summed up her ideas about dance

Dance is the unification of expression and function,

[91]

Illumined physicality and inspirited form.

Without ecstasy no dance! Without form no dance!

Wigman rose to fame as a solo dancer due to her dramatic and profound use of the body. She is the best known of the many solo dancers of the Weimar Republic who developed and disseminated Ausdruckstanz, with a widevariety of styles and varying dancing skills, and toured extensively in Germany and abroad.[92] It was not central to Ausdruckstanz toclassify dancing stylistically, to develop unchanging methods and techniques, or to build a canon with a repertoire of specific choreographies. Since there are relatively few descriptions or other documentation of the dances themselves, reconstructing individual dances is challenging. In the 1920s and 30s, German modern dance was a vibrant and globally significant phenomenon. It was more like a dynamic and mutable system, spread through the performance and teaching of dancers, than a one-way style seeking a particular tradition.[93]

In the early 1920s, Wigman began to create not only solo performances but also group choreographies for female dancers, whom she trained at the school she opened in Dresden.[94] While working as Laban’s assistant, Wigman had been involved in directing popular movement choirs, but her only work for large crowds was Totenmal (“Monument to the Dead,” 1930).

The Dresden central school, which operated in 1920–42, was an important centre for modern dance in Europe. At its peak, the school had 11 branches, where nearly 2,000 dancers studied in the early 1930s, many of them international students.[95] With them, Wigman’s methods spread around the world.[96] The influence of Wigman’s dance also extended to butoh, as butoh pioneer Kazuo Ono and the artists Eiko and Koma studied with Wigman’s followers. (See Butoh’s Revolutionary Aesthetics and Influence on Contemporary Western Dance) Also a significant number of students came to Laban’s schools from abroad. During the interwar period, schools were established all over Central Europe. In 1927, for example, there were nearly 30 Laban schools in Germany, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland.[97]

Following the success of Wigman’s first United States tour, the New York Wigman School was founded in 1931 at the height of Wigman’s international career and long-time student Hanya Holm was sent to head the school. The heated debate surrounding Wigman’s collaboration with the National Socialists eventually led to the school’s name being changed in 1936 to the Hanya Holm Studio.

Dance in National Socialist Germany

After the National Socialists came to power in 1933, the Ministry of Culture began to emphasise the “German character” of dance. Cabaret culture was thought to be degenerating and, like many other modernist art forms, was largely declared a decadent art form and censored. Jewish performers were persecuted and many fled to places such as England, the United States, Austria or France. However, several forms of Ausdruckstanz were harnessed by the National Socialists, by pruning away inappropriate aesthetics and content. Such collaboration was possible in part because of the fear and resistance to the modernisation of the society associated with early modern dance at the turn of the twentieth century. Dance sought salvation through the natural body, and the same utopian idealisation of the “healthy body” was part of the discourse of fascism.[97] The heterogeneous and vibrant dance scene of the Weimar period was considerably reduced in size. Under National Socialism, the unifying term “German dance” (Deutscher Tanz) was used, with a nationalist and racist connotation.[99]

Lilian Karina and Marion Kant describe the period of National Socialism as a triumph of mass opportunism. Few dance makers actively opposed National Socialist values or showed any sympathy or awareness of the gravity of the situation. The actions of important German dance makers are shrouded in a veil, as there is little mention or links with National Socialism in biographies of Laban, Wigman, Gret Palucca or Harald Kreutzberg. It was only in the 1980s and 90s that the almost taboo role of modern dance in the activities of the National Socialists began to be explored.[100]

Rudolf Laban played a key role in the reorganisation of dance under National Socialism. While working for the Ministry of Culture as the head of the Germanstage dance (Deutsche Tanzbühne), he designed the basis for dance education at the Deutsche Meister-Stätten für Tanz (German Masters’ Institute for Dance), which began its work in 1936. Laban codified improvisation exercises and created a new kind of dance curriculum. Wigman, Palucca and Berthe Trümpy expelled dancers and teachers of Jewish origin from their schools as soon as the National Socialists came to power, even before expulsion became compulsory. In July 1933, Wigman and her successors joined the educational and cultural organisations set up by the National Socialists, and Wigman encouraged all graduates of her school to do the same. She also agreed to have the curriculum of her school adapted to the requirements of the Ministry of Culture.

The harnessing of body culture for National Socialist purposes as a massive group exercise can be understood from Leni Riefenstahl’s film Fest der Schönheit (“Festival of Beauty,” 1938). In it, thousands of Aryan women gymnastically perform in unison and with discipline in the Olympic stadium in Berlin. In the film, gymnastics serves as propaganda for a utopian, purified community centred on a strong, controlled and agile body.[101] Laban’s well-known statement about dance belonging to everyone – jeder Mensch ist ein Tänzer; everyone is a dancer – became a call for almost compulsive group exercise,[102] which glorified athletic embodiment in line with National Socialist ideology.

Wigman sought support for her work from the Ministry of Culture and was even prepared to make artistic concessions to obtain it, but stressed that her art was separate from politics.[103] However, in her book Deutsche Tanzkunst (“German Dance Art,” 1935), Wigman describes how the focus of her dance shifted from universal experience to support National Socialist ideas of the “ordinary” people (Volk).[104] The ideas of many dance makers about “German dance” were disseminated through publications funded by the National Socialists. Goebbels’ Ministry of Culture funded dance art and organised dance festivals (1934, 1935). These culminated in the opening of the 1936 Berlin Olympics, with the participation of hundreds of dancers, including Wigman and Kreutzberg. At the last minute, the movement choreographed by Laban, Vom Tauwind und der Neuen Freude (“Of Spring Wind and New Joy”), was removed from the repertoire because of its supposedly dubious content.

The dance curriculum Laban built was implemented until the end of the Second World War, long after he fled Germany in 1937 after falling out of favour with the Ministry of Culture. Laban moved first to Paris and finally to England in 1938. Wigman also fell out of favour and gave her last solo concert in 1942. She abandoned her dance school, moving first to Leipzig and in 1949, to West Berlin.

After 1936, the Ministry of Culture emphasised lighter art dance and wanted to break away from Laban’s intellectual dance.[105] For Goebbels, dance was all about the presentation of beautiful female bodies.[106] In 1940 he instructed the dance department to break away from political and intellectual, doctrinaire dance: “Dance must address the senses and not the brain. Otherwise it is not dance any more but philosophy. Then I would rather read Schopenhauer than go to the theater.”[107] In addition to problems and war, there was a need for more entertaining content. Ballet was becoming increasingly popular and was seen as a suitable form of entertainment. Folk dances also received a great deal of state support, as they were perceived as being close to the people, as their name suggests.[108]

Susan Manning argues that the collaboration between modern dance makers and National Socialists was partly rooted in a similar (utopian) ideology of the early twentieth century concerning an alternative lifestyle in which community and body culture were keys to escape from modern industrial society. The changing political and economic circumstances of the Weimar period and, finally, the depression of the 1930s drove dancers to seek continuity in the support provided by the National Socialists. Scholars disagree on how much of the collaboration stemmed from shared political perspectives and how much from the pursuit of economic interests. At the same time, the confusing bureaucracy of the Ministry of Culture was conducive to a cunning tactic of promising dance makers opportunities to work independently, while constantly changing policies prevented dance from establishing itself along the paths envisaged by the makers.[109]

Early Dance Theatre – Kurt Jooss

Like many dancers, Kurt Jooss (1901–79) went into exile with his group after the National Socialists came to power in 1933, because he did not want to expel the Jewish members of his group. Ballets Jooss toured extensively, particularly in Europe and the United States. Its base was eventually Dartington, England, where The Jooss–Leeder School of Dance, co-directed by Jooss and Sigurd Leeder, was established for the period 1934–39. Rudolf Laban also fled Germany, eventually ending up in Dartington in 1938. During the war, people in England became increasingly interested in dance education, and by the 1940s Laban’s expertise in the field was widely recognised, but Leeder and Jooss were sent to an internment camp in 1941. On their release, they moved Ballets Jooss to Cambridge, where a new repertoire began to be rehearsed in 1942.[110]

Having studied under Dalcroze and Laban (1920–22), Jooss founded his first dance company in 1928 while he was head of the dance department at the Folkwangschule in Essen. The group came to international attention in 1932 when it won the Paris International Choreography Competition with Jooss’s iconic choreography The Green Table. The politically left-wing, pacifist work is perhaps the most famous dance work of the Weimar period. The Green Table is a depiction of the experiences of the First World War, a kind of modern Dance of Death in which Jooss himself danced the role of death, appearing in the form of a skeleton. It is also a symbolic representation of the causes of the First World War. By showing how businessmen and imperialists profited from the war, the work strongly reflects the period’s perception of the absurdity of war.

Jooss is known as the developer of early dance theatre (Tanztheater). The concept was introduced in the 1920s, when Jooss and Laban were interested in modern dance as part of larger-scale theatres and opera houses. This was in contrast to Wigman’s ideal of absolute dance, which sought dance’s independence from both institutions and narrative. In the 1970s, however, Ausdruckstanz was seen as an important precursor to Tanztheater, partly from a very nostalgic point of view and without a clearer understanding of its history or methods.[111]

Jooss was interested in combining dance movement with action, that is, with dramatic narrative, where gestures played a central role. Jooss was also interested in developing technique training. The Jooss–Leeder technique incorporated elements of classical ballet and Laban’s movement principles and exercises.[112] In the 1935 Ballets Jooss programme notes, the group’s aim is described as a dance whose “language is movement built up of forms and penetrated by the emotions.”[113] Moreover, Jooss’s company had a very particular way of dancing together. Ballet in Britain during this period was based on a hierarchical division into principal dancers and chorus, which was also the basis of the choreographic structure. Jooss’s company and its choreographic language, instead, emphasised the collaboration of the dancers rather than the skills of the individual dancer.[114]

On Ballets Jooss’s first major tour in 1933, the company’s modern repertoire attracted attention in London, Paris and New York. At the same time, critics found it difficult to place it in relation to ballet and modern dance. Jooss’s work is situated in interesting spaces between the technique of classical ballet and the expressive elements of dance. On the one hand, it is a dance entity in its own right, but also a fusion of dance and theatre. The movement language, on the other hand, consists of dance as action but also includes form-focused, formalistic movement.[115]

Ballets Jooss performed the choreographer’s works around the world. The Green Table, for example, was danced more than 3,000 times on the company’s numerous international tours, but was not performed for German audiences until after 1951.[116] Jooss’s student Pina Bausch dances in recordings of the work from 1963 and 1967.[117] Later, Bausch developed her own form of dance theatre and became a world-famous choreographer. Inaddition to Bausch, dance theatre in West Germany was developed by artists such as Johann Kresnik, Susanne Linke and Gerhard Bohner, whose style is described as socially critical. Their counterparts in East Germany were Tom Schilling and Arila Siegert. All of these artists had studied under an Ausdruckstanz dancer.[118] Swedish dancer Birgit Cullberg (1908–1999) also studied with Jooss at Dartington in 1935–39. She worked with dance theatre through satire and humour, creating her own style, and in 1967 founded the well-known Cullberg Ballet.

Interaction Across the Atlantic – Hanya Holm

Cultural exchange between the United States and Germany was already significant in the 1920s and 30s. American dancers travelled non-stop across the Atlantic to Germany to study, and this very close interaction was only interrupted for the duration of the Second World War.[119] In 1928, Harald Kreutzberg and Yvonne Georgi performed in the United States on one of their many tours. Kreutzberg had worked not only with Mary Wigman and Rudolf Laban but also with Max Reinhardt, while Georgi had studied with Dalcroze and Wigman. Wigman’s many US tours in the early 1930s increased interest in German modern dance techniques. The international interaction of dance is thus more extensive than historiography often suggests, and Susan Manning even speaks of Americanised forms of Ausdruckstanz.[120]

Hanya Holm (1893–1992), a student of Mary Wigman, was sent to the United States as a representative of the Wigman School to spread her mentor’s working methods and artistic principles in 1930. Holm worked extensively as a teacher and choreographer, developing her vision of modern dance art. As a representative of German dance, she did not fully fit the narrative of modern dance as an all-American phenomenon. Holm was often labelled an “outsider” who had shaped her dance to reflect the American spirit and temperament.[121] As word of Wigman’s links with the National Socialists spread, Holm separated her dance from politics: “A racial question or a political question has never existed and shall never exist in my school. In my opinion there is no room for politics in art.”[122]

The codified technique and dance composition of American modern dance were the antithesis of Wigman’s ecstatic improvisations and emotionalism. In Germany, dance was often centrally associated with an educational vision in which dance was for everyone: through it, the healed body, mind and spirit awakened to a better and fuller life.[123] Initially, Holm’s teaching also involved amateurs and professionals practising together, and dance was a shared practice of community (Gemeinschaft) and experimentation. Gradually, teaching changed to meet “American needs,” in practice emphasising individual skill and repetition. However, Holm insisted on improvisation when exploring themes such as tumbling, jumping and spinning, or in composition, such as the balanced relationship between the dancer and the space.[124]

Holm continued to implement her mentor’s artistic principles throughout her career. Like Wigman, she saw each choreography as a different whole with its own quality, form and vocabulary of movement. That is why she did not develop a codified technique during her career. Holm was particularly interested in movement as a lived experience, its abstract kinetic dimension and space. Tresa Randall has shown how Holm transformed her dance education goals into artistic outputs, thus continuing Wigman’s communal legacy in performance and in the American context to reach for a true “American spirit.”[125]

In 1935 Holm completed her first dance concert, but it was not until 1936 that her group, the Hanya Holm Company, made its debut on the professional stage. City Nocturne (1936) and Trend (1937) depicted the horrors of modern metropolises and the healing power of community, while Dance of Work and Play (1938) celebrated “primitive” rhythms and togetherness. Holm also choreographed a dozen musicals, including Kiss Me, Kate (1948) and My Fair Lady (1956). Work on musicals – in theatrical, commercial and popular settings – is often separated from Holm’s “artistic” work, although she used the same methodologies on Broadway as she did in her independent work. The use of improvisation and the understanding of choreography as the result of organic movement and collaboration also influenced the form of the musicals: the choreography was not a separate and intrusive entity but part of the organic fabric of the performance.[126]

Holm’s work challenged many boundaries. Not only did she move between the artificially differentiated fields of “German” and “American” modern dance, but she also worked freely with her own choreographies and commercial musicals, challenging both the boundaries between different artistic disciplines and the relationship of art to popular culture. New interpretations suggest that Holm’s movement outside the boundaries reflects the diversity of dance modernism more broadly.[127] Yet, the inputs of “serious artists” working in the field of popular culture, mixing so-called high and low culture – like George Balanchine’s choreographies for musicals – was for a long time systematically ignored as part of dance modernism.[128]

Development of White Modern Dance in the United States

Of the early practitioners of white modern dance in the United States,[129] the German Hanya Holm was the only one to come from outside the Denishawn School. Founded by Ruth St. Denis (1879–1968) and Ted Shawn (1891–1972), Denishawn School formed Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, the key figures of the American modern dance canon. Holm was also the only one of them who was not born in the United States. In the 1920s, Denishawn’s alumni rebelled against the group’s activities, leaving the school and devoting themselves to their own artistic work.

Denishawn

In the early years of the 20th century, Ruth St. Denis had become known for her orientalist dances, based on the practice of Delsartism.[130] (see The Long History of Orientalism) The United States had a strong tradition of variety dance[131] and performances combining various short numbers were a popular form of entertainment from the early decades of the 19th century. St. Denis’ orientalist performances with ornate costumes were a perfect fit for vaudeville shows and tours, which made the dance economically viable. In private salons and theatres, St. Denis was able to enter by emphasising that dance was a ritual and spiritual practice, thus distinguishing it from the sexualised dance numbers of vaudeville, which could also have orientalist overtones.[132]

St. Denis, with her husband Ted Shawn, founded The Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in Los Angeles in 1915, which grew into a network of schools across the United States. Denishawn’s performances were visualisations of music, often plotless compositions in which group formations were central. From a contemporary perspective, their orientalism raises questions of cultural appropriation.[133]

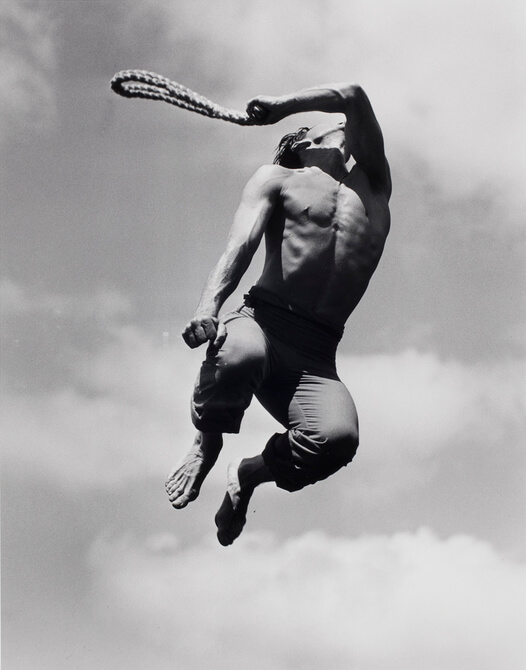

The school closed in 1931 when Shawn and St. Denis divorced. However, Shawn wanted to develop an American modern dance form exclusively for male dancers and established a dance training and performance centre on a farm he bought in Massachusetts. The place was named Jacob’s Pillow and is still a prominent part of the dance scene in the United States. Shawn had a positive impact on male dancing in society. However, he did so by portraying men in foreign cultures from Asia to Europe, rather than in the United States, while reinforcing both cultural stereotypes and traditional gender roles.[134]

From the 1930s onwards, white modern dance developed significantly in the United States, particularly in New York. Central to the period was the construction of white modern dance as an American art form. Its canon was largely based on each choreographer’s individual way of dancing: a personal style and a codified movement language in which the exploration and renewal of movement form was central. In this formalist approach, choreographed movement sequences and dance techniques based on repetition of movement were seen as more important than improvisation. Moreover, the distinction between amateurs and professionals was clearer than in German modern dance forms, which also valued dance as a communal activity.

Various modern dance techniques were developed to train dancers and familiarise them with the formal language of each choreographer. Many modern dancers sought financial security in teaching, as the financial risk of independent performance was high. Unpaid internships, the use of the rehearsal studios of mentors and colleagues, or the possibility of renting a theatre at a reduced rate on certain days of the week for dance concerts were the lifeblood of independent artistic work.[135]

A summer course organised by the Bennington School of Dance in 1934–42 brought together dance professionals and amateurs and made a significant contribution to the development of modern dance in the United States. In addition to providing dancers with the opportunity to learn dance techniques, it also enabled choreographers to work artistically with the support of the festival.[136] Graham, Humphrey, Weidman and Holm were driving artistic forces in Bennington. It was Holm’s school in New York and her work as a teacher at the Bennington summer course that introduced the influences of German modern dance to the United States.[137]

Revolutionary and Leftist Dance – Anna Sokolow

Strongly committed to the labour movement, Helen Tamiris and Anna Sokolow were downplayed in the American modern dance canon during the anti-communist era. They represented a politically radical form of dance emerging from socialist circles in the 1930s, leftist dance, which saw dance through leftist values. Its aim was to promote social change through dance.

The phenomenon was called revolutionary dance, and it was constructed as left-wing ideology and activism sought a physical form.[138] Indeed, the methods of improvisation in German modern dance and their educational and communal origins were of particular interest to left-wing dance practitioners in the United States, and are said to have influenced Black modern dance as well.[139] Revolutionary dance had the task of reflecting social problems, such as class divisions or issues of equality, and of addressing the realities of the working class. The dancer Jane Dudley (1912–2001) described how mass dancecould express revolutionary and meaningful ideas through simple but clear group movements. Movement choirs involving large crowds required little training for the individual dancer, but with good direction they were an opportunity to embody revolutionary ideology.[140]

Founded in 1932, the Workers Dance League (WDL, later the New Dance League) brought together revolutionary dancers and dance groups and provided dance education and performance opportunities. Among the revolutionary dancers were many members of the Graham and Humphrey companies, such as Anna Sokolow (1910–2000), whose strong and charismatic performance was praised by critics of the time.[141] Sokolow was the child of Russian Jewish immigrants who grew up in New York. She danced with the Graham company (1930–39), but was also an active member of the WDL. Sokolow founded her first dance group in 1933, and in 1935 it was permanently renamed Dance Unit.

Sokolow’s works highlight individual stories that expand to address the ills of society.[142] Strange American Funeral (1935) exposes the injustice of capitalism by recounting the accidental death of a migrant worker in a steel mill. The work depicts the chaotic feelings of despair in the community. The programme notes describe in detail how Jan Clepak was “a worker who was caught in a flood of molten ore – whose flesh and blood turned to steel”[143] Case History No. – (1937) embodies the life of a marginalised youth on the street. Sokolow herself danced this solo work, but surprisingly the critics read the character as male, while the manuscript does not give a reading of the character’s gender.[144]

Revolutionary dance ranged from communist propaganda (agitprop) to works that more lightly reflected leftist values.[145] At its most radical, it used extreme emotional expression to break away from the formal language of the modern dance canon, in which dance technique played a central role. Body-to-body emotion was a powerful tool of influence, the theory of which Mark Franko succinctly describes as “without emotion, no revolution.”[146] Many dance critics were dismissive of revolutionary dance and found these anti-modernist works artistically unattractive.[147] In addition to the political message, Sokolow was working on the emotional load of the theme. In the mid-1930s she collaborated with the Group Theatre and became familiar with Stanislavski’s ideas on emotional memory and inner impulses, which became part of Sokolow’s choreographic process.[148]

In the 1950s, Sokolow’s choreography took a more abstract turn, for example in Lyric Suite (1953) and Rooms (1954), which brought the alienation of urban life to the stage. In addition to a universal level, her works often have a very human approach to their subject matter. Rooms, for example, allows for a wide range of readings, from the loneliness of the urban metropolis to a love affair told from a queer perspective.[149] Dreams (1961) and Steps of Silence (1967) dealt with the Holocaust. Hannah Kosstrin points out that the history of dance has often ignored leftism in Sokolow’s works and concentrated on this later phase that deals with modern society.[150]

As modern dance developed rapidly in the United States in the 1930s and 1950s, left-wing dance networks actively interacted with well-known dance makers. The studios of active modern dance practitioners (Graham, Humphrey and Weidman, Holm, Tamiris) were also frequented by left-wing dancers, and many dancers were active in both networks. However, left-wing dancers often perceived the technicality of American modern dance as bourgeois, and its formal language did not necessarily lend itself to radical choreographies of oppression, hunger, rebellion, brotherhood of nations, etc.[151]

Anna Sokolow managed to move interestingly between many frames of reference. She did not abandon her training in modern dance, but incorporated elements of Graham’s formal language into her choreographies, while working with Graham raised her to the status of an artist worthy of consideration by critics.[152] In contrast, the formal language of Sokolow’s work appealed to modern dance audiences,[153] while the themes of everyday life were easily accessible to audiences seeking a leftist value system. Her group performed not only at working-class events but also for a variety of audiences in Broadway theatres and Jewish cultural centres. Even Sokolow’s Jewish origins seemed to have lost ground in the United States, where Jews were not considered “white” until after the Second World War.[154]

Dance between Individual and Group – Doris Humphrey

Instead of Denishawn’s far-flung themes and exoticising dance, modern dance makers sought themes from American reality. Doris Humphrey (1895–1958) was also interested in American society and the individual experience as a starting point for her dances:

I believe that the dancer belongs to his time and place and that he can only express that which passes through or close to his experience. The one quality in a work of art is a consistent point of view related to the times.

[155]

In addition, interest shifted from the codified way of expressing emotions in Delsartism towards the possibilities of movement as a means of expression. Humphrey sought new approaches to movement with her colleague Charles Weidman (1901–75), who became a long-time collaborator. Humphrey stressed that the choreographer had to constantly search for new movement, not just repeat the movement vocabulary of different styles and techniques. For her, movement observation was a fundamental principle of dance, so that everyday movement was based on the same principles as dance choreography: the anatomical structures of the human body and the expressive power of gestures.[156]

The style developed by Humphrey is based on an alternation of resisting and surrendering to gravity, known as “fall and recovery.”The movement takes place between two extremes, in what Humphrey called “the arc between two deaths.” It reflected Nietzsche’s thinking about the opposing Apollonian (reason, intelligence) and Dionysian (emotion, chaos) forces, both of which as such led to death. The dancer – and human in general – balances between these two opposing extremes. The movement is both physical and psychological, since falling, or going off balance, represents danger and ecstatic abandonment, the opposite of which is returning to balance and being stuck.[157]

For Humphrey, the function of art was to stimulate and move the viewer, which also draws on Nietzsche’s idea that the rituals of Dionysus, as a break from the Apollonian, restrained and orderly everyday life, were needed to maintain the wellbeing of society.[158] For Humphrey, dance was a way of breaking everyday rules through the experience of passion and freedom.

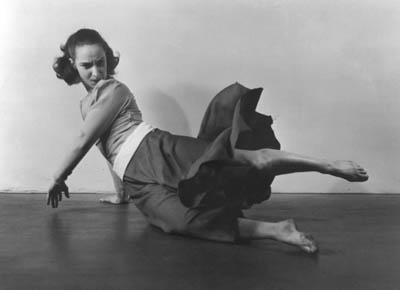

Water Study (1928) is not only Humphrey’s first large-scale group choreography, but also a work in which her philosophy of dance becomes physically visible.[159] The choreography, which proceeds without music and in silence, is based on the dancers’ shared rhythm of breathing, in which each individual is an equally important member of the group. For Humphrey, the conscious use of the rhythm of breathing was central to the construction of the dance, because when breathing, the movement of the lungs spreads throughout the body, becoming the physical engine of all movement. The pelvis is an important starting point for movement, as it builds the connection with the breath and the abdominal muscles. Without this connection, movement of the body starts from the limbs, peripherally, thus Humphrey’s central ideas of a holistic dance “from the inside out” are not realised.[160] Other stylistic features include the constant flow of movement, taking it to extremes and the lyrical nature of the dance.

In Water Study, it is the phrasing of movement, the variation in dynamics and the varied positioning of the group in the space that builds a tension that mediates the flow of water, a continuum of “natural” movement, instead of imitating (mimesis) the movement of water or related imagery. Most of Humphrey’s choreographies convey an idealistic and harmonious worldview, such as Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor (1938), in which the precise movement of the dancers in space is central.