Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker (b. 1960) is a Belgian choreographer, dance artist and founder of the Rosas dance company and The Performing Arts Research and Training Studios (P.A.R.T.S.) school, which opened in Brussels in 1995. She became known in 1982 for her work Fase, which immediately brought a new impetus to European dance theatre and brought ideas about dance from the US Judson Theater into a broader context. De Keersmaeker’s influence has been significant ever since, not least through P.A.R.T.S.

De Keersmaeker’s work is strongly based on the structures of music and the analytical work that arises from them. Spirals, the golden ratio and the Fibonacci sequence are forms, structures and principles that never cease to fascinate her and are included in her choreographic thinking.[1]

The basic elements of choreography include the relationships between space, rhythm and body movements. De Keersmaeker studied music, majoring in flute, but eventually chose dance and graduated from Maurice Béjart’s Mudra School in Brussels in 1980. The following year she went to study at the TISCH School of the Arts in New York. Even before coming to the United States, De Keersmaeker was interested in US minimalist music, particularly the compositions of Steve Reich. Reich’s Violin Phase was thestarting point for De Keersmaekers choreographic practice, which she still continues to work with: “Violin Phase indeed has […] a clear process unfolding through the systems of accumulation, of layering. This music provided me with the tools to develop my own vocabulary and choreographic structure.”[2]

Choreography and Writing (l’écriture)

Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich (1982) was Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s second choreography, which brought her to the attention of first European and then worldwide dance audiences. Fase was created in collaboration with dancer and choreographer Michèle Anne De Mey and premiered at the Beursschouwburg in Brussels. It was later performed at the Avignon Theatre Festival, where it was a huge success and launched De Keersmaeker’s choreographic career.

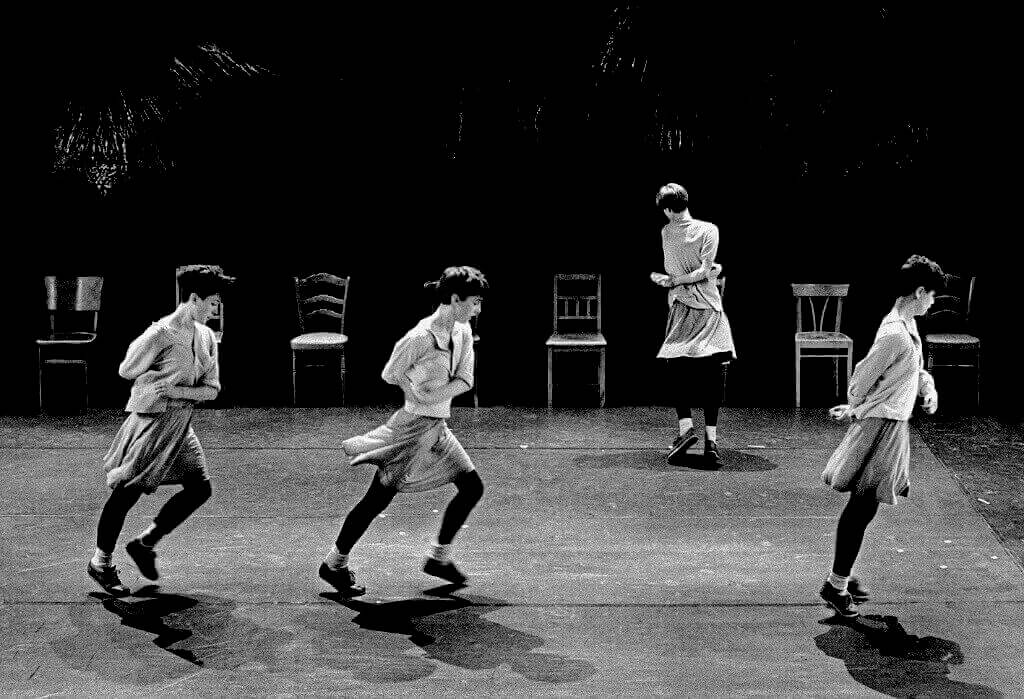

Her next choreography was Rosas danst Rosas (1983), a piece for four dancers that became a cult work. The music was composed by Michèle Anne De Mey’s brother, Thierry De Mey. In Rosas danst Rosas, De Keersmaeker continued the themes she had developed in Fase and applied them to a group of four dancers. The choreography is a combination of everyday gestures and formal, abstract repetitive movements, as well as surprising and unpredictable shifts between stasis and violent, repetitive bursts of movement that often evolve from turning. The controlled, rotating trajectories and rhythmic stops repeated on the floor with the chairs and the vertical application of the movements created a whole new language that was at once personal and conceptual in a lucid, embodied way.

In the post-Judson world, everyday movements had become part of dance vocabulary, and they no longer had the same significance in criticising the canon or creating new meanings or content.[3] Variations on walking, running, arm-waving, jumping, spinning, sitting and lying were also the subject of De Keersmaeker’s movement studies from the beginning. She belongs to the first generation of artists in Europe whose work was situated in the world opened up by the artists of the Judson Dance Theater. This generation of European dance makers had, above all, intellectual space, but also visionary, economic and social support to develop new choreographic thinking and methods and to explore embodied possibilities; the ideals of dance and choreography were no longer rigidly bound to the canons of ballet or modern dance. For De Keersmaeker, simplicity of movement designated avoidance of a virtuosity that would be balletic or analogue to ballet’s ideal body, the limbs extending to the space along a vertical axis.[4]

The variations of everyday movements became sequences and their accumulations, a choreographic tool which found its inspiration in Reich’s music. Activities that were distanced from their functionality, such as sleeping, working, going to the beach, partying and staying up all night, also provided material for movements, from which the dancers worked out extremely reduced movement trajectories.[5] Other essential elements in this choreographic work were repetition, often sudden changes of direction in space, different levels of movement and the circle as the base for both the movement and spatial arrangements. These parameters, combined with a precise, geometric use of space and time, formed the basis on which Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker created her choreographic writing (l’écriture). In her early works, the movement language included everyday movements and quick, rotational and arched moves and turns which changed their quality in a flash to a suspended, short stillness and created variations through accelerations in speed. This dialogue between rotating movement, impact and deceleration requires the dancer to be constantly on their feet and supported from the core in order to maintain lightness and speed of movement, as well as a detailed, kinetic articulation.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s early career started with only female dancers, but gradually male dancers joined the company. The early works contain movement material that can be seen as the feminine vocabulary of the period. It is characterised by a dialogue between softness and surrender, strictness and control, often with girlish costumes and thick-soled shoes. De Keersmaeker has not seen her works as being in touch with social, feminist thought or discourse, and gender narrative has not been an essential element in the works.[6] Gradually, the movement material became more diverse. The rotating movement language of the early period faded into the background, and the material began to include acrobatic jumps, skillful entrances and exits to and from the floor, touches and lifts between dancers.

In Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker’s work, the precise rhythmic trajectories that transform in space like a kaleidoscope require dancers to have an excellent sense of music and spatial awareness. She has collaborated with musicians, composers and orchestras on numerous choreographies.

Relationship to Judson Dance Theater and Contemporary Dance

The spectator can see similarities in De Keersmaeker’s work to that of Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs. American minimalist music, particularly the compositions of Steve Reich, provided the tools through which De Keersmaeker began to develop and realise her choreography.[7] Yvonne Rainer’s ideas on the meaning and quality of danced movement continue to influence De Keersmaeker’s work. She often uses the following quotation from Yvonne Rainer to explain her own heterogeneous material and its meanings:

When I talk about connection and meaning, I’m talking about the emotional load of a particular event and not about what it signifies. Its signification is always very clear. I don’t deal with symbols. I deal with categories of things and they have varying degrees of emotional load.

[8]

In the 1980s, winds of change began to blow through European dance and, in addition to De Keersmaeker, new strong female choreographers with a strongly original and innovative style emerged, such as German Pina Bausch, who had started in the late 1970s, and Meg Stuart from the USA, who had settled in Belgium. Among these, De Keersmaeker represents a style that is clearly based on movement and musical dialogue, in which any theatrical elements are distanced from emotion and self-expression and filtered into a simplified, kinetic form.

In Rosas danst Rosas, one can see references to Pina Bausch’s Café Müller and Kontakthof, where Bausch used chairs as an important part of the choreography. Chairs also played an important role in De Keersmaeker’s early works. Another element linking Bausch and De Keersmaeker is the presence of the dancers on stage throughout the performance as a kind of chorus, supporting their dancing colleagues. According to Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, a dance group is always a collective, not just a group of dancing individuals.[9] The constant presence of the performers throughout the performance is also a strong feature of Pina Bausch’s work, breaking the traditional illusionary practice of dance theatre, where the dancers always disappear into the wings after their number.

In contrast to Bausch’s style, which combines dance and theatre, De Keersmaeker’s work is characterised by a desire for embodied abstraction through movement. Her choreographic work – apart from brief forays into the world of dance theatre and text in the 1990s[10] – is mostly based on a dialogue between music and dance, combining fundamental movement patterns from walking and running with a choreography of space and time.

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker has choreographed more than 60 full-length works, including Bartók / Aantekeningen (1986), Drumming (1998), Rain (2001), Raga for the Rainy Season / A Love Supreme (2005) and The Six Brandenburg Concertos (2018). De Keersmaeker says that when she was working on Fase in New York in 1981, the only thing she listened to apart from the Reich compositions was the Brandenburg Concertos by J.S. Bach. In 2018, De Keersmaeker created The Six Brandenburg Concertos for 16 dancers of the Rosas dance company. She comments her return to Bach: “Bach’s music itself has a unique way of movement and dance, and manages to combine the most abstract with the concrete, the physical and therefore even the transcendental.”

De Keersmaeker herself continues to perform as a dancer, most recently in a choreography based on Bach’s Goldberg Variations from 2020 with pianist Pavel Kolesnikov. Her works have been rarely seen in Finland. Rosas danst Rosas was performed at the Espoo City Theatre as late as in 2019. Previously, Helsinki Festival has presented 3 Abschied (2010), a duet by Jérôme Bel and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, and Bartok / Beethoven / Schönberg Repertory Evening (2006). In 2022, Mystery Sonatas / for Rosa was performed at the recently opened Dance House Helsinki.

In 1996, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker was made a Baroness by King Albert II of Belgium.

The Company Rosas

Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker founded the company Rosas in 1983 during the process of Rosas danst Rosas. Inaddition to De Keersmaeker and Michèle Anne de Mey, the original group included the previously mentioned dancers Adriana Borriello and Fumiyo Ikeda. De Keersmaeker has been the artistic director and choreographer of the company since its inception. The name Rosas was chosen from the title of the piece. Rosas danst Rosas was based on the idea that the dancers dance themselves as themselves, and the principle of repetition, essential to the group’s movement language, was included in the title.[11]

By the end of the 1990s, Rosas had achieved a prominent position on the European dance scene, with other Belgian dance companies and choreographers such as Les Ballets C de la B, Jan Fabre, Needcompany, the aforementioned Meg Stuart and Wim Vandekeybus. Visionaries such as Hugo de Greef, director of the Kaaitheater Festival, helped to establish Rosas from the 1980s onwards.[12] The Belgian state made substantial financial investment in the development of dance and the maintenance of structures since the 1990s, which enabled the Rosas to operate. The company was in permanent rehearsal residency at La Monnaie / De Munt Opera House from 1992 to 2007, and the Kaaitheater provided a home stage for the group’s works. Choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and Rosas have grown over the years into major players whose influence extends across the entire field of Western contemporary dance.

The Performing Arts Research and Training Studios (P.A.R.T.S.)

P.A.R.T.S. was co-founded in 1995 by De Keersmaeker, Theo Van Rompay and Bernard Foccroulle, director of the La Monnaie / De Munt opera house. The idea of the school was born in De Keersmaeker’s mind in the early 1980s, when the Mudra school moved to Switzerland.[13] In 2019, P.A.R.T.S. obtained the right to award master’s degrees. The school was founded with the idea of providing contemporary dance education in Belgium and teaching De Keersmaeker’s movement thinking and repertoire to new generations. Several students and graduates of the school have had the opportunity to work with the Rosas dance company.

Since its inception, the P.A.R.T.S. curriculum has been broad and varied. Its teaching staff has included many important artists and thinkers in contemporary dance. In addition to the works of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, the curriculum includes repertoire by Trisha Brown and William Forsythe and students have worked with the practices of Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargioni, Boris Charmatz, Philip Gemacher, Anne Juren and David Zambrano. In addition, numerous dance theorists and directors, such as Bojana Cvejić, Myriam Van Imschoot, Jeroen Peeters and Jan Ritsema have been lecturing and teaching regularly at the school.

Since its foundation, P.A.R.T.S. has been a major player in European dance education. The school has contributed to the advancement of contemporary dance thinking and to its establishment on the international scene. It can be said that, thanks to its students from many cultures and the prestige it has gained, the school has been able to create a network of partners and collaborations across the contemporary dance scene, often opening up job opportunities for students after graduation. The school has produced a number of dance artists who have become known for their strong artistic vision. These include Alice Chauchat, Nada Gambier, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Mette Ingvartsen, Erna Ómarsdóttir and Salva Sanchis. Rosas and Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker have continued to support and create new working platforms such as Bal Moderne, WorkSpaceBrussels and, most recently, Dancingkids and RondOmDans.

Notes

1 Van Kerkhoven 2002, 33.

2 Cvejic 2012, 25.

3 Cvejic 2012, 14.

4 Cvejic 2012, 14.

5 Cvejic 2012, 14.

6 Cvejic 2012, 15.

7 Cvejic 2012, 9.

8 Cvejić 2012, 13.

9 Cvejic 2012, 15.

10 See, e.g., Stella (1990), https://www.rosas.be/en/productions/380-stella

11 Cvejić & De Keersmaeker 2012, 80.

12 Luyten 2002, 319.

13 Cvejic 2012, 10.

Literature

Cvejić, Bojana. 2012. “Introduction.” In Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker & Bojana Cvejić, eds. A Choreographer’s score: Fase, Rosas danst Rosas, Elena’s Aria, Bartok. Brussels: Rosas & Mercatorfonds, 7–20.

Cvejić, Bojana & De Keersmaeker, Anne Teresa. 2012. “Fase, Four Movements to the Music of Steve Reich.” In Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker & Bojana Cvejić, eds. A Choreographer’s score: Fase, Rosas danst Rosas, Elena’s Aria, Bartok. Brussels: Rosas & Mercatorfonds, 21–76.

Cvejić, Bojana & De Keersmaeker, Anne Teresa. 2012. “Rosas danst Rosas.” In Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker & Bojana Cvejić, eds. A Choreographer’s score: Fase, Rosas danst Rosas, Elena’s Aria, Bartok. Brussels: Rosas & Mercatorfonds, 77–148.

Luyten, Anna. 2002. “Compliance is not my Style.” In Guy Gypens, Sara Jansen & Theo Van Rompay, eds. Rosas: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Tournai & Brussels: La Renaissance du Livre, Rosas, 317–319.

Van Kerkhoven, Marianne. 2002. “Trying to Capture the Structure of Fire: 20 Years of Rosas.” In Guy Gypens, Sara Jansen & Theo Van Rompay, eds. in Rosas: Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Tournai & Brussels: La Renaissance du Livre, Rosas, 31–39.

Van Rompay, Theo. 2006. “Ten Years of Parts.” In Steve de Belder & Theo Van Rompay, eds. P.A.R.T.S.: Documenting Ten Years of Contemporary Dance Education, Brussels: P.A.R.T.S., 14–15.

Contributor

Liisa Pentti

Liisa Pentti (MA, BSc) is a choreographer, dancer and pedagogue and the artistic director of Liisa Pentti +Co. Her work has been performed in Finland, Europe and Russia. Pentti has published numerous articles on dance in various publications since 1996 and has co-edited with Niko Hallikainen the anthology Postmoderni tanssi Suomessa? (2018).