Senegalese dance artist, dance pedagogue and choreographer Germaine Acogny was born in 1944 in Dahomey, now Benin. Known as the Mother of Contemporary African Dance, she has dedicated her life to upholding and modernising African dance. As a passionate dance pedagogue, she has transformed education in contemporary African dance through various endeavours, her artistry and her leadership. During her pedagogical career, she created her esteemed dance technique, Technique Acogny. Amongst many other honours, Acogny received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement from the Venice Biennale in 2021, and the Grand Prix of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 2023.

In this article, I give an insight into the key stages on Acogny’s transformative journey (Mudra Afrique, Technique Acogny, École des Sables), and her artistic works. I also highlight a few influential concepts in her practice (e.g., Pan-Africanism, Négritude) and the political context that made Acogny’s journey possible.

Navigating Africanness and the Francophone dance field

Acogny was raised in colonial Senegal, in line with French cultural values. Her father worked for the French colonial administration before Senegal’s independence in 1960. This paved the way for Acogny to leave Senegal in 1962 to study physical education, harmonic gymnastics and ballet at the École Simon-Siégel in Paris from 1962 to 1968. According to Acogny, her training in Paris was the first springboard for Technique Acogny: “As the only African student, I contemplated the arched feet of my fellows. […] I soon realised that I was incapable of imitating and therefore had to invent my movements which corresponded to my nature.”[1] The training in France strengthened her self-understanding as a Black African dancer, which reinforced Acogny’s thirst for learning how to embody Africanness through dance, following the ideals of Pan-Africanism. Her Pan-African dance aims at uniting and uplifting Africans, both those living on the African continent and those in the African diaspora, by means of African art forms. Acogny’s dance art partakes in Pan-Africanism as it centres the specificity of African dance heritage while developing a universally recognisable modern dance form, Technique Acogny.[2]

Acogny’s dance art centres on a broad range of West African dances that she learned after returning from France. Newly based in Dakar, she kept travelling, for example, to the USA where she was exposed to the work of Black US choreographer and dancer Alvin Ailey. She travelled regularly to Brussels and Paris to work with the French choreographer and innovator of neoclassical ballet, Maurice Béjart.[3] Acogny’s pan-African incentive kept her moving between Senegal and Francophone dance to create “New African Dance”.[4]

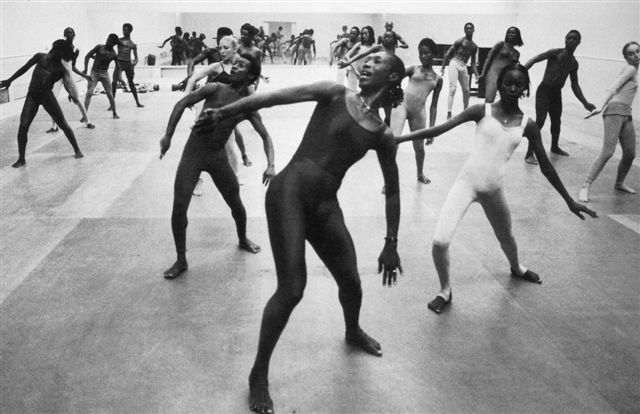

The collaboration with Béjart was intensified when, in 1977, Acogny was appointed as artistic director of Mudra Afrique (Centre Africain de Perfectionnement et de Recherche des Interprètes du Spectacle Mudra Afrique), a dance school supported by UNESCO and the Calouste-Gulbenkian Foundation and launched by the first Senegalese president, Léopold Senghor and Maurice Béjart. As young as 33, Acogny was the head of the most innovative centre for professional dance training in Africa at the time, advocating Pan-Africanism through dance. In the years to come, she refined her vision of pan-African dance into Technique Acogny.

Mudra Afrique: institutionalisation of Pan-African modern dance and its pedagogy

Acogny was the artistic director of Mudra Afrique from 1977 to 1983. To Senghor, she was the logical choice for the position:

I would like to call attention to Madame Acogny’s vocabulary, since it characterises the négritude of her dance. The purpose of African Dance is to ensure that students correctly perform certain dancefigures which Madame Acogny invented, based on black African folk dances.

[5]

Mudra Afrique aimed to train professional dancers capable of fusing African patrimonial dances with ballet and modern dance. Classes were offered in African dances, ballet, modern dance, Technique Acogny and percussion to students from the African continent, alongisde a few from outside Africa. Teachers were recruited from both within Senegal and beyond its borders. Thanks to Acogny’s efforts, the school employed well-known Senegalese drummer Doudou Ndiaye Rose, with whom Acogny had collaborated before. Rose taught drumming in collaboration with his seven sons. As artistic director, Acogny taught, administrated the school and choreographed for students, as Maurice Béjart, who was officially codirecting the school with Acogny, only visited the school once per year.[6]

Through Mudra Afrique Acogny achieved recognition as a dance artist and dance pedagogue both in the African dance scene and internationally. For Acogny, patrimonial African dance addressed “global audiences, and insist[ed] on an Africa that refused to remain in the clutches of the stereotypes”.[7] Mudra Afrique also gave Acogny ideal conditions to fully flesh out her technique. She could realise her ambition to blend African patrimonial dances and Western dance techniques to free “African dance” from the labelling and ethnographic readings common to African national ballet companies.[8]

Technique Acogny: codified dance language

Technique Acogny articulates a decolonial philosophy through the body, foregrounding somatic intelligence, ancestral connection and ecological imagination in movement creation. In Technique Acogny, imagination plays a crucial role in activating the body, which is conceived as a container of the cosmos. To Acogny, the spine is the snake of life. Centring the spine in her technique is an echo of dances in Benin, where the centre of gravity is lower than in Senegalese dances, and generally, the spinal cord is emphasised.[9] Furthermore, Acogny works with the chest as the sun, the bottom as the moon, and the hips as the stars. Imagination plays a key role in the movement creation:

I like the movement of the water lily a lot because it’s in water. I see them dancing, and so I transform them into movement. I give them to the imagination of the dancer. You know the head is the flower and the arms are the leaves that are installed in the water. And the body is the roots. You really become the water lily, or really the frog or the snake.

[10]

According to dance scholar Ananya Chatterjea, referring to natural occurrences is not romanticisation of nature. Rather, Acogny displays “the sensitivity pervading her engagement with the context her work emerges from”.[11] Imagining, sensing and feeling the movement is a crucial energetic way into dancing Technique Acogny. At the same time, the technique’s clear codification, named according to Senegalese flora and fauna, reveals the semiotic incentive of Technique Acogny.

By giving her technique her surname, Acogny resists the prevailing idea of all African dance being one and the same. Africa consists of a myriad of ethnic groups, languages and cultures, including various dance forms. African dance only exists in the plural. Giving her technique a name means it cannot be subsumed under “African Dance”, but instead gestures towards its specificity as one of many techniques.

Regarding existing dance styles, Technique Acogny is sourced from West African patrimonial dances, ballet and modern dance, notably Graham technique. Key physical elements are spinal movements complexified through different rhythmic patterns using undulation, contraction and tremulation. Dance scholar and current head of the École de Sables, Omilade Davis-Smith, identifies isolation of body parts, circular spatial organisation of dancers, multiple rhythms and polycentrism as the particular Africanist aesthetics of the technique.[12]

The technique’s convergence with ballet is more complicated. For instance, in Technique Acogny, the grand plié results in a situation where the dancer, when arriving fully in plié, modulates the pelvis while staying stably on the forefoot. Still recognisable as a grand plié, Acogny challenges the rigidity of the movement’s form. The movement of the pelvis, the heels lifted off the ground, the balancing on the ball of the foot, initiates an intricate trembling that does not allow the fixing of positions. This can be read as a decolonial gesture in dancerly terms. The ballet-sourced shapes of Technique Acogny movements are animated by a body that is always in response to its environment and history. Acogny herself instructs: “When you don’t know where you’re going, look where you’re coming from.”[13]

École des Sables: a transnational meeting point for contemporary African dance

Mudra Afrique closed in 1983 when Senghor retired from public life, which led to a loss of political and ultimately financial support for the school. Acogny followed Béjart to Brussels, where she kept organising and giving workshops in African dance until she moved to Southern France in 1985 where she met Helmut Vogt, her now husband. In the same year, with Vogt she opened Studio-Ballet du 3ème Monde in Toulouse. In 1995, the couple settled in the Senegalese town Toubab Dialaw, where, in 2004, they inaugurated the dance school École de Sable (EDS). EDS is a school, research centre, and meeting point dedicated to the continuous development of the practice and embodied discourse of contemporary African dances. EDS offers “a meeting point of our ancestral dances. It is the foundation for our work, to create new dances for modern times, and especially for Africans to be proud of who they are.”[14]

In EDS, the pedagogical approach Acogny has developed over the years has found a permanent home. Between 2010 and 2023, she has trained teachers in Technique Acogny. Workshop teachers from Africa, the African diaspora and elsewhere visit the school to teach within different professional and non-professional workshop formats and training cycles. Depending on the educational package, students from all over the world may attend classes in Technique Acogny, drumming, contemporary dance, ballet and choreography, combined with field trips to local communities, infrastructure and the natural environment. In addition to two unique dance studios with sand floors and one or more sides open to the vast and rugged scenery, training involves leaving the compound to dance in the natural landscape.

EDS also collaborates with training centres and schools outside the African continent. These types of internationalisation projects are balancing acts. As part of an a capital-driven global education economy, EDS often hosts a fairly large number of paying non-African students. Simultaneously, EDS needs to preserve its original incentive to provide African dancers a professional training context on the African continent, exclusive to Africans. EDS’s dance company, Jant-Bi, which Vogt and Acogny founded in 1994, offers a performative dance space exclusive to African students. Acogny has continuously choreographed for the company, including Faagala (2007) for eight male dancers, a collaboration with Japanese choreographer Kota Yamazaki that addresses the 1994 Rwandan civil war and genocide.

Choreography and artistic collaborations

Acogny is devoted to sharing her knowledge through teaching.[15] Omilade Davis-Smith discusses Acogny’s modern dance as métissage, or crossbreeding, instead of a mélange (or blending) of African and Western dance techniques.[16] Davis-Smith does so with the incentive to show that such African dance traditions fertilise Western dance traditions without being made homogeneous with them. Rather, they create a singular new form of modern dance. Acogny has extensively created work for the stage as a dancer and as a choreographer. In the frame of these dance productions, she unleashes creative forces most often in close collaborations with other artists and cosigns these pieces with them. Collaborations that have resulted in solo works include one with the French theatre director Michael Serre, À un Endroit du Début (eng. At a Place of Beginning, 2015). This solo discusses Acogny’s upbringing, focusing on her relationship with her father, through dance, speech, video and objects. Her 2019 solo Mon Élu Noire (eng. My Black Elect) emerged from a collaboration with French choreographer Olivier Dubois. It is based on a text Dubois wrote for Acogny, but referencing Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Acogny interprets the role of the chosen one, which, three decades earlier, Béjart had promised her but never delivered. Acogny performs a fierce 37-minute non-stop dance, reciting texts by Aimé Césaire and travelling through her own history, deeply marked by colonialism. In common ground[s] (2024), Acogny dances with the former Pina Bausch dancer Malou Airaudo. The autobiographical cochoreographed duet is the first part of a double bill with a new version of Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring danced by an exclusively African cast auditioned through the EDS. Acogny also worked with the Zimbabwean choreographer and dancer nora chipaumire on a collaborative dance film project in 2023. As a dance maker, for Acogny, dialogue and conversation are modes of sharing that prevail in pedagogy and close artistic collaborations alike. Through her collaborations, Acogny keeps inserting herself in differently structured dance and performance histories. Emphasising cross-pollination, she continues nurturing the nonlinear African dance art history, enmeshed in Africans’ ongoing struggle for agency on their own terms.

The nexus of politics and art: Léopold Senghor’s Senegalese Négritude and Germaine Acogny’s modernism

Sengal’s first president, Léopold Senghor, was a poet, politician, cultural scholar and an advocate of Négritude. Developed by Black Francophone artists and intellectuals such as Paulette and Jeanne Nardal, Aimé Césaire, Léon-Gontram Damas and Léopold Senghor, Négritude is a cultural and intellectual movement. By redefining Blackness (Fr. négre), Négritude contests white cultural supremacy. Senghor based his policies for building the new nation Senegal on Négritude where art and culture was regarded as key to reunite African cultures and defy French cultural assimilation. Acogny was well informed about Senghor’s theories and poetry. Her first choreographic work, the solo Femme Nue (Eng. Naked Woman), staged at the Daniel Sorano National Theater in Dakar in 1972, was based on the first line of Senghor’s poem Femme Noire (Eng. Black Woman, 1961). Her commitment to and knowledge of Senghor’s Négritude discourse enabled Acogny to be appointed as Head of the Dance Division at the National Arts Institute in Dakar in 1971.

Acogny’s lifework on dance is indebted to the theories and work of Senghor, and dedicated to the modernisation of African dance. In contrast to other African companies which depicted rural African life, Acogny began to discuss modern, urban topics through her dance art. She addressed issues such as urban livelihood and its challenges in post-independence Senegal, rapid population growth in cities, the resulting in infrastructure strain and housing shortage.

As regards her technique, Acogny deploys the words “modern” and “contemporary” interchangeably.[17] Addressing Technique Acogny more precisely as contemporary dance, art historian Terry Smith defines contemporaneity as: “Place making, world picturing and connectivity [as] the substance of contemporary being.”[18] Layering African and Anglo-European dance traditions designates a placehood of Africanness that maps a decolonial world-building effort. And Technique Acogny’s engagement with both European and US dance forms and African dance highlights a particular connectivity that Ananya Chatterejea calls “generative pollution”12. Through generative pollution, Acogny enables Western modern dance traditions and ballet to feed into African dance heritage without homogenising it, but allowing the emergence of a specific form of contemporary African dance.

Conclusion

Germaine Acogny’s lifelong commitment to dance as a mode of African cultural articulation and pedagogical innovation has positioned her as a key figure in the development of contemporary African dance. Through the codification of Technique Acogny, she has countered reductive representations of African dance. As a result of her deep pedagogical investment, important transnational education centres for African dance have been created, which are excellent examples of how to decolonise dance education. Increasing African cultural agency, Acogny has been driven by perseverance, commitment and the power of imagination. Or to cite Acogny herself: “In any case, I believe one must dream […]. So, dreaming and believing in this dream, and work. Because nothing is earned easily.”[19]

Notes

1 Acogny 1988, 18.

2 See Väätäinen 2023.

3 Klein2019.

4 Sörgel 2020, 19.

5 Acogny 1988, 9.

6 Germaine Acogny + nora chipaumire, YouTube video, posted: 17.9.2021, 1:12:11, 12:51–53, Bajo El Sol, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYO0vcWSN3U, accessed 10.10.25.

7 Chatterjea 2020, 139.

8 Chatterjea 2020, 138–139.

9 RadioFrance 2024, 05:59.

10 “Germaine Acogny reflects on a lifetime in dance | Art Works”, YouTube video, posted: 9.6.2023, 2:54–3:21, ABC Arts, www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtAc8rUpdNU, accessed 10.10.2025. French original: “J’aime becoupt le movement de nénuphar parce que on est dans l’eau. Moi, je les vois danser, donc je les transform en movement. Et je les donne à l’imaginaire au danseur. Vous savez la tete est la fleur et les bras ce sont les feuilles qui s’intallent sur l’eau. Et le corps se sont les racines. On devient vraiment le nénuphar, ou on devient vraiment la grenouille ou l’escargot.”

11 Chatterjea 2020, 143.

12 Davis 2019, 130.

13 Swanson 2019, 53.

14 “Germaine Acogny reflects on a lifetime in dance | Art Works”, YouTube video, posted: 9.6.2023, 7:52, 4:20–33, ABC Arts, 2023. www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtAc8rUpdNU&t=275s, accessed 10.10.2025. French original: “une rencontre de nos danses patrimoinales. C’est la base de notre nouvelle création pour faire la danse des temps modernes, et surtout que les Afriquains soient fiers de ce qu’ils sont.”

15 “Germaine Acogny+Rui Moreira+Suzi Weber”, YouTube video, posted: 5.10.2021, 57:57, 27:19–33, Uni40, www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaFOYn1jIe8, accessed 10.10.2025. French Original: J’ai fais des choréographies mais pas tant que ca parce que j’aime beaucoup enseigner et partager.

16 Davis 2019, 101.

17 Davis 2019, 3.

18 Chatterjea 2020, 138–139.

19 “Germaine Acogny – Grande Dame des zeitgenössischen Tanzes”, YouTube video, posted: 8.2.2017, 2:45, 2:07–2:13, Hellerau, www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFnw1n8v3F8&t=133s, accessed 10.10.2025. French original: En tout cas, croire en ce rêve, et travailler faut rever […] Parce que rien se gagne facilement.

Literature

Acogny, Germaine. 1988. Danse Africaine = Afrikanischer Tanz = African Dance. Frankfurt: Fricke Verlag.

Chatterjea, Ananya. 2020. Heat and Alterity in Contemporary Dance. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davis, Omilade. 2019. “Modernism, Métissage and Embodiment: Germaine Acogny’s Modern African Dance Technique.” PhD diss., Temple University.

Klein, Gabriele. 2019. “Artistic Work as a Practice of Translation on the Global Art Market: The Example of ‘African’ Dancer and Choreographer Germaine Acogny.” Dance Research Journal 51 (1): 8–19. doi.org/10.1017/s0149767719000019.

RadioFrance. 2024. “À un endroit du début.” France Culture. Episode 1/5. Posted: 19.2.2024, 29 mins, 05:59. www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/a-voix-nue/a-un-endroit-du-debut-8236915

Sörgel, Sabine. 2020. Contemporary African Dance Theater: Phenomenology, Whiteness and the Gaze. Camden: Palgrave Macmillan.

Swanson, Amy. 2019. “Codifying African Dance: The Germaine Acogny Technique and Antinomies of Postcolonial Cultural Production.” Critical African Studies 11 (1): 48–62. doi.org/10.1080/21681392.2019.1651663.

Väätäinen, Hanna. 2023. “Afrodiasporic and Pan-African Modern Dance.” In Introduction to Dance Arts – Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Practices, edited by Kirsi Monni, Hanna Järvinen, and Riikka Laakso. Theatre Academy University of the Arts Helsinki: Publication Series of the Theatre Academy 79. URN:ISBN:978-952-353-070-6. disco.teak.fi/tanssin-historia/en/afrodiasporic-and-pan-african-modern-dance/.

YouTube. “Germaine Acogny – Grande Dame des zeitgenössischen Tanzes.” Hellerau. Posted 8 February 2017. www.youtube.com/watch?v=QFnw1n8v3F8

YouTube. “Germaine Acogny + Rui Moreira + Suzi Weber.” Posted 5 October 2021. www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaFOYn1jIe8

YouTube. “Germaine Acogny + nora chipaumire.” Posted 17 September 2021. www.youtube.com/watch?v=JYO0vcWSN3.

YouTube. “Germaine Acogny reflects on a lifetime in dance | Art Works.” ABC Arts. Posted 9 June 2023. www.youtube.com/watch?v=DtAc8rUpdNU

Contributor

Jana Unmüßig

Jana Unmüßig is an artist and researcher with a background in choreography, dance, and theater studies. Since 2019, she has collaborated with Berlin-based choreographer and performer Miriam Jakob in their joint artistic research project Breathing With which resulted in publications, workshops, and performative assemblages. Jana holds a doctorate (2018) from the Theater Academy of Uniarts Helsinki where she works as a lecturer in choreography.