Spanish dancer and choreographer La Ribot (Maria Ribot, b. 1962) constructs a wide range of choreographic landscapes at the interface of contemporary dance, visual and performance art. La Ribot trained internationally in the 1970s and 80s in ballet, modern and contemporary dance techniques and worked as a dancer and choreographer in Madrid in the late 1980s. In the early 1990s, La Ribot’s choreographies began in many ways to dismantle both dance conventions and social norms, often in relation to the (female) body. La Ribot’s works explore the body from a variety of angles, observing and questioning the realities and discourses that emerge from its existence, function or movement. Like her contemporaries Jérôme Bel and Xavier Le Roy, in her work La Ribot proposes a multiartistic approach where elements of performance, minimalism and conceptualism are present.[1] (see article The Tricky Category of “Conceptual Dance”)

Miniatures and Their Series: Panoramix (1993–2003)

La Ribot’s long-running project Piezas distinguidas (“Distinguished pieces”) began in the early 1990s, when the choreographer started to create a kind of choreographic miniatures, short pieces lasting from 30 seconds to seven minutes. These miniatures were presented in series, the most famous of which is Panoramix (1993–2003). The event brought together all the miniatures created over the last ten years, and carefully organised them spatially into a precise choreography.

The pieces approach choreography from many angles. In the first miniature she created, Muriéndose la sirena (“The dying mermaid,” 1993), La Ribot lies on her side on a cardboard-covered floor, her feet under a white cloth and a blond wig covering her face. The soundscape consists of the sounds of a garbage truck, to which La Ribot’s body sometimes convulses, sometimes pulsates and vibrates almost imperceptibly. The piece combines installation and micro-choreography. The miniature works often simultaneously inhabit many forms and realities – the performer’s body may be a person, an object or a machine[2] – while different materials (skin-fabric-plastic or naked body-nylon wig) form sensory-stimulating compositions.

Humour is a key element in the miniatures. Like the works of Erik Satie, Piero Manzon, Buster Keaton and Joan Brossa, La Ribot’s pieces have a certain modesty, while humour breaks down hierarchies between “high” and “low” art or emphasises the relativity of things.[3] José A. Sánchez describes humour as a kind of engine:

If we can speak about humour in relation to the Piezas distinguidas, it is because they have been conceived of and constructed from a vital and creative attitude that rejects being straight, oppressive, fixed and tedious, and prefers instead to be ludic, subtle, free-flowing and ironic.

[4]

Besides the miniatures this vitality extends to all of La Ribot’s artistic work, in which humour carries criticism, while pleasure and beauty combine with wounding irony, as in Gustavia (2008), a physical exploration of the humour of the burlesque tradition by La Ribot and French choreographer Mathilde Monnier. In this work, the compulsive repetition or tortuous slowness of a movement or action transforms the atmosphere of fun into one of tension.[5]

Humour also softens the treatment of violence against the body, as in miniature number 28, Outsized Baggage (2000), in which La Ribot wraps a rope around herself, from head to ankles, so that the rope draws lines on her body over the breasts, waist and hips. The (female) body is at once fragmented by drawing the proportions of an ideal female figure, a tightly bound parcel of mail and a reference to bondage art. Finally, La Ribot puts on a paper ribbon resembling a beauty pageant contestant’s or marshal’s sash, or a long luggage tag stating the destination, e.g. Heathrow, London. La Ribot’s work is influenced by the visual poetry of Joan Brossa, who combined two different realities in a conceptual confrontation, a kind of neo-surrealism. Brossa’s way of transforming the poem into an object is reflected in La Ribot’s way of embodying the object.[6] Moreover, each miniature choreography has an owner – the pieces are sold as art objects and the owner’s name is always visible when the piece is performed – which raises the question of the ownership of art or the capturing and selling of the ephemeral nature of dance as an object.

At first, the miniatures were presented in frontal stages; later the venues changed to gallery spaces and the works became multidimensional spatial entities.[7] Panoramix (1993–2003) consists of 34 successive miniatures and premiered at the Tate Modern in London in 2003. Choreographed by La Ribot, the spatial and temporal sequence, a kind of route inside a transforming choreographic installation, lasts for about 3.5 hours. At the start of this “long duration performance,”[8] objects and clothes are spread out on the gallery floor or carelessly taped with masking tape to the walls as a chaotic exhibition. As La Ribot uses each object in turn, the institutional dignity of the art objects that characterises the galleries disappears while the singularity, meaning and memory of the objects become central.[9] Each object activates La Ribot’s naked body, constructing the precise action of each miniature: her skin is like a canvas on which different clothes and objects are hung in turn. In her performance, La Ribot tries to step out of the space of representation, towards a body that is hesitant, trembling and lived even while still.[10]

The gallery as a dance venue de-hierarchises the theatrical situation and creates an opportunity for a more equal use of space. The construction of illusion through lighting is limited, as is the sound design, which blends with the sounds produced by the bodies of the audience. The audience moves around the space without assigned seating, and the soft cardboard-covered gallery floor invites the audience to sit – and to put their bags down next to the objects used in the performance. La Ribot transforms the gallery space, an institution of visual art, into an unstable and undefined landscape.[11] Panoramix proposes a dialogue with visual art and explores the relationship between dance and installation and sculpture in a way that André Lepecki likens to Trisha Brown’s works that combine drawing and movement.[12] (see Trisha Brown: Brown drew throughout her artistic career…)

The perspectives of viewing the work are undefined, as the audience follows La Ribot around the space, positioning themselves in different compositions around her to watch the next part of the work. The space is shared through empathy. The performer – a naked woman – responds to the gaze of the audience, who cannot hide in a darkened theatre auditorium, out of sight of the performer or the other spectators.[13] The bodies of the audience are also exposed, reacting by laughing, gesturing or turning away. The transforming presence of the audience is part of the work. Panoramix becomes the ultimate event of presence, where nothing can be hidden, while looking is replaced by being together: the work is about “to be with La Ribot”.[14]

Laughter as Technique, Action and Critique

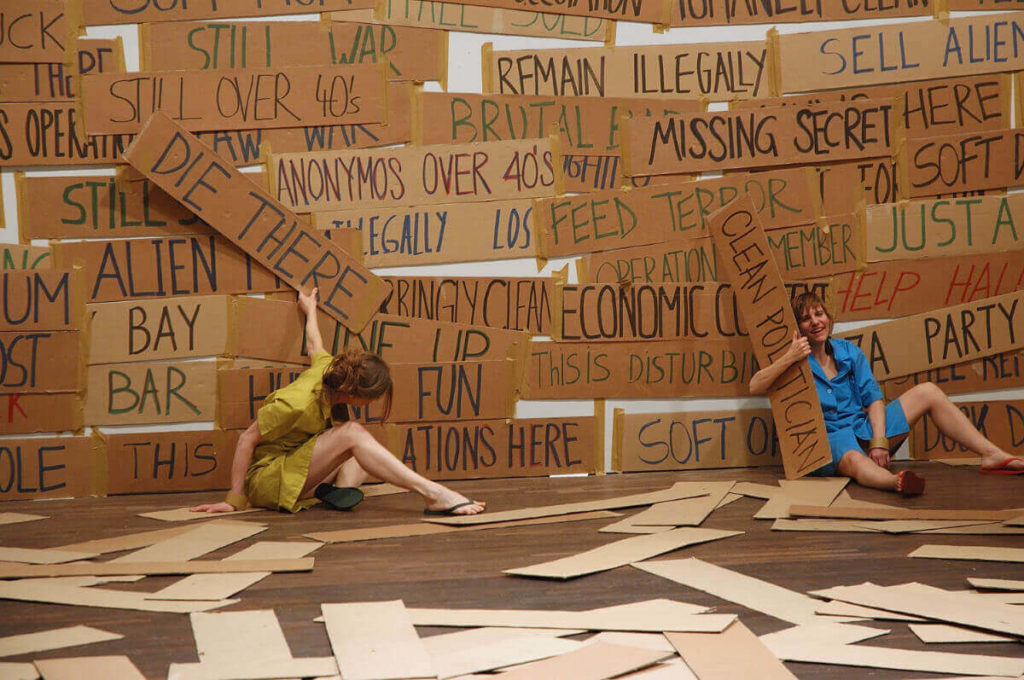

Laughing Hole (2006) also stretches the notion of time and space. The work is based on a simple task structure that is repeated by three performers. A strip of cardboard is picked up from the floor of the space, its text is raised for the audience to see, the cardboard is carried like a sign and finally it is attached to the wall with masking tape. All this is done while the performers laugh nonstop throughout the six-hour piece, using the laughter technique developed by La Ribot.[15]

As the work unfolds, the laughter changes at moments from a light chuckle to a raucous bellow or a harsh, weeping-like howl. At times, it is seen as a physically demanding performance, while at other times the connection between performer and spectator makes laughter easy and contagious. The texts that emerge when the cardboard is turned also shape the laughter, with TODAVÍA PERDIDO (“still missing”), ESPECTADOR VENDIDO (“sold spectator”), GUANTÁNAMO BUSH, POLÍTICO LIMPIO (“clean politician”), NO VIOLAR (“must not be violated/raped”) offering different meanings to the situation. Words repeated in the signs, such as “clean,” “clean up,” “hole,” “laugh” and “sell,” are mixed with words referring to politics, especially the United States and Guantánamo.[16] They are repeated and combined with a random logic to form a set of political slogans, poems or orders. The performers are dressed in colourful house dresses and plastic toe sandals, evoking associations with cleaning or the working class. Cleaning and cleansing are seen not only as a concrete action but also as a ritual of cleansing, and cleaning can be read as cleansing society of corruption.

The work forms a dynamic choreography of signs and meanings, constructed not only by action and words but also by sound: the nonstop laughter is shaped by real-time sound design, which occasionally rises up into a storm or breaks up into separate small streams of laughter cohabiting the space. Even the movement – the performance of a task – sometimes clumps into messy stumbling and scrambling, subsides into functional performance or brightens into playful merriment. The audience’s freedom to move out of the space and back in again shifts the responsibility for participating in the six-hour ritual to the spectator. Laughing Hole’slong-lasting performance challenges the viewer’s perceptive abilities: the work stretches the perception of time and the density of action. Furthermore, the careless and illogical attachment of strips of cardboard to walls, windows or radiators calls into question the structures created by the architecture of the space.[17]

Laughing Hole is an installation of laughing bodies in which the viewer becomes aware of the demanding nature of performing laughter and the difficulty of sustaining and renewing the state of laughter throughout the six-hour duration of the work. At the same time, laughter acts as a critical instrument that disrupts bodily communication, freeing the performers from the norms of social control over the body. Laughter disrupts the order of contemporary society and interrupts its steady rhythm. Laughing Hole is a place of strong political disobedience, as La Ribot makes a “hole” in reality where social rules are changed and anything is possible.[18]

40 Espontáneos (2004) uses laughter both as a tool of physicality and to build a connection between a group of nonprofessional performers. Working with amateurs creates an alternative to the way professional performers manage the performance situation: the work presents not only a wide range of ways of moving and being, but also very heterogeneous bodies. In 40 Espontáneos, the movement materials the performers work with and the piece’s composition initially seem random. However, the repetition of the material gradually shows that the “shapelessness” is a construction reflecting a different internal logic and a different way of understanding.[19] The elevation of the faceless or anonymous actor as performer is also central in FILM NOIR (2014–2017), for which La Ribot observed the embodiment of background actors in Franco-era Spanish films and filmed working bodies as dance.[20] Happy Island (2018) is a collaboration with Dançando com a Diferença, a group working on inclusive dance. The piece explores desire and sexuality through different physical characteristics, for example in a body whose way of being is an ever-present vibration.[21] (see Ableism in Dance and Disabled Dancers.)

La Ribot can be counted among the group of European dance artists who united in a critical view of the 1980s boom brought about by the consolidation of production structures and financing in contemporary dance. The institutionalisation of dance and the standardisation of both dancer education and the dancing body were at the heart of the critique of the political and economic causes behind the spectacularisation of contemporary dance. La Ribot’s works question how consumable dance is by stretching space and time beyond the limits of pleasure, making the spectators visible and making them co-responsible for the performance. In many ways, her work expands the notion of the performer’s physicality and skills and, more generally, of what dance is – or could be – by exploring very different ways of being, operating and moving as dance.

Notes

1 Heathfield 2004, 23.

2 Sánchez 2004, 41.

3 Sánchez 2004, 39.

4 Sánchez 2004, 39.

5 Burt 2017, 147–150.

6 Sánchez 2004, 40.

7 13 Piezas distinguidas (1993–1994), Más distinguidas (1997) and Still Distinguished (2000) were all set in theatre spaces. Panoramix has since been shown at venues such as the Pompidou Centre in Paris and the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

8 The term was used in the press release of the work. Lepecki 2006, 65.

9 Heathfield 2004, 22.

10 Lepecki 2006, 82.

11 Lepecki 2006, 76–78.

12 Lepecki 2006, 65–86.

13 Heathfield 2004, 22.

14 Heathfield 2004, 22.

15 Burt 2017, 114. La Ribot was one of the performers in the early stages of the work; later she became an observer. The observations in this text are based on a version of the performance at the Mercat de les Flors in Barcelona on 27 April 2019, with Tamara Alegre, Ruth Childs and Olivia Csiky Trnka.

16 The work was originally built in 2006 as a protest against George Bush and the Guantánamo Bay prison camp.

17 Burt 2017, 111.

18 Burt 2017, 113–115.

19 Burt 2017, 110.

20 https://www.laribot.com/work/36

21 https://www.laribot.com/work/60

22 Burt 2017, esp. 3–4. Silva 2017, 182. Both authors refer to Ginot, Isabelle & Michel, Marcelle. 2002. La danse au XXe siècle. Paris: Larousse. The growth of contemporary dance field in the 1980s was linked to the consolidation of the production structures and financing of dance. For example, recognisability and consumption of choreographic style were subjected to critical scrutiny. In addition to Jérôme Bel and Xavier Le Roy, Boris Charmatz and Christophe Wavelet are often counted among these contemporary dance choreographers.

Literature

Burt, Ramsay. 2017. Ungoverning Dance. Contemporary European Theatre Dance and the Commons. New York: Oxford University Press.

Heathfield, Adrian. 2004. “In Memory of Little Things.” In Claire Rousier, ed. La Ribot. Volume II. Pantin & Gent: Centre national de la danse & Luc Derycke & Co/Merz, 21–27.

Lepecki, André. 2006. Exhausting Dance. Performance and the Politics of Movement. New York and London: Routledge.

Lista, Marcella. “Biography.” https://www.laribot.com/biography Accessed 7.7.2022.

Sánchez, José A. 2004. “Distinction and Humour.” In Claire Rousier, ed. La Ribot. Volume II. Pantin & Gent: Centre national de la danse & Luc Derycke & Co/Merz, 39–49.

Silva, João Cerqueira da. 2017. Reflections on Improvisation, Choreography and Risk-Taking in Advanced Capitalism. Kinesis. Helsinki: University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy.

Contributor

Riikka Laakso

Riikka Laakso works in the field of dance as a writer, lecturer and dramaturg. She holds a PhD in performing arts from the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (2016) and teaches theatre analysis and dance history at the Institut del Teatre de Barcelona. Laakso has collaborated with Zodiak – Centre for New Dance, the Theatre Academy, Helsinki and choreographer Sanna Kekäläinen, and is responsible for the dramaturgy of works by choreographer Marina Mascarelli.