I am not so much interested in how people move but in what moves them.

Pina Bausch

Pina Bausch is an iconic figure on the European dance scene. Her groundbreaking work with the dancers of the Tanztheater Wuppertal gave new meaning to the German concept of Tanztheater, which had evolved from Ausdruckstanz in Germany and Austria of the1920s. Its famous developers were Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss and Rudolf Laban. Under Bausch’s leadership, the Tanztheater Wuppertal became increasingly well-known from the late 1970s onwards, until it had a worldwide audience.

Bausch’s experimental search for her own form of artistic language, challenging the dialogue between dance and theatre and developing new dramaturgical and performative forms were at the heart of her artistry, although almost without exception, her pieces (Stücke) were performed on large, traditional stages for large audiences. From the beginning, Bausch’s art was defined by questions about the relationships and possibilities between theatrical space and performing and between audience and performers, for which everyday movements and everyday activities and habits, traditional dance techniques, speech and song provided the formal tools.

Bausch’s importance for art dance can be considered very special, since humanity and the difficulty of being human in an unjust and cruel world become the main themes in her work. The human being with their fears, pettiness, joys and sorrows, the tragedy of humanity and yet, in the midst of it all, the longing for intimacy and laughter were essential to Bausch’s work.

Bausch’s dance theatre has been compared to the theatre of Beckett and Ionesco – “Their literature is in no way didactic: they neither preach or teach”[1] – in which humankind’s innate capacity for stupidity and incomprehension is one of the central themes. Bausch’s work almost always included absurd situations and humour, which could turn into violence at lightning speed and then slide into slapstick. Levels of humour, cruelty and tenderness intersected in the pieces, always leaving interpretation to the viewer – no definitive answer to questions was given. The alternation of comedy and tragedy made the violence in the pieces tolerable.[2]

Interpreter of Her Era

Pina Bausch was born on 27 July 1940 in Solingen, Germany. It was the first year of the Second World War, and Bausch’s youth was set in West Germany in the aftermath of the war that had then claimed the most lives in the world. Bausch belonged to a generation of artists whose work expressed the surrounding society and its many tensions and contradictions, as well as an awareness of the recent past with its many unresolved questions.

Germany’s existence, history and values had been buried with the collapse of Nazism. After the end of the war in 1945, Germans began the frenetic construction of a new society, which included widely divergent views of the lost war and its causes, as well as divergent relations with the Holocaust, which largely defined the country’s atmosphere and cultural life. There was a desire to move forward and create a new welfare state, to forget as soon as possible the horrors of the past war and to keep silent about its experiences.

The pervasiveness of Bausch’s art and its relationship to the world can be understood through her personal history. Her identity has always been defined by dance. Pina Bausch began dancing ballet as a child and in 1955 was awarded a scholarship to the Folkwangschule in Essen, which even then was known for its interdisciplinary approach to the arts. Besides dance, the school offered the opportunity to study visual arts, photography, graphic arts, music and mime. Students were encouraged to cooperate with other departments.[3] These influences provided Bausch with the opportunity to develop in a multi-artistic atmosphere and laid the foundations for her future work as a choreographer. In her own words, the most important teacher was Kurt Jooss, who can be considered a pioneer of European modern dance. Jooss was one of the founders of the Folkwangschule and created its dance group. Bausch later said: “What good fortune to have met him at such a decisive age.”[4]

After completing her studies at the Folkwangschule, Bausch was awarded a German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) scholarship to study at the Juilliard School of Music in New York. This period also proved to be decisive for her future. Her studies included the Graham technique, taught by Mary Hinkson, a dancer in Martha Graham’s company. Other teachers included José Limon, Anthony Tudor and Margaret Craske.[5] Bausch’s experience was that in New York, people from different cultures and backgrounds, nationalities, fashions and aspirations could coexist. This multiculturalism was something she later appreciated in her dance company.[6]

After her studies, choreographer Anthony Tudor, artistic director of the Metropolitan Opera, took Bausch into his company, where Bausch worked as a dancer until 1962, when she was invited to join the Folkwang Ballet under Kurt Jooss. The decision to return to Essen was not an easy one, but gradually Bausch was given the opportunity to try her hand at choreographing for the group. Studying and working in New York provided an important platform for Bausch’s developing art.[7]

In 1969 she became director of the Folkwang Tanzstudio, and in 1973 she was appointed director of the Wuppertal Bühnen Ballet. The ballet company soon became known as the Tanztheater Wuppertal. In 1983 she was also appointed head of the dance department at the Folkwang University.[8]

Pina Bausch developed her choreographic thinking throughout her life. Her work with the Tanztheater Wuppertal as its choreographer and artistic director could be divided roughly into three distinct phases:

- 1973–1978. Experiments with the relationship between dance, music, drama and text. During this period, Bausch began to develop a technique based on a list of questions to ask dancers, using keywords (Stichworte).

- 1978–1986. The “vintage” pieces of dance theatre were created and became world famous. These include Café Müller, Kontakthof, 1980 – Ein Stück von Pina Bausch, Walzer and Nelken.

- 1986–2009. Institutional collaborations and co-productions in different countries.

I will briefly discuss each period, highlighting the most important elements.

Early Experiments

When writing about Pina Bausch, it is important to see how her pieces are situated in the history of the performing arts and social change. Bausch draws inspiration not only from the tradition and development of dance, but also from the questions that theatre itself posed in the 20th century, in particular the insights of Antonin Artaud, Berthold Brecht and Jerzy Grotowski on the relationship between performer and audience, and the political and social significance of theatre. These insights included new radical proposals for unveiling the stage and the illusion it creates, the dialogue between fact and fiction, and the activation of the spectator from passive recipient to provocative and sympathetic participant who is questioning the reality of the performing arts. Audience and performers share the same space and reality, which is constantly changing. In Bausch’s pieces, the dancer-performers represent themselves and all of us, bringing to light something essential about the human condition.

Bausch’s work reveals her awareness and consciousness of history and the zeitgeist. As a choreographer, she and the dancers created an entirely original world, where the rules of carnival apply, and no right answers are to be expected, including the beginning or end of the performance.[9] Many pieces, including early ones, have survived Bausch’s sudden and unexpected death in 2009. They are constantly performed as part of her company’s repertoire, circulate in dance artists’ conversations as internal references, and serve as source material for academic dance research.

In particular, Bausch’s interpretation of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (Das Frühlingsopfer)has achieved almost canonical status. Along with Nijinsky’s original version from 1913, Bausch’s interpretation of The Rite of Spring is one of the best-known among numerous interpretations of the famous composition. Premiered in 1975, it was the last of Bausch’s pieces to be performed solely by means of traditional dance and music. One reason why her interpretation was so popular was that Bausch questioned the earlier narratives of The Rite of Spring and brought into focus the violence that society inflicts on women. Bausch’s movement language is brutal and incessant, and almost inhuman in its unrelenting repetition.[10]

The following year, she made a musical performance of a play by Brecht and Weill, entitled Die Sieben Todssünden / Fürchtet Euch nicht (The Seven Deadly Sins / Do Not be Afraid). This was very negatively received by critics and the public. In addition, a serious crisis arose between Bausch and the dancers. The dancers did not trust Bausch as a choreographer, and Bausch said that for the first time in her life she was afraid of the dancers, who hated the work. Most of the dancers in the company quit, and Bausch vowed never to enter the Wuppertal theatre again.[11] The Seven Deadly Sins was faithfully based on the original libretto, and this was the last time Bausch relied on the logic and form of traditional storytelling.

This first period includes Bluebeard (1977), based on Bela Bartok’s music and depicting the women’s subordinate relationship to men. Bausch first used a list of questions as the starting point for the choreography, which was based on Act I Scene 6 in Shakepeare’s Macbeth, in a 1978 piececalled Er nimmt sie an der Hand und führt sie in das Schloss, die anderen folgen... (He Takes Her by The Hand and Leads Her Into the Castle, The Others Follow). In this piece, only fragments of the text remained and the dancers’ movement language was strongly based on an exploration and observation of the differences between everyday activities and performativity of the traditional performer. Art scholar Lucy Weir describes the piece as “a disjointed, chaotic spectacle”[12] whose only constant motif is water. In one performance of the piece, the audience protested so strongly that dancer Jo Ann Endicott shouted at them from the stage mid-performance, “If you don’t want to watch, go home and let us work!”[13]

Developing Aesthetics and Methods

From then on, Bausch’s work began to show a collage-like choreography as a result of a process based on questions posed to the dancers, which combined material produced by the dancers themselves, dance movements and speech as equal elements. Bausch posed questions by working with a list of keywords (Stichworte). With Bausch, the dancers experimented and found different ways to answer those questions.[14] The process was a slow one, with rehearsals lasting three to four months. The dancers worked on their own responses through movement, speech and song, and gradually they developed into precisely articulated, rhythmical scenes based on repetition and various movement or verbal gestures, from which Bausch composed the performance. A very particular choreographic feature was lines of dancers one behind the other, swaying to the music and the lines that faced the audience, in which the personalities of the group’s performers were allowed to shine through simple repetitive action.

Collaboration with the dramaturg was essential during the long rehearsal processes, as only a small part of the material produced by the dancers ended up in the final piece. Dramaturg Raimund Hoghe was Pina Bausch’s dramaturgical collaborator from 1979 to 1990. Here is an extract from his notes on the piece, showing the chains of association between keywords:

Seven ways to say “I’m doing great”: I could fly, I could fetch all the stars from heaven for you, I can do everything, I’m not afraid, I could burst with joy, I could hug everyone, I feel so light / What is one most afraid of: being very ill and in terrible pain, losing someone that I’m very fond of, that I’ve missed something and someone else suffers because of it, being able to help someone and not doing it, noticing that I’ve not lived, etc.

[15]

Slowly refining and working with the material, Bausch gradually progressed from evocations and scenes evoking questions to a choreography whose form was dramaturgically fragmentary. According to Bausch, her working method was intuitive and open; she had no idea beforehand in which direction the process would take her.[16] Bausch said that in her work, parallels between different ways of doing things and contrasts of emotions were important:

Hope belongs to worry, longing for the lost person belongs to loss. I would like people not to give up hope, and I want to embolden them. I get bored if I can’t feel anything […] Cheerfulness means nothing. In each piece there is always the opposite, just as in life. […] If there was nothing to laugh about I don’t know how I could go on.

[17]

The Golden Pieces and the Postdramatic Stage

The experimental Macbeth project in 1978 was followed the same year by Café Müller and Kontakhof, through which Pina Bausch and Tanztheater Wuppertal soon became known to audiences outside Wuppertal and internationally. Café Müller and Kontakthof revealed Bausch’s mature and distinctive artistic vision as a choreographer. This was based on founding the trust, a common language and a way of working with the dancers.

Other vintage pieces were created in this period: 1980 – Ein Stück von Pina Bausch, Waltz and Nelken (Carnations) in 1982. The pieces also featured the Verfremdungseffekt, or alienation, a performance tool developed by Brecht to prevent the audience from identifying with the role played by the actor. It can be seen that Bausch used movement and verbal repetition as one means of achieving alienation.[18] Bausch defended her excessive use of repetition by saying that repressed childhood memories could only be recovered by listening carefully to one’s own socially conditioned body. We have to return to it again and again, and perhaps the saddest thing about our own obsessions is that they often seem so hilarious.[19]

Bausch’s work is a realisation of Hans-Thies Lehmann’s idea of postdramatic theatre, that “the new theatre reinforces the old insight that there is an eternal contradiction between text and stage.”[20] Brecht’s idea of the absence of the “fourth wall” of the stage also became apparent in Bausch’s work. The dancers made direct contact with the audience, asking rhetorical questions, shouting a direct cry and in the next moment singing or moving among the audience, for example, offering tea. Art researcher Lucy Weir also suggests that Bausch’s way of not telling a story can be likened to the collage technique created by film director Sergei Eisenstein for film. Bausch, like Eisenstein, did not tell a story but told things and allowed the viewer to piece them together.[21]

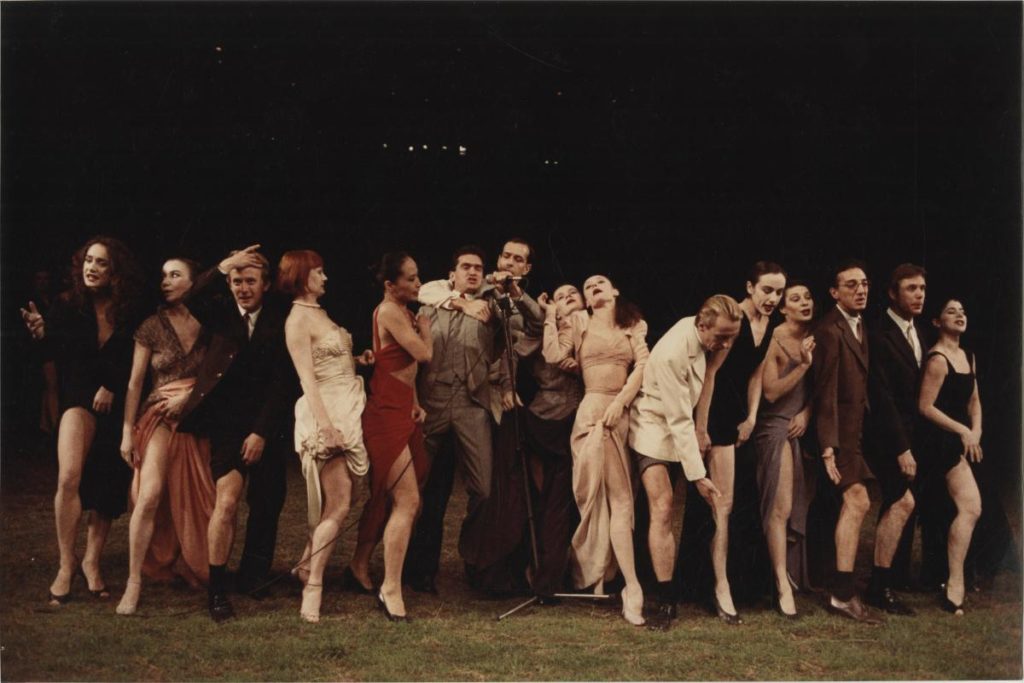

All Tanztheater Wuppertal performances were made for large stages and audiences. Bausch and her company broke down the conventions of dance that had existed up to that point, concerning the performer and the relationship between spectator and audience in traditional theatre and opera houses. Initially, the audience consisted of spectators used to seeing traditional dance, and in their world the performances had until then remained safely behind the fourth wall of the stage. Wuppertal Tanztheater’s performances sucked the audience into the narratively free, dreamlike worlds created by Bausch and the dancers, where the imagination, energy and surrender of the performers crossed the boundary between audience and performance time and time again. Pina Bausch’s work can be viewed through many conceptual frameworks, but Bausch’s choreographic talent lay in her ability to create unprecedented dance art, aware of theatre historical references and able to fuse performing arts traditions and impressions of moving through time into a new form of performance.

From the beginning, set design was an integral part of Bausch’s work and aesthetic. It was an important functional environment for the dancers, a poetic, physical and material place to dance and perform. Often the decor was an organic element – earth, water, plants, flowers – or a single dominant element, such as the chairs in Cafe Müller or the peat soil in The Rite of Spring. In Cafe Müller, the dancers collide with the chairs, and in The Rite of Spring, the peat mound clutters the stage and gets in the dancers’ way as the sacrificial ritual progresses. The aesthetics of alienation worked here too, in that the staging did not seek to create an illusion of another world or place, but to maintain an awareness of the stage, the performance and the construct built there. The set could be a stage-sized grass carpet, on which a harmonium, a stuffed deer and stage lighting stands coexist, as in 1980 – Ein Stück von Pina Bausch. Bausch also used live animals as performers, as in Nelken, in which two German shepherds patrol the stage on several occasions.[22] Bausch’s most important and closest collaborator at first was her partner, set and costume designer Rolf Borzik. After his death, since 1980 – Ein Stück von Pina Bausch, theset designerwas Peter Pabst, according to whom Bausch made little comment on his suggestions, but could at most ask the question: “And what else can it do?”[23]

Premiered in 1984, the harsh and grim Auf dem Gebirge hat man ein Geschrei gehört (On the Mountain a Cry Was Heard), takes its name from the text of J.S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion. In it, Bausch bypasses the technique of alienation she had used in earlier pieces and challenges and provokes the audience by introducing violent scenes in which the boundary between spectator and performer becomes increasingly fragile. There is no trace of the hope of earlier pieces in terms of human relationships, but the performance is purely dark and oppressive.[24]

International Collaborations

In 1986, the era of collaboration began in Bausch’s work. It consisted of 15 performances, produced collaboratively with cultural centres in different countries. They were made possible thanks to the generous international support of institutional cultural actors.[25] The first internationally produced piece was Viktor, co-produced with the Teatro Argentina in Rome in 1986.[26] Other pieces from this period include Palermo, Palermo (1989), Der Fensterputzer (The Window Washer, 1997), Água (2001) and Bamboo Blues (2007).

The group was in residence for three to four weeks, and then returned to Wuppertal to work on the piece. The pieces did not seek to represent the place where they originated, but continued the way of working based on Bausch’s questions. Working in different places allowed for new observations and insights in relation to different cultures and their practices.[27]

The form of the pieces also gradually moved away from theatrical means, such as Brechtian alienation effect, and the pieces began to contain more purely dance elements and elements associated with traditional choreography. The emotional scale of the work became more optimistic, with new themes of pleasure, tenderness and understanding dialogue between people.[28] The pieces also became more visual, emphasising traditional, classical beauty and lightness, while themes that had previously been present, such as the complexity of the human mind, anxiety and violence, were relegated to the background, although they still formed the content of the whole. Comic scenes also remained elements of the work.

The dance group became even more international. The work continued to be based on asking questions and on the basis of the responses, producing material. Movement materials, gestures and actions from the dancers’ different cultural backgrounds began to shape the content of the pieces in a new direction. Pina Bausch’s dance roots were twofold: both in the tradition of ballet and German Ausdruckstanz, and in American modern dance, particularly through Martha Graham. Perhaps this contributed to the fact that dance, particularly modern dance and contemporary ballet with its derivatives, featured strongly in the content of the pieces in Bausch’s late period. Paradoxically, these European and US traditions provided a common denominator for a group of dancers with very different histories and cultural experiences and allowed for shared experiences.

Pina Bausch’s last choreography was… como el musguito en la piedra, ay sí, sí, sí… (Like Moss on the Stone) in collaboration with the Festival Internacional de Teatro Santiago a Mil and the Goethe Institute. It premiered on 13 July 2009. Ten days later, Pina Bausch died from cancer, which she had been diagnosed with unexpectedly. The final piece contains no hints or signs of death and is, according to Martha Meyer, “full of celebration and life.”[29]

It is difficult to categorise Pina Bausch’s work into a specific genre.[30] Bausch was known for her terseness and her reluctance to explain or reveal much of the background to her work. Although it would be easy to classify her as a radical, dance-changing, visionary choreographer, Bausch, in her own words, never wanted to provoke the public, but only tried to speak about us humans.[31]

Memory and remembering,[32] fear, longing, doubt, the search for happiness, the ultimate cruelty of life and the contrast between the innocence of childhood and the ruthless world of adults were themes that Bausch explored in most of her pieces.[33] She analysed the world of human relationships with analytical rigour, intelligent irony and sensitive humour, exploring the inability of people to communicate, exploitation, humiliation and interdependence.[34] The resulting scenes formed a choreographic whole that reflected something essential about the tragic experience of being human, but which the audience could read and experience in many different ways.

After Bausch’s death, the Tanztheater Wuppertal continued to operate and continues to perform both Bausch’s choreographies and more recent pieces created for them. In 2022, French choreographer Boris Charmatz took over as artistic director.

Notes

1 Weir 2018, 84.

2 Meyer 2017, 66.

3 Meyer 2017, 13.

4 Meyer 2017, 14.

5 Weir 2018, 9.

6 Meyer 2017, 20.

7 Weir 2018, 32.

8 Meyer 2017, 218.

9 Weir 2018, 73.

10 Weir 2018, 28.

11 Weir 2018, 39.

12 Weir 2018, 59.

13 Weir 2018, 55.

14 Weir 2018, 40.

15 Meyer 2017, 64.

16 Meyer 2017, 60. “Our dance theatre does not provide any predetermined course, conflicts or solutions. It puts things to the test, explores processes. We enter into the feelings of others. We try to be open, we try – to put it bluntly – to feel.”

17 Meyer 2017, 66.

18 Weir 2018, 73.

19 Weir 2018, 21.

20 Weir 2018, 58.

21 Weir 2018, 60.

22 Weir 2018, 104.

23 Weir 2018, 40.

24 Weir 2018, 113.

25 Weir 2018, 159.

26 Weir 2018, 133.

27 Weir 2018, 133.

28 Weir 2018, 146.

29 Meyer 2018, 133.

30 Weir 2018, 193.

31 Weir 2018, 190.

32 Weir 2018, 110.

33 Meyer 2017, 5.

34 Meyer 2017, 5.

Literature

Birringer, Johannes. 1986. “Pina Bausch: Dancing across Borders.” The Drama Review: TDR 30 (2): 85–97.

Meyer, Marion. 2017. Pina Bausch: The Biography. London: Oberon Books.

Weir, Lucy. 2018. Pina Bausch’s Dance Theatre: Tracing the Evolution of Dance Theatre. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Contributor

Liisa Pentti

Liisa Pentti (MA, BSc) is a choreographer, dancer and pedagogue and the artistic director of Liisa Pentti +Co. Her work has been performed in Finland, Europe and Russia. Pentti has published numerous articles on dance in various publications since 1996 and has co-edited with Niko Hallikainen the anthology Postmoderni tanssi Suomessa? (2018).