The fusion of dance and audiovisual media is referred to in several different terms. In English, the art form is described as dance film, screen dance, video dance, physical cinema, dance for camera, etc. To this day, there is no single established term for the genre. The variety of used terms reflects the diversity of the art form, which is influenced by the orientation of the artists and whether the artist or the viewer approaches the medium more from the viewpoint of dance or film. Dance filmmakers may have a background in film or dance. In addition, dance film is created within other artistic disciplines, such as media arts, performance arts, music video art and interdisciplinary fusions.

We can refer to dance on canvas or for canvas, or even a dance of displays. This indicates the ontological looseness with which dance is interpreted and reveals the speaker’s view of the role of dance in this medium. A dance work can be recorded as such in an audiovisual form or re-edited as a film adaptation of a stage work, with the motive of creating a faithful reproduction of the dance work for the screen. Dance can be embedded in the film as a central narrative device or as a context, with the intention to create a film in which dance is one of the elements of expression and narrative. Dance – or rather the composition of movement – can also manifest itself as a sequence of moving images or as a montage of several image surfaces; as a choreography of images in video and media art.

Central to this ever-evolving art form is the fusion of dance and moving images into an artistic product, in which the range of methods of both art forms has been utilised in a variety of ways. Audiovisual and choreographic means are used to create rhythm, express a story and convey emotion, thus creating a linear continuum of time experienced in visual media, in which actions and movement expression play a significant role.

In Finnish, tanssielokuva (dance film) is perhaps the most commonly used term, although other terms are also used, such as dance video, experimental film and physical cinema. These terms have strong cultural and contextual connotations and are associated with different art forms. In this text, the term “dance film” is used in its broad sense, covering all the different interpretations and fusions of dance and moving images.

Parallel History of Dance and Cinema

The relationship between dance and film has historically been very close. In the first experiments with moving images, dance played an important role. Among the pioneers of film, both Thomas Edison (1896) and the Lumière brothers (1899) filmed dancers performing in the style of Loïe Fuller’s Serpentine Dance.[1] Interesting moving figures, dancers, acrobats and other physical performers were the subject of many early cinematic explorations and documentations.

With the development of the cinema projector, editing and sound film, the film industry developed and cinema quickly became a commercially significant medium and popular entertainment. In the silent films of the 1920s, physical expression still played a significant role. Initially, incorporating sound into the film was not so satisfactory, so movement, gestures and actions played a major role in the storytelling and emotional expression. Good examples of this are the films of the early American silent heroes Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin, which represent pure physical storytelling in cinema in their means of expression.[2]

With Sound Comes Dance

With the arrival of sound in the 1930s, musical films quickly became a major film genre. In Hollywood’s commercially successful musical comedies, dance and music played a central role. Musical films, which feature dance mainly as uplifting musical numbers, can be divided into two categories: backstage musicals and integrated musicals. In a backstage musical, the story takes place mainly in the world of theatre or dance. The storyline locates the dance where it would take place in the real world, such as in rehearsal halls or on stages. Such films include 42nd Street (1933), Cabaret (1972), Moulin Rouge! (2001) and Burlesque (2010). Dance and music scenes can also be elements that drive the story, which is called an integrated musical. In these, the characters break out into dance and song in the middle of the story, at the locations where it takes place. Integrated musical films include Singin’ in the Rain (1952), West Side Story (1961), La La Land (2016); many Disney animations, such as Beauty and the Beast (1991) and Frozen (2013); as well as numerous films by director-choreographer Busby Berkeley,[3] who has been called the forefather of the form.

There is no clear-cut genre boundary, and a film can have both backstage and integrated elements, as in the classic Singin’ in the Rain, where the characters work in the theatre industry, but their emotional states are expressed through dancing and singing, such as in Gene Kelly’s famous singing and dancing scene in the street.[4]

In dance films that are dramas, the events are often set in some way in the world of dance, but the dance itself plays a central role in driving the narrative, such as in Flashdance (1983), Dirty Dancing (1987), Billy Elliot (2000), StepUp (2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2019) and Black Swan (2010). Ballet and opera films are a genre of their own, often with music as a pervasive element, as in the classic films Red Shoes (1948), The Tales of Hoffmann (1951), and Carlos Saura’s flamenco films Blood Wedding (1981), and Carmen (1983), which rely on the expressive power of flamenco.

One specific type of musical film is Indian Bollywood film, where dance and song numbers are part of the narrative and the film often has characteristics of the musical, such as clarity of emotion, a sense of community and a happy ending. A particular feature of Bollywood films is the presence of musical numbers in almost all film genres, from drama to comedy, thrillers and action films.

The Oxford Handbook of Dance and the Popular Screen,[5] edited by Melissa Bianco Borelli, is an excellent anthology that unpacks the different manifestations of dance and the implications and representations of the moving body in popular cinema. The book examines both well-known films and popular media from the perspectives of the embodied cultures and identities they construct and reinforce. Several dance dramas exploit ideological confrontations and construct drama by exaggerating socioeconomic, cultural, art political, gender, sexual or ethnic binaries. In popular films, dance often represents a pathway to liberation, change or growth, or serves as a broader sociopolitical metaphor, as in Dirty Dancing, Flashdance, Black Swan and Billy Elliot. The authors of the anthology analyse the layers of representation embedded in mainstream media. Story, characters, genre of dance, quality of movement and the way it is portrayed guide our interpretation and often reinforce binary ideologies. Envisioning Dance on Film and Video, edited by Judy Mitoma,[6] is also a comprehensive overview of the development of dance in predominantly US cinema in the 20th century. The collection of essays provides illuminating insights into the practice of making dance films.

Experimental Cinema

The Ukrainian-born filmmaker, researcher, poet, and dancer-choreographer Maya Deren was one of the most important artists of the new avant-garde and experimental cinema that began in the 1940s. She researched and developed shooting and editing techniques and created her own definitions of dance cinema. She was one of the first theorists of dance film, and her influence continues to resonate not only in film but also in studies of feminist theory, culture and psychology.[7] Her film essay A Study in Choreography for Camera (1945) and the accompanying texts on film theory highlighted three main features of the relationship between the camera and dance:

- Film liberates choreography from time and space: a scene can start in one place and continue naturally in another.

- Film can create a super dancer: for example, a jump can be longer or higher than usual, or a pirouette can spin for minutes

- When making a dance film, the theatrical space must be forgotten: as time changes, so does the focus of the viewer and the meaning of the environment.[8]

Postmodern Dance and Cinema

With the rise of postmodernism in the 1960s, dance and visual artists became interested in the possibilities of the moving image. Prominent figures in American modern dance turned to cinematic expression, including Merce Cunningham and Yvonne Rainer.

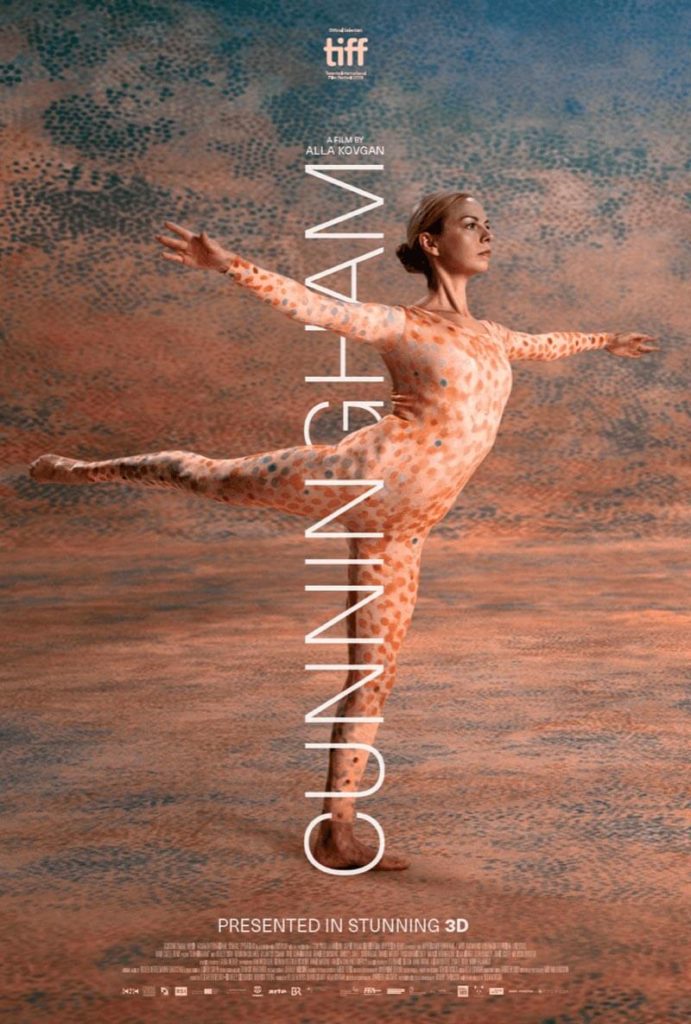

Merce Cunningham incorporated moving images creatively into his stage works but made film adaptations of his choreography, and produced film and video works. Cunningham had a long-lasting creative partnership with the avant-garde music composer John Cage, and his work had a major impact on postmodern dance, including dance cinema. Cunningham’s collaboration with film and video artists such as Eliot Caplan,[9] Nam June Park[10] and Charles Atlas produced a number of important experimental works that fused dance, visual language and music. The collaboration with Atlas began with early video works in the early 1970s and continued until the 2010s.[11] Atlas also directed the documentary Merce Cunningham: A Lifetime of Dance (2000), which includes documentary footage and film adaptations of Biped and Pond Way. The most recent documentary, Cunningham (2019), directed by Alla Kovgan and completed posthumously, focuses on the early decades of Cunningham’s career and features a wealth of unprecedented footage, as well as visually stunning new stereoscopic film adaptations of as many as 14 of Cunningham’s works performed by the company’s dancers.[12]

In his choreographies, Cunningham emphasised the freedom of the viewer’s gaze and interpretation and the autonomy of movement. What mattered to him was the movement itself and the dancer’s interpretation of it. When working with film, he paid close attention to the size of the frame and the potential viewing platform (television, film canvas or stage) in order to best convey the dance to the viewer in each medium.[13]

One of the key artists of the postmodern dance and experimental film movement that began in the 1960s, Yvonne Rainer is one of the leading figures in the field. Even in her early choreography, she combined movement, text and visual expression to create ambiguous but expressively rich works.

Emerging feminist film theory and the potential of experimental narrative led Rainer to move towards film in the early 1970s.[14] Her first feature-length fiction film, Lives of Performers (1972), is an intimate, complex exploration of performativity. The themes of Rainer’s films interweave her personal experiences and life events with their underlying themes and characters. In her films, she has drawn on her personal experiences of discrimination, sexuality, illness and artistry, filtering them through her own feminist values and experimental aesthetic, breaking the narrative and structural conventions of film.[15]

Rainer’s films contain a lot of layered, textual ambiguity and are obscure, dryly comic, furious and fragmented, but simultaneously intimate and associatively ambitious.[16] Her feminist films address a range of injustices, from age and gender discrimination to mental illness. In her films, which blur the line between fiction and documentary, dance and artistry are present, often through characters and events, as in Lives of Performers, or in scenes set within dance. For Rainer, body and movement are one of many ways to expand associative cinematic expression and avoid straightforward narrative. Yet Rainer has never abandoned dance and returned to it in the 2000s. Even today, mainstream cinema lacks filmmakers like Rainer who challenge the dominance of narrative and characters, and whose work takes the political beyond the means of film and the way the camera views individuals, especially women.[17]

One of the pioneers of Finnish experimental cinema, visual artist Eino Ruutsalo, created The Eagle (Kotka, 1962) in collaboration with Riitta Vainio, a pioneer of modern dance. The Eagle was the first Finnish short dance film to be produced. It is a visually minimalist, graphic film about the longing for freedom, relying on the expressive expression of the dancer and Otto Donner’s percussive score. The collaboration between Ruutsalo and Vainio continued in the artist’s film The Junk Artist (1965). Ruutsalo also made Kinetic Pictures (1962), based on the manipulation of film emulsion, in which painting, scratching and other editing techniques created a stream of abstract, dynamically moving images. Kinetic Pictures is a classic work of modern experimental cinema, where the movement of the image can also be seen as a kind of dance. It is now also part of the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Pompidou Centre in Paris.[18]

A New Era of Dance Film from the 1980s

The breakthrough of music videos and the development of video cameras in the 1980s influenced the aesthetics of contemporary dance film. The short format of commercial music videos introduced a new way of shooting and rapid-tempo editing, as well as a range of visual effects. The audience quickly expanded through Sky, MTV and other TV channels. Dance artists and choreographers soon adopted video as a medium of expression, and new short dance film formats became more widespread. Along with new creators and forms of expression emerged new production funding and distribution platforms for dance film. The BBC and Channel 4 in the UK, for example, produced several dance films which were shown on television in a dedicated slot. The synthesis of dance and film developed in increasingly diverse directions and reached new audiences. Film director David Hinton worked with the British physical theatre group DV8, adapting their stage works into a cinematic form. Hinton’s films Dead Dreams of a Monochrome Men (1990),[19] Strange Fish (1992)[20] and Touched (1994) paved the way for the later films produced by DV8, Enter Achilles (1995), directed by Clara van Gool, and Cost of Living (2004), directed by Lloyd Newson, in which the arc of drama is carried in an engaging way through physicality and dance.

Choreographers, filmmakers and composers have worked on many fruitful collaborations. Composer-director Thierry de May has directed several dance films[21] with Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker, one of the most known of them is Rosas danst Rosas (1997), a film adaptation of the 1983 premiered work of the same title. De May’s dance films with different choreographers are fascinating compositions of visual language and movement.[22]

With its rich creative language and emerging new talent, dance film also found its way into film and dance festivals, galleries and events dedicated exclusively to dance film. Several relatively small dance film festivals with varying lifespans and audiences have popped up around the world. The Finnish, Helsinki-based Loikka, held from 2008 to 2018, attracted widespread international interest and resulted in rapid growth of the filmmaking community and interest in dance film in Finland.[23] With the development of digital film formats and distribution channels in the 21st century, dance film has spread around the world, and is shown not only at festivals and on linear television but also on a variety of digital media platforms such as Vimeo, YouTube and even on subscription-based streaming channels. The sales and distribution of dance films remain a challenge, filmmakers, especially short and experimental filmmakers, rarely make a living from it alone. However, a high-quality dance film can circulate widely on the festival circuit, reaching large audiences and gaining visibility for the art form and its creators.

The history of Finnish dance film is still largely undocumented. In addition to Eino Ruutsalo, several artists have used dance expression in their film and video works. In 1972, the photographer Antero Takala produced a video work for television, Romeo and Juliet, based on electronically processed photographs of a ballet performance. Since the 1980s, media artist Marikki Hakola has made media art and video works featuring dance in collaboration with many key dance artists, such as Sanna Kekäläinen, Kirsi Monni, Ari Tenhula (Piipää, Cricket, Telephone, Gyrus), Soile Lahdenperä (Lucy in the Sky), Ismo-Pekka Heikinheimo (TransVersum), Jyrki Karttunen, Alpo Aaltokoski (Enchanted Child), Nina Hyvärinen (Luonnotar) and Johanna Nuutinen (Mirages).[24] Director Joe Davidow [25] has made dance films with choreographer-dancers Jorma Uotinen and Carolyn Carlsson, and dance artist Rea Pihlasviita formed a creative partnership with video artist Kimmo Koskela, making several dance videos and films in the 1990s. Film directors Saara Cantell, Kiti Luostarinen, Pia Andell and Samuli Valkama and multimedia artists Milla Moilanen, Kim Saarinen and Marja Helander have made interesting and award-winning dance films. Among dance artists, Mikko Kallinen and Hanna Brotherus have made their mark in dance filmmaking in the 2000s, as have several other Finnish dance artists. Kimmo Alakunnas was the first student in higher education to complete his Master’s programme in choreography thesis with a dance film (Ant, 2010).

Diversity of Cinematic Expression

Modern short dance films represent a wide variety of cinematic genres and forms. They can be story-driven, animated, documentary, with experimental visual narratives and intensely kinetic. Their stories or atmospheres can include drama, humour, horror, science fiction and musical escapism. Nor does the narrative of a dance film exclude any dance genre or style. Ballet, tap, street dance, jazz, flamenco, contemporary dance and various ethnic and folk-dance styles are widely represented in dance films. Rather than a classification based on the form or genre of film or dance, it is perhaps more meaningful to look at the modes of bodily and cinematic expression utilised in dance films.

Many dance films make rich use of cinematic tools, with thoughtful, innovative and cutting-edge cinematography, the rhythm of editing and the use of sound. Hilary Harris’s sparse, brilliant film study Nine Variations (1966) is a classic example of how framing, composition and editing can influence the interpretation of dance. The film conveys the director’s choreographic thinking, which extends not only to the dance seen on screen but to all the techniques used in the film. In Liz Agis and Billy Cowie’s short film Motion Control (2002), the movement of the camera, the rhythm of the editing, the soundscape and even the colour scheme of the film create a strong dystopian choreographic whole, borrowing aesthetics from horror and science fiction and heightened by Agis’ powerful performance. A dance film can also build around a strong performer, as in Marline Millar’s The Greater the Weight (2008), in which the director has adapted Dana Michel’s stage solo work into a film and, through careful composition, allows the viewer to attend to the fierce richness of the dancer’s expression.

In addition to identifying with the story and conveying emotion dance films often seek to evoke kinetic empathy in the viewer. A film may seek to convey a kinaesthetic experience or even internal bodily sensations, such as the haunting but beautiful weightlessness in Julie Gautier’s Ama (2018), or physical governing of the powerful elements of nature, as in Sérgio Cruz’s Hannah (2010). A film can also convey the relationship between the body, space and animated elements within it, as Steven Briand does in his film Frictions (2011).

The location is also a vehicle for conveying meaning in films. Due to the limited production conditions for dance films and to reflect the embodied abstract expression of contemporary dance filmmakers often seek to use non-spaces in their productions. Cost-efficient non-spaces and ambiguous places, such as nature environments of forests, meadows and beaches; or public and urban spaces such as night streets, tunnels, factories and abandoned buildings, are so common in dance films they have become a cliché. Unfortunately, in doing so, filmmakers lose the opportunity to contextualise their film through a carefully chosen location. For example, when dozens of dance films are set in an empty warehouse or factory building, a new cinematic or contextual approach is hard to find. Finnish film Cold Storage (2016), a tragicomic and crisp short film by director Thomas Freundlich and choreographer Valtteri Raekallio, is set on an Arctic glacier – an unusual milieu that supports the film’s story – which has certainly contributed to the film’s exceptional success at festival circulation, with over 300 festival screenings.

Documentaries on dance and its creators are a separate genre. Dance documentaries range from short to feature-length documentaries, from personal portraits to introductions to different dance genres and series that explore dance as a form of expression, such as the BBC’s Move, produced in 2019, in which choreographer Akram Khaan leads the viewer into the world of dance. Among the auteur documentaries, Wim Wenders’ feature-length documentary Pina (2011) is worth mentioning. The film features excerpts dramatised for the film and stereoscopically filmed footage of several of Pina Bausch’s key works, with interwoven interviews of the company dancers. A dance film can also be autofictional, where the story is based on the life of the central character, but the narrative relies on choreographic and fictional cinematic methods, as in Kovgan’s and Hinton’s co-directed award-winning Nora (2008). The film’s choreographer and protagonist, Zimbabwean-born Nora Chipaumire, plays the characters in the poetic film, portraying her life before her exile and career in the West.

Today, dance is also present in advertising, video games and on a wide range of digital platforms. Contemporary ballet choreographer William Forsythe and director Thierry de May’s stunning short film One Flat Thing, Reproduced (2006) is an example of how dance film footage can be the springboard for new digital media. The multimedia website Synchronous Objects uses film footage to digitally visualise and analyse the choreography of the original dance piece. A subsequent website, Motion Bank, also uses a wide range of visual material to analyse and visualise the work and methods of major contemporary dance practitioners. These new media-based sites are based both on various forms of recordings of dance works and on even interactive visualisations that unlock the choreographic principles of the works.

Technological innovations in recent decades, such as 360° cameras, digital manipulation of images and motion capture digitised into virtual formats, are constantly enabling dance and movement to take on new forms and dimensions in audiovisual media. Popular entertainment, films, games and virtual content draw inspiration from dance, as exemplified by the combat sequences seen in The Matrix (2006), where otherworldly slowdowns, tilts, leaps and lunges create their own recognisable movement language. There is no discernible endpoint to this path of influence, borrowing and inspiration; the digital manipulation of bodies, playing with realities and choreographic thinking continue in different contexts and media, expanding the transmedial field of dance.

The roads to becoming a dance filmmaker and director can be manifold. Many choreographers work on film alongside their stage work, but some end up working entirely in film. Busby Berkeley, Gene Kelly and Bob Fosse, who started out as artists in dance, gained a foothold as film directors through their work in film choreography, setting an example and paving the way for their successors. The path of several dance artists has led them towards a diverse audiovisual field, opening opportunities for script writing, screen choreography, cinematography and directing. Finnish artists, such as Kati Kallio and Thomas Freundlich, who both started out as dancer-choreographers, have pursued a career working almost exclusively in visual media.

Today’s dance filmmaker needs to study the history, tools and language of film, as well as the art of dance, and find their own distinctive aesthetic through practice. The field has expanded beyond stand-alone courses to academic education, with the launch of a Master’s programme at The Place School in London in 2018. Curating and programming dance films is another area of expertise, and among curators, the lack and importance of cultural and historical contextualisation of dance films have become a topic of debate.[26] Yet, contemporary research and theorisation of dance cinema remain surprisingly thin, and film and dance studies have maintained a discreet distance from each other. However, in recent decades, an increasing number of notable publications and theoretical approaches have opened up the practice and history of dance filmmaking, which are recommended reading.[27]

Film is one of the many media where dance and movement expression can tell a strong story, convey emotions and evoke intense kinaesthetic experiences. The wide spectrum of compositional forms, the accessibility of digital tools, new distribution platforms and digital multimedia formats, have made dance film an increasingly significant hybrid art form, which more and more creators are drawn to. This is why it is constantly transforming and developing. Dance in audiovisual mediums is becoming increasingly diverse as the boundaries between art forms dissipate, the number of creators increases, new tools emerge and the possibilities for artists to envision a span of new expressive forms expand.

Notes

1 Loye (Loïe) Fuller (1862–1928) was an American-born pioneer of both modern dance and theatrical lighting techniques. As a vaudeville performer in the US, she developed her own improvisational dance numbers, in which she used light illuminating a rich silk fabric costume. The Serpentine Dance developed by Fuller in 1891 attracted attention and caused many to imitate the style. Hoping for recognition and independence, Fuller soon moved to Europe, where she continued her experiments with lighting and cloth, which she later patented. After settling in Paris, she became the embodiment of the art nouveau movement. Visually impressive, symbolist solo works were well suited to cinematic experiments and treatises. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loie_Fuller

2 The term physical cinema is still used to describe a film that focuses on physical expression as it main narrative tool. It has its roots in the tradition of Vaudeville Theatre, often with exaggerated comical characters and events.

Keaton: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buster_Keaton, a study on Keaton physical comedy; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWEjxkkB8Xs,

Chaplin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Chaplin; Modern Times 1936: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GLeDdzGUTq0,

Lloyd: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_Lloyd; Safety Last 1923: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFBYJNAapyk.

3 Berkeley’s filmography includes more than 50 films which he directed and for which he choreographed musical numbers. He became known for his extravagant musical numbers and developed his own cinematic techniques to create visually stunning, choreographed scenes with dozens of performers. A compilation of kaleidoscopic scenes from the Warner Bros. archives can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PNCwYuXndP0&t=86s

4 Singing in the Rain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D1ZYhVpdXbQ

5 Borelli, Melissa. Bianco. (ed.) 2014. The Oxford handbook of dance and the popular screen. Oxford University Press, USA.

6 Judy Mitoma, Elizabeth Zommer, Dale Ann Stieber. 2002. Envisioning Dance on Film and Video. Psychology Press.

7 Kappenberg, C. & Rosenberg, Douglas. 2017. “After Deren”. The International Journal of Screendance, 3.

8 Deren, Maya. 2005. Essential Deren; Rosenberg, D. 2012. Screendance: Inscribing the ephemeral image.

9 For example cinematic works Points in Space (1986), Beach Birds for Camera (1991/1993): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fq2r7kUu-nM.

10 Works such as Merce by Merce by Paik part One and Two (1975 & 1978).

11 Long collaboration with Atlas produced experimental videos and film versions of stage works, such as Walkaround Time (1973), Channels/Inserts (1982), Coast Zone (1983), Pond Way (1998) Melange (2000), Interscape (2001) and Ocean (2010).

12 New stereoscopic film adaptations of works in recent Cunningham films are: Suite for Two 1950s, Septet (1953), Suite for Five (1956), Antic Meet (1958), Summerspace (1958), Rune (1959), Crises (1960), Aeon 1961, Winterbranch (1964), Rainforest (1968), Canfield (1969), Tread (1970), Second Hand (1970).

13 Lee, Eun Yi. 2013. The Emergence and Definition of Screen Dance; Shanahan, Eamonn B. 2014. SCREEN DANCE – THE GENESIS OF AN ART FORM; Mitoma, J. 2002. Envisioning dance on film and video.

14 Rainer discusses her reasons for turning to film in many interviews. One video interview is on Artforum: https://www.artforum.com/video/interview-with-yvonne-rainer-2011-29229. Carol Armstrong and Catherine de Zegher in Women Artists at the Millennium (2006, 5) cite Rainer: “I made the transition from choreography tofilmmaking between 1972 and 1975. In a general sense my burgeoning feminist consciousness was an important factor. An equally urgent stimulus was the encroaching physical changes in my aging body.”

15 Brechtian Journeys: Yvonne Rainer’s Film as Counterpublic Art. Art Journal, 68(2), 76–93.

16 Rainer’s films: Lives of Performers (1972), Film About a Woman Who… (1974), Kristina Talking Pictures (1976), Journeys from Berlin/1971 (1980), The Man Who Envied Women (1985), Privilege (1990) and MURDER and murder (1996).

17 Lucca, Violet. 2017. “MOVING BEYOND.” Film Comment 53, no. 4: 42.

18 Taanila, Mika. 1985. Seitsemännen taiteen sivullisia – Kokeellinen elokuva Suomessa 1933–1985. (The Outsiders of the Seventh Art – experimental film in Finland 1933–1985).

19 Dead Dreams of a Monochrome Man: https://www.dv8.co.uk/projects/archive/dead-dreams-of-monochrome-men–film

20 Strange Fish: https://www.dv8.co.uk/projects/archive/strange-fish–film

21 Films of collaboration of De May and Keersmaeker: 21 etyds for dance (1989): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yqin4Q7oKKE, Hoppla (1989): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qTOlNcZAJ5A, Achterland (1990): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bW_k06Vtcko

22 Film works of De May with other choreographers: Dom Svobode kor. Iztok Kovac, Musique de tables kor. Vim Vandekyebus and One Flat Thing Reproduced, chor. Forsythe.

23 Hanna Pajala-Assefa founded the Helsinki-based Loikka dance film festival in 2008. The festival was the first annual event for dance film viewers and artists to convene in Finland. The festival organised workshops with invited international mentors and influenced the rapid growth of the dance film scene during the early 21st century. At the festival’s tenth anniversary in 2018, in addition to film screenings the festival showed a programme of movement and dance oriented virtual works and organised an international conference for filmmakers and curators.

24 Works by Marikki Hakola: https://www.kroma.fi/category/dancefilm/ ja https://www.mirages.fi.

25 Davidow: https://www.joedavidow.com/dance_drama_films.php.

26 Douglas Rosenberg in Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image (2012) discussed the commercial curatorial needs of festivals to survive, which places the films in a historical and contextual void.

27 Katrina McPherson, Making Video Dance (2006), a basic guide to creating dance filmmaking practices (new, edited version published 2018); Sheryll Dodds, Dance on Screen: Genres and Media from Hollywood to Experimental Art (2001), a historical and analytical work; Judy Mitoma, Envisioning Dance on Film and Video (2002), records the history of dance and the moving image and gives space to the perspectives of the creators. The most recent books dealing with the subject are Erin Brannigan’s Dancefilm: Choreography and the Moving Image (2010), which aims to synthesise the theories of film and dance and take into account the intersecting effects of the arts on dance film, and Douglas Rosenberg’s Screendance: Inscribing the Ephemeral Image (2012), which critically examines the field of dance film. There are also numerous conference publications, articles and treatises on dance film topics.

Literature

Armstrong, Carol & Zegher, Catherine de. 2006. Women Artists at the Millennium. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Borelli, Melissa. Bianca. (ed.). 2014. The Oxford handbook of dance and the popular screen. Oxford University Press, USA.

Brannigan, Erin. 2010. Dancefilm: choreography and the moving image. Oxford University Press.

Deren, Maya. 2005. Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film by Maya Deren, edited by Bruce R. McPherson. New York: Documentext.

Glahn, Philip. 2009. Brechtian Journeys: Yvonne Rainer’s Film as Counterpublic Art. Art Journal, 68(2), 76–93.

Kappenberg, Claudia. & Rosenberg, Douglas. 2017. After Deren. The International Journal of Screendance, 3.

Lee, Eun. Yi. 2013. The Emergence and Definition of Screen Dance. 현대영화연구논문[Contemporary Film Studies], 16.

Lucca, Violet. 2017 ”MOVING BEYOND.” Film Comment 53, no. 4: 42.

McPherson, Katarina. 2006/2018. Making video dance: a step-by-step guide to creating dance for the screen. Routledge.

Mitoma, Judy. 2002. Envisioning dance on film and video. Psychology Press.

Rosenberg, Douglas. 2012. Screendance: Inscribing the ephemeral image. Oxford University Press.

Shanahan, Eamonn B. 2014. SCREEN DANCE – The genesis of an art form. Thesis for Crawford College of Art & Design

Taanila, Mika. 1985. SEITSEMÄNNEN TAITEEN SIVULLISIA – Kokeellinen elokuva Suomessa 1933–1985, artikkeli suomalaisen kokeellisen elokuvan historiasta https://mikataanila.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/7-taiteen-sivullisia.pdf

Online Sources

Artforum. Interview with Yvonne Rainer from 2011. Website: https://www.artforum.com/video/interview-with-yvonne-rainer-2011-29229 Accessed 21.4.2021.

EAI Electronic arts intermix. Online archive of video and media arts. https://www.eai.org/artists/merce-cunningham/titles Accessed 6.4.2021.

Gadsby, Ruby, Gray, Ruby, Kronkop, Tal & Pendlebury, Molly Ann. Four films by MA students in dance film https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sgnu4KjsMLI&t=2102s Accessed 10.2.2021.

London Contemporary Dance School, MA in Screendance. Website: https://www.theplace.org.uk/ma-screendance-0 Accessed 10.2.2021.

Magnolia Pictures. Cunningham film website: https://www.cunninghammovie.com Accessed 20.3.2021.

Magnolia Pictures. Press kit of the Cunninham film: https://www.magnoliapictures.com/cunningham-press-kit Accessed 20.3.2021.

Motion Bank. Contemporary Dance website: http://motionbank.org Accessed 15.3.2021.

Senses of Cinema; Maya Deren. Website: http://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/deren-2/ Accessed 21.4.2021.

Synchronous Objects. Website: https://synchronousobjects.osu.edu Accessed 15.3.2021.

Synchronous Objects. Video of visualisations of the work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v2REtWg6-bo Accessed 15.3.2021.

Films

Dead dreams of a Monochrome Man. Directed by David Hinton, based on stage performance by Lloyd Newson. Edited by John Costelloe, starring Lloyd Newson, Nigel Charnock, Russell Maliphant, Douglas Wright. Produced by Vijay Armani and David Hinton. UK, 1990.

Strange Fish. Directed by David Hinton, film adaptation by Hinton and Newson based on Lloyd Newson’s stage performance Strange Fish. Photographer Nic Knowland, editor John Costello, performers Kate Champion, Nigel Charnock, Jordi Cortes Molina, Wendy Houstoun, Diana Payne-Myers, Melanie Pappenheim (vocals), Lauren Potter, Dale Tanner. Produced by David Stacey/DV8. UK, 1992.

One Flat Thing reproduced. Directed by Thierry De Mey, choreography by William Forsythe. Dancers in the Forsythe company: Yoko Ando, Cyril Baldy, Francesca Caroti, Dana Caspersen, Amancio Gonzalez, Sang Jijia, David Kern, Marthe Krummenacher, Prue Lang, Ioannis Mantafounis, Jone San Martin, Fabrice Mazliah, Roberta Mosca, Georg Reischl, Christopher Roman, Elizabeth.

Waterhouse. Directed by Ander Zabala. Production MK2TV / ARTE France / The Forsythe Company / Forsythe Foundation / ARCADI / Charleroi Danses. https://www.numeridanse.tv/en/dance-videotheque/one-flat-thing-reproduced France, 2006.

Motion Control. Directed by David Alexander Anderson, choreography by Liz Aggiss and Billy Cowie, cinematography by Simon Richards, editing by Mark Richards, music Billy Cowie. Produced by Arts Council of England & BBC, Producers Bob Lockyer (BBC) and Rodney Wilson (Arts Council of England). https://vimeo.com/316804174 UK, 2002.

The Greater the Weight. Directed and produced by Marlene Millar and Philip Szporer, choreography and dance by Dana Michel, cinematography by Bill Kerrigan, editing by Dexter X. Produced with the support of The Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec and Bravo!FACT. Trailer: https://vimeo.com/23335298 Canada, 2008.

Ama. Directed by Julie Gautier; choreography by Ophélie Longuet, s cinematography by Jacques Ballard, edited by Jérôme Lozano, music ‘Rain in your black eyes’ by Ezio Bosso, Sony Music Entertainment. Produced by Spark Seeker/Les Films Engloutis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bdBuDg7mrT8 France, 2018.

Hannah. Directed, produced, edited and sound designed by Sérgio Cruz, cinematography by Dominik Rippl, Sérgio Cruz and Tom Ellis, performer Hannah Dempsey. Production support South East Dance, Calouste. https://vimeo.com/44534411 UK, 2010.

Friction. Directed by Steven Briand and Julien Jourdain de Muizon, choreography by Clara Henry, cinematography by Pierre Yves Dougnac, music and sound design by Moritz Reich & Agathe Courtin, visual effects by Francis Cutter & Benoit Masson, animation by Natalianne Boucher, Camille Chabert, Luca Fiore, Sarah Escamilla. https://vimeo.com/29220752 France, 2011.

Cold Storage. Directed and cinematography by Thomas Freundlich, choreography by Valtteri Raekallio, music by Kimmo Pohjonen, editing by Jukka Nykänen, dance by Eero Vesterinen and Valtteri Raekallio. Produced by Aino Halonen. Production support Finnish Film Foundation (SES), YLE, Loikka dance film festival, Jenny and Antti Wihuri Fund, Finland, 2016.

Nora. Directed by Alla Kovgan and David Hinton, choreography by Nora Chipaumire, cinematography by Mkrtich Malkhasyan, editing by Alla Kovgan, producer Joan Frosch, performers Nora Chipaumire, Souleymane Badolo and several assistants. Produced by EMPAC DANCE MOViES Commission 2007, supported by The Jaffe Fund for Experimental Media, Performing Arts – Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, USA. UK, USA, Martinique, 2008.

Ant/Ant. Directed, choreographed, script and scenography by Kimmo Alakunnas, cinematography by David Berg, edited by Tiina Aarniala and Kimmo Alakunnas, performed by Jaakko Nieminen and Kimmo Alakunnas. Produced by Teatterikorkeakoulu https://vimeo.com/76713611 Finland, 2010.

Other Film References

42nd Street (1933) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/42nd_Street_(film)

A Study in Choreography for Camera / MAYA DEREN (1945) https://youtu.be/Dk4okMGiGic

Billy Elliot (2000) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Billy_Elliot

Black Swan (2010) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Swan_(film)

Cabaret (1972) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cabaret_(1972_film)

Carmen / Carlos Saura ( 1983) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carmen_(1983_film)

Cunningham/Alla Kovgan, GR/FR/US, 93’ (2019) https://www.cunninghammovie.com https://www.imdb.com/title/tt8574836/

Dirty Dancing (1987) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dirty_Dancing

Film About a Woman Who… (1974) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0071497/?ref_=tt_sims_tt

Flashdance (1983) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flashdance

Frozen (2013) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frozen_(2013_film)

La La Land (2016) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_La_Land

Lives of Performers (1972) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0068865/

Merce Cunningham: A Lifetime of Dance/Charles Atlas, US/FR/UK, 90’ (1999) https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0316238/

Moulin Rouge! (2001) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moulin_Rouge!

Nine variations on a dance theme / Hilary Harris (1966/67) https://youtu.be/03Qa3KMxXWc

Pina (2011) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pina_(film)

Rosas danst Rosas (1997) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vlLZExpgBOY

Singing in the Rain (1952) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singin%27_in_the_Rain

Step Up (2006) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Step_Up_(film)

The Red Shoes (1948) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Red_Shoes_(1948_film)

The Tales of Hoffmann (1953) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Tales_of_Hoffmann_(1951_film)

Blood Wedding / Carlos Saura (1981) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blood_Wedding_(1981_film)

West Side Story (1961) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Side_Story_(1961_film)

Contributor

Hanna Pajala-Assefa

Hanna Pajala-Assefa (TeaK MA, choreographer 1995) is a dance artist and multimedia choreographer who focuses on choreography, dance film, exploratory innovative work and the mediated body at the interface of dance and new technologies. During her career, she has created over 40 dance works, dance films and multidisciplinary multimedia performance art productions, which have been seen around the world. Since 2013, she has worked in interactive audiovisual media and virtual technologies, as well as teaching and curating new media performance content. She is currently at the University of the Arts Helsinki pursuing a doctorate in arts on the choreography in mediated performance environments.