The Twentieth Century

Until the beginning of the twentieth century much of Java’s traditions of classical dance and theatre discussed above had been closely guarded treasures of the courts. Dance was mainly intended for court rituals, and its training was basically a means of educating the aristocracy and the court. The early years of the 20th century brought about a number of changes that have come to be called the “democratization of dance”.

In 1918 the first dance society, Kridha Beka Wirama, was founded in Yogyakarta to teach court dances to all, regardless of class. The idea was launched by the son of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, and the teachers included the best dance masters of the kraton. This marked the beginning of a still-active custom whereby the court traditions of Yogyakarta are taught in private dance societies to all who are interested, often for only a nominal fee.

At present, the societies receive part of their income from performances aimed mainly at tourists. The leading dance societies in Yogyakarta that actively stage performances are the kraton-related Dalem Pujokusuman and Dalem Notopraian associations.

Wayang Orang

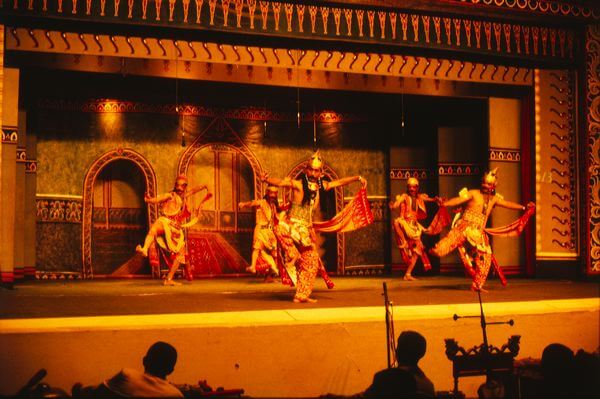

- Wayang orang is performed at the Sriwedari Theatre in Surakarta; wayang orang evolved from wayang wong but it is performed in contemporary language Jukka O. Miettinen

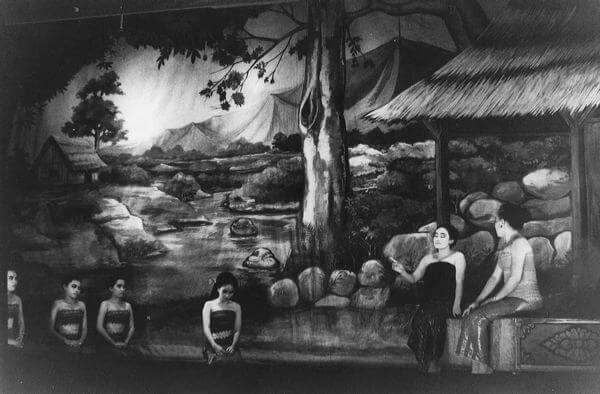

- Wayang orang makes full use of illusionist backdrops Jukka O. Miettinen

- The punakawan, servant clowns, in a wayang orang performance Jukka O. Miettinen

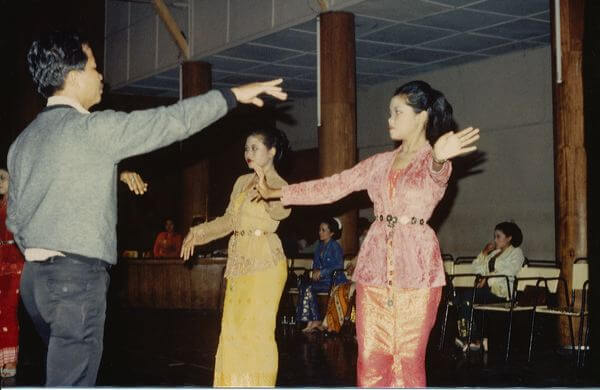

- In its movement techniques wayang orang follows the conventions of wayang wong Jukka O. Miettinen

The gradual popularisation of wayang wong began in Surakarta in the 1890s when a Chinese businessman founded a commercial group adapting the wayang wong tradition of the Mankunegaran kraton. This new style, generally referred to as wayang orang, was aimed at ordinary city audiences. The company, now under the name of Sriwedari, still performs in the amusement park in Surakarta. The Bharata Theatre, founded in the 1940s, has maintained this tradition in Jakarta.

Wayang orang is usually performed on a Western-type proscenium stage with heavy illusionistic backdrops, and an abundance of various stage effects. Commercial wayang orang groups are also active in the smaller towns, such as Semarang and Malang. Despite modernisation, wayang orang has preserved something of its original stylised dance-drama character.

Ketoprak and Ludruk

A drastic step towards Western stage realism and melodrama can recognised in the Central Javanese ketoprak and the East Javanese ludruk, which are forms of popular theatre evolved around the end of the nineteenth century. Their plots are based not only on the traditional stock stories from the Ramayana and the Mababbarata but also on historical or modern topics.

- Ketoprak combines stage realism, spoken text and music Jukka O. Miettinen

The performances are accompanied by music and include dance numbers, although the main emphasis is on a less stylised acting resembling Western spoken theatre. On the whole, stagecraft is similar to wayang orang, although there is even more of an emphasis on realism and even naturalism. Ketoprak and ludruk are still performed on temporary stages and in the theatre halls of amusement parks in various parts of Java.

Nationalism

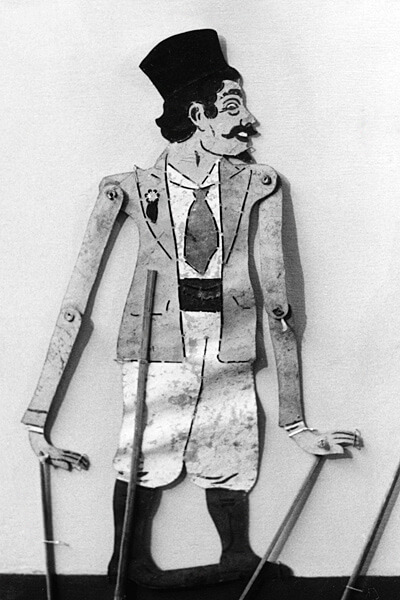

- Wayang pancasila was created during the early period of Indonesia’s independence and its puppets show political figures of the period Jukka O. Miettinen

The Indonesian nationalistic movement awoke during Dutch colonial rule in the 1920s and during the Japanese Occupation in the mid-1940s. After that, when Indonesia was in the process of gaining independence, even wayang kulit, the most traditional form of theatre, was used to propagate patriotism and new political ideas.

In the 1950s, the new nation, constructed of hundreds of ethnic groups, sought its identity, which was naturally also reflected in the arts. In the field of dance the new, nationalistic theatre organisations followed the model of the European socialist countries in transforming old traditions into new, “mass-oriented” variants, such as the peasant’s dance, the tea-picker’s dance, and the dance of the fishermen, as has been the case in many countries from the Soviet Union to China, to Cambodia etc.

Western-influenced Spoken Theatre

Western theatre and dance has begun to interest Indonesians to an increasing degree, and many artists have studied in the West, especially in the United States, since the 1960s. As in many Asian countries, so too in Indonesia the early interest in Western theatre and dramatists was concentrated in academic circles.

- Java has still many forms of folk theatre Jukka O. Miettinen

A student theatre group, called Studiklub Teater (STB), was founded in the university city of Bandung, in West Java, in 1958. Many of the some 60 dramatic works staged by STB were by Western writers, including Chekov, Gogol, Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams, Ionesco, Brecht, and Camus.

- In Sunda, in West Java, the popular music and social dance style is jaipongan Jukka O. Miettinen

STB was followed by several theatre groups, which aimed to reflect the rapid change in society and politics. In Jakarta Teguh Karya founded a group called Teater Populer. Teguh had studied in the West, and his work was dominated by realism and political idealism.

Realism, often with political overtones, was the trend in several other modern theatre companies. Bengkel Teater, founded by Rendra, was even a target of the government’s censorship in the 1970s. Political criticism was the aim of the Teater Kicil (Little Theatre), founded by Arifin C. Noer in 1968.

Some of the pioneers of modernism employed Indonesian styles and aesthetics in their work. One of them is Balinese Putu Wijaya, who founded Teater Mandir (Independent Theatre) in Jakarta. In his work Putu adapted Balinese theatre conventions to his experiments.

Yogyakarta, the old cultural and intellectual centre of Central Java, has also had several important early modern theatre groups. They include Teater Alam, Teater Dinasti, Teater Jepik, and Teater Gandrik.

Sendratari, The “Ramayana Ballet”

- Spectacular Sendratari Ramayana employs tens of dancers and modern stage technology Jukka O. Miettinen

In the early 1960s sendratari (seni: drama, tari: dance) was developed as yet another spectacular form of wayang wong -derived dance-drama. It had none of the patriotic fervour of the 1940s and 1950s, and was mainly intended for both Javanese and foreign tourists.

The first sendratari performance was staged by a group of artists from Yogyakarta and Surakarta in 1961. It was especially designed for an outdoor stage erected in front of the Hindu temple of Prambanan in Central Java with the temple’s enormous silhouette as its background. The choice of the theme and venue of this first sendratari production is self-evident: the Prambanan temple area is one of Java’s main tourist attractions and it is also related to the Ramayana through its early series of reliefs.

The Prambanan spectacle has come to be known as the “Ramayana Ballet”. This is indeed an apt name for a genre where the overall dramaturgy with its impressive mass scenes and modern stage techniques is modelled after the practice of Western fairy-tale ballet.

- Prince Rama in Prambanan Sendratari Ramayana Fredrik Lagus

The Ramayana Festival was for a long period a yearly event, performed at the time of the full moon from May to October. The scenes and events of the epic are divided into four full-evening performances. The Abduction of Sita is presented on the first night, followed by Hanuman’s Mission to Lanka, The Conquest of Lanka, and finally the fall of Ravana and the proof of Sita’s marital fidelity.

The sendratari of Prambanan turned out to be a success, perhaps partly because of the growing tourist industry focusing on Central Java. It has become an obligatory event for tour groups, and the previous modest stage has been replaced by a luxurious amphitheatre.

The “Ramayana Ballet” served as a model for later sendratari productions, which were staged in other parts of Java at sites of touristic interest. While the Prambanan ballet was mostly based on the Central Javanese heritage, the stories and dance styles of later innovations are based on their respective local traditions.

Near Surabaya in East Java there is a huge open-air stage with a perfectly conical volcano in the background. It was especially built for a sendratari production based on an East Javanese story combining in its presentation East Javanese and Balinese elements.

- Local sendratari production in Cirebon, West Java, employs the West Javanese style of dance Jukka O. Miettinen

In Cirebon in West Java, the local sendratari is staged in front of an ancient stone garden, and its dance style is based on local topeng dances. As a kind of Pan-Indonesian state art, the sendratari has also been adopted outside Java, for example, in Bali, where the first Balinese Sendratari Ramayana was staged in 1965.

Modern and Contemporary Dance

Western classical dance technique, ballet, had already found its way to Java in the 1940s, mainly through Dutch ballet teachers. A decade later modern Western dance also started to interest young Indonesian artists. One of the pioneers of Indonesian modern dance was Jodjana, who in his work focused on individualism and personal impressions, aspects, which were not emphasised in the traditional dance of Java.

Another pioneer was Seti-Arti Kailola, who went to study in New York at the Martha Graham studio, one of the leading institutes of American modern dance. In Jakarta she set up her own school, thus establishing the long-lasting link between the Graham technique and Indonesian modernism. The Graham technique and aesthetics were also explored by other choreographers, such as Bagong Kussudiardja and Wisnoe, who in their turn established their own dance studios by the end of the 1950s.

Another pioneer of Indonesian modern, or more appropriately contemporary, dance, who studied in New York, is Sardono (W.Kusumo). He had a background in classical Javanese dance and he started his exceptional career as one of the star dancers in the Pramabanan Sendratari Ramayana.

He established his own Sardono Dance Theatre in 1973. He has worked with artists and styles from different regions of Indonesia and has thus been instrumental for the experiments and innovations later done around the whole country. His works include, among others, environmental and site-specific productions.

- Dharmawan Dadyono performing his contemporary choreography based on the Central Javanese classical dance technique Jukka O. Miettinen

Several governmental institutions founded since the 1960s have had a decisive role in the development of Javanese as well as Pan-Indonesian dance and theatre. The establishment of the Jakarta Arts Centre Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) in 1968 has provided an arena for contemporary as well as traditional arts.

The Jakarta Arts Institute, which was opened in 1970, provided further opportunities for both art teachers and students. In 1978 TIM initiated the Young Choreographers’ Festival, which serves as a platform for choreographers and dancers working in the field of contemporary dance around Indonesia.