Regional Operas

An Abundance of Opera Styles

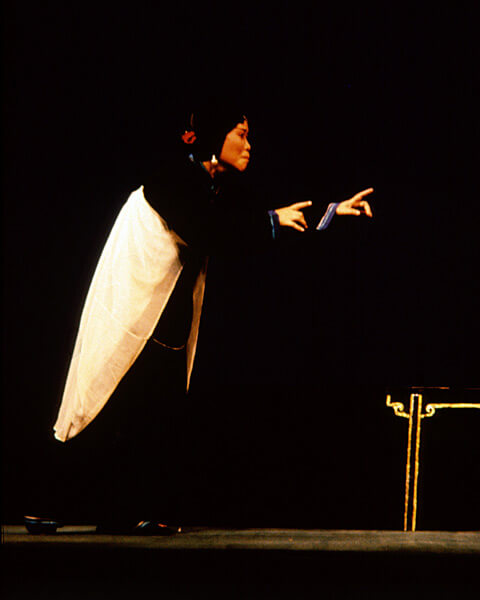

- A scene of the regional opera of Fujien. Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene of the regional opera of Fujien. Jukka O. Miettinen

Around China there is a plenitude of different styles of regional operas. These regional or local operas are called difangxi (ti-fang-hsi). According to different estimations and ways of classification, their number varies from approximately 100 to 360. They differ mainly in their dialects and in music and in their accompanying orchestras. Differences can also be found in their repertoire, character categories, costuming and make-up conventions etc.

- A scene of the regional opera of Fujien. Jukka O. Miettinen

Kunqu came first, and then the Peking opera attained the status of a “national style”. Although kunqu was originally a southern opera style and Peking opera at the beginning a predominantly northern style, they both gradually spread around the country. Local operas, however, bear characteristics of the dialects and melodies of certain provinces, and although they can occasionally be seen elsewhere as well, they are mainly performed in the areas where they were created and developed. In this connection only a handful of regional styles can be discussed.

Bangzi Opera or the Clapper Opera

Bangzi opera (bangzi qiang, pang-tzû ch’iang) or the clapper opera was probably created in Central China, in the border area between the provinces of Shaanxi (Shen-shi) and Shanxi (Shan-shi). It is mentioned for the first time in literary sources in the 16th century. It seems possible that in the beginning it was a style performed only in a very small area, but it spread in the 17th century to North and South China as well.

As has been discussed before, Chinese is a tonal language and thus, when it is sung, its relationship with the accompanying music is symbiotic. The tones, according to whether they are level, ascending, or first descending and then ascending, or descending in pitch, affect the actual meaning of the word. In some Chinese operas, the text is usually written for stock melodies that already exist. In the clapper opera, however, the text is written first and then the music is composed to suit the text. This gave greater freedom for rhythmic patterns as well as to the verses employed.

A dominant instrument in the orchestra accompanying the clapper opera is the bangzi (pang-tzû) clapper, a small, rectangular plate made of date palm, which is beaten with a wooden stick. The orchestra also includes string and plucked instruments. The most important melody instrument is a wooden banhu (pan-hu) violin. The vocal technique is regarded as more mellow and natural than the singing in the Peking opera. The costumes of the clapper opera, similarly as in the Peking opera, are based on Ming-period dresses.

The clapper opera is still widely performed today, particularly in North China, where several local variants of it have evolved. The most famous clapper opera actor ever was Wei Changsheng (Wei Ch’ang-sheng), who became a star actor in Peking in the late 1770s and early 1780s, just before the Peking opera was born. He was a celebrated impersonator of female roles, and was later also able to include amazing acrobatics in his performances.

Yue Opera, All-Female Opera

- A scene from a famous yue opera, Butterfly-Lovers. Jukka O. Miettinen

Yue opera (Yüeh-chü) or Shaoxing opera (Shao-hsing-chü) is the most recent form of the regional opera styles in China. In fact, because of its great popularity around China, it could almost be regarded as a kind of national style today. It originates from the indigenous music theatre tradition of a small locality called Shaoxing (Shao-hsing), near Shanghai, in the early 20th century. Its local folk melodies were accompanied by a simple ban (pan) clapper.

In 1916 a troupe led by an actor called Wang Jinshui (Wang Chin-shui) started to perform this type of theatre for the many Shaoxing people living in Shanghai. Its orchestra was gradually expanded to include plucked instruments and later even other kinds of instruments, although the melodies performed still originated from the Shaoxing region.

- A scene from a famous yue opera, Butterfly-Lovers. Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from a famous yue opera, Butterfly-Lovers. Jukka O. Miettinen

The performances were successful, but it was only in 1923 that yue opera began to take on its dominant characteristics. It was then that female singer-actresses started to be trained. From 1929 onwards all-female troupes appeared in Shanghai, and the novelty that operas were performed by all-female casts was an instant and long-lasting success, and it is still the trademark of the yue opera. This practice is due to the fact that mixed groups, including both male and female actors, were forbidden during the Qing (Ch’ing) dynasty (1644–1911), and it was only in 1930 that actresses could finally appear on the Peking opera stage.

- A scene from a famous yue opera, Butterfly-Lovers. Jukka O. Miettinen

The stories staged as yue operas are mostly romantic love stories. Acrobatics and fighting scenes were rarely included in them in older times. Today male actors may also play some of the roles of elderly men, while the young men’s roles are generally preformed by actresses. Fighting scenes and acrobatics are now also sometimes adopted from the Peking opera practices. On the modern yue stage sets with sugary-sweet painted backdrops are often used, and the costuming tends to represent a kind of semi-historical fantasy style in pastel colours. Yue opera was added to UNESCO list of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2009.

Well-known stories performed in the yue style include Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai (Liang Shan-po yü Chu Ying-t’ai) or The Butterfly Lovers. It is a kind of Romeo and Julia story about young love, which cannot find fulfilment. An early movie based on a yue version of this story was the first opera film produced in China. Other romances often seen on the yue stage include The Dream of the Red Chamber (Honglou meng, Hung-lou meng) and The Romance of the Western Chamber (Xixiang ji, Shi-hsiang chi).

Canton Opera

The western term “Canton opera” refers to an opera style typical of the region of the southern coastal city of Guangdong, also called Canton. The Chinese name of this style is, when written in Latin script, the same as the name of the all-female yue opera, i.e. yueju (Yüeh-chü). In Chinese, these names are, however, written differently. To avoid confusion, only the name “Canton opera” is used here.

- Canton opera performed on a modern stage. Jukka O. Miettinen

Canton opera was taking shape in the 17th century when the kunqu and an older form of the southern nanxi theatre (Yiyang qiang, I-yang ch’iang) merged together, while some of the melodies were adapted from Cantonese folk music. A crucial impetus was received when an actor exiled from Peking, called Zhang Wu (Chang Wu), founded a guild for actors near Canton. It is still regarded as a kind of shrine of the Canton opera. Canton opera was further enriched by a musical style called pihuang.

- Canton opera performed on a modern stage. Jukka O. Miettinen

By the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1944) the Canton opera, a style of a cosmopolitan commercial centre, received even more external influences. New plays were written and the costuming was partly modernised. One reason for these many innovations may be the fact that, in a big, international city like Canton, opera was forced to struggle for its survival with new forms of entertainment, including movies. In this competition Canton opera’s strategy was to assimilate the new trends. New stories, both Chinese and western, were adapted to the opera stage. Realistic stage sets, lighting effects and modern costumes were common, and the orchestra was expanded with western instruments, such as violins, guitars and even saxophones.

- Canton opera performed on a modern stage. Jukka O. Miettinen

Canton is the city in China that had the earliest contacts with the western world. It was also the place from where many Chinese immigrants moved to other parts of the world, to Hong Kong, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, and Thailand. Thus it is no wonder that Canton was also greatly influenced from outside China. According to one estimation, some one thousand new Canton operas were created during the early 20th century. Their stories were based on older plays, traditional Chinese literature, western literature, and on movies, both Chinese and western.

Chuan Opera, the Style of Sichuan

The origins of the Sichuan Opera or Chuan Opera (Chuanju, Ch’uan-chü) can be traced to a Ming-period (1368–1644) combination of two different traditions. They were the Ming-period yiyang and the local musical tradition. Later, the pihuang musical system was also added to this style, which evolved into an independent opera style at the beginning of the 20th century.

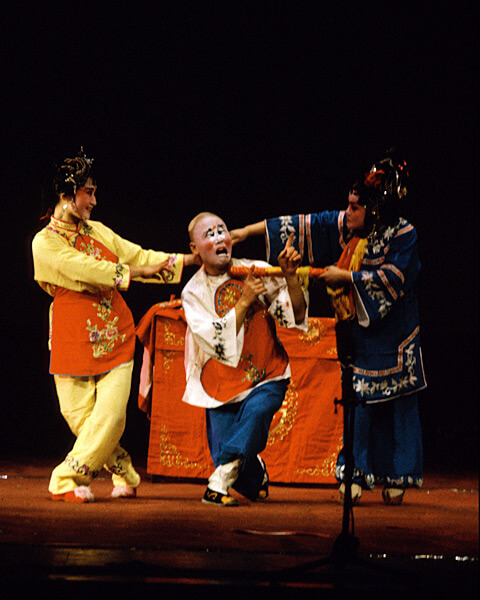

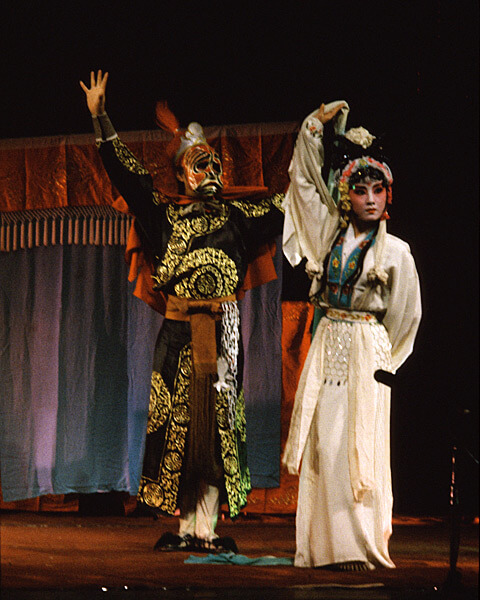

- Regional opera style of Sichuan is specialised in ghost stories and comic scenes. Jukka O. Miettinen

- Regional opera style of Sichuan is specialised in ghost stories and comic scenes. Jukka O. Miettinen

- Regional opera style of Sichuan is specialised in ghost stories and comic scenes. Jukka O. Miettinen

What is exceptional in the history of Chinese opera is that even at the beginning of the 20th century, when actors in China were regarded as low-class citizens, the training of the chuan actors also included general education and, furthermore, physical punishment of the students was forbidden. These early attitudes may be reflected even today in the sophisticated artistry of chuan acting.

The vocal technique of chuan opera sounds more natural, compared, for example, with the singing in Peking Opera. The acting style is also less stylised. The role of the painted face characters is different than it is in Peking Opera and only a few, if any, acrobatic fighting scenes are included in the chuan operas.

- Regional opera style of Sichuan is specialised in ghost stories and comic scenes. Jukka O. Miettinen

- Regional opera style of Sichuan is specialised in ghost stories and comic scenes. Jukka O. Miettinen

A unique speciality of the chuan opera is the use of thin silken masks, which can be changed in front of the audience in the blink of an eye with the aid of hidden threads and strings. When several layers of such masks are used one on top of the other, the actor can change his face and identity just by turning his head. The effect is indeed magical. This technique is often employed in the ghost operas, so popular in the chuan tradition. How exactly this intricate mask technique functions is still a well-guarded secret of the chuan professionals today.

Nuo Opera

The old forms of shamanistic mask theatre performed in remote villages and rural areas compose their own archaic group among the styles of Chinese opera. One of them is called nuo opera (Nuoxi, No-hsi). It is still performed in faraway villages in the province of Anhui. During the Chinese New Year celebrations the villagers take their robust masks out of the trunks and perform mask plays in order to drive away evil spirits. Nuo performances combine singing, dialogue, dance, and a simple musical accompaniment.