Chinese Theatre and Dance in the 20th Century

The gradual decline of the Qing Dynasty led to a long period of political unrest and turmoil. During the period of the Republic of China (1912–1949) traditional forms of Chinese theatre were still performed throughout the huge country. International contacts, particularly with the West, led, however, to new kinds of experiments and innovations in the big metropolises. They include, as discussed in connection with the period’s leading actor Mei Lanfang, modernised Peking operas, as well as completely new kinds of forms, such as the spoken drama or huaju and the song drama or geju.

Spoken Drama and Song Drama

Video clip: Current storytelling tradition from Tianjin, China Veli Rosenberg

As in most of the Asian cultures, no tradition of spoken drama existed in China either, prior to the era of the arrival of Western influence at the end of the 19th and at the beginning of the 20th centuries. In fact, the first production of Chinese spoken drama or huaju (hua-chü) was not even created in China, but in Japan, where the interest in Western theatre bloomed slightly earlier than in China. In spring 1907 young Chinese studying in Tokyo performed the third act of La Dame Aux Camélias by Alexander Dumas fils. The positive feedback the production received in Japan encouraged the student group, called The Spring Willow Society, to further stage Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher. It was the beginning of the tradition of Chinese spoken drama, which also quickly spread to Shanghai.

It is no wonder that Chinese spoken drama was born among young students and in Japan. Chinese society was in a chaotic state, because the imperial administration was unable to renew itself to respond to the Western commercial and political pressure which had transformed China into a kind of semi-colony. Chinese students were looking for solutions to the problems of their own society from the Japanese reform movement, while, at the same time, they absorbed elements from the Western ideologies and culture.

In Shanghai there had already been earlier spoken drama performances by Western amateur groups and the Western colonial community had built there a Western-type theatre house as early as 1866. Thus it was in Shanghai that the theatre house with a proscenium stage first became popular. The first Western-type theatre house, built by the Chinese themselves, was the New Shanghai Stage, which was opened in 1908. It had a semi-circular stage in which decors and new lighting technologies were employed.

The new spoken drama in Shanghai was propagated from 1919 onwards by a group of young activists, many of whom had studied abroad, called the May the Fourth Movement. Popular among this circle of intellectuals were plays by Western, mainly realistic, dramatists such as Björnson, Strindberg, Ibsen and Chekhov. New plays were also written, often designed to illustrate one central theme, such as, for example, the oppression of women in China. The themes mainly covered social and political issues instilling patriotism and, during the War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945), resistance to the Japanese occupation.

The audiences of huaju or spoken drama were mainly limited to the educated intellectuals who already shared a common world-view and political ideology. A debate was going on as to whether spoken drama should completely replace the traditional forms of Chinese theatre. Gradually, however, it was agreed that these two traditions could well live side by side.

This also led to new experiments in the field of music theatre. New plays with contemporary costumes were performed as geju song dramas. They employed melodies and conventions from, for example, the Peking Opera, the Canton Opera and the Sichuan Opera. As mentioned already before, Mei Lanfang also made his experiments in the field of geju. Similarly as in the spoken dramas, the themes of geju were also set in the present, often with anti-feudal, anti-imperialist and patriotic content.

Spoken drama abandoned the stylised and symbolical theatricalism of traditional Chinese drama forms. Instead, the acting technique was often based on Stanislavsky’s method, in which the actors should try to express psycho-realistically the “inner truth” of the individuals portrayed. The spoken drama tradition, which has been popular mainly in cities and among the educated elite, has been vital throughout the decades, and important dramatists have worked in this field.

In the beginning, huaju plays had only one act, but gradually they came to include several acts. This process is apparent in the works of the well-known dramatist, Tian Han (T’ien Han) (1898–1968). He started with one-act plays but later his plays grew in length. One famous play is his three-act tragedy Death of a Famous Actor, which he wrote at the end of the 1920s. He also worked in the field of modern Peking Opera. In his libretto, Guan Hanqin, he portrays the life of a famous Yuan-dynasty dramatist. The story is set in a brothel milieu in which the dramatist rebels against Mongol rulers and the imperial bureaucracy. Tian Han himself was also a brave critic of social injustice, which led to his disgrace and imprisonment during the Cultural Revolution. During the early years of the People’s Republic, however, he acted as the chairman of the Union of Chinese Dramatists.

Hong Sheng (Hung Seng) (1894–1955) wrote a trilogy set in an agrarian context. It includes Wukui Bridge (1939), The Smell of Rice (1931), and The Pond of the Black Dragon (1932). In 1948 Guo Moruo (Kuo Mojo) (1892–1978), who was also a renowned historian, wrote a play called Qu Yuan (Ch’ü Yüan). It tells about the prime minister of an ancient state, who commits suicide by drowning himself.

- The tradition of spoken theatre started to evolve in China at the beginning of the 20th century. Here a scene from Lao Shen’s Teahouse. It had its premiere in 1957. This performance was staged in the 1980s. The Archives of Finland–China Society

Maybe the most important Chinese dramatist who wrote for huaju is Cao Yu (Ts’ao Yü) (1910–). His best-known plays include the tragedy Thunderstorm (1933), which tells about the hardships of an authoritarian upper-class family, Sunset (1935), which is set in a brothel milieu, and Desert (1937), which was set in the countryside. Like Tian Han, Cao Yu was also persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, after which he acted as the chairman of the Chinese Theatre Union. One of the most popular plays in the huaju repertory is Teahouse (1957) by Lao She (1899–1966). This almost epic play is set in a teahouse in old Peking. It portrays the life of seventy individuals and covers half a century of their lives during the final period of the Qing Dynasty.

Theatre and the Early Communist Party

Leftist ideologies were common among intellectuals in the 1920s and 1930s. Even from its rise in the early 1920s the Communist Party of China realised the value of theatre as a weapon for social change. Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung) set the guidelines for the Communist theatre and proclaimed complete party control over the arts, a policy which reached its nightmarish culmination during the Cultural Revolution in 1966–1976.

Folk arts were revised to propagate revolutionary ideas. Some of their traditional features were maintained but much was modernised. Traditional opera styles, such as Peking Opera as well the clapper opera and other regional forms, were used as a basis for new dramas on contemporary themes and often aimed as propaganda against the Japanese.

New Peking operas were created. An acclaimed example is Forced Up Mountain Liang, Bishang Liangshan (Pi-shang Liang-shan), which was based on a historical epic, Outlaws of the Marsh, Shuihu zhuan (Shui-hu chuan). Although it portrayed events in the distant past, it acutely propagated rebellion against the feudal system. It had its premiere in 1945.

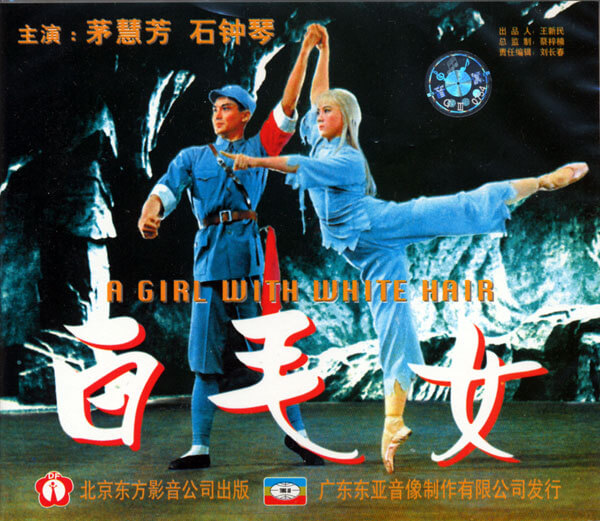

- A scene from the revolutionary model ballet, The White-Haired Girl. The Archives of Finland–China Society

In the same year a new geju or song drama, The White-Haired Girl, Baimao nü (Pai-mao nü) was performed for the first time. Its music was based on traditional folk melodies and it was accompanied by an orchestra which combined Chinese and Western instruments, while its costuming and décor aimed at realism. It was a great success and it was later revised and finally transformed into a revolutionary model ballet.

Theatre and Dance in the Early People’s Republic

The early phase of the People’s Republic, starting from its establishment in 1949, was an active time for the arts, as they were employed in the construction of the new society. The social status of theatre workers greatly improved, as they had their undeniable role in the class struggle and were no longer regarded merely as prostitutes. The policies that Mao Zedong had formulated earlier became the guidelines for all the arts, and also for the theatre, which was particularly appreciated for its educative value.

Regional theatre forms were reformed, and modern forms, such as huaju or spoken drama and geju or song drama were encouraged, of course, but only if they followed the strict official guidelines. A completely new form of art was created, the full-scale wuju or dance drama, which clearly reflected the close cultural ties between the People’s Republic and the Soviet Union.

Committees were set up and festivals held in order to define the exact role of theatre and dance in the new society. In 1950 the Ministry of Culture established the Traditional Music Drama Committee to plan a drama reform. It was agreed that even the traditional forms of theatre should be reformed so that they promoted patriotism and served Communist ideology and revolutionary heroism.

In the same year the First Nationwide Spoken Drama Festival made the Soviet influence apparent. Many productions reflected the psycho-realistic acting style, while realistic costumes and sets became the norm. Spoken drama was regarded as a suitable medium with which to portray modern life with its continuous class struggle. In 1952 the First National Music Drama Festival gathered together some 1800 performers from all over the country.

In his speech in 1956 Mao Zedong launched the famous slogan: “Let a hundred flowers blossom, and a hundred schools of thought contend.” The following so-called “Hundred Flowers Period” was a rather liberal time. In the same year that Mao delivered his speech, the Kun Opera was revived in the famous production of Fifteen Strings of Cash attended by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai. Next year Lao She’s spoken drama Teahouse, already discussed above, had its premiere. Many music dramas and other spoken dramas were also created.

The year 1957 also saw the premiere of the first Chinese large-scale dance drama, The Precious Lotus Lamp. It reflects many Western, mainly Soviet, influences. In movement vocabulary the ballet aesthetics were combined with national elements and flavour and pas de deux duos between the male and female leads were created in a similar way as in the Western ballet which was now also being taught in China.

Prior to 1963 the official policy was to combine the modern and the traditional and to rewrite traditional works to reflect patriotism and Marxist ideology. Political censorship grew stricter, however, and after 1963 attitudes rapidly changed. Due to the power game manipulated by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing (Chiang Ch’ing), herself a former actress, all traditional forms of theatre were gradually banned. The new guidelines for theatre were announced at a festival of modern opera in Peking in 1964. Thereafter, only operas with modern themes were favoured.