Dance and Theatre in the Civilization of Angkor

Indian influence started to spread to the region at the latest during the early centuries AD, when two kingdoms or chains of chiefdoms, Funan (c. 150–550) and Chenla (c. 550–800), flourished in the Mekong Delta area. The Khmer empire of ancient Cambodia flourished from the 9th to the 15th centuries. Even from the beginning of the period of its glory, state centralism was concentrated in the region of Angkor, near the Tonle Sap or Great Lake.

The civilisation of Angkor had its origins in the prehistoric Iron Age. Angkor, the then capital, bears marks of long-lasting constant urban renewal. It controlled the provinces through a network of shrines, both state and family temples.

The predominant religion was Brahmanism, most often in its Shivaistic form. Vishnuism, as well as forms of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, was also practised for shorter periods. One of the features of the syncretistic belief system was the elevation of the king to the realm of the gods. The conception of devaraja, which translates as “god-king”, is mentioned in the stone inscriptions that survive.

The Beginning of Greatness

Traditionally, the history of Angkor begins in the 9th century, when King Jayavarman II (790–835) declared himself a devaraja or a god-king, after, as stated in an inscription, he returned from “Java”. The term “Java” has often been interpreted as referring to the distant island of Java, but another solution has recently been suggested. It is possible that the place of his stay was the Champa kingdom nearby, in the coastal area of present-day Vietnam.

Jayavarman II established his capital first near the present-day Roluos, and later in the Kulen Mountains, both in the vicinity of Angkor. From this period onward the Khmer kings started to construct state temples. The form of a temple was initially a raised pyramid, a kind of artificial mountain, on which a linga, the phallic symbol of Shiva’s creative power, was placed. The king identified himself with Shiva and thus the linga became the focal point of the whole state. As was customary in India and Southeast Asia in general, the Khmer temples also represent Mount Meru in their symbolism, thus reflecting the ideas of Indian cosmology.

The temples housed statues of the deified king and his ancestors, whose names were combined with the names of Hindu gods. The state temples developed from simple stepped pyramids to more complex structures, finally combining all the architectural elements known by the Khmers. The culmination of the architecture of the state temples is the 12th century Angkor Wat, with its approximately 600 metres of narrative reliefs and nearly 2000 female figures, most of them dancing.

Textual Sources

There exist thousands of dance-related sculptures and reliefs from the Angkor period. Together with stone inscriptions they give us information about dance and theatre in the Khmer civilization. They, at least, make clear how important an element dance was in the Khmer culture, especially in temple rituals.

In his study of the civilization of Angkor, Charles Higham (2001) has referred to dance-related inscriptions starting from the period of the early kingdom of Chenla, which existed from the 6th to the 9th centuries until civilization reached its apogee during the rule of Jayavarman VII (1181–1220). An early Chenla inscription mentions a rather modest number of 17 dancers among gifts given to a temple. However, it is notable that even during the Chenla period the existence of male dancers is referred to.

It seems that, following Indian practice, employing girls as temple dancers was regarded as a form of merit-gaining in Khmer society. By the time of the rule of Jayavarman VII the dance groups had grown in size. Inscriptions mention, among other employees of the temple of Ta Phrom, 615 female dancers and 1000 dancers in the temple complex of Preah Khan. When the king’s son listed his father’s achievements in an inscription, he mentioned no less than 1622 female dancers. The inscriptions give valuable information about the social status of dancers. According to them it seems that dancers came from all levels of society.

Dancing “Apsaras”

- Dancing female figures, usually referred to as apsaras, Angkor Wat, 12th century Jukka O. Miettinen

The sculptures and reliefs give several kinds of information about Khmer dance. The most common images are those of the hundreds of figures of dancing girls, which are either shown dancing alone, in a group of two or three, or in a row formation. Traditionally these figures are automatically labelled “apsaras”, the mythical heavenly dancers of Hindu-Buddhist mythology.

Their turned-out leg position with its many variations is the most dominant Indian-influenced feature in the dance images in Southeast Asia from approximately the 8th century onward. In Khmer dance images, however, both the supporting and the raised leg are strongly bent, which often results in an exceptionally low position.

- Dancers and musicians in a wooden pavilion or palace, Bayon 13th century Jukka O. Miettinen

Most of the dancing “apsaras” convey an impression of dynamic movement, since keeping one’s balance in this position for a longer time seems nearly impossible. The torso is often stiff and erect, sometimes slightly sideways bent. The most dominant movements are those of the arms and hands. In fact, most of the elements of body and hand movements can be analysed according to the Sanskrit terms established in the Natyashastra.

- Military procession with a dancing drummer and other musicians, Bayon 13th century Jukka O. Miettinen

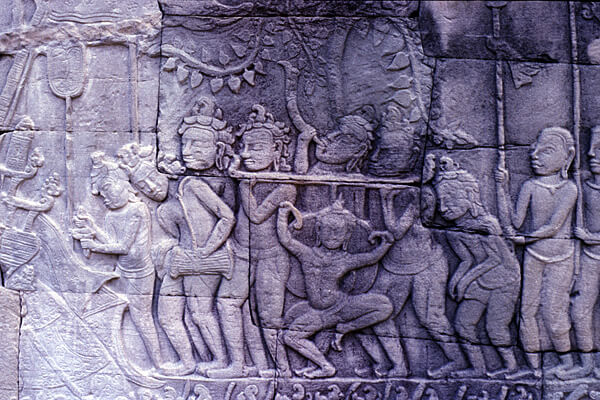

- Mock combat or training of martial arts, Bayon 13th century Jukka O. Miettinen

- Relaxed social dancing, possibly in an inn, Bayon 13th century Jukka O. Miettinen

- Procession and, below, a war dance, Bayon 13th century Jukka O. Miettinen

However, there does not seem to be direct Indian influence any more. The lowness of the position gives the movement an unmistakable “Khmer” flavour. Above all, the strongly backward-bent fingers, which are still a common feature in Southeast Asian dance today, regularly appear among the otherwise often Indian-influenced Khmer hand movements.

Besides these female dancers the Khmer dance imagery includes hundreds of portrayals of other kinds of dances too, such as processional war dances, training of martial arts, relaxed social dancing, and even acrobatic circus entertainment.

Epic Reliefs

A wide range of dance-related poses can be found in the narrative relief panels of Angkor Wat. As many of the myths portrayed in these narrative panels culminate in great battle scenes, the reliefs consequently show figures in several types of positions related to fighting. They include not only the above-mentioned flexed open-leg position but also poses related to the use of weaponry, especially to archery.

Although these positions are clearly also localised in Khmer reliefs, many of them, however, stem from the Indian tradition, where several fixed positions indicating the use of archery were categorised. The narrative reliefs often also depict stylised sitting and riding poses, which can still be seen employed in classical dance-dramas, both in Cambodia and neighbouring Thailand.

- Section of a large relief depicting the Hindu creation myth of Churning the Milky Ocean Angkor Wat 12th century Jukka O. Miettinen

One crucial question is whether some of the scenes shown in the narrative panels, such as the depiction of the Hindu creation myth, The Churning of the Milky Ocean, could have been based on actual theatrical performances. In the case of The Churning of the Milky Ocean this seems possible, as some scholars have suggested. This is supported by the fact that at least at the court of Pagan, as was already mentioned, and at the Thai courts of Ayutthaya and Bangkok as well as in East Java, the Indraphisekha ritual “pantomime” enacting the myth of The Churning of the Milky Ocean was regularly performed during the coronation ceremonies.

If this assumption were correct, the fact that large-scale mythological dance dramas were performed by male actor-dancers would explain the contradiction between the Khmer inscriptions and the imagery, which only rarely shows any male dancers. The hypothesis favoured by this author is that male dancers participated in large-scale dance dramas, such as the Indraphisheka.

This is supported by the fact that at the Thai courts of Ayuthhaya and Bangkok, the inheritors of the Khmer legacy, the large-scale dance drama, khon, enacting scenes from the localised Ramayana, was originally performed by male dancer-actors only. Indeed, when one compares the dance-related information provided by the reliefs of Angkor with still living dance traditions, it is exactly the Thai khon and its sister form, the lakhon kol of Cambodia, that one should look examine.