Dance in the Visual Arts

Besides the early literature, the visual arts, such as early sculptures, reliefs, and later paintings, also give extremely valuable information about theatre and dance. In India the whole phenomenon of the interrelation of dance and the visual arts, and indeed of other art forms as well, is a most crucial one.

The question is not merely of borrowing and exchanging materials and ideas from one art form to another. In Indian thought, dance, and all art, is basically a religious sacrifice (yajna). Art is also regarded as a form of yoga and a discipline (sadhana). Through the creation of a work of art the artist/craftsman strives to evoke a state of pure joy or bliss (ananda).

The human body was seen as a vehicle of worship and thus performances become acts of invoking the divine. By 200 AD at the latest, as stated above, the complicated techniques of dance-like acting, as well as the rasa system, were codified in the Natyashastra.

It is significant that in the Indian tradition it is dance, a temporal and corporal form of art, which is regarded as the ascendant art form. It set the measure for other forms of art, since they adopted the theory rasa from the tradition of the Natyashastra.

Dance and Sculpture

Dance has been so predominant in its position that some textual sources stress that sculptors and painters cannot succeed in their work without a basic knowledge of it. The Natyashastra sets the physical and dramatic tools for evoking the rasa or the emotional state appropriate to worship. On the other hand, the Silpashastras, manuals of iconography and sculpture, were intended to help in producing the corresponding figurative representations.

Consequently, the principles of movement, however complicated they may be, are the same for both a dancer and a sculptor. The final goal of this intricate science of movements, measurements, poses, gestures etc. is to create the rasa, the actual object of presentation and, finally, to reach even further in evoking the state in which transcendental bliss can be experienced.

All the three Indian religions, Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, share the same theoretical basis for dance and the visual arts. And so most of the margi or “classical” dance techniques, in spite of their local stylistic variations, bear strong similarities in all of these three traditions. Consequently, their imagery shares common aesthetic norms and iconographic features.

Dancing Gods

As early as from the Vedic period (1600–550 BC) onwards, Indian literature and mythological narrative created characters which were depicted in the visual arts as dancing or in easily recognisable dance-derived poses, reflecting the prevalent dance techniques.

During the classical Gupta age from the fourth to the sixth century AD the repertoire of the dance images expanded further, while the Puranas or mythological stories of the early centuries AD provided more dance-related imagery. Along with dancing human beings and semi-gods of older periods appeared dancing gods, the first of them being the dancing Shiva.

Shiva Nataraja, Shiva as the King of Dance

- Shiva Nataraja, Chola Dynasty 11th century AD, Thanjavur Art Gallery Jukka O. Miettinen

- A composite photo showing two poses indicating the dancing Shiva Sakari Viika

The sculpture-type called Shiva Nataraja can be regarded as one of the trademarks of Indian art. The iconography of the Shiva Nataraja, literally meaning the King of Dance, developed over the centuries and reached its crystallised form in Tamil Nadu during the Chola period in approximately the 10th–12th centuries AD. It was the very period when the art of bronze casting reached its apogee. The Chola sculptors were able to reproduce, in metal, the exact proportions laid down by the Silpashastras and even the tiniest details of the gestures and movements dictated by the Natyashastra.

The Shiva Nataraja represents Shiva as the destroyer/creator as described by devotional poetry dedicated to him. In the Hindu cyclical view of time Shiva’s role is to destroy one era in order to create the next one, and this is what Shiva Nataraja statues portray. When he executes his cosmic tandava dance of destruction and creation he is surrounded by an arch of glory fringed by flames.

The flame that he is holding in his upper left hand hints at the aspect of destruction, while the drum, symbol of the pulse of life, which Shiva holds in his upper right hand, refers to the aspect of creation. The lower left hand points to his lifted foot, while the lower right hand is shown in pataka mudra. Multi-handedness, a feature typical of many nrttamurtis, is a practical way to manifest the deity’s different aspects simultaneously. It also enables the sculptor to capture several frozen moments of a movement sequence in a static sculpture.

The main characteristic of Shiva’s dance in the Chola iconography is the uplifted leg. His right leg is firmly planted on a dwarfish creature, which personifies one of the six enemies of enlightenment. The sculpture is full of symbolism. Shiva’s braided hair is often decorated with his attributes: a laughing skull, a crescent moon and a cobra, and also often Ganga, the personification of the Ganges. The rasa, which Shiva’s dance always evokes, is raudra, the Furious.

Dance Images in Temples

- An early relief from Amaravati, in southern India, showing the open leg-position, which became common in dance both in India and in Southeast Asia, c. 100–200 AD, Chennai Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

Many of the early Buddhist reliefs with their dance-related images and the early dance images of Hindu cave temples are still in their original architectural contexts. The earliest surviving free-standing stone temples were built in the Gupta period. Gradually their plain outer walls were decorated with narrative panels as well as dancing divinities. This was the beginning of a development that was to lead to the flourishing of dance images in Hindu temple architecture during the so-called “medieval” period, approximately from the 7th to the 16th century.

- Temples in Khajuraho are covered with reliefs often showing dancers, 11th century Jukka O. Miettinen

- Dancers on a pillar of a temple in Mount Abu, West India, 12th century Jukka O. Miettinen

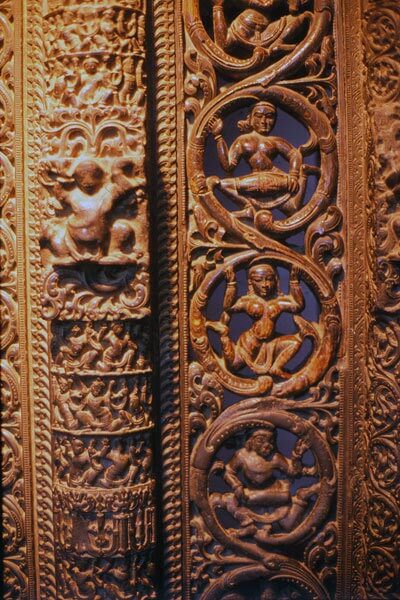

- A door frame with dancing figures in the position of flying, 12th–14th centuries, Chennai Museum Jukka O. Miettinen

The most abundant representations of dance images can be seen in the Hindu temples of South India, in the Bhubaneshwar temples in East India, and in the temples of Khajuraho in Central India. The West Indian Jain temples of Mt. Abu are also famous for their dance imagery. The styles of sculpture differ and local schools can easily be recognised, but the fundamental portrayal of the movement is mostly rooted in the tradition of the Natyashastra.

Dance Manuals in Stone

- Reliefs showing basic karanas or basic dance units at the Chidambaram temple in Tamil Nadu, c. 9th century Jukka O. Miettinen

- One the reliefs depicting karana dance poses at the Chidambaram temple Jukka O. Miettinen

Series of dance reliefs directly related to the Natyashastra can be found in some medieval temple complexes in South India. The most famous of them are those carved on the towering 9th century gateways of the Shiva temple in Chidambaram. They include ninety-three of the 108 karanas described in the Natyashastra.

These small relief panels, together with other similar series and contemporaneous murals depicting dancers, constitute an important source material when one is trying to reconstruct the karana movement cadences of the Natyashastra. What makes these Chidambaram karana reliefs so particular is that they are accompanied by inscriptions of Sanskrit verses from the Natyashastra. Thus they form a kind of an illustrated dance manual carved in stone.

Since the karanas have practically disappeared from the present Indian dance styles it is understandable that the academic study focusing on these reliefs has already had a long tradition. By means of these reliefs and their inscriptions scholars and dancers have tried to reconstruct the ancient karanas since the early 20th century.

Each panel shows one dancer in one frozen moment of a movement pattern. This led the early scholars to believe that karanas were actually static poses, an assumption which later research has renounced. The debate focusing on these panels has been very lively and has led to several attempts to reconstruct the karanas.