Kabuki, Theatre as Spectacle

- Kabuki combines mime, spoken drama, singing, music, dance, and stage tricks Sakari Viika

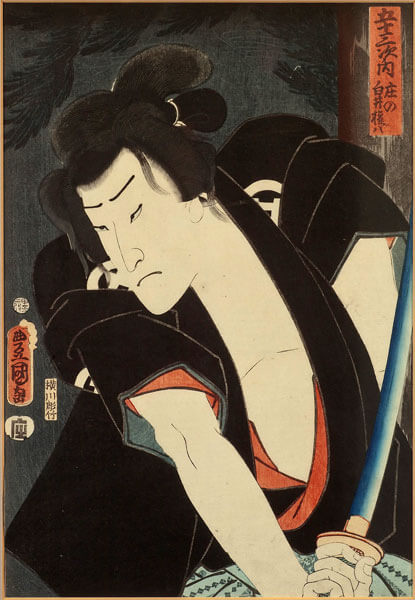

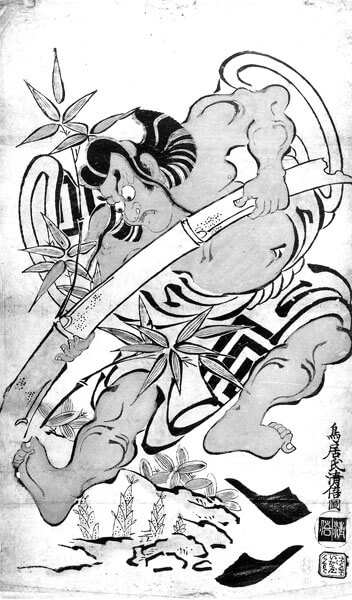

- A 19th-century woodblock print. No other Asian theatre form is visually as well documented as kabuki. Thousands of woodblock prints from kabuki’s golden age show famous actors in their celebrated roles, private collection Sakari Viika

No other traditional form of theatre in Asia has evolved into such a grandiose stage spectacle as the kabuki theatre, which is four centuries old. As its name, kabuki (song-dance-acting), indicates, it combines various genres of dance and music while it is characterised, at the same time, by its highly exaggerated, mimetic acting style.

Kabuki’s origins in sensational street performances and its later developments in the teahouse theatres of the notorious red light districts of the growing cities of the Edo period can still be traced in kabuki’s eroticism and its rich repertoire. Kabuki also adopted themes from its sister form, bunraku puppetry, as well as from the much older noh theatre.

During the golden age of kabuki, in the 18th and 19th centuries, the teahouse theatres grew in size, and complicated stage machinery with its revolving stage, lifts and several curtains was invented. Thus kabuki offers a colourful panorama of stage tricks, changing forms of scenery, and theatrical magic, rare in most forms of Asian theatre, which mainly focus on the actor’s art.

The History

If kabuki itself can be defined as “colourful”, the same, indeed, also applies to its history! The long process of the evolution of kabuki started on a river bank in Kyoto in 1603, when a group of female entertainers performed their variety show, led by a shrine maiden, Okuni. In fact, the institute of “shrine maidens” had, by then, partly degenerated into prostitution.

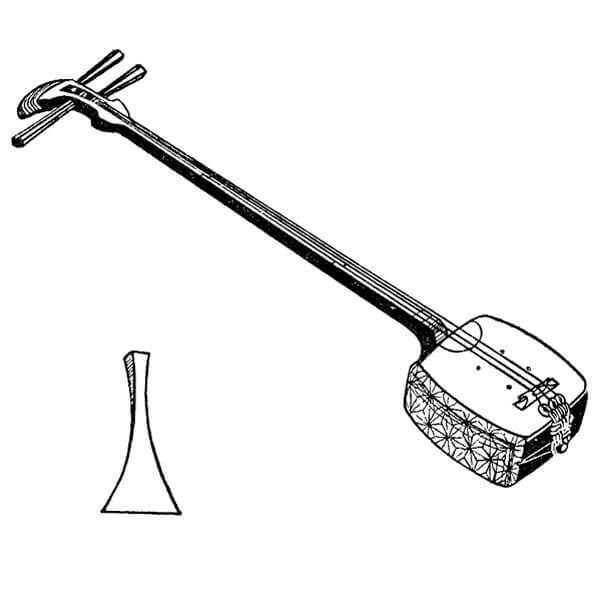

- A three-stringed shamisen lute Jukka O. Miettinen

The dances may have been based on earlier Buddhist shrine dances, while the music of this earliest variant of kabuki, actually onna kabuki (women’s kabuki), was derived from noh theatre. A new instrument, the three-stringed shamisen, the fashionable instrument of the period, however, gave it a new kind of attraction.

The short dance numbers and skits, performed by Okuni’s troupe, created a sensation because of their eroticism, their exotic costuming, which partly imitated the costumes of the Portuguese missionaries, and because of their cross-dressing scenes. The latter were, of course, not a complete novelty. In the much older noh theatre, for example, masked men played the female roles. What was new, however, was that women now appeared in male roles.

This first variant of kabuki was obviously connected to prostitution. So it was no wonder that the teahouse theatres of the red light districts soon adopted it too. Thus they could provide their customers with a new kind of entertainment while, at the same time, on the stage, they were able to advertise their merchandise, the girls.

Because of the great popularity of “women’s kabuki” and the uproar it created among male audiences, officials banned the onna kabuki in 1629. This led to the next variant of kabuki, that of wakashu kabuki or “young men’s kabuki”.

The teahouse brothels also offered the services of young men, rather popular in the bisexual atmosphere of the “pleasure quarters” and their particular life style called ukioyo or the “floating world”. When girls were banned from the stage, boy actors replaced them.

Boys with “sexy” forelocks (usually shaved at the boys’ coming-of-age ceremony) in particular gained popularity in the female roles, and they immediately got ardent male admirers. Once again, in 1652, officials had an excuse for censorship and they banned this form of kabuki, thus putting an end to the short period of “young men’s kabuki”.

Adult men, however, were not prohibited from performing on the stage, which led to a new and final variant of kabuki. It was yaro kabuki or the “male’s kabuki”, in which all roles, even the female ones, were played by grown-up male actors.

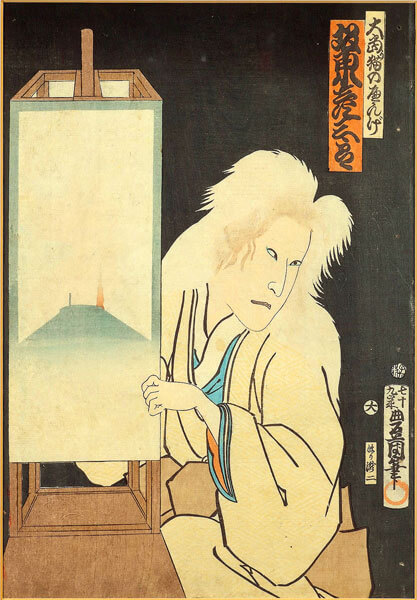

- The woodblock prints show famous kabuki actors in their stage costumes and make-up, private collection Sakari Viika

Kabuki distanced itself from prostitution and began to attract serious dramatists. Talented actors also contributed to its development by creating new types of role, such as the exaggerated onnagata or the female impersonator, wagoto, or the elegant male lead, and later aragoto, the powerful male lead. Each of them inspired new types of dramas.

Kabuki evolved into different branches. In the region of Kyoto and Osaka the inspiration for kabuki was provided by the erotic, hedonistic “floating world” or ukioyo of the “pleasure quarters” of the bigger cities. This life style, with its famous prostitutes and kabuki star actors, has been depicted in thousands of the coloured wood block prints of the period.

Another, more powerful and flamboyant style evolved in the first half of the 18th century in Edo, which was the seat of the military government. This aragoto style of acting was influenced by bunraku puppetry, discussed in the previous chapter.

Both bunraku and kabuki shared much of the same repertoire, such as the plays by Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) and many other prolific writers. The types of role and the style of bunraku puppetry influenced many conventions, acting technique, and the facial expression of kabuki.

The years at the end of the 18th century and most of the following century were the golden age of kabuki. Several innovative dramatists widened its repertoire by adding the categories of the jidaimono (history plays) and the sewamono (domestic plays), and several new categories, such as the ghost plays (kaidanmono), noh-based dance-dramas, and the thief plays (shiranamimono) to the two older categories discussed above.

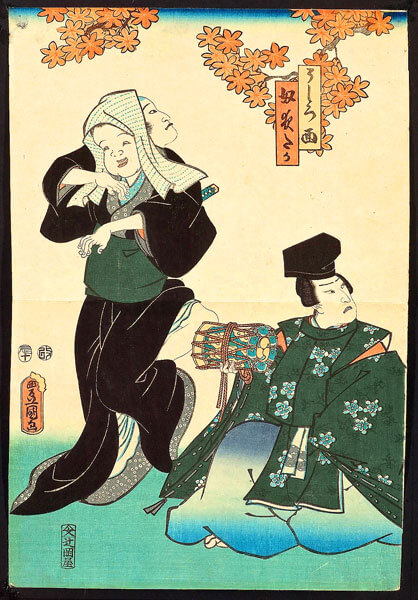

- A scene with onnagata female impersonators from a 19th-century kabuki performance, private collection Sakari Viika

Kabuki theatres grew from simple teahouse stages and later wooden structures, reminiscent of the noh stage, into actual theatre houses with increasingly complicated stage machinery. It became customary to construct a full-day kabuki performance on a double-bill basis, so that often a jidaimono play started the programme and a sewamono play ended it.

By the end of kabuki’s golden period, most of its various acting styles, with their respective repertoire, were established. Prolific actor families and lineages, who specialised in certain styles and plays, dominated the colourful world of kabuki, much as they still do today.

From all the four “classical” forms of Japanese theatre it was only kabuki that was able to maintain its full popularity during the Meiji period (1868–1912). Noh and kyogen became rarities, while the bunraku tradition was continued mainly in Osaka. Kabuki, however, adapted themes, texts, conventions, and dances etc. from these older traditions.

- The Kabuki-za Theatre in Tokyo is the centre of the kabuki world Jukka O. Miettinen

Tokyo (formerly Edo) became the centre of kabuki, and by the end of the 19th century there were three large kabuki theatres. All of them were destroyed by fires and bombings, and only one of them, the famous Kabuki-za, was rebuilt in 1952. Nowadays the National Theatre of Tokyo also serves as a stage for kabuki.

During the Meiji period, when Westernised forms of entertainment became fashionable, a new type of more realistic kabuki was introduced. It was shin kabuki or “new kabuki”, which never really gained wide popularity.

From the 20th century until the early 21st century kabuki has definitely remained the most popular form of traditional theatre in Japan. But it has not stagnated into being a kind of “museum piece”. Far from that, various, even contradictory, trends can be recognised at the moment. Several remarkable actor-producers have made innovations in order to modernise kabuki, while some other, similarly important artists are digging deeper into its roots. Kabuki was officially added to UNESCO list of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity in 2008.

Actors and their Types of Role

In only a very few theatrical traditions have the actors played such a crucial role in creating and formulating the contents of the whole art form as is the case in kabuki. In fact, most of kabuki’s types of role and their respective drama genres were invented by remarkable actors.

There are several role categories with their various sub-categories. Some actors may be so versatile that they can perform several role categories. Most often, however, an actor specialises in only one of the categories, as their acting techniques, use of voice etc. require almost life-long training and specialisation.

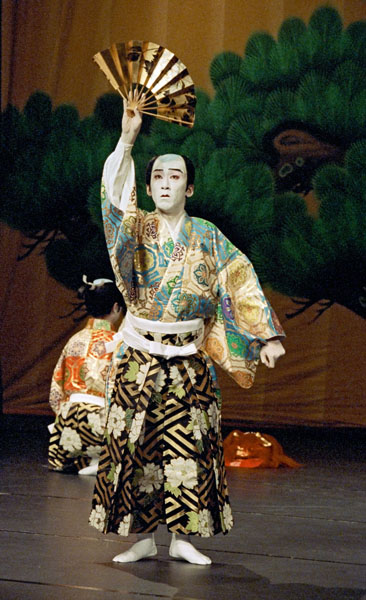

- Wagoto, the refined hero of kabuki Sakari Viika

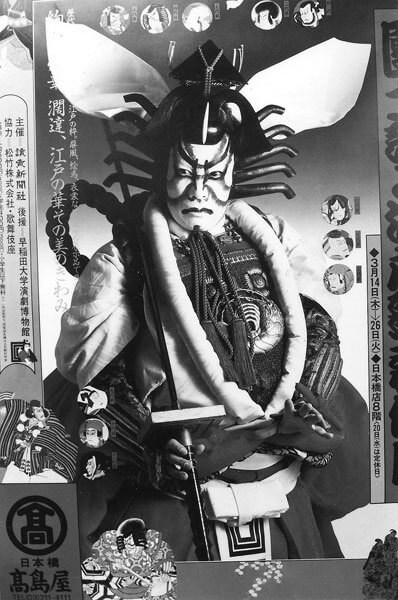

- Shibaraku, the famous aragoto character in the repertoire of the Ichikawa acting family, a kabuki poster Jukka O. Miettinen

- Danjuro I in the role of Goro, an early woodblock print Tsubouchi Memorial Museum, Waseda University

Wagoto is a young man about town, usually elegant, even effeminate, and most often in love with a famous courtesan. He may be a hero but he is often also a vain and even slightly comical character. This role category was the creation of the actor Sakata Torujo (1647–1709). Wagoto’s white make-up and costuming were based on the urban fashions of the Edo period.

Aragoto (wild warrior style) refers to strong, even aggressive male characters that may be good or evil. With their flashy, exaggerated acting technique, stylised make-up, heavy costuming and often with high shoes they are, both metaphorically and literally, “larger-than-life” characters.

This type of role was created by a famous actor from Edo, Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660–1704). The aragoto type of character became extremely popular and the actor lineage, founded by Danjuro I, still continues to maintain the tradition today.

Onnagata, the female impersonator, may be regarded as the epitome of the stylised, caricature-like acting technique of kabuki. The practice of having male actors in female roles has its roots in the early 17th-century wakashu kabuki or “young men’s kabuki”. When female actors were banned from the stage in 1629, young boys replaced them.

When boy actors were banned in 1652, adult men also took the female roles. An early important onnagata actor was Yoshizawa Ayame (1673–1729). He was a “transvestite” actor, as he also lived his off-stage life as a woman. Throughout kabuki’s history onnagata actors have been stars who have been particularly admired and have, for example, dictated women’s fashion.

Onnagata roles can be divided into numerous sub-categories, each with their own characteristics. Keisei is a flamboyant courtesan, akahime refers to the daughters of samurai warlords, akuba refers to the evil women of the sewamono plays, baba roles cover various old women, musume refers to the daughters of ordinary farmers or townsmen, etc.

Besides the three main role categories discussed above, wagoto, aragoto, and onnagata, each with their own sub-categories, there are several minor types of role. Katakiyaku, with its own various sub-categories, refers to villains, sabakiyaku types are good, righteous male characters, jitsugoto refers to characters based on historical personalities, while sanmaime types are comic male characters.

Actor Families and “Acting Houses”

As in noh, so too in kabuki an actor’s profession is, to a great extent, a hereditary one. It is passed on from father to son or from uncle to nephew. Sometimes, however, if there is no younger generation to continue the line, a talented student can also be “adopted” into the family.

This lineage system has created a complicated system of stage names. Particular stage names are reserved for certain families and they are given to the actors, when the time comes, in formal ceremonies, called kojo. For example, the stage name Danjuro belongs solely to the Ichikawa family. It is, without doubt, the most prestigious stage name in the whole kabuki tradition.

- Danjuro XII received his venerated stage name in a formal kojo ceremony in 1985 Kabuki-za

Danjuro I (1660–1704) was the creator of the strong aragoto type of role. The present Danjuro of the Ichikawa family got his stage name, Danjuro XII, in a formal kojo ceremony in 1985. Thus an actor may appear on the kabuki stage under different names during different periods of his life. Before he was proclaimed Ichikawa Danjuro XII, the actor was performing under the name Ichikawa Ebizo.

To make matters even more complicated, the actors also have an “acting house” name, called yago, in addition to their family names and stage names. All kabuki actors belong to one of the many “acting houses”. The “house” is indicated by crests or kinds of “logos”, which serve as emblems in their costuming and props.

Various Types of Plays

Kabuki plays are drawn from surprisingly many sources. Many of them are shared with the bunraku puppetry. Thus many famous plays can be seen both on the bunraku and kabuki stages. Two important categories of plays are adapted from the bunraku repertoire. They are jidaomono (history plays) and sewamono (domestic plays).

The jidaimono plays often refer to the great epics of the feudal period, such as The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari) and the Tales of Ise (Ise Monogatari). Thus they are set in the distant past. One reason for this was that the officials of the Edo period were very sensitive to any kind of criticism. So the playwright avoided censorship by setting his dramas in the distant past.

The gorgeous style of the costuming of the jidaimono plays reflects the fashions of the early feudal period. In the acting style they are highly stylised.

The sewamono plays, on the other hand, are more realistic in style, while their costuming is based on the practices of the Edo period. The first sewamono play was Chikamatsu Monzaemon’s (1653–1724) Sonesaki shinju (1703).

Like other sewamono plays, Sonesaki shinju recounts the lives of ordinary people of the Edo period, not about mythical heroes of the past. Many of the sewamono plays were based on true events. Those plays about double suicides committed by lovers (shinju) became so popular that they were banned from time to time.

- Dancing butterflies in the noh-derived dance play Kagami jishi or The Mirror Lion. Also the pine tree backdrop is adopted from noh Sakari Viika

The third major category of kabuki plays is the shosagoto plays, which concentrate on dancing rather than acting. In fact, dance forms an integral part of most of the kabuki plays, but in the shosagoto plays the dances, performed against beautiful backdrops, are the main content of the plays. Most of the kabuki plays, which were adapted from the noh repertoire during the Meiji period, belong to this category.

As mentioned in the chapter above, prolific actors created new role types with their respective repertoire. Sakata Torujo (1647–1709) was the innovator of the wagoto type, the soft and elegant townsman of the Edo period. Wagoto is the main character of many kabuki plays.

Ichikawa Danjuro I (1660–1704), inspired by a certain bunraku puppet type, developed the flashiest of all the kabuki male characters, aragoto, the powerful larger-than-life type, full of energy. It also demanded new plays in which aragoto would be the leading character.

- Danjuro XII as Sukeroku, one of the most popular aragoto characters Kabuki-za

- The actor Bando Mitsygoro as a Cat Ghost, mid-19th century woodblock print, private collection Sakari Viika

- A maiden is transformed into a furious male character, a 19th century woodblock print Sakari Viika

An illustrious member of the Ichikawa family, Danjuro VII, began the tradition of compiling collections of plays favoured by an actor lineage, in this case the Ichikawa family. His Eighteen Favourite Plays (1840) served as inspiration for several later collections compiled by other kabuki families.

Kabuki plays can also be categorised according to their themes. There exist, for example, plays based on the older noh and kyogen repertoire, which are called matsubamemono. Plays in which there is a vendetta are referred to as sogamono, plays involving lovers’ suicides are called shinjumono, ghost plays are referred to as kaidanmono, while plays dealing with the lives of famous thieves are called shiranamimono etc.

Hengemono or the “transformation pieces” is in a category of its own. They are often dance plays in which the main actor assumes several roles in succession. Mostly they involve supernatural beings such as various ghosts. Shin kabuki refers to the modern kabuki pieces of the Meiji period in which stage realism was favoured and from which many of kabuki’s special features and stage tricks were eliminated.

The Stage and its Machinery

During the 18th century, the kabuki stage developed into a complicated “magic box” with several types of curtain, lifts, traps, and even a double revolving stage.

In its complexity the kabuki stage can only be compared with the “baroque stage”, which evolved in Europe at approximately the same time. Both of them aimed to fulfil the various needs of the dramas that were performed on them. Both of them aimed to maximise the stage magic in order to amaze the audiences. There are, however, clear differences between the Western baroque stage and the kabuki stage.

The Baroque stage grew out of the European court theatre tradition, while the discovery of the “scientific perspective” during the Renaissance was crucial to its development. It led to the type of rather high and deep stage on which the illusions of far distances could be created by manipulating the vanishing point by means of illusory side- and backdrops.

Kabuki theatre, born in the “pleasure quarters”, on the other hand, has a very wide stage. The almost two-dimensional painted scenery reminds one of the traditional Japanese style of painting, while the wide, horizontal stage opening reminds the viewer of Japanese horizontal picture scrolls.

- Kabuki stage: 1. hanamichi pathway, 2. trap door for supernatural entrances and exits, 3. room for backstage geza musicians, 4. revolving stage with large traps

The earliest kabuki performances were performed on temporary stages. During kabuki’s early popularity it was performed on wooden structures, more or less similar to the noh stage. By the end of the 17th century the kabuki stage had adopted one of its characteristics, hanamichi or the “flower path”, a pathway which leads from the back of the auditorium to the left corner of the actual stage.

Important entrances and exists are made through hanamichi. This brings the actors to the middle of the audience. Important self-introductions are also performed on it and thus special acting techniques related to hanamichi evolved. The back room, at the back of the auditorium, into which the hanamichi pathway leads, is connected with the backstage area by means of a tunnel, called “hell”. Another pathway, kari hanamichi, may be erected on the other side of the auditorium when the play requires one.

Quick stage changes were made possible by the means of curtains (maku). The main curtain, striped joshiki maku, is opened from right to left. Other types of curtain are black (invisibility) and blue (heaven). Some of the curtains are dropped onto the floor while a rising curtain is often used in the dance plays.

In some cases the changes of set are not hidden from the audience. In fact, they may be the highlights of some plays. For example, during a fighting scene, taking place on a temple rooftop, the whole temple building is lowered by lifts into a huge trap so that the audience may have a better view of the action on the roof.

Complicated lift and trap systems, evolved through centuries, make it possible for the heavy sets to appear and disappear in the blink of an eye. In the same way, actors, particularly those in the fabulous surprise scenes, may suddenly appear in front of the audience from the most unexpected places.

The full-size revolving stage, which was used in Europe for the first time in 1896, had already been invented in the kabuki context in 1758. Soon a dual revolving stage was also introduced. It enabled still more complicated and quick stage changes as well as sensational illusions, such as sea scenes with several moving boats.

Illusions form an important element in many of the kabuki plays. One of the most fabulous stage tricks is “riding the heavens” (chunori) in which an actor flies over the stage, or even over the auditorium. Certain types of plays make full use of these stage tricks of the fully developed kabuki stage, while some others use them sparingly, if at all.

Actors’ Techniques and Training

The acting technique of kabuki is, to a great extent, based on imitation of the actions and behaviour of the people of Japan’s various historical periods. The life of the courts, samurais, and even ordinary townspeople were restricted and dictated by complex codes of behaviour, all of them reflected on the kabuki stage.

For example, the spoken language and the body language of men and women differed drastically (as they partly still do in Japan). Exaggeration, as in the art of the caricatures, is the key to kabuki’s mimetic acting technique (furi). Thus, for instance, the undulating onnagata characters with their tiny steps further exaggerate the already idealised conception of femininity of the Edo period.

The strong male characters, on the other hand, epitomise the macho masculinity that once dominated the world of the samurais so much. While onnagatas keep their feet closed and walk with small, troublesome steps, the vigorous aragoto male characters walk with powerful steps and sit with their legs wide open.

The striking characteristic of kabuki acting is its use of highly exaggerated facial expressions. It sharply differs from the expressionless “stone face” acting of the older court-related forms, such as bugaku and noh. In the kyogen farces, evolved directly from folk theatre, on the other hand, exaggerated facial expressions formed an important part of the acting technique.

- Dancing forms an integral part of the onnagata actors’ technique Sakari Viika

- Just like many other Asian dance forms, kabuki dances adapted movements from the martial arts Sakari Viika

All the above-mentioned aspects, the various codes of movement and the expressive facial technique represent kabuki’s mime aspect, furi. Just as important for kabuki acting is the art of dance, which falls into two categories, that of archaic mai (as, for example, in noh) and odori, a more free and rhythmic type of dance.

The Kabuki student already starts dance training in his childhood. He must familiarise himself with a vast repertoire of dances, particularly if he specialises in the onnagata roles. In most of the noh-derived kabuki plays it is dance that dominates. Even in the plays in which dance does not dominate, the exaggerated acting, with its fixed role categories and their specific techniques, approaches dancing very closely.

As kabuki is, to a great extent, a hereditary profession, its training is done within the acting families. The student may have separate classes in dance and in music, but otherwise an older master transmits whole roles and their minute interpretations to younger actors. Only an extremely experienced and venerated actor may dare to make slight changes in the interpretation, which has been maintained and cultivated by a family line that stretches back for generations.

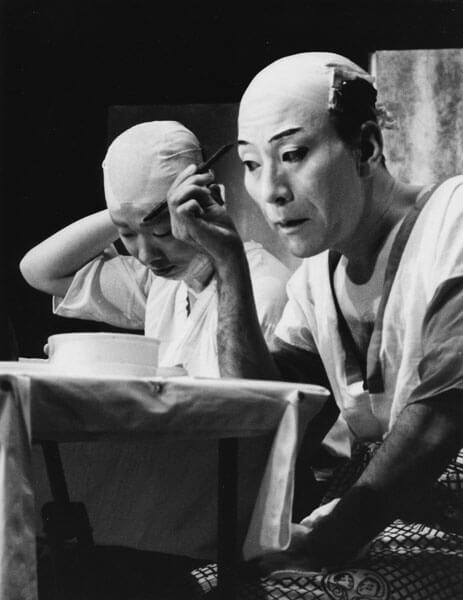

The Make-Up System

The most common make-up (kesho) of the main characters of kabuki is pure white. It is the colour of purity, refinement and aristocracy. Many of the commoners, such as servants and peasants, have more brownish make-up, indicating the tan of people who work outdoors.

- An onnagata actor applies his make-up Juhani Lompolo

The white make-up is done by first shaving or pasting the eyebrows, after which the white base is applied. (The onnagata characters have a red base under the white layer.) After that, the eyes are outlined with black and red, the lips painted and finally the eyebrows are marked high on the forehead.

This type of make-up makes it possible to exaggerate the facial features according to the general flashy aesthetics of kabuki. It also accentuates the facial expression, which dominates kabuki acting so much, and makes it clearly visible to the audience.

- The red kumadori make-up of a vigorous, yet righteous aragoto hero

There are also several, even more stylised, special types of make-up. The most exuberant of them is kumadori, a make-up style that evolved along with the aragoto, or vigorous male characters, invented by Ichikawa Danjuro I. In kumadori, make-up lines which exaggerate the actor’s facial features are painted on his face. Red lines indicate a good character while blue ones indicate an evil character.

The actor usually applies his own make-up. In some plays, particularly in the so-called “transformation plays” in which the actor quickly jumps from one role to another, several layers of make-up painted on thin cloth are used in order to change the actor’s appearance.

Costuming and its Handling

Costuming in kabuki is called isho. The kabuki repertoire covers numerous types of plays; some of them narrate the feudal intrigues of the past (jidaimono), some recount the everyday life of the Edo period (sewamono), and some depict ghosts and supernatural beings.

- Dance of a lion in the noh-derived dance play Kagami jish or The Mirror Lion. The gorgeous costuming is adapted from noh. The handling of the wig forms an integral element of the dance technique Sakari Viika

Thus kabuki also uses several types of costumes. The costumes of jidaimono plays resemble heavy dresses of old times, much like noh costumes. Men often wear wide, skirt-like trousers and they have wide, stiffened shoulder extensions.

The realistic costumes of the Edo period are used in the sewamono plays. The most modest of them are the “paper kimonos”, which indicate poverty, while the most splendid are the costumes of the popular courtesans. They consist of several layers of kimonos covered by a heavy outer robe. The lowered collar of the back of the kimono reveals the neck, which has been regarded as a most erotic detail.

- The glittering costume of an onnagata character Sakari Viika

The costumes may reveal many things and they convey hidden messages. Their colours and particularly their embroidered details, such as various flowers, may have symbolic meanings. By merely opening the hem of a kimono or revealing the sleeve of the lower kimono an actor may give secret messages. A long, highly erotic seduction scene, for example, can be enacted simply by provocatively opening different layers of costuming.

Thus the handling of the various types of dress forms an integral part of the acting technique. The costume changes are part of the show. There are two types of quick changes, done in full view of the audience. These special techniques evolved as tricks for the transformation pieces (hengemono) in which the main actor appears in several roles and thus the quick changes of costume, and often also the make-up, form the highlights of the play.

In some plays, particularly in the dance pieces, the koken or stage assistant, who is behind the dancing actor, pulls cords which hold the outer robe together to quickly reveal the lower garment. This kind of hikinuki quick change can be done when the actor jumps from one role to another. It can also be done just for its surprise effect or to change the atmosphere of the scene.

Bukkaeri indicates a kind of “half hikinuki” in which only the garment of an actor’s upper body is changed by the stage assistant. Both hikinuki and bukkaeri are examples of the various stage tricks and special techniques of kabuki, which are always loudly applauded by the audience.

Other Special Techniques

One of the most important special techniques of kabuki is mie, a dramatic movement sequence, which ends up in an expressive pose culminating in a highly stylised facial expression with crossed eyes. Mie is performed by male actors, while similar poses, although less stylised and without crossed eyes, of the onnagata female impersonators are called kimari.

They are the highlights of a play just as the highest notes of arias are in Western opera. These dramatic climaxes are anticipated by wooden clappers and by rhythmic shouts of encouragement (kakegoe) of the semi-professional kabuki fans in the auditorium. The mie poses and their caricature-like facial expression, always applauded by the audience, are like “logos” of the plays. They have been repeated in the old wooden block prints as well as in the modern kabuki posters.

Another special technique is roppo (six directions), a stylised, exaggerated way of walking typical of the vigorous male characters, which is often seen in the aragoto and jidaimono plays. The roppo, with its powerful arm movements and high steps, is mainly executed on the hanamichi pathway to signify the exit of an important character.

- A famous battle scene from the play Hiragana Seisuiki Kabuki-za

The fighting scenes in kabuki are called tachimawari. As in the Peking opera of China, so too in kabuki the battle scenes clearly reflect the techniques of the martial arts. However, in kabuki they are even more stylised than in the fast and highly acrobatic battles of Chinese opera.

In addition, various weapons and acrobatic somersaults etc. are used in kabuki’s tachimawari scenes, but the scenes are shown as in slow motion in order to let the audience clearly enjoy all their details. Usually the hero conquers his enemies with superior ease without even touching his opponents. With their intensive percussion accompaniment, the scenes are masterworks of group choreography.

Styles of Music

Kabuki uses a particular style of shamisen-accompanied narration (gidayu) as well as several types of music, which is divided into two main categories, those of the narrative katarimono and the more lyrical utaimono. The former evolved from the narration and music of bunraku puppetry, while the latter had its origins in types of music that accompanied various dances.

A third type of music, geza, is provided by musicians half hidden from the audience in a small room on the right of the stage. The dominant instrument of kabuki is the three-stringed shamisen lute. The off-stage geza orchestra, however, uses several other instruments in order to provide changing atmospheres and special sound effects, such as storms, rain etc.

In some plays, particularly in the dance plays derived from the noh repertoire, the orchestra and singers sit on platforms at the rear of the stage. However, it is not music alone that forms kabuki’s rich aural world.

Two types of wooden clappers are used for different purposes. Hand-held ki clappers, with their intensive crescendo, announce the beginning of the play, while the tsure clappers, struck against a board, anticipate and accompany dramatic climaxes, such as the dramatic mie poses. These highlights are also accompanied by the loud, well-timed kakegoe shouts of encouragement and appreciation from the semi-professional kabuki fans.