Kathak, The Indo-Persian Dance Style

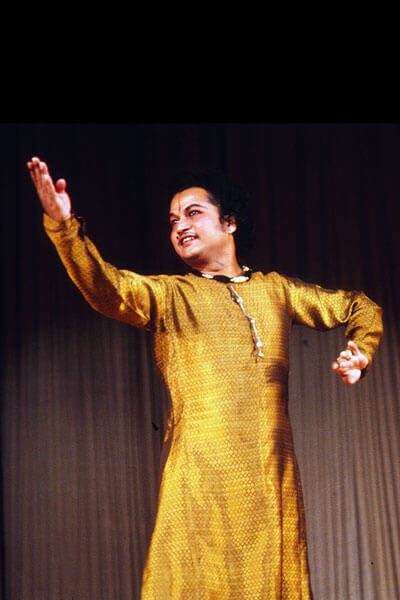

- Elegant arm and hand gestures of kathak Sakari Viika

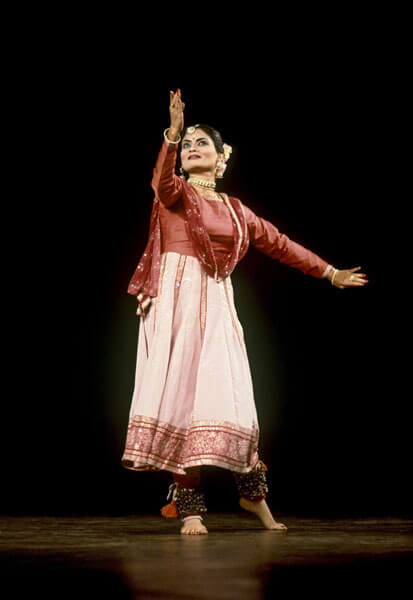

- Typical arm poses of kathak Sakari Viika

The present form of kathak dance is a fruit of the fusion of indigenous Indian tradition with Islamic culture in the northern parts of India during the golden age of the Moghul dynasty from the 16th century to the beginning of the 18th century.

Many of kathak’s elements, such as the poems depicting Hindu mythology and the division of the dances into pure nrtta and mimetic abhinaya sections, stem from an older local Hindu tradition. However, in its aesthetics as well as some of its technical aspects, characterised by linear poses and pirouettes, kathak clearly reflects the Islamic influences received, to a great extent, from Persia.

Its History

Sculptural evidence shows that prior to the arrival of Islam the northern parts of India also had their own lasya dance styles, more or less loosely connected to the tradition of the ancient Drama Manual, the Natyashastra. They lost their popularity, however, during the gradual islamilisation of northern India, a process that started as early as in the 9th century AD.

The roots of kathak seem to lie in the storytelling tradition of ancient northern India, practised by the nomadic storytellers called kathaks. They elaborated their narration with dance poses, gestures and facial expressions. Another source may be the temple dances performed by the northern devadasis.

Although Islam, in principle, has a negative attitude towards dance, the Islamic rulers were, however, admirers of many aspects of Indian culture. Thus the northern Indian storytelling tradition and dance were adapted according to the tastes of the rulers and minor nobility of the Moghul dynasty. Simultaneously, kathak was also practised in the smaller Hindu courts of Rajasthan.

Kathak’s poems, enacted by the abhinaya technique, still depict episodes from Hindu mythology in a pure bhakti spirit. In fact, kathak developed side by side with raslilas, the northern Indian pilgrimage plays dedicated to Lord Krishna. Both genres were deeply influenced by the Vishnu bhakti movement. Raslila adopted kathak as its dance technique, while kathak borrowed the Krishna-bhakti themes from raslila.

In the Mughal court context, with its non-Hindu audience, kathak, however, lost its direct religious meaning. Instead of devotion, the new audiences valued virtuosity, which is still a dominating characteristic of kathak today.

- An 18th century miniature painting showing a duo pirouette, Indian Museum, Calcutta Jukka O. Miettinen

Northern Indian miniature paintings (book illustrations) serve as an important source for throwing light on the later evolution of kathak. The paintings clearly show, for example, the development of the kathak costume as well as various combinations of instruments used to accompany it.

Gradually, particular kathak schools or gharanas evolved in northern India. The most important ones are the schools of Jaipur, Lucknow, and Benares with their slightly different styles and emphases. The period of British colonial rule sent kathak into decline. Kathak was still practised in its original courtly context, but the British regarded it as low entertainment and gave it an unwholesome image by calling it nautch dance, more or less meaning “prostitute’s dance”.

Since the mid-20th century kathak has undergone a phenomenal process of revival. The Maharaj family of dancers gave the dance new impetus and also expanded its repertoire to include duos, trios and group works. As has always been the case, kathak is today practised by both female and male dancers. It is now regarded as one of the “classical” forms of Indian dance, while it is studied and performed over the whole of India as well as in Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Western world.

The Music and the Poetry

In a similar way as the solo dance forms described above, so, too, has kathak evolved in an intimate interrelationship with the classical music tradition of the region of its birth. While bharatanatyam, kuchipudi, and partly also mohiniattam, are accompanied by the classical southern Indian Carnatic music, the accompaniment of kathak belongs to the northern, Hindustani school of music.

The small orchestra accompanying kathak usually consists nowadays of four or five musicians including two percussionists, one of whom plays the tabla, a vocalist, and one or two musicians playing stringed instruments, such as sitar, sarod or sarangi. A small, Western-influenced harmonium may also be included.

The music employs the Hindustani raga system, and many of the basic forms of Hindustani music are adapted for the kathak repertoire. The classical Hindustani music genres used in kathak include, among others, thumri, dhrupad and ghazal.

- The dialogue in kathak between the dancer and the tabla drummer is of the utmost importance Sakari Viika

The relationship of the partly improvised music and dance is a close one indeed. The seamless co-operation of the tabla player and the dancer is of the utmost importance. Many of the compositions include bols, or rhythmic words or rather syllables, marking the rhythmic pattern and partly helping the dancer to memorise the tala or the rhythmic time cycle. Often the dancer himself or herself sings these syllables.

The pure nrtta sections of kathak are characterised by extremely intricate rhythmic patterns. Often the tabla player and the dancer have a kind of competition in which the drummer first performs a rhythmic pattern, which the dancer then immediately repeats and elaborates while the drummer again reiterates the dancer’s version and again provides a new and even more intricate pattern.

In these rhythmic elaborations, or “plays” with the time cycle, the borderline between dance and music disappears and kathak, in fact, approaches pure mathematics. The virtuosic quality of kathak depends a great deal on the handling of the rhythm, which is intensely observed, and even loudly counted, by the spectators, who are connoisseurs.

In the abhinaya sections, lyrical, even devotional, forms of Hindustani music are employed, such as thumri and ghazal. The texts sung by the singer and enacted by the dancer mostly recount short episodes of Krishna’s life. Mystical Urdu love poems are also included in the repertoire.

The Technique

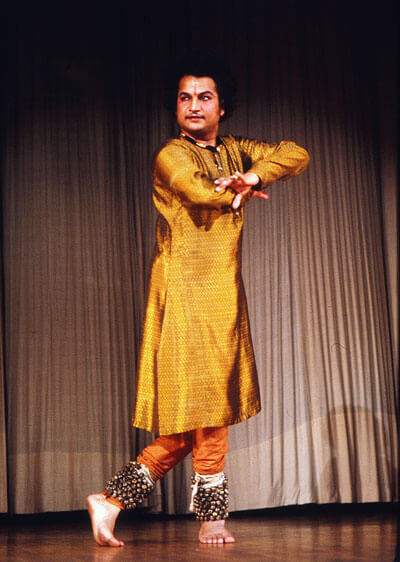

- Virtuosity of kathak Sakari Viika

- Hand and arm poses of kathak Sakari Viika

The basic standing position of a kathak dancer is with the left arm raised vertically and the right arm kept at shoulder level and bent forward at the elbow, the fingers of both hands decoratively extended. This basic stance already differs drastically from those stances that dominate the southern Indian lasya styles. It is asymmetric and linear in character, whereas, for example, in bharatanatyam, geometry and a stricter symmetry are favoured.

However, as kathak evolved from an older Indian dance tradition, much of its technique still echoes the influence of the Natyashastra tradition. These features include the division of the dance into pure nrtta and mimetic abhinaya sections as well as the use of the mudras, the symbolic hand gestures. In kathak the hand gestures do not have such a central role as in other solo forms. They are merely natural extensions of the dance gestures, though, of course, they carry symbolic messages.

The minute footwork, so dominating in kathak, is based on the so-called “flatfoot” technique, in which the whole sole of the dancer’s foot touches the floor. When the feet are slapped with great energy and speed against the floor, it seems that the dancer is almost flying. Jumps are also included in the technique, which in general attempts at an impression of fluidity.

The nrtta sequences, as mentioned above, are fireworks of rhythm. The dancer’s loud footwork, emphasised by the small ankle bells (ghunghru), give an essential addition to the aural aspect of the dance.

- Beginning of a pirouette Sakari Viika

- End of a pirouette Sakari Viika

- A kathak pirouette Sakari Viika

One of the characteristics of the kathak technique is the use of spins or pirouettes (chakkar), rare in most forms of Indian dance. The pirouettes, executed on the heel, are usually concentrated at the end of the number and provide it with a final climax in which up to fifty pirouettes can be included. It is possible that the pirouette technique derives from the ecstatic Sufi dances of Central Asia.

The abhinaya technique of kathak, although clearly related to the Natyashastra tradition, is more soft and less stylised compared with other solo forms discussed above. Neck movements are frequent but the facial technique is concentrated mainly on the eyebrows.

The Repertoire

- Long sequences in kathak are performed in sitting or crouching positions Sakari Viika

As is the case with the other solo dance forms described above, kathak’s repertoire also consists of small dance numbers, representing or combining pure nrtta dance and mimetic abhinaya technique. Usually a kathak programme is constructed so that it progresses in tempo from a slow beginning, including invocations and ritual greetings, to an extremely dramatic and fast ending.

The nrtta numbers are divided into shorter (tukra) and longer pieces (toda). Tukras usually concentrate on one particular aspect of dance, such as the gait or the pirouettes. Nrtta numbers include, among others, tarana, chaturang, adana, sargam, and tatkar.

- Krishna in a ball game; the abhinaya sections often deal with Krishna’s life Sakari Viika

There are several kinds of abhinaya numbers in the repertoire. The longest and most elaborate of them is thumri in which the dancer interprets the sung poem by gestures and facial expressions while often sitting on the floor in a decorative pose. Thus the focus of the number is completely on the abhinaya mime technique as well as on the dancer’s personal interpretation of the poem, which is often, to a great extent, improvised.

The themes enacted in the abhinaya sections are taken from Hindu mythology. The most popular themes deal with Krishna’s childhood and amorous youth with Radha and the gopi cowherd girls. Also common are themes related to the Puranas and the great epics, as well as to other avatars of Vishnu, particularly Rama.

The Costume

As already mentioned, the northern Indian miniature paintings give us information about the evolution of kathak costume. It seems that the skirt worn in the paintings by Krishna served as a kind of starting point for kathak dress. The full-length skirts of the women of the miniatures seem to be transparent, allowing a glimpse of the lower garments.

Nowadays there are several variations of kathak costume. They can be divided into Hindu and Moghul types, the former being formerly used at the Rajasthan’s Hindu courts and the latter in the Moghul context.

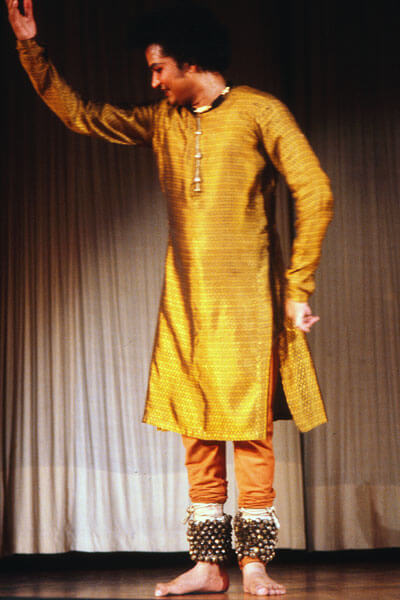

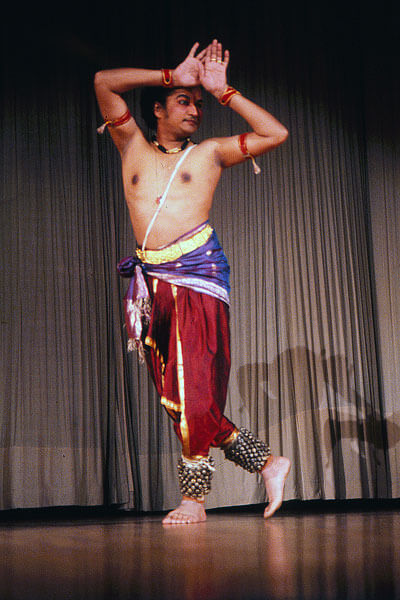

- Hindu-type costume for a male dancer Sakari Viika

The woman’s Hindu-type costume consists of a sari-like long skirt and trousers and often also the Moghul-influenced veil, while the men originally danced bare-chested, wearing a dhoti loin cloth, wrapped to form a kind of loose trousers.

The Moghul costume for women consists of churidar trousers, a long skirt and a blouse. According to the practice of purdah as well as the Moghul court etiquette, the semi-transparent veil was and still is used by the female dancers. The male dancers wear churidar trousers and a kurta shirt that is at least knee-length. In all cases the materials of the costumes are usually highly ornamented and valuable. The woman’s outfit also includes rich jewellery and the obligatory nose ring, which gained popularity during the Middle Ages.