Khon, “The Masked Pantomime”

- Phra Lak (Lakshmana), Phra Ram (Rama), Hanuman, and the Demon King Totsakan (Ravana) on a khon stage Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon is one of the most spectacular forms of Southeast Asian dance-drama. It can involve over a hundred actors, a large piphad orchestra, narrators, singers, and a chorus. Khon is often described as ’masked pantomime’. This is an apt term, for the khon actors do not speak their lines. They only enact their characters on stage by using expressive gestures and the whole vocabulary of Thai classical dance, while embodying characters solely from the Ramakien epic.

- Instruments of a piphad orchestra Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon employs decorative, painted and gilded papier maché masks covering the whole heads of the dancers enacting the demon and monkey roles. The masks and the glittering court and military dresses, different types of crowns, ornaments and attributes are still today believed to reflect the Ayutthaya-period prototypes.

The Question of Origin

One of the standard topics of Thai theatre studies is the origin of khon. Rama II (1809–1824) has often been mentioned as its creator, but it is now believed to be much older. The first written reference to this genre is an account of a khon play recorded by a French delegation visiting Ayutthaya in 1691. According to an inscription it was performed among other forms of entertainment in the early 18th century and since then it has regularly been mentioned in textual sources, such as royal decrees.

Nang yai shadow theatre has often been regarded as one possible source of khon. This view is based on the fact that it is known that there existed a specific form of khon, which was performed in front of a screen, similar to the white muslin screen used in nang yai. This could, of course, explain the many similarities which khon and nang yai share.

They both employ the same kinds of archaic verse, movement techniques, and characterisation. This could also explain one of the main characteristics of khon dance. The dancers tend to stand still in their decorative poses for longer periods and there is a clear tendency for silhouette-like attitudes and tableaux, corresponding to those depicted in the nang yai figures.

Another approach to try to decipher the birth of khon is connected to ancient ritual performances, such as Chak Nak Dukdamban (lit. pulling a giant serpent), which was performed in connection with coronation ceremonies. In this grandiose ceremony, also known as Indraphisekha, military officers and civil officials dressed as demon and monkey characters of the Ramakien enact the scene of the Hindu creation myth, Churning of the Milky Ocean. It is known to have already taken place during the Ayutthaya period. Similar kinds of rituals were also performed at other Southeast Asian courts, for example at the courts of Pagan, in Angkor, and in East Java.

A third source of khon, or at least for some of its movement techniques, may have been the krabi krabong or sword and baton dance, which is mentioned in an inscription as early as 1458. It employed the open-leg position and was accompanied by music. It was trained by princes and noblemen in order to learn the skills of martial arts.

Role Types

- An angry monkey Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon makes use of all the sub-techniques of Central Thai classical dance. In fact, they almost seem to have been created for the needs of khon. The noble humans employ the full scale of the natasin or Central Thai classical dance which was in the early 19th century influenced by the soft elegance of the lakhon nai court dance drama. The monkey and demonic characters have their appropriate basic movement techniques. Their movements are dominated by an extremely open leg position, the Indian-influenced characteristic of Southeast Asian martial dance, which has already been discussed several times. Indeed, the movement technique of the demons is believed to originate from the ancient Thai martial arts. Thus, the dance of the demons with its powerful stamping is aggressive in character, whereas the monkey’s dance has its acrobatic and playful elements. Their movements imitate those of real monkeys, thus adding yet one more element to khon’s complex movement vocabulary, that of the ancient animal dances.

The main role categories with their corresponding movement techniques are

- heroes (the major hero, Phra Ram, and the minor hero, Phra Lak);

- heroines (the major heroine, Nang Sida, and the minor heroine, Montho);

- demons; and

- monkeys.

Originally, all the characters wore masks, but since the nineteenth century only the demons and monkeys have worn them.

- A reconstruction of old-style khon in which the noble characters also still wear masks, Phra Lak (Laksmana) a golden one, and Phra Ram (Rama) a green one Jukka O. Miettinen

The khon masks cover the whole head and are made of papier maché, which is painted, lacquered, and decorated with inlaid glass or mother-of-pearl. They are stylistically related to Thai dance costume, and their bright colours and details, such as the shape of the nose, eyes, and mouth and the model of the crown, express the identity and rank of the character.

Grandiose Spectacle

- A battle between Pha Ram (Rama) and Totsakan (Ravana) Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon drama is the sum of varied elements. It shares its Ramakien-based narrative, characterisation, and movement techniques with the nang yai shadow theatre. Many of the conventions of movement are based on ancient martial arts. Before the introduction of firearms, warriors and even members of the court practised martial skills, repeating certain movement series, which could also be performed in a dance-like manner. These provided established movement patterns for dance-drama, especially the battle scenes.

- An audience scene at the court of Totsakan (Ravana) Jukka O. Miettinen

- An audience scene at the court of Totsakan with modern sets and lighting Jukka O. Miettinen

Another essential feature of the khon plays was provided by strict court etiquette, which is maintained at the courts of both Rama (Phra Ram) and the demon-king Ravana (Totsakan). This practice reflects traditional Thai court etiquette, which khon drama relayed to the members of the court and the royal bodyguard, who sometimes performed in the plays.

- Phra Ram (Rama) arrives at the battlefield, a grandiose khon spectacle performed outdoors Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon drama was originally performed outdoors. There was no scenery or stage props only a few Thai-style podiums with legs serving as seats or thrones. Traditional khon plays begin with an audience scene, either in Rama’s or Ravana’s palace. The ruler is surrounded by his court, arrayed according to rank, which is shown by the order of seating or the height of the seat or podium. Behaviour follows strict court etiquette, and no one may stand or walk while the ruler is seated. In the lengthy audience scene the conflict of the story is presented and its preceding events are narrated.

The most spectacular scenes are battles, which are often preceded by long negotiations and exchanges of messengers. The Ramakien specifically describes ancient battles and conflicts between nobles, which were bound by etiquette as strict as that of the court. After due preparation, the principal characters and their armies gather at the battlefield.

- Arrival of Pha Ram (Rama) on a carriage at the battlefield surrounded by his monkey army Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arrival of Totsakan (Ravana) with his demon army at the battlefield Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arrival of Pha Ram (Rama) Jukka O. Miettinen

- The tableau-like culmination of a battle scene between Pha Ram (Rama) and Totsakan (Ravana) Jukka O. Miettinen

Rama and Ravana enter from opposite sides of the stage in their traditional gilt Thai chariots with flame ornaments, drawn by men wearing horse masks. Wearing full regalia, they hold their ornamental bows in their hands. Ravana is followed by an army of demons, dancing menacingly and waving clubs. Rama is accompanied by his half-brother Laksmana, and a resourceful monkey army.

When the battle reaches its climax, Rama and Ravana step down from their chariots to engage in hand-to-hand combat. Finally, the victor raises himself in a heroic posture onto the thigh of the crouching loser to the acclaim of the audience. The victory scene is an almost picture-like static tableau with exact counterparts in the mural paintings and reliefs of Thai temples.

Recited Texts

Khon plays are accompanied by a piphad orchestra, chorus, singers, and narrators at the side of the stage. The narrators describe the events of the plot and recite the lines of the characters on stage with extreme expressiveness. As in many other Asian theatre traditions, the narrators in khon have a crucial role. They are as vital to the success of the performance as the dancer-actors, who move on stage according to the distinctly recited lines. Dancing in Thai dance-drama can be divided into two types: gestures illustrating the text, and dance proper accompanied by music. Both types are fully used in khon drama.

- Hanuman tries to seduce Banyakai in the khon play The Floating Lady Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hanuman succeeds in his attempt Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon plays last several hours, and they traditionally describe only a single episode of the Ramakien. Over the years, different versions of the khon texts have been made, and some of the versions have become especially popular. One such version is The Floating Lady, which is attributed to Rama II. It is an interesting example of a khon script for two reasons: first, it is quintessentially Thai, that is, it does not belong to the original Indian Ramayana, and secondly, its language is highly valued for its poetic qualities.

Types of Khon

Khon drama has experienced many changes and thus there have been several types of khon performances. The “khon in front of a screen” (khon na jor) has been mentioned already in connection with nang yai shadow theatre, to which it is most probably related. This ancient form has now disappeared although new experiments are occasionally done in order to combine khon and the shadow theatre.

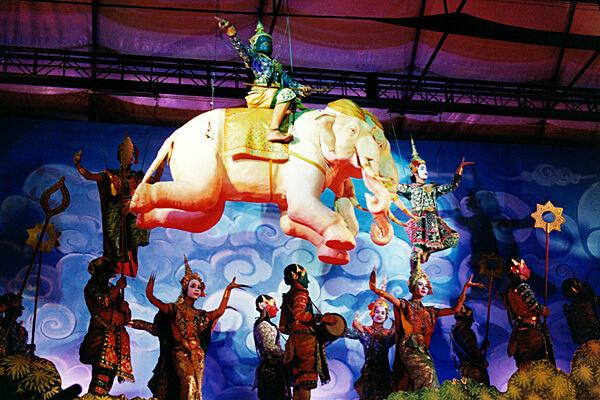

- Totsakan (Ravana) flees, disguised as the god Indra, with Indra’s three-headed elephant, a reconstruction of a 19th century style “khon in the air” performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Suddenly Totsakan attacks Phra Lak Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hanuman attacks the elephant and beheads it Jukka O. Miettinen

“Khon on a bamboo pole” (khon rong nok) refers to an archaic form of khon in which the actor-dancers sit on a bamboo pole while gesticulating to the recitation of the narrators. “Khon in the air” (khon chuk rok) refers to special performances, which are known to have been staged in the second half of the 19th century. It is characterised by complicated stage machinery, which is employed in order to create the impression of flying. This form was revived at the end of the 20th century.

“Court khon” (khon na jor) is a kind of chamber variation of khon. It was usually performed indoors without scenery and it concentrates on delicate singing and recitation. Its complete opposite is “outdoor khon”, which was and still is performed at public festivities in the ceremonial Sanam Luang Square in Bangkok and at other venues. It concentrates on big battle scenes in which singing and recitation are of less importance.

The most common form of khon in the 20th and the early 21st centuries is “khon performed on a Western-type stage” (khon chak). It is performed on a proscenium stage, which gradually became common in Thailand at the end of the 19th century. These kinds of productions often employ illusory stage sets with backdrops and modern lighting. The productions of the National Theatre of Bangkok often represent this type of khon.

Innovation and Revivals

As has already been made clear, khon has gone through several changes during its history. One is related to the appearance of female dancers on the khon stage. Khon was originally performed solely by males with female impersonators playing the women’s roles, but in the present performances of the National Theatre of Bangkok, women’s roles are usually played by female dancers. In some reconstructions of older types of khon, however, men can occasionally appear in female roles.

The main changes in the khon tradition have been in stagecraft and scenery. Khon plays were originally performed outdoors without props or sets, but in the nineteenth century, along with the increased popularity of realism and the new Western-style theatre houses, khon plays began to be performed on a Western-type proscenium stage with illusionistic, fairytale-like scenery. Modern lighting techniques are also used, including spots and now even laser lights.

- The triumph of the newly crowned Hanuman after he has succeeded in stealing the heart of Ravana and thus in destroying him Jukka O. Miettinen

Some attempts to reform khon drama do not involve its outward forms but its content. The Ramakien is a large work of literature, and the khon plays usually illustrate only single episodes. Like many other Southeast Asian forms of theatre, khon is of an epic nature. It usually presents a series of events, and does not focus on individual psychological features. In recent decades there have been experiments where the text has been adapted and compiled to portray the life of an individual character such as Hanuman or Piphek, the brother of Totsakan (Ravana).

- An altar with a khon mask in an actor’s dressing room Jukka O. Miettinen

Khon was originally a form of court theatre with strong sacred connotations, but after the revolution of 1932, after which Thailand became a constitutional monarchy, this union was partly dissolved. Despite all these changes, khon drama has retained many of its ritual features. In the actors’ dressing room is an altar where the masks of the mythical Teacher or Master Rishi and some of the Ramakien characters are revered. There is a similar altar at the side of the stage, where offerings are made before the performance. The actors make a respectful gesture of greeting before donning their masks, and the same gesture is made to the stage, which is regarded as sacred.

- The apotheosis of Pha Ram (Rama) in his home kingdom of Aoydhia, a modern khon production concentrating on the aspect of Prince Rama as an incarnation of the god Vishnu Jukka O. Miettinen

- Phra Lak (Laksmana), a scene from the same performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arrival of Pha Ram (Rama) and Pha Lak (Laksmana) at the battlefield, a scene from the same performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- A battle between Pha Ram (Rama) and Totsakan (Ravana), a scene from the same performance Jukka O. Miettinen

The National Theatre of Thailand has long been responsible for maintaining the khon tradition. It stages traditional and innovative khon plays from time to time, and in connection with state festivities the khon troupe of the National Theatre arranges grandiose open-air performances. The theatre groups of the universities perform more liberal interpretations of khon drama. Famous is the so-called Thammasat khon, established in the 1970s at Thammasat University in Bangkok by M.R. Kukrit Pramoj, a prince and a former Prime Minister. In this type of khon the rishi or hermit character, originally performed by Kukrit himself, speaks, taking liberties in commenting on current and even political matters.

In the late 20th and the early 21st centuries there have been various attempts to revive older forms of khon. In the 1990s a reconstruction of “khon in the air” was staged at the Wat Arun Festival in Thonburi, near Bangkok. Its stage machinery and scenery were based on a 19th century temple mural showing a similar kind of performance.

In 2008 a special khon spectacle was sponsored by the Queen in honour of His Majesty the King’s 80th birthday. It was a reconstruction of a khon performance originally produced in 1899. Its speciality is that its music is written down in Western notation, and a military band consisting mainly of Western brass instruments plays the music. The costumes and masks of this curiosity were reconstructed in the style of the late 19th century.

Many trends can be recognised in the khon tradition of today. Official performances are still obviously related to the dynastic cult of the ancient god king. These kinds of performances retain many of the changes khon has gone through during the 20th century while, at the same time, some smaller companies try to return to older performance practices. However, khon is also used as a basis for a completely new kind of interpretation.

- Prince Rama flying on his chariot in a khon spectacle in 2022. The SUPPORT Foundation of Her Majesty Queen Sirikit.

In 2018 UNESCO listed khon as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, which increased khon’s popularity in Thailand. Thus, the first large scale khon performance after the COVID pandemic in November 2022 was a huge success with wide media coverage and ten sold out performances in Thailand Cultural Centre. The production involved hundreds of dancers from various dance institutes while its visualisation combined modern high-tech stage technology with traditional Thai aesthetics.