The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644)

The Triumph of Kunqu or the “Elegant Drama”

The region south of the Yangzi River, Jiangnan (Chieng-nan), maintained its importance as a cultural centre. It was not only a centre of the arts and passive resistance; it was there where a successful rebellion arose. It was led by a Buddhist monk, Zhu Yuanzhang (Chu Yüan-chang), who made the city of Nanjing (Nanking, Nan-ching) and its surroundings his stronghold. With his troops he marched up to the north and deported the last Mongol ruler from the country.

This heralded the beginning of a new period, the Ming dynasty. Although foreign oppression was now over, it did not change the awkward situation of the scholars and artists. The liberator, Hongwu (Hung-wu), which was the name he was known by when he was the ruler, turned out be an unpredictable despot. During his time artists were in danger of losing their heads and scholars their tongues, if any critical remarks could be detected in their plays. It resulted in the phenomenon common in Chinese history: at the beginning of a new dynasty censorship of plays was meticulous, almost to the point of paranoia.

During the Ming dynasty the Yuan zaju lost its popularity to the southern forms of operas. The quick and feverish music of the north gave a way to the soft southern melodies. Many regional opera forms evolved. Then, as well as now, the regional styles differed mainly in the dialects in which they are sung, and in their melodies. Otherwise they, more or less, share the same kind of basic aesthetics.

An important early Ming-period dramatic script is Pipa ji (p’i-p’a chi) or The Story of the Lute by Gao Ming (Kao Ming) (1307–1370). It is about a youth who flees from his parents and his young wife to attend the imperial examination. After passing it successfully, he is forced to marry the daughter of a prominent minister. Back home the young scholar’s parents die during a famine. The wife dutifully takes care of their funeral rites, after which she heads for the capital in search of her husband. She carries with her the only possession she has, a lute. The minister’s daughter understands the love her husband feels for the girl and agrees to accept her into the household as a second wife.

The Suzhou (Su-chou) region became an important economic and cultural centre. By the Grand Canal system wealth was brought to this region with its large concentration of population and active communication with the outside world. It became a centre of fashion and set the standards for customs and taste throughout the rest of China. The region’s local kunshan (Kunshan qiang, Kun-shang ch’iang) opera style gained great popularity in the 16th century.

Wei Liangfu , who was a composer and a singer, concentrated on a renewal of the Kunshan Style. He created a new musical style, which was regarded as “the most melodious and romantic since the Tang period”. Its leading instrument was a bamboo flute, whereas the northern styles were dominated by string instruments.

Kunqu, Kun Opera or the Elegant Drama

Video clip: Dou E. A kun-style reconstruction of 13th century play, Dou E yuan or Snow in Midsummer. Veli Rosenberg

The new form of opera, fashioned by the composer and singer Wei Liangfu, is kunqu (kun-ch’ü). It is the oldest form of Chinese opera still being performed. The music has a strongly plaintive quality. With its flowing melodies and soft and supple note of the bamboo flute, it is a typically southern style of opera. Its singing is characterized by its long notes and elaborated ornamentation. It is said that the general effect of kunqu music is that of “undulating waves”.

- Kun opera Longing for the Worldly Pleasures tells about a young monk and a girl who escape together to experience love. Jukka O. Miettinen

During the Ming dynasty kunqu emerged as the most popular and most patronised of the many theatrical forms and it retained its national dominance until the 19th century. It was patronised particularly by the educated elite, the scholar-officials and the literati. The acting technique is most demanding, since the delicate singing is combined with constant dance-like movements. Because of the complexity of both its language and acting technique, the educated courtesan actresses, trained in several arts, dominated the kunqu stage for a long time.

The complex imagery of classical poetry and the need for increasingly ornate language and music led to longer plays. The appreciation of this kind of art form naturally demanded a great deal from the audience, too. The dialect used was the Suzhou dialect, a local dialect of Chinese, which was not understood universally in China. The increasing sophistication and the use of local dialect were the factors that led to the gradual unpopularity of kunqu in the early 19th century, when a new and more popular form of opera, the Peking Opera, gained a wider audience in northern China.

The so-called Taiping (T’ai-p’ing) Rebellion in the mid-19th century isolated the southern region, which had traditionally been the stronghold of kunqu. The kunqu, already in decline, never regained its former status while the northern Peking Opera replaced it in popularity. The pattern of dramatic construction and expression developed through the kunqu were carried over into the Peking Opera, although this new style was devised for different, less sophisticated audiences.

In the 1920s and 1930s the famous Peking Opera actor Mei Lanfang, together with a kunqu scholar, established a society to revive the kunqu. Different attempts had been made in this direction for decades. In connection with this revival a northern kunqu troupe was founded, and its style was called beikun. At the time of writing this material, the beikun theatre has declined to some kind of semi-kunqu, semi-Peking Opera style, struggling to survive among other theatre forms in Beijing.

- Chinese opera styles are characterised by stylised facial make-up. Jukka O. Miettinen

- Kun opera actor prepares his make-up by applying red over the white ground, which symbolises beauty and youth. Jukka O. Miettinen

The southern kunqu style was called nankun. South Chinese nankun groups can be found, for example, in Shanghai and in Nanking, the latter one probably representing the most authentic kunqu style at the moment. For generations many have been afraid that this unique opera form will completely decline and disappear. In 2008 it was, however, officially included in UNESCO list of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity, and in the same year a stylised kunqu scene was one of the highlights of the giant opening show of the Beijing Olympics in 2008, broadcast all over the world.

The kunqu plays

The birth of kunqu was due to the close co-operation of musicians, such as Wei Liangfu, with talented play writers. Chinese is a tonal language, and thus when it is sung, its relationship with accompanying music is close and specific, an important phenomenon to be further discussed later. The tones, according to whether they are level, ascending, or first descending and then ascending, or descending in pitch, affect the actual meaning of the word and consequently create a kind of musical basis within the language itself.

Video clip: Fragrant Lady a reconstruction of the play Lian Xiangban in the 16th century kun opera style Veli Rosenberg

The first writer who was able to create dramatic scripts and language matching the fashionable kunqu melodies was Tang Xianzu (T’ang Hsien-tsu) (1550–1617). As he was contemporaneous with Shakespeare he is sometimes called the “Shakespeare of China”. His works are regarded as the epitome of the dramatic literature of the Ming period. His plays are still praised for their harmonious structure, deep emotions and sophisticated style.

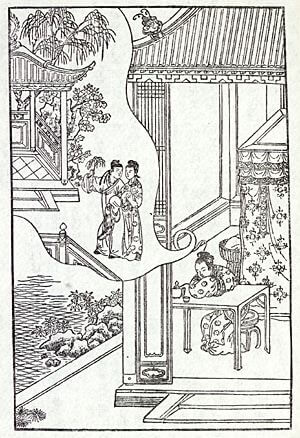

- A Ming-dynasty wood block print showing a scene from Tang Xianzu’s play, Peony Pavilion. The Archives of Finland–China Society

His style is often called the “dreaming” Ming style. This is because of the so-called dream scenes, which were both his innovation and his trademark. Through these dream scenes or sequences, in which the leading character falls asleep, it was possible to make a character’s secret or unconscious hopes or fears visible. The most famous of these kinds of dream sequences is in Tang Xianzu’s most popular opera, The Peony Pavilion, Mudan ting (Mu-tan t’ing).

In the play, a young lady falls asleep in a peony garden. In her dream she meets a young, handsome scholar and falls deeply in love with him. When she awakes and understands that everything was only a dream, she mourns herself to death. The effect of Tang Xianzu’s dream scenes were so moving that young female spectators, it is said, went out of their minds, and even committed suicide. Later, Tang Xianzu’s dream-scene technique was imitated by several less talented playwrights, and some of them substituted Tang Xianzu’s magical poetry with simple stage effects.

Kunqu dramas are of a high literary standard and their poetic language is complex and not easy to understand for modern audiences. They employ the full scale of role categories developed in the earlier theatrical styles. They include the sheng or the male roles, the dan or the female roles, the chou or the comic roles, and the jing or the painted-face categories (with their numerous sub-categories, to be discussed in connection with the Peking Opera).

- A scene from the kunqu opera Spilling the Water in Front of a Horse. Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from the kunqu opera Spilling the Water in Front of a Horse. Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from the kunqu opera Spilling the Water in Front of a Horse. Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from the kunqu opera Spilling the Water in Front of a Horse. Jukka O. Miettinen

The themes tended to be romantic and concerned which such things as lovers’ sorrows. Thus the leading characters in kunqu plays are often a young lady and a young scholar. This is not always the case. A play that is renowned for its dream sequence, called Spilling the Water in Front of a Horse, Maqian po shui (Ma-ch’ien p’o shui), recounts the story of an elderly, less successful scholar and the tragic end of his selfish and over-ambitious wife, played by an actress who has specialised in the coquette female characters, called hua tan.

One landmark in the revival process of kunqu was the performance of a play called Fifteen Strings of Cash, Shiwu guan (Shih-wu kuan) in Suzhou in 1957. The play had been seen performed as Peking opera, but in Suzhou it was again produced in the original kunqu style. Kunqu plays were very commonly adapted to the Peking Opera style, which had inherited so many elements from the earlier kunqu.

- Opera White Snake tells about supernatural snake spirits who on earth assume the forms of beautiful ladies. Here the Blue Snake handles spears in an acrobatic fighting scene. The Archives of Finland–China Society

A kunqu play that is also popular as Peking opera is Longing for Worldly Pleasures, which, in fact, had been adapted to the kunqu repertory from an even older southern style. It is a kind of monodrama for a virtuoso huadan actress who interprets the romantic longing of a young Buddhist nun. Another play, very popular both as kunqu opera and Peking opera, is The White Snake, Baishe zhuan (Paishe chuan). In the play, the spirit of a white snake turns into a young woman and marries a young pharmacist. A monk is determined to destroy the snake and her marriage. The white snake goes through numerous hardships and ends up by being locked up in the dungeon of a pagoda.

The White Snake is exceptional as a kunqu, since it includes fighting scenes that employ movements from the martial arts. That was not common in the southern kunqu tradition, whereas the later Peking Opera makes full use of them. Before turning to the birth of northern Peking Opera, which gained the status of the national style after the kunqu, it is time to look at what kinds of operas were and still are performed in other regions of China. The play was created from an old story by Tian Han in the beginning of the 20th century.