The Twentieth Century

The twentieth century brought an end to the isolated tranquillity of Bali. For centuries Balinese culture and theatre had been able to develop undisturbed. Now, influences flowed from all directions: from both the West and the island of Java. However, throughout their history, the Balinese have combined new ideas with old traditions, and foreign influences have stimulated Balinese theatre even in politically unstable times. The increasing mass tourism of recent years has created a new audience, which, however, has not always had a solely positive effect.

The Kebyar Style

- I Nyoman Mario, one of the originators and exponents of early kebyar Theatre Arts Monthly 1936, Rose Covarrubias

After the Dutch take-over of Bali in 1908, the traditional central court of Klungkung in Eastern Bali lost its former importance, and the focus of cultural life partly moved to North Bali near the Dutch colonial centre of Singaraja. New gamelan and dance clubs were established, and their competition led to a cultural renaissance in the 1910s–1930s. The most sensational novelty was a style of gamelan and dance called kebyar, which came about through a competition between two villages in creating musical and dance compositions.

With its wildly complex dynamics and its florid, embellished sound, the gamelan gong kebyar is probably the most expressive style of Balinese gamelan music. In 1914 it was used to accompany the first performance of kebyar dance, the kebyar legong, performed by two maidens dressed as men. The new style became popular in only a few years.

It was further developed by the legendary dancer I Nyoman Mario, who in 1925 presented the first performance of his own innovation, kebyar trompong. In it the performer both dances and plays the trompong, an ancient percussion instrument placed in front of the gamelan.

Kebyar is an abstract non-narrative dance, where the performer interprets the rapidly changing moods of the gamelan with his or her movements and expressions by combining elements from various older dance styles.

A characteristic feature of the style is that it is mostly performed in a crouching position, with the dancer often raising the hem of a narrow skirt resembling older legong costume with one hand. The dancer’s bare arms trace expressive movements in the air while the hands and fingers are extended into delicate, quickly changing gestures.

- The expressive eye movements and the use of the fan are characteristics of kebyar Sakari Viika

The dancer uses a fan to accentuate the rhythmic and emotional patterns of the gamelan accompaniment. Along with the costume, many movements and gestures also derive from legong. Several dance versions were developed at the height of the kebyar fever.

The Panji semirang portrays the Princess Candra Kirana of the Panji Tales disguised as a man, a typical feature of the kebyar intermixing male and female roles. The kebyar bebancihan, or neutral kebyar, is in turn a form of dance that can equally be performed by both men and women. Generally speaking, the kebyar style has had a decisive effect on the aesthetics of twentieth- century Balinese dance and music.

The Western Art Colony

I Nyoman Mario, one of creators of kebyar, was greatly admired by both the Balinese and foreigners living on the island. Over the decades Westerners have had an increasing influence on the development of theatre and dance. Dutch colonial officials were, in some cases, patrons of the renaissance of North Balinese theatre, and the German-born painter and composer, Walter Spies, who settled in the small town of Ubud in Southern Ball, was in many ways instrumental in reshaping Balinese arts.

Among the Western artists residing mainly in Bali, mainly in the village of Ubud, were the Mexican painter Miquel Covarrubias and his wife, Rose Covarrubias, who actively documented Balinese dance and theatre. Among the Western residents was also the American composer, Colin McPhee. His writings and compositions proved important in popularising gamelan music in the West.

Walter Spies was also the founder of the modern Balinese school of painting. He was visited by a wide range of Western artists and scholars from Charlie Chaplin to Margaret Mead, and he assisted European film-makers in planning the first documentary on Bali. For this film a new type of dance was created, the kecak, which has found an established place in the Balinese standard repertoire. These early Western admirers of Balinese culture were instrumental in organising the first visits of Balinese artists to the West.

Kecak

- Prayers before a kecak performance Jukka O. Miettinen

The kecak (cak) is based on the ancient dance chorus tradition. Men seated at the dead of night in circles around a large oil lamp chant the syllables “cak-kecak-cak” with immense strength and astounding rhythmic precision. The fast abdominal breathing and the bursting vocal of this gamelan svara or “voice orchestra” lead easily to hyperventilation and trance.

- The chorus arrives at the area of the stage Jukka O. Miettinen

- In the middle of the feverish chorus the demon King Ravana kidnaps Princess Sita Jukka O. Miettinen

- Ravana hypnotises the chorus Jukka O. Miettinen

- The chorus takes part in the events by both singing and gesturing Jukka O. Miettinen

It is generally believed that Walter Spies combined this archaic ritual tradition with a scene from the Ramayana, where Rama, Sita, and Ravana appear in the midst of the suggestive chorus to enact the scene where Sita is abducted. Sitting, singing, and dancing with their hands and upper torso, the chorus becomes, among others, the Ramayana’s army of monkeys.

In the climax, the chorus, with a heightened feverish pitch, rises as it takes part in the events of the drama. At present, kecak is frequently performed in many villages, but the shows are mostly intended for tourists.

Since the 1970s several new versions of kecak have been created. One of them is the all-female kecak, which had its premiere at the Bali Arts Festival, in 2004.

New Dances

As the reputation of Bali spread throughout the world, Balinese dance troupes were invited to the West. In 1931 the first full group of Balinese dancers and musicians performed at the Colonial Exhibition in Paris, and in 1953 a Balinese group toured Europe and the United States.

The Balinese artists were enthusiastically received, and their performances had a profound effect on many Western artists, including Antonin Artaud, one of the pioneers of modern Western theatre, who projected into Balinese performances his own concepts of “total theatre” and “Oriental dance”.

In view of the Western audiences, I Nyoman Mario created a repertoire for the tour with short numbers, easily comprehended by foreigners, such as Oleg Tambulilingan, a composition portraying the mating of bumblebees. Mario’s choreographies have found an established position in Balinese dance repertoire.

Tambulilingan already described animals, and since then various animals have inspired Balinese choreographers to create numerous short, non-ritual dances. Besides the animal themes, the Balinese dance of the mid- and late-20th century has been dominated by a kind of gender play. Cross-dressing and particularly women performing the male roles have become popular.

Arja, Balinese Opera

- Entrance of a court lady in an arja performance Jukka O. Miettinen

- A hero (performed by an actress) and a heroine in a love scene Jukka O. Miettinen

- Male actors appear as ministers and courtiers Jukka O. Miettinen

Arja, a kind of popular opera was created in 1825 for the funeral of a Balinese prince. It was originally performed by an all-male cast. In the 20th century it emerged as a form of sung drama, while women replaced the male actors. The twentieth century has been, in many respects, a period of feminisation in Balinese theatre; in many of the traditions, such as sendratari, actresses often play the roles of noble heroes, while the practice of female impersonators has almost been forgotten.

The all-female casting of arja is believed to have led to the predominance of vocal virtuosity, for at the same time the Balinese language has replaced the ancient Kawi court language. Arja became a true folk opera, popular all over the island. It is performed, in Balinese fashion, by dancing, and its plot material is based on The Adventures of Prince Panji, Balinese legends, and even Chinese stories.

Like other Balinese dance-dramas, arja combines the most refined elements of dance and music with the earthiness and grotesque humour of clowns and servants. Along with village performances, arja can also be seen on television.

Influences from Java

When Indonesia achieved independence after a severe period of political strife, Bali became part of the new republic, and again after four hundred years of isolation Javanese influences increased in Balinese culture. In the field of dance, a new, nationalistic concept of art emerged, which was partly modelled after the socialist countries, and engendered a number of dances portraying the life of various ethnic groups and social classes.

These included the Peasants’ Dance and the Weavers’ Dance, which reflected the ideas and alms of the new national government. In Bali the kebyar was chosen as the basic technique of these new, relatively simple dance compositions. The new ideas led to many experiments, which, however, did not achieve any permanent popularity.

Sendratari, The Balinese Version of Pan-Indonesia “Ballet”

The sendratari dance-drama, created in the 1960s after Javanese models, shows no signs of diminishing popularity. Sendratari (seni: drama; tari: dance) is a spectacular form of dance- drama, originally created in 1961 for the Prambanan Festival in Central Java to provide entertainment for both foreign and local tourists.

Compared with other forms of classical dance-drama, it is more concise and more action-orientated, as the dialogue, recitation, and all ritual elements have been excluded. A narrator sitting in front of the gamelan presents the plot and the lines, while the dancers and large dancing choruses enact the story. Sendratari makes full use of Western stage techniques with coloured lights, spotlights, and other effects. Its overall dramaturgy mainly resembles Western narrative ballet.

The subject of the original sendratari performed at the Prambanan Festival, in Central Java, was the Ramayana. Soon after the first sendratari performance in Java, artists from the Balinese College of Performing Arts (KOKAR) staged, for the first time, a Balinese version of sendratari called Jayaprana, based on a popular Balinese love story, a kind of local “Romeo and Juliet” tale.

In 1965 KOKAR presented the Sendratari Ramayana, a Balinese novelty based on the Ramayana, which became even more popular than Jayaprana, and many villages soon established their own sendratari groups. This genre combines elements of indigenous Balinese dance forms, such as legong and kebyar, as well as Javanese dance traditions.

The sendratari can be regarded as a kind of pan-Indonesian official state art, although in Bali the style has achieved an increasingly local flavour. Since the inauguration of the Bali Arts Festival in 1979, a large-scale sendratari spectacle has usually been the main event of the festival. Sedratari has influenced many other genres, especially in the way in which they have been “modernised”.

Drama Gong, Spoken Theatre

Sendratari influenced the birth of yet one more novelty in 1966. It was drama gong, a mainly spoken form of Balinese theatre, which is accompanied by gamelan gong kebyar, the most expressive of all Balinese gamelan styles.

Drama gong is performed in the vernacular on a proscenium stage with melodramatic effects borrowed from Western theatre and with painted scenery. The stories are usually from the Panji cycle, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, or from Balinese legends. Drama gong is still popular and troupes are hired to perform at various occasions. TV also regularly broadcasts drama gong productions.

The Present and the Future

- Learning to play gamelan Jukka O. Miettinen

- Girls practising dance Jukka O. Miettinen

At present, Balinese theatre life continues to be highly active. Despite new experiments traditional theatre has not lost any of its vitality. While Bali has established its reputation as one of the world’s best- known tourist paradises, its classical dance and theatre have become its true trademarks. Ritual performances take place as before, children learn music and dance, and popular performances gather together both local and foreign audiences.

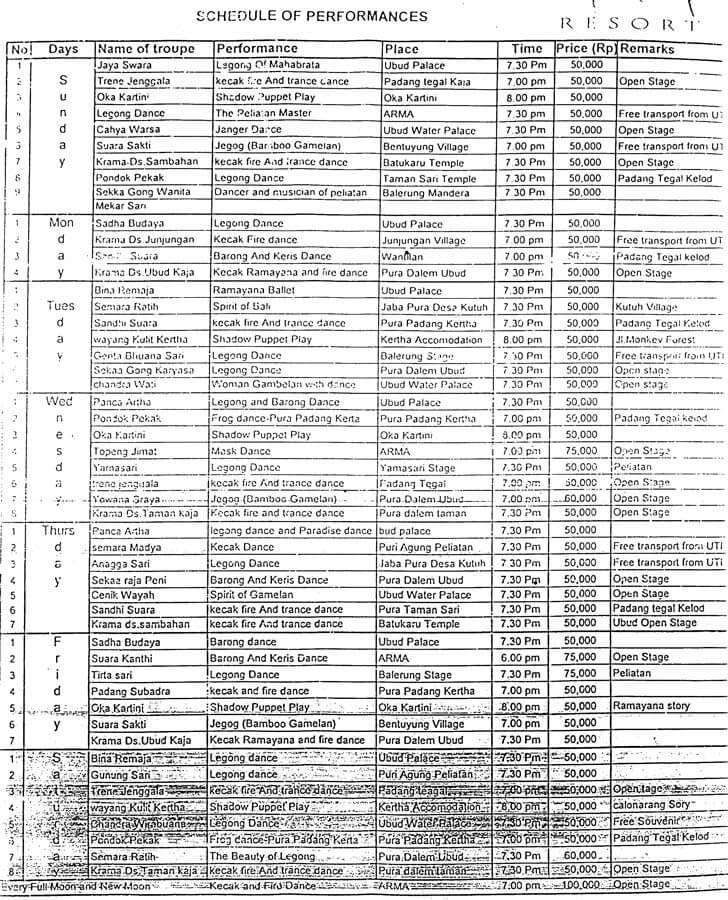

- The weekly schedule of performances in the Ubud region in 2009

Tourists and travellers come to Bali in large numbers (annually some 2 million), and every visitor usually attends one or two performances, while the more serious traveller may easily study Balinese dance in some of the numerous private schools operating on the island. Ubud and its surrounding villages continue to attract tourists and offer an opportunity to see several good quality performances daily.

Tourism has, naturally, affected the performance practices, which has led to a number of essential changes. Previously, most performances were related to calendar feasts, but today they are held daily. The tastes, or assumed tastes, of tourists dictate the duration and structure of many performances.

- One of the novelties of the late 20th century is the all-women gamelan Jukka O. Miettinen

Most tourist shows consist of a potpourri of the main Balinese dance styles, often performed in a shortened and even somewhat simplified form. Even the annual Bali Arts Festival is basically an international event, and not the kind of traditional religious festivity that in earlier years provided the main theatrical performances.

In spite of reforms and mass tourism, there has also been serious work in Bali to maintain the old forms of theatre. The Akademi Seni Tari Indonesia and KOKAR institutes of dance and theatre, operating along pan-Indonesian lines, strive not only towards a new synthesis but also to study and revive old traditions.

In the early 1970s cultural leaders decided that the most sacred wali dances must not be secularized or performed commercially for outsiders. This decision showed a clear concern for the dance and theatre traditions of the island, and their innermost sacral core. The dualism of the present situation may, however, explain the secret of the vitality of Balinese theatre.

Throughout history, Balinese theatre and dance tradition has been susceptible to change, but its sacral core has remained unchanged. Bali will most probably remain one of the most interesting loci of Asian dance and theatre if Balinese theatre, while responding to the challenges of mass tourism, still retains, as it seems, its deep significance for the Balinese themselves.