The Twentieth Century

In the early 19th century the British first gained control of Southern Burma, converting Rangoon (Yangon) into a Western-style colonial centre. In 1866 they finally extended their dominion to Upper Burma. Partly because of the uncompromising attitude of Thibaw, the last king of Burma, the British used violent means to gain power. The court was almost completely destroyed toward the end of the 19th century. The fate of the court tradition was sealed when the enormous wooden palace complex of Mandalay with its court theatre burned down in the final stages of World War II.

By this time Burmese court theatre and dance had given rise to a thriving folk tradition, which still partly reflected the ideals of the court. Western culture, introduced by the British, had a strong effect on Burma. In the early years of King Thibaw’s reign, Western theatre groups had performed for the king himself, and Burma was possibly one of the first countries in Southeast Asia to have a Western-type theatre with a proscenium stage, backdrops and a curtain. This type of stage was imitated even by the marionette theatre, of course, in mini size. A general trend of secularisation now permitted the surviving court forms to be performed to ordinary audiences and live actors to perform even in plays based on the Jataka stories.

- Star dancer Po Sein in a costume imitating the court dress of Upper Burma Reproduced from a photograph in the Rangoon National Museum by Jukka O. Miettinen

In the 1910s and 1920s Burmese theatre was marked by a cult of star actors, the main figures being Po Sein and Sein Kadon. Po Sein’s semi-fictitious biography is one of the few books on Burmese theatre that have been published in English. The star cult developed extravagant forms as the star actors invented means to publicise their personalities. Po Sein performed with a “bodyguard” of two British ex-soldiers, while Sein Kadon sometimes danced in a costume with blinking electric lights. Despite these aspects of sensationalism, their artistic merits were undeniable, and Po Sein bequeathed to posterity not only his repertoire but also a dance style named after him.

Independence

When Burma became independent in 1948, the new government began to revive theatre and dance. State schools were established in Yangon and Mandalay in 1953. The renowned performer Oba Thaung created the basic movement series for the use of these schools, comprising 22 basic movement units (gabyar-lut), still used in dance training in Myanmar. As elsewhere, the theatre was also used to propagate nationalism and the new political ideology, and East European puppet theatre specialists were invited to reshape the marionette theatre.

- Dancers representing various ethnic groups perform a dance holding the flag of the Union of Myanmar Jukka O. Miettinen

Myanmar has huge National Theatres in Yangon and Mandalay, but they are rarely used for actual theatrical performances. Official groups of Burmese performers have performed in other Asian countries, in Europe and in the United States. During the present junta’s regime, however, official tours have been rare because of the negative attitude towards the junta’s policy in the Western world. Universities and art schools are closed on and off, and they have been moved to the outskirts of towns in order to keep the students isolated from any political activities, a situation that is anything but fruitful for cultural life.

Popular Pwe

At the moment traditional theatre and dance in Myanmar mainly survive in the few tourist shows staged for the diminishing numbers of tourists arriving in the country despite its awkward political situation, and as part of the entertainment at temple festivals and other public festivities. Pwe performances lasting all night are staged in various parts of the country, often in connection with religious festivals.

- A pwe poster being painted in Yangon Jukka O. Miettinen

Large temporary halls and stages of bamboo are erected for these “variety shows”. At dusk, local pop idols come on the stage to sing their hits and sometimes versions of Western pop music. After midnight the classical dancers begin their performance, which lasts until morning. In the late 20th century television was still rather rare in Myanmar, and movies were seldom shown in the rural areas. The world of cinema (often enacted by live actors), pop culture, folk entertainment, and remnants of old court culture all coexist in these pwe performances. The most common ritual performances are still the nat pwe, which are continuously staged throughout the country.

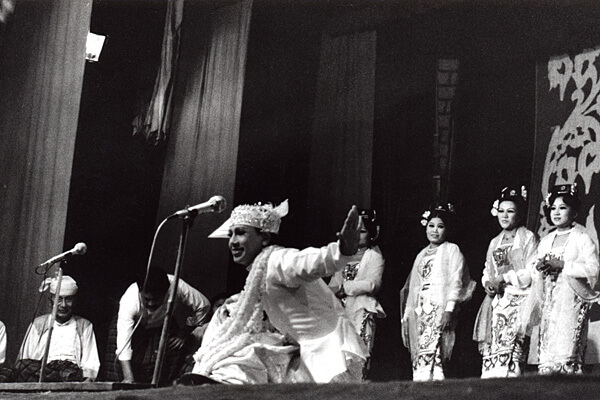

- A scene from a pwe variety show Leif Lönnqvist