“Theatre of the Capital” or the Peking Opera

A Creation of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911)

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) China was again ruled by foreigners, this time by the Manchus. They, however, greatly appreciated many aspects of Chinese culture and thus the Qing dynasty was, in fact, a fruitful period for the arts. The beginning of the dynasty was overshadowed by riots and revolts but a long period of peace began during the reign of the art-loving Emperor Kangxi (K’ang-hsi) (who ruled 1662–1722).

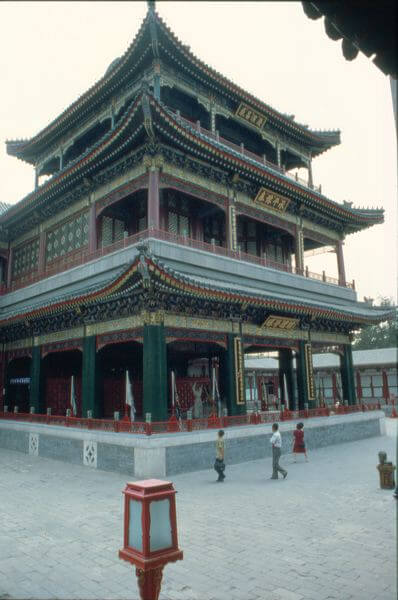

- The largest and technically most complex stage structures in China are usually the imperial stages. This one is in the Summer Palace, near Beijing. Jukka O. Miettinen

The popularity of the sophisticated southern kunqu or kun opera was already declining. It was still admired by the educated elite, but its southern dialect and complicated lyrics made it difficult to be appreciated in North China. There, audiences preferred their own regional styles with familiar dialects, stories and melodies. Many regional opera styles from different parts of the country gained popularity in Peking at the beginning of the new dynasty.

The opera-loving Emperor Qianlong (Ch’ien-lung) (who ruled 1736–1795) invited troupes from the province of Anhui to the capital to perform their local style, the bangzi opera or the clapper opera, which has already been discussed above. They performed at the Emperor’s eightieth-birthday celebrations, but their performances proved so successful that the troupes stayed on, becoming increasingly popular.

- White Snake was originally written for kun opera but is also often performed as a Peking opera. The snake sprits wander on earth in human form. The Archives of Finland–China Society

Over a period of time they began to adapt the technical characteristics of other local styles. One very important person in this process was the bangzi actor Cheng Changgeng (Ch’eng Ch’ang-keng), who, in his performances, combined elements from, among others, the kunqu and the clapper opera. After an evolution spanning decades the fusion process led to a new form of opera, called jingju (ching-chü) or “theatre of the capital”. In the West it is known as the Peking Opera.

In the beginning this new style was known only in the capital, where it gained great favour in the reign of the Empress Dowager Cixi (Tz’û-hsi) (1835–1908). In the 1860s mobile troupes of performers also started to perform Peking Opera outside the capital area. It spread around the country and thus gained its status as a “national style”. In 1919 Peking Opera was performed for the first time outside China, in Japan. Soon Peking Opera troupes were also visiting the United States and Russia, taking this art form to within reach of western audiences and theatre reformers, such as Brecht, Stanislavsky, Craig etc. Peking Opera is still today the most widely studied and performed traditional form of theatre in China. In 2010 it was added to UNESCO list of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity.

Peking Opera Plays

In the process of constructing the new Peking Opera, many elements were adopted from the former “national style”, the kunqu. There are, however, also clear differences between these two styles. As stated already, kun operas employ southern melodies as well as sophisticated and complex poetry. Because the poetic scripts were usually performed from the beginning to the end, the plays were often very long. To be fully appreciated kunqu required a deep knowledge of literature.

In Peking Opera the written play is generally only a kind of working script, not a piece of literature. It consists of basic plots which have been abstracted from different sources, such as older kunqu plays, from popular stories, historical romances, and themes from storytellers’ repertory. Generally speaking, the authors remained anonymous and in many cases the scripts were compiled by actors.

The scripts include only a very few, if any, stage directions. This is probably because they were written in the context of established theatrical conventions which were familiar to all the performers and the audience. The dialect used by the Peking actors is predominantly Mandarin Chinese, although it contains elements from other dialects as well.

The Peking opera plays can be divided into two basic groups. They are the wenxi (wen-hsi), or the “civilian plays” and the wuxi (wu-hsi) or the “martial plays”. The wen plays deal with people’s everyday lives, and often include love stories. The wu plays are regularly based on the historical stories of heroic battles and they may have patriotic overtones. One popular source for this kind of plays is the famous Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Sanguo yanyi (San-kuo yen-i).

The Manchu rulers were originally warriors, and thus the wu plays suited their taste better than emotional wen plays. The wu plays require vigorous, often violent action, such as fighting, acrobatics, sword display etc. Thus it was through the wu or the martial repertory, which dominates the Peking opera repertory, that the martial arts and acrobatics became an inseparable element of the Peking Opera.

Peking Opera repertory can further be divided according to which skills or aspects are emphasised in the plays. Thus one can speak of, for example, “singing plays”, “recitation plays”, “plot plays”, “fighting plays” etc. In the Peking opera tradition it is very common that whole plays are not always shown from the beginning to the end. Instead, a performance can concentrate on one act of a whole opera. Kinds of multi-act performances, called zhexi (che-hsi), are also very common. They consist of famous highlights or single acts from popular operas.

Spaces for Theatre

Chinese opera has been performed on several kinds of stages, from simple tea houses to temporary stage structures put up in market places or country fairs, and to court theatres, to private chamber theatres, and from the beginning of the 20th century, most often in the western kind of large theatre houses.

There exist good examples of old stages and theatre houses around China. Several small pavilion-like stages belonging to a temple or a private palace still exist, and imperial, three-storied stage structures with stage machinery can be seen in Beijing, both in the Forbidden City and at the Summer Palace. The most famous of the Qing-dynasty private tea-house theatres is at the 18th century residence of Prince Gong, in Beijing. The so-called tanghui (t’ang-hui) or performances at private parties, in spaces not designed for performances, have also been popular.

A theatre space typical of the early phase of Peking Opera was the so-called xiyuan (hsi-yüan) or “opera courtyard”. There, a square stage was surrounded by the audience on three sides. The performances could last the whole day. Later, in a type of theatre called the “old style theatre”, the wooden stage floor was covered with a thick woollen carpet to make the acrobatic scenes safer for the performers. At the rear of the stage hung an embroidered curtain, which was the private property of the leading actor of the day. Seeing the curtain, audiences knew who was going to play the lead.

During the heyday of Peking Opera, at the end of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century, the opera activities were centred on the Qianmen Gate Tower area, in the old commercial centre of Peking. There were some ten theatre houses and hundreds of important Peking Opera artists lived and practised their art there.

From the 1950s onward Chinese opera has increasingly been staged in huge theatre houses and cultural palaces constructed during the Communist regime. This has affected Chinese opera in many ways. Some performance practices have been altered, curtains are used between acts or even scenes, and modern lighting technologies are employed. The most disastrous effect created by the huge performance spaces, completely alien to the intimate scale of Chinese operas, is the use of microphones and amplifiers. It not only destroys original sounds and the balance of the operas, but also restricts some of the dance-like movements of the actors.

The Stage of Imagination

Peking Opera, like other traditional Chinese opera styles, employs non-naturalistic ways of conveying stories. The performances rely upon symbolic presentation, in which illusions are created by non-realistic acting rather than by illusionary stage sets. Chinese opera stage is an empty space, or a kind of a plastic space, which by means of acting technique and verbal hints can turn from a forest to a palace or from a poor hut to heavenly spheres.

Traditionally, a raised platform which extends forward, with three sides facing the audience, has served as the opera stage. Behind the stage hangs a back curtain with two curtained doors leading backstage. The left door was used for the entrées and the right door for the exits. When making their entrances the characters usually introduce themselves by hinting at some of their main characteristics, such as “I am a selfish scholar called so and so” or “I am poor orphaned girl called so and so” etc.

After the introduction, the characters jump into the drama and into the imaginary world of its story. By their words or, more often, movements and gestures, they create the spatial surroundings required. For example, gestures of pushing and pulling indicate opening or closing a door or a window. A certain kind of movement of the body and legs indicates “stepping over a threshold” etc. Stage props are used very economically.

- Certain set elements, such as mountains, clouds, waves etc. can be carried on the Peking opera stage. Here stage assistants are holding a movable set that shows a city gate. Jukka O. Miettinen

Sometimes necessary visual elements, such as stylised clouds, mountains or, for example, a city gate, painted on cloth or cardboard, are carried by the actors or stage assistants. Two pieces of cloth carried on both sides of an actor indicates that the person is travelling on a sedan chair, and waving flags informs the audience that there is a horrendous storm going on.

Generally, however, all that is needed on a Peking Opera stage is a table and a couple of chairs. The space around them may be a courtroom, a study, a palace etc. This is indicated by the colours and patterns of the silken covers of the furniture. For example, if the silken chair covers and tablecloth have a dragon pattern, the scene is taking place in an imperial palace, but if the covers are greenish or blue with orchid patterns, the place is a scholar’s study etc.

- Susan, a tragic heroin, is questioned in a court room. Jukka O. Miettinen

The placement of the furniture can also have different meanings. If a chair is placed in front of a table, the audience knows that the scene is set in an ordinary home, but if it is behind the table, it indicates that it is question of an official or a ceremonial occasion, possibly in a palace or in a courtroom.

Thus, in a traditional performance the whole illusion of the space and different places and surroundings mainly depends on the hints given by actors employing their various acting skills. However, in the big, modern theatre houses, stage sets, lighting technology etc. are now used. This process started in the international city of Shanghai, where the modern theatre houses and the use of setting appeared from 1908 onwards.

The Actor’s Skills

- The fighting scenes of Peking opera are constructed from well-rehearsed acrobatic units. Jukka O. Miettinen

- Training in acrobatics. Jukka O. Miettinen

In traditional Chinese theatre the acting technique or, to be precise, “actor’s skills” are called xigong (hsi-kung). They refer to the acting tradition and methods formulated during the centuries. They are divided, for example, into the hand, the eye, the body, and the feet techniques, all of them related to physical expression, such as acting, mime, dancing, and acrobatics. Besides those skills, actors must also master very demanding singing and recitation skills.

- It takes years to learn to handle the long water sleeves properly. Jukka O. Miettinen

- It takes years to learn to handle the long water sleeves properly. Jukka O. Miettinen

- It takes years to learn to handle the long water sleeves properly. Jukka O. Miettinen

In addition to these main methods, the actor must have a command of several sub-techniques or “supporting techniques”. They include, for example, the skills related to the handling of certain parts of the costume, such as the long white silken extensions of the sleeves, the so-called “water sleeves” shuixiu (shui-hsiu). Though it seems very easy and natural, handling them is actually very demanding, and students practise it for years. These silken strips extend the actual movement of the actor. They can also indicate several things, such as talking sides or presenting gifts, or they can simply express powerful emotions.

Other supporting techniques are the fan skills, related to the handling of the fan, which can be used in many ways, for example as a symbol of many things, such as a wine cup, a butterfly etc. Further skills with a beard refer to the many ways in which an artificial beard can be manipulated. Anger, thoughtfulness, hesitation and many other moods can be expressed by the handling of the beard. Further supporting skills are related, for example, to the manipulating of the hair and the handkerchief.

In the non-naturalistic, symbolic acting style of the Chinese theatre, many things can be told or illustrated by these supporting skills. A good example is the riding whip skills. Riding a horse is indicated by a riding whip the actor holds in his hand. The colour of the whip indicates the horse’s colour, and the horse’s movements, such as galloping, running for a long time, the horse’s tiredness etc., are indicated by the movements of the whip combined with the actor’s other body movements.

Peking Opera professionals divide the acting skills into three realms. “being accurate” indicates a correct combination of the skills, while the second realm, “being beautiful”, focuses not only on the technical execution, but on the interpretation’s aesthetic values and the accuracy of the portrayal of the character. The highest of the three realms, “having a lingering charm”, is more difficult to put in words since the highest quality of artistic performance often seems to avoid exact definitions. For example, the singing of a certain star actor has been described as “being gentle as weeping and lingering as a thread”.

Theatre of Types

In the stylised and symbolic world of Chinese opera the roles represent abstractions of human attributes. Actors do not aim to create psychological portrayals of certain individuals. Instead, they rely on fixed personality types whose specific qualities are taken for granted by the audience. The way in which these qualities are then interpreted reveals the actor’s skills and the level of the actor’s artistry.

The entry of emperor Xiang Yu (Hsiang Yü) in the opera Farewell to my Concubine, Bawang bie ji (Pa-wang pieh chi). Veli Rosenberg

As has been seen in previous chapters, the role categories of Chinese theatre developed during a long period lasting, according to literary sources, over a thousand years. Starting from the Tang period onwards, different theatrical styles employed more and more role categories with their fixed characteristics, types of make-up and costuming.

The Peking Opera inherited its four main role categories from kunqu and other earlier theatrical forms and yet enriched them, for example, by also adding among them martial role types with acrobatic skills. The four role categories are sheng or the male roles, dan or the female roles, jing or the “painted face” roles, and chou, the comic roles. Within these main categories there are further several subdivisions to define the type variations of the main character.

- In the Peking opera’s dynamic fighting scenes the martial art techniques are employed in several ways. The costume of general has flags in its back. Sometimes a general can have also long pheasant plumes protruding from his headgear. Originally they were.

The main sub-categories of the sheng or the male roles are laosheng or the middle-aged or old men, usually with beards, and the xiaosheng or young, handsome men, most often scholars. The old man type sings with a rather low, natural voice, while the young man blends in his singing both natural voice and falsetto, which indicates his youth. Furthermore, the male roles, as is the case in all other role types as well, are divided into civilian and martial types. The martial men, or the wusheng, usually wear a pompous costume imitating ancient armour. Some of the higher military officers have pheasant plumes in their headgear, sometimes even two metres long. Their expressive handling is a special skill of its own.

- A meeting of powerful generals. Among them there are also female warriors. Many of them are known in the Chinese history. Jukka O. Miettinen

Other special skills, characteristic of martial types, whether belonging to the male, female, comic or painted face categories, are the martial arts, acrobatics and virtuoso displays of skills related to weaponry. The martial actors practise these skills year after year so that they can master short acrobatic and fighting sequences from which longer scenes are then constructed. The climax of a military scene often takes the form of a breathtaking display featuring dynamic tumbling and somersaults while swords and spears fly in the air. These thrillingly fast scenes are accompanied by feverish percussion music.

Similarly to the male roles, the dan or the female roles are also divided into the civilian and wudan or martial role types. Otherwise, the three major sub-categories of the dan roles are the ginyi or the gentle and often noble young lady, the huadan or vivacious, often coquettish woman, and the laodan, or old woman. All of them have their own acting and singing techniques.

The noble young woman, the ginyi, or the so-called “blue-robed woman” (she often wears a black robe with blue borders) sings in a high falsetto. This singing technique is due the fact that until the 1920s only male actors were allowed to perform on the Peking Opera stage and thus actresses must use the falsetto technique of female impersonators of older times. The ginyi actresses concentrate on singing, graceful dance-like movements and masterful handling of the water sleeves.

Instead of singing, the huadan or vivacious female type concentrates on mime acting. These lively characters usually belong to the class of ordinary people. The laodan or old woman type is characterised by its natural voice range and body language which indicates old age.

Both the old man and old woman types wear barely any make-up, only some lines around the eyes and the mouth. The young woman role types paint their faces first with matte white. Then deep red is added around the eyes, the nose and on the sides of the face. The deep red is graded with the white of the cheeks and the nose. This pinkish make-up, shaded with deep red and highlighted with white, indicates beauty and the glow of youth. The make-up of the youthful male character is also approximately similar.

The most spectacular types of make-up belong, as the name “pained face” already indicates, to the jing characters. In China the types of facial make-up have a history of at least over a thousand years. The early types of make-up were simple; the face was painted red, black etc. Over the centuries the make-up became more complex and reached its culmination in the hundreds of intriguing make-up designs of the Peking Opera’s jing characters.

According to these “face maps”, all recorded in special pictorial manuals, the audience immediately gets information about the inner qualities of the characters portrayed. A red face, for example, indicates loyalty and uprightness, a black face a forthcoming character, a blue face pride and bravery while a white face indicates cunning and treachery. The most surprising of these types of make-up are those in which all the traces of the anatomy of the human face are faded away by a completely abstract facial painting reminiscent of a colourful tornado or of some kind of cosmic explosion.

Similarly, as the other role types, the jing characters are also divided into martial and civilian characters. The wu jing characters concentrate on the martial arts while the wenjing concentrate on singing. Their voice range is natural, approximately equivalent to a western baritone voice. In the early period of the Peking Opera it was the jing actors who were the leading stars of this art form. Heroic generals, patriotic heroes, legendary rebels, gods and other mythological characters are included in this role category. They often wear thick-soled shoes, which add as much as 20 cm to the actors’ height, creating the impression of larger-than-life personalities.

The fourth basic role category of the Peking Opera is the comic chou characters. The military clowns, wuchou, are trained in acrobatic and martial arts while the civilian clowns or the wenchou concentrate on mime. The white patch surrounding their noses and eyes makes the chou characters easy to recognise. The chou category is regarded as the oldest of the character types and has its origin in the adjutant play of the Tang dynasty. They include all kinds of personalities, such as farmers, traders, playboys, high-ranking officials and sometimes even emperors. They can be either good or bad characters. They do not often sing; instead, they use pure colloquial language so that their jokes are easy to understand.

As mentioned, within these four basic role types, there are further several subdivisions to define the type variations of the main characters. The costuming of all the character types is based on Ming-period prototypes. In the same way as their facial make-up, their costumes also give the audience information about the personality, profession and social status of the characters. In the Palace Museum in the Forbidden City in Beijing, there is a Qing-dynasty manual which lists the costumes of the characters in some one thousand Peking Operas.

The Social Status of the Actors

As in many other cultures in older times, the social status of actors in China was very low, too. Whether they belonged to the private troupes of educated men, traders or officials or to the wandering troupes, the actors were regarded merely as prostitutes. Their social status is reflected in the fact that for a long time the actors were excluded from the official examinations. It was generally accepted that the actors did not choose their profession, but were forced to do so because of poverty or, for example, because the head of the family has received a criminal sentence.

There were periods when famous actresses who were courtesans were widely admired and some high-class admirers even married them. However, these kinds of marriages were not common, because of the actor’s reputation of having low morals. Mixed companies, with both men and women, were popular in the 13th and 14th centuries, but after that they were, due the strict moral codes of Neo-Confucianism, banned.

During the Ming dynasty the tendency was already towards companies with performers of one sex only. The later world of the Peking Opera was completely a male domain. Until the 1920’s the actors, the playwrights and the musicians were all male, and so was the audience. As all the actors were men, they also performed the female roles. Boys and men excelling at impersonating female roles were a constant headache for officials, since attractive actors were popular sex objects among the homo- or bisexual male audience. Thus, many actors were obliged to serve high-ranking admirers with their sexual favours.

There were also, of course, personalities among actors who were admired by all levels of society purely because of their artistry and innovations. The beginning of the Peking Opera was the golden age of jing actors, who often played the roles of elderly statesmen, emperors, rebels and ministers. For decades they overshadowed the dan or the female impersonators. One of the brightest stars of the Peking Opera stage was Mei Lanfang (1894–1961). He not only brought the dan roles into focus again, but in many ways he influenced the Peking Opera’s development in the Republic of China and even during the early periods of the People’s Republic.

Mei Lanfang, a Legendary Female Impersonator and an Innovator

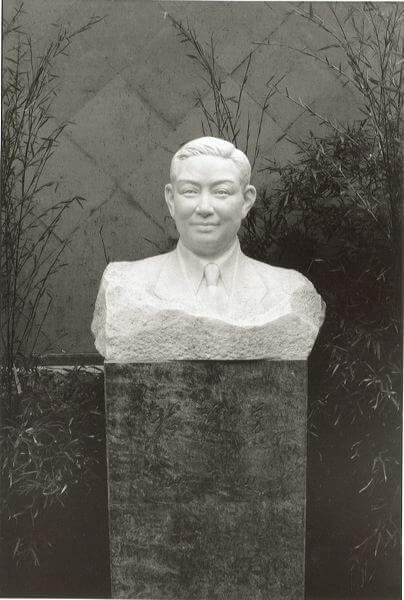

- A portrait of Mei Lanfang, the most well-known Peking opera actor of the 20th century. Mei Lanfang Museum, Beijing

Mei Lanfang is without doubt the most celebrated Peking Opera actor, both at home and abroad. He was born in Peking into a famous dan, or female impersonator, family in 1894. He began learning acting at the age of eight and made his stage debut at the age of ten. He created a sensation in Shanghai, where he worked for a longer period absorbing the new trends of the international city’s theatrical life.

He was a specialist of the noble female type, but was able to expand his acting to some other female types as well. He admired the old kunqu and was instrumental in its revival. However, he also created completely new dances, which are still popular today. He also created “modern” operas with stage sets, contemporaneous costuming etc. He was the head of the first Peking Opera troupe ever to perform abroad. In 1919 he performed in Japan and in 1929 in the United States.

His performances, especially those in the Soviet Union in 1935, had far-reaching consequences, since among the full houses there were several important pioneers of modern theatre, such as Konstantin Stanislavski, Bertolt Brecht, and Gordon Craig. Brecht found many elements in Mei Lanfang’s art which inspired his theories of the Epic Theatre.

During the early period of the People’s Republic Mei Lanfang was instrumental in deciding the fate of the traditional Chinese theatre. As a celebrated artist and an influential, cultural and political personality he was able to persuade Chairman Mao of Peking Opera’s value as the creation of the people of China, while at the same time the Communist party was banning all art forms related to religion and the imperial past. It is very much due to Mei Lanfang that the tradition of Chinese theatre continued through the middle part of the 20th century.

Related article by Stefan Kuzay: A Concise History of Theatre in Imperial China