Topeng, Mask Theatre

Java is the home of several mask theatre and dance traditions, which are commonly referred to as wayang topeng (wayang: shadow or puppet; topeng: mask). They are believed to have evolved from early shamanistic burial and initiation rites. Mask traditions universally contain shamanistic features, for when an actor puts on a mask he gives up his own identity and embodies the character of the mask, usually a mythical being such as a demon, a supernatural hero, or a god.

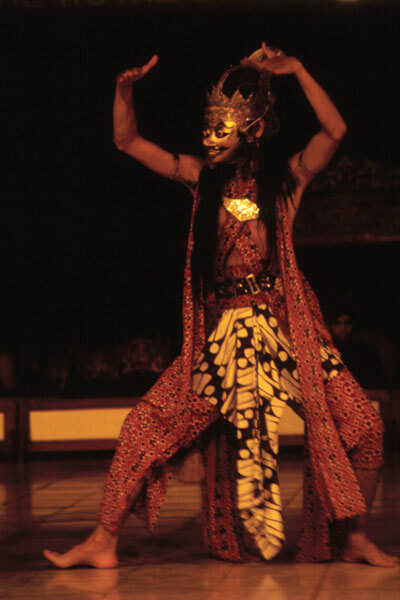

- The dance of the amorous King Klana from the Panji Story in Yogyakarta Jukka O. Miettinen

The Origins and Stories

The earliest known literary reference to wayang topeng is from 1058, and mask theatre is believed to have been very popular in the kingdoms of East Java over the following centuries. This led to the birth of wayang wwang, a spectacular form of court theatre, where some of the characters are believed to have worn masks.

Two main traditions of topeng developed: the impressive dance-drama of the court, and the village traditions, which still contain ancient shamanistic elements. Throughout the history of topeng, the “major” court traditions and the “minor” village traditions have been in a constant state of interaction.

Topeng is often based on the Mahabharata and the Ramayana epics, among other sources, but from a very early stage The Adventures of Prince Panji has been the most popular source of its plot material. This story cycle was created in East Java during the Majapahit dynasty. Its hero, the handsome Prince Panji, combines features of earlier historical and mythical figures.

Prince Panji became the Javanese ideal hero par excellence along with Arjuna of the Mahabharata and Prince Rama of the Ramayana. By the end of the fourteenth century, the Panji romance spread to Bali and other parts of South-East Asia, where it is known in several versions.

Topeng Dances

Full-length topeng performances have become rare, but topeng dance numbers are still often presented. Popular items of the repertoire are the introductory dances of Prince Panji and Princess Candra Kirana, allowing them to display their respective psychological qualities with classical dance patterns. In topeng these are usually faster and more expressive than in other forms of Javanese dance-drama.

An especially popular number is the so-called Kiprah dance of the enamoured King Klana (also Klono, Kelana) with his red mask. It most probably evolved from ancient ritual dances, and is known in several versions throughout the island of Java. For example, in the kraton of Yogyakarta it survives as the classic Klana topeng dance, and on the island of Madura it has its own highly different variants.

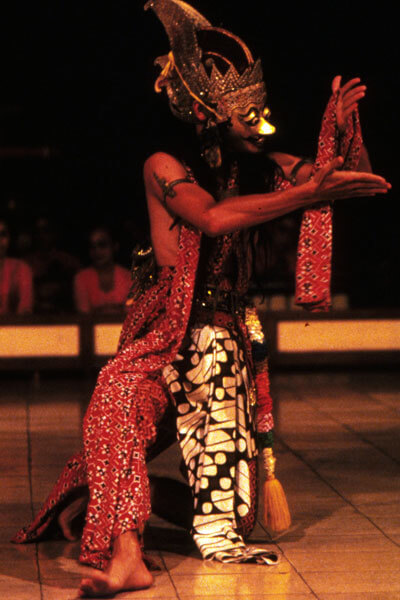

- King Klana wearing a rare golden mask; Klana topeng dance of Yogyakartan tradition Jukka O. Miettinen

- King Klana wearing a rare golden mask; a Klana topeng dance of Yogyakartan tradition Jukka O. Miettinen

- King Klana wearing a rare golden mask; Klana topeng dance of Yogyakartan tradition Jukka O. Miettinen

- King Klana wearing a rare golden mask; a Klana topeng dance of Yogyakartan tradition Jukka O. Miettinen

The dance expresses the yearning of King Klana, who has fallen in love with Candra Kirana. He imagines meeting his beloved and, with extremely expressive dance movements, enacts all the gestures of a vain man in love: he spruces himself up, arranges his hair, dresses in his best clothes, and plans to give a present to the object of his affections, who never appears. King Klana’s dance is usually performed in the energetic dance style of a strong male figure, but it also exists in a noble alus version, where the character is more refined, though still a desperate lover.

Styles of Topeng

The decreased popularity of mask theatre is usually explained by the spread of Islam. When the Central Javanese Mataram kingdom was divided into two in 1755, it was the kraton of Surakarta that inherited the ancient wayang topeng tradition of Mataram and its old masks. In Yogyakarta, wayang wong, which developed in the late eighteenth century, replaced the spectacular mask theatre performances of the court, but the old mask sets are still revered in the kraton as royal pusaka heirlooms.

- Masks of a hero and a heroine, East Javanese wayang topeng malang Jukka O. Miettinen

Today, in the kraton of Surakarta and Yogyakarta, topeng is performed from time to time, although mostly as solo numbers. In addition to the rarely performed court topeng, popular forms of this genre survive and are performed, especially in the villages of western Central Java. East Java and the island of Madura have their own mask theatre traditions.

- Wayang topeng batavia is a popular form of mask theatre from Jakarta, West Java Jukka O. Miettinen

Topeng mostly thrives in Sunda in West Java, where Cirebon with its small kraton has been the traditional centre of topeng. Alongside the court performances, the villages around Cirebon still have their own vital mask traditions. The folk forms of topeng include topeng batavia, a relaxed variant of topeng with a lot of elements of slapstick comedy. It has been performed in the area of the capital, Jakarta.

The Masks

In all parts of Java the topeng masks share the aesthetics based on the iconography of the wayang kulit and particularly wayang golek puppets. Carved out of wood they also resemble, however, the faces of the three-dimensional wayang golek puppets. Their stylization is almost abstract, and the oval masks in downward tapering form are usually slightly smaller than a human face. The faces of the noble characters are taut, narrowing towards a delicate chin, and the noses are sharply ridged and pointed. The eyes are elongated, and the mouths are small.

Strong characters, such as King Klana, wear energetic masks with upturned noses and wide-open, round eyes. The colour symbolism is the same as in the wayang golek puppets: noble characters have white or golden masks, although Prince Panji’s mask is usually green. The masks of the strong characters, like King Klana, are usually red.

- Topeng masks from Cirebon, West Java Jukka O. Miettinen

The various local traditions clearly differ in style. In Central Java the masks are almost triangular; the masks of east Javanese wayang topeng malang retain their own archaic stylisation; and the masks of Cirebon are perhaps the most abstract with almost symbol-like faces. The mask sets and collections on display in the National Museum in Jakarta, the Museum of Yogyakarta, and in some kraton museums demonstrate not only the local variations in mask styles but also their excellent artistic level.