Wayang, The World of Shadows and Puppets

- Wayang kulit shadow theatre is the origin of many other theatre forms in Java and Bali Jukka O. Miettinen

Wayang kulit (wayang: literally shadow, sometimes puppet; kulit: leather or skin) is still the most popular form of shadow theatre in all Asia. It has been extremely important in the development of Javanese theatre, as most of the other forms of classical theatre have derived their story material, stylisation, and many performing techniques directly from it. Wayang kulit set the aesthetic standard of Javanese theatre, and partly Balinese theatre as well.

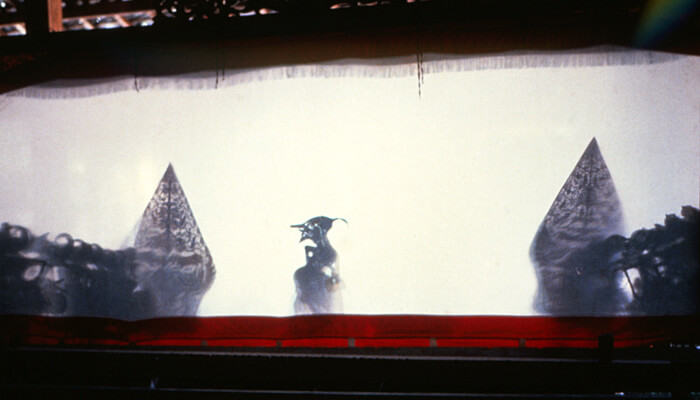

- Wayang kulit narrator-puppeteer in action behind the screen Jukka O. Miettinen

The stagecraft and equipment are relatively simple, the primus motor being a single narrator-puppeteer, dalang, manipulating the leather puppets on a simple white screen and acting as a narrator to the accompaniment of a gamelan orchestra. It is, however, an art form of immensely rich and intricate symbolism and philosophical content.

Video clip: The end scene from a wayang kulit shadow play, which is based on the epic Mahabharata Reijo Lainela

Shadow drama gave rise to other forms of puppet theatre, for example, wayang klitik with flat wooden puppets and wayang golek with three-dimensional rod puppets, which are discussed in separate sections. Although these forms of theatre are highly developed, and wayang golek still thrives, they are clearly surpassed by wayang kulit in popularity and complexity.

The Origins

There are two theories concerning the roots of Javanese shadow theatre. According to one theory, it came from India together with the Ramayana and Mababbarata epics during the long process of Java’s Indianisation. The other view maintains that Javanese shadow theatre has ancient indigenous roots. This is often supported by the fact that part of the shadow-theatre repertoire is based on pre-Hindu story cycles, and that all the technical terms of the genre are Javanese and not derived from Sanskrit or other Indian languages.

The earliest record confirming the existence of shadow theatre in Central Java dates from AD 907. In the East Javanese period, shadow theatre is believed to have been adopted by the Hindu courts of Bali during the long process of its Indianisation. The Balinese puppets still bear strong resemblances to the so-called wayang-style reliefs in East Javanese temples, discussed above, which are believed to have shared a common style with the contemporary East Javanese shadow puppets.

Present-day Javanese shadow puppets are, in turn, believed to have evolved into their extremely elongated and almost non-figurative style during the period of Muslim rule, thus reflecting Islam’s ban on making a human image.

Story Material

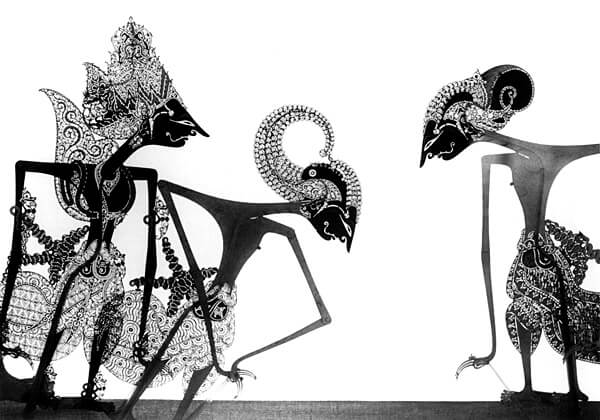

- Negotiations between the heroes of the Mahabharata Jukka O. Miettinen

The story or plot of wayang kulit as well as other Javanese drama performances is called lakon, roughly meaning the course of events or action. The plots are derived from various sources, for example, the Indian Mababbarata and the Ramayana, the East Javanese Prince Panji cycle, and later Muslim stories.

- The noble Prince Panji Jukka O. Miettinen

The four oldest cycles, dealing with the ancient history of Java, are collectively named wayang purwa (purwa: primeval, original, ancient). This includes both pre-Hindu material and lakon based directly on the Mababbarata and the Ramayana epics, whose heroes are regarded as the mythical ancestors of the Javanese. Sometimes the lakon are faithful to the original texts, but in many cases the epic heroes have been removed from their authentic contexts and have been written into new, purely Javanese, fantasies.

There are several hundred lakon. They serve merely as guides to the performances, including lists of scenes and personages, and descriptions of the action in the actual play, which in practice includes a great deal of improvisation not written in the lakon. However, a lakon follows a more or less standard structure.

The Structure and Symbolism of the Play

The play begins with audience scenes in the palaces of opposing monarchs, where the main conflict is presented. In the ensuing sections, the opponents send messengers to each other until they finally meet in person. Whilst preparing for battle, the hero will experience many doubts and inner conflicts.

The climax is a great battle, which is also a drastic turning point in the action. Finally, the victorious noble hero presents himself in his full glory at the home palace, and the plays usually have happy endings, the obligatory victory of the right. The themes are highly ethical, and the mood is generally serious, although the whole includes comic scenes with stock clown characters, slapstick, and even topical satire. Javanese theatre thus combines highly noble qualities with earthy comedy and even obscene grotesqueness.

On a philosophical, one could almost say an esoteric level, the play, as a whole, symbolises the human life cycle. The first part symbolises youth, the middle part adulthood, and the final part old age. The steps from one period to the next are emphasised by the change of the mode in the accompanying gamelan music.

On the deepest philosophical level wayang kulit as a whole, including the screen, puppets, dalang etc., represents the cosmic human body, a conception derived through Hindu-Buddhism and Tantrism from the Indian concept of purusha, the primeval cosmic man.

Dalang

Wayang kulit is, to a great degree, the art of the narrator. The performance of the dalang is the focus of the whole, often 10-hour-long performance, which traditionally begins at 9 p.m. and ends at sunrise. The dalang is also responsible for the rituals performed in connection with the play, and he must know by heart the main lakon, which are in a way revived with the addition of much improvisation.

The dalang have traditionally had a priest-like role, and the profession has passed on from father to son. Today, dalang are also trained in special schools, but they are still highly respected members of their communities, the best dalang being famous throughout the island.

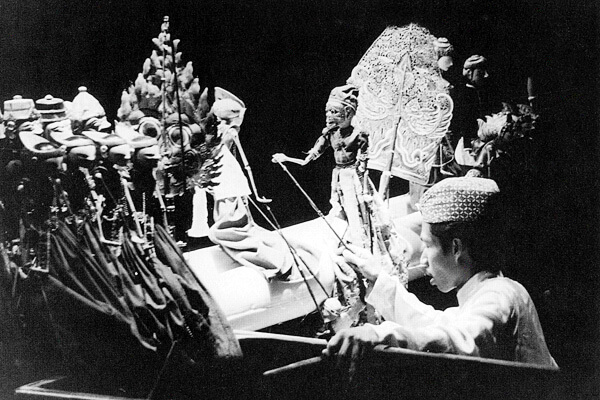

- Dalang operating the puppets and improvising the whole night show Jukka O. Miettinen

The dalang thus carries on the ancient oral tradition passing on the main body of classical literature, but at the same time he must be able to improvise and add even the most topical items to the whole. He must also be skilled in recitation, singing, the vocal characterisations of the roles, and the elevated and vulgar levels of the language, along with manipulating the puppets in front of the screen.

The dalang also displays expert knowledge of the music so essential to the performance. He leads the gamelan, an ensemble of up to thirty musical instruments: gongs, metallophones, xylophones, drums, flutes, zithers, and stringed instruments along with a chorus of female singers. One set of metallophones carries the recurrent melody, which is elaborated by other metallophones, xylophones, and gong sets, with the drums leading the rhythm, while another set of metallophones gives the dalang his pitch.

The gamelan accompaniment is indeed an integral part of the performance. Each principal character has his or her own musical theme or Leitmotif, and the gamelan drastically accentuates the three decisive turning-points of the performance, changing from the rather low-keyed accompaniment of the beginning to an ever higher pitch and faster tempo towards the end.

The Puppets

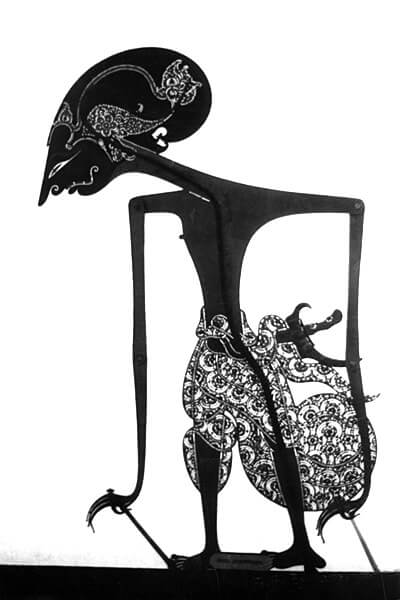

- Hanuman, a wayang kulit puppet Jukka O. Miettinen

The wayang kulit puppets, skilfully cut and chased in leather, are in themselves works of art following strict iconographic rules. A single performance may require the use of 100–500 puppets, varying from some 20 to 100 centimetres in height. The body of the puppet is usually depicted frontally, but the face and feet and the extremely long movable arms and hands are in profile.

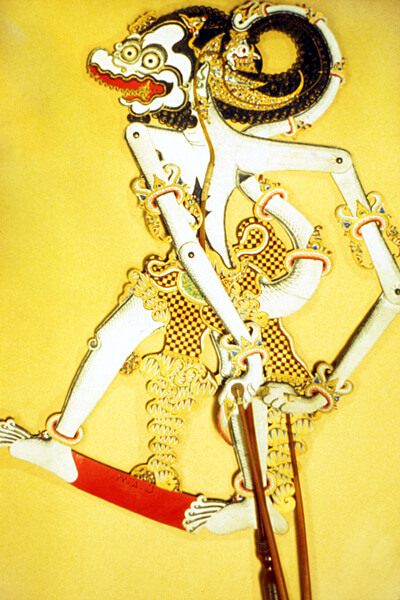

- Princess Sita and Prince Rama from the Ramayana Jukka O. Miettinen

The different characters, as well as their social status and psychological qualities, are marked by the size, colour, and other details of the puppet. There are, for example, fifteen eye shapes, thirteen nose shapes, and eleven mouth shapes, which together with specific costumes, headdresses, crowns, and jewellery typify the characters. The noble, so-called alus, characters are usually small, the strong gagah characters are larger, and the demons full of aggressive power are the largest.

Like the genre as a whole, the puppets of wayang kulit form an endlessly rich world of their own, a kind of science, which to an ever-increasing degree leads the initiated viewer into the secrets of the “wayang world”. The noble hero puppet, for example, follows the Javanese hero ideal of utmost beauty. His body must be slender and well proportioned his nose long and pointed, and his eyes must be shaped like soya beans. He must also look downwards, a reference to self-control and humility, the greatest virtues of Southeast Asian heroes.

The stronger characters may look straight ahead, and the more arrogant ones may even look upwards. The noses of the strong characters point upwards, and they have round, bulging eyes. The requirements of the male hero also apply to the royal princesses, whose refinement is taken to the extreme.

Colour symbolism gives added detail to the characterisation of the puppets, specifying their mood or temporary emotional state. Gold, the dominating colour, indicates dignity and serenity; black is a sign of anger or maturity; red is for tempestuousness; and white is the colour of youth.

To make matters more complicated, the principal characters can be represented by several puppets during a single performance, according to the situation, mood, or age. For example, Arjuna of the Mababbarata, the Javanese hero par excellence, has thirteen different puppet shapes.

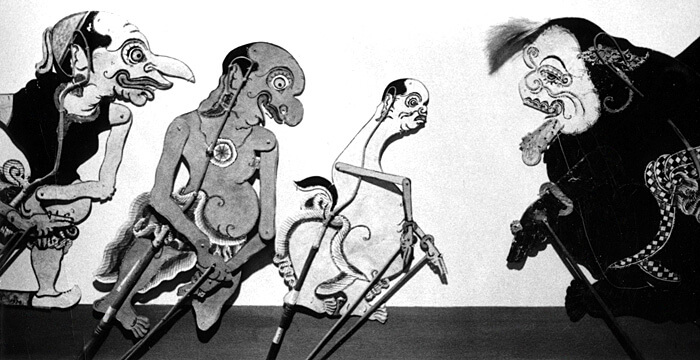

Punakawan, the Servant Clowns

- Semar, the “mother and father” of the clown servants, is regarded as a god in disguise Jukka O. Miettinen

Some of the puppets are revered as sacred objects, and they can even belong to the sacred court heirlooms called pusaka. One of the most sacred puppets of a wayang kulit set is, surprisingly, not a noble hero but Semar, the head of the servant clowns or punakawan of the ethically good party.

- Semar (right) and his sons Petruk, Gareng, and Baging, the punakawan or servant clowns of wayang kulit Jukka O. Miettinen

Semar is old, fat, short-legged, and flat-nosed. He is far from noble or handsome, but his eyes are those of a wise and kind person. With his soft breasts and round bottom, he is regarded as a hermaphrodite, the “father and mother” of his servant sons, the long-nosed Petruk, the limping Gareng, and the shy Bagong. The servant clowns assist the noblest heroes, and they are permitted to utter the most daring jokes.

The mood of a performance usually becomes intensified when they appear on the screen. Semar is basically seen as a god in the guise of a clown, who helps the hero achieve his goal with kindness and humour. The origin of the punakawan has led to much speculation. It is maintained that they are old indigenous deities, which have been adapted to later Indianised mythology.

This suggestion is supported by, for example, the stylisation of the Semar character, which differs drastically from the other puppets. On the other hand, clowns play a central part in numerous forms of theatre in Asia. This is also the case in Indian drama, where the sudraka, a noble-born but lazy Brahman, acts as the king’s adviser.

Gunungan

- The servant clowns have a crucial role as the assistants of the heroes. Here is one of the between two gunungan or three-of-life Jukka O. Miettinen

The wayang kulit puppets are opaque, and on the screen they are seen as dark shadows articulated by precise lace-like perforations. The screen is divided into two, the right-hand side being reserved for the good characters, and the left for the evil party. This polarity, however, is not rigid, since both parties include characters with qualities that could belong to the opposing one. At the sides of the 4-metre-long screen the puppets stand in rows with their rods stuck into the soft trunk of a banana tree placed below the screen.

When the play begins, the gunungan, a tapering structure resembling a temple spire or a tree, is removed from in front of the screen. The gunungan is the symbol of the “wayang world” and is a kind of “curtain” marking the beginning of the play, changes of scene, and the end. It is also used for special effects such as storms, or even the disruption of the cosmic order. Like all other features of wayang kulit, the gunungan has many symbolic meanings; it is said to symbolise, for example, the World Mountain, the tree of life, and the cosmic order.

Watching Wayang Kulit

In earlier times it was customary for men to watch the play from in front of the screen, while women sat behind it, thus being able to see the orchestra, the dalang, and the brightly coloured puppets. This custom is no longer maintained, at least in large-scale public performances, and today the performance can be freely viewed from both sides of the screen.

In its many variants, wayang kulit is performed throughout Java on feast days. Performances are regularly staged by the kraton, and they are also broadcast frequently. Shadow theatre still partly has its traditional, deep, and even sacral meaning, and performing and viewing the play can be experienced as a kind of spiritual exercise. However, many also claim that it has recently been too heavily popularised and is thus becoming only a form of entertainment.

Forms of Wayang Kulit

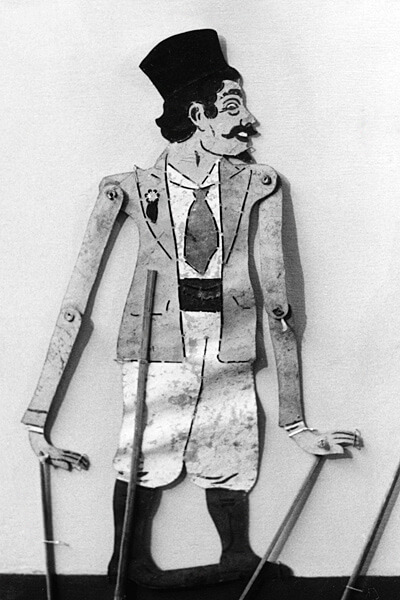

- Christian missionaries spread their doctrine by employing wayang kulit of their own style Jukka O. Miettinen

- Wayang pancasila was created during the early period of Indonesia’s independence and its puppets show political figures of the period Jukka O. Miettinen

- The Chinese community created their own version of shadow theatre, wayang kulit cina, which illustrated Chinese stories Jukka O. Miettinen

- A scene from a wayang beber storyteller’s scroll Jukka O. Miettinen

The steady popularity of wayang kulit has also made it a platform of various later ideologies. It was used to propagate the Islamic faith, and Western missionaries have also spread the message of Christianity with their Western-influenced puppets. In the mid-1950s the naturalistic puppets of wayang pancasila (Pancasila: the doctrine of the spiritual foundations of the Indonesian Republic) presented the history of Indonesian independence to the people.

The Chinese minority of Java has also developed its own shadow puppets, combining Javanese and Chinese features. There are also many wayang kulit-related drama forms, of which the most archaic is wayang beber, now practically extinct. In wayang beber the dalang illustrated the story by opening a painted scroll supported by two poles. Another now rare form is wayang klitik, based on the Islamic Damar Wulan story cycle. It was performed without a screen with flat, wooden puppets carved in relief.

Wayang Golek

Video clip: Wayang golek rod puppets manipulated by Asep Sunandar Sunaryo, a famous puppeteer from West Java Reijo Lainela

Wayang golek is a still popular form of rod puppetry, which, according to tradition, was invented by a Javanese Muslim ruler in the late sixteenth century. Its main repertoire is derived from the Menak cycle, dealing with the Muslim hero Amir Hamzah. Local variants of wayang golek have evolved in various parts of Java. The tradition is strongest in West Java, where it has been used in performing the stock repertoire of wayang purwa, that is, the Ramayana, the Mababbarata, as well as local tales, and the East Javanese Adventures of Prince Panji.

Wayang golek uses a set of 60–70 puppets, which do not always portray specific characters, but stock types, the puppets thus being interchangeable. The heads and arms are carved three-dimensionally in wood, and the lower part of the body is covered by a batik sarong, beneath which the dalang operates the rod that makes the puppet’s head turn. He uses his other hand to manipulate the rods for the arms and hands. There is no screen, the dalang, the orchestra, and the singers all being visible to the audience.

- Wayang golek puppeteer operating the rod-puppets in front of the audience Jukka O. Miettinen

Although wayang golek is performed in many places, wayang kulit is still the most popular form of Javanese puppet theatre. It is the origin of the whole “wayang family”, and has provided the general aesthetics, characterisation, and repertoire of Javanese classical theatre as a whole. The rich wayang tradition was officially added to UNESCO list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008.