Wayang Wong, The Court Dance-Drama

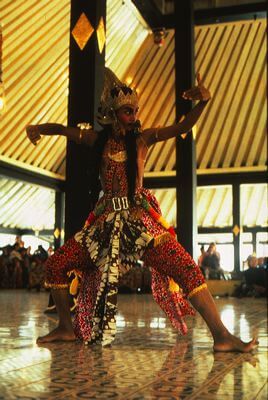

- A scene from the Ramayana performed in a traditional open pendopo hall in Yogyakarta Jukka O. Miettinen

In its grandeur and extreme stylisation, the Javanese wayang wong (wayang: shadow or puppet; wong: man) is undoubtedly one of the world’s greatest theatrical traditions. Several forms of large-scale dance-drama are known from the early periods of Javanese history. A literary source from AD 930 refers to the wayang wwang dance- drama, a kind of wayang kulit performance where the puppets were replaced by human dancers. Its dance style is assumed to have been strongly influenced by India, and the actors were masked or unmasked according to the character portrayed.

The Origins

In the East Javanese Majapahit kingdom, the court dance-drama was called raket. The stories were derived from a contemporary East Javanese story cycle known as The Adventures of Prince Panji, and the performances are known to have lasted from evening until noon the next day. The theatrical tradition of Hindu-Buddhist East Java disappeared or a least changed with the spread of Islam to Java in the fifteenth century. It was, however, adopted by the Hindu courts of Bali, where it evolved into the gambuh, the quintessentially classical style of Balinese dance-drama.

In Java, the wayang topeng mask theatre discussed above remained the most popular form of dance-drama until the eighteenth century. When the kingdom of Mataram in Central Java split in two in 1755 as a result of Dutch domination, the courts of Yogyakarta and Surakarta became rivals, mainly in the field of arts, as the Dutch had considerably curbed the actual political power of the rulers. The court of Surakarta inherited the highly valued bedhaya dance and the topeng mask theatre from the Mataram kingdom.

The Sultan of Yogyakarta, Hamengkubuwana I (1755–92), therefore began to design a new form of theatre as his pusaka heirloom. In creating the spectacular wayang wong dance-drama, he explicitly strove to revive the dance-drama tradition of the ancient Majapahit dynasty in order to emphasise his role as its true descendant.

Human Puppets

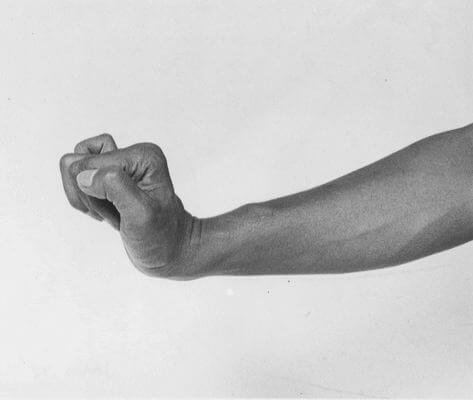

- A strong male character of wayang wong; the dance movements imitate those of wayang kulit puppets Jukka O. Miettinen

Wayang wong has many features in common with the wayang kulit shadow theatre. These include a similar overall aesthetic and the same narrative material, often from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana; even the movements of the actors clearly imitate puppets. The steps and gestures of the actors are basically “two-dimensional”, designed to move to the left and the right like the movements of puppets on the screen. Like wayang kulit, wayang wong is also accompanied by a large-scale court gamelan orchestra.

A State Ceremony

- The characters of the Ramayana enter the pendopo hall in Yogyakarta Jukka O. Miettinen

Wayang wong has been closely linked to court ceremonies. Large spectacles were staged, for example, in honour of the sultan’s coronation, or for weddings and birthdays. The performances had a deep symbolic meaning, and the hour of the spectacle and its plots were determined by the fact that the Sultan of Yogyakarta was identified with the Hindu god Vishnu.

- A battle between Hanuman and a demon Jukka O. Miettinen

- Rama instructing Hanuman Jukka O. Miettinen

- Princess Sita must prove her chastity on a pyre Jukka O. Miettinen

- After the performance the dancers kneel down and show their respect to the stage Jukka O. Miettinen

The performance began early in the morning, when the sun, identified with Vishnu, appeared in the sky. The sultan sat on a holy throne, always facing east in the middle of the famous Golden Hall under the highest point of its pyramidical roof, symbolising the axis of the universe. The performance took place on a lower level in a smaller hall annexed to the magnificent Golden Hall, for no one was permitted to stand higher than the divine sultan.

The performances, which could last several days, were grandiose events, and the audience included not only members of the court but invited colonial representatives as well. Wayang wong was an exceptionally expensive art form placing heavy demands on the kraton’s treasury. In some cases, the sultan even had to borrow money from the Dutch in order to be able to arrange these spectacles. The last full-scale court performance was staged in 1939.

Actors and Styles

In Yogyakarta, all the wayang wong actors were originally men, and included members of the royal family, other members of the court, and bodyguards. In Surakarta, Pangeran Adipati Mangkunegaran I, the contemporary and rival of Hamengkubuwana I, the creator of wayang wong, also began to compose wayang wong plays. This marked the beginning of the Surakartan wayang wong tradition of the Mangkunegaran kraton.

- The arm position in the Surakartan style is extremely curved Jukka O. Miettinen

The Yogyakartan and Surakartan styles differ in certain respects. In Surakarta women played female roles from the very beginning, and often noble hero characters as well. With its undulating movements, the Surakartan dance style is more subdued than the Yogyakartan style. There are also differences in costume and in the gamelan accompaniment.

A Complex Whole

The movements of the wayang wong dancer-actors are generally fluid and solemn, and recitation is extremely stylised. The main language of the performances is Old Javanese, not the modern language, and the actors recite the lines themselves, while singers sitting among the gamelan perform the more demanding vocal parts.

The performance is an intricately complex whole, where the concept of time and the structure is dictated by the gamelan’s soft and elaborate fabric of sound, further elaborated by the recitation, songs, and comments of the chorus. The dancer-actors move slowly, apparently according to their own logic, and from time to time remain frozen, reciting their lines in highly ornamental positions between their elegant dance movements. The chorus and the singers sitting together with the orchestra describe and comment on the events, while the actor-dancers recite their own lines in a stylised manner.

Physical Characterisation

Video clip: The Wayang Wong play Perigiwa and Pregiwati Veli Rosenberg

Because wayang wong borrowed the characterisation of shadow theatre, the style of dance, costumes, make-up, and vocal technique are all dictated by the stock types portrayed. The characters fall into three major categories: the female type, the refined male alus type, and the strong male gagah type.

- The movements of the noble alus characters are restrained Jukka O. Miettinen

The dancer’s physique determines his or her role type. The women must be petite and slender, and they should also have beautiful facial features. The noble male characters must also be slender and delicate, whereas the strong male type should be powerful in both body and appearance.

- The movements of the female characters are graceful and modest Jukka O. Miettinen

The slow female dance is restrained and graceful, and its movements are directed at a low level covering only a narrow space. The female dancer rarely lifts her feet from the floor, and the basic position is always an open demi plié bent slightly forward. The movements of the refined male type are also directed at a rather low level, but the dancers are allowed to lift their feet slightly. Their whole dance technique aims at creating an overall impression of withheld strength, so typical of the Southeast Asian ideal of a hero.

- The movements of a gagah or strong male characters are open and powerful Jukka O. Miettinen

The strong male type, on the other hand, moves energetically, standing in a very open leg position and lifting his arms and legs horizontally to create the impression of aggressive macho masculinity. All the role types use four basic hand gestures, derived from the shadow puppets. These, in turn, are partly based on the Indian-influenced dance of the Central Javanese period, as shown by preserved reliefs and sculptures. Unlike the Indian mudra, the wayang wong hand gestures do not have, at least not any more, any direct symbolic meaning. They are rather unforced, albeit extremely decorative, gestural extensions of the dance movements.

- Hand movements of Javanese dance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hand movements of Javanese dance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hand movements of Javanese dance Jukka O. Miettinen

- Hand movements of Javanese dance Jukka O. Miettinen

The above three major role types are each divided into a number of subtypes (humble, refined, proud, servant, adviser, etc.). There are a total of twenty-one role types, each with its own style of make-up and dress. The leading types have their characteristic movement patterns revealing their psychological qualities. For example, symmetrical movements indicate strength, stability, and, above all, humility, whereas asymmetry is a sign of proud and powerful energy.

Costuming, Masks and Makeup

The costume includes a brownish-black batik sarong with a tight black velvet bodice for women, while the men dance with bare torsos. Also worn are jewellery and a crown or tiara, skilfully cut in gilt leather, with the model of the headdress revealing the rank of the character. The overall aesthetics are familiar to wayang kulit, and in this century the dance costume and head-dress were made to correspond more closely to those of shadow puppets.

Characterisation is further emphasised by means of facial make-up, as masks are worn only by the demon and monkey figures. The slightly stylised make-up is light for the noble male and female roles, and red for the strong and coarse types. The facial make-up of the punakawan or servant clowns is usually white.

Make-up can be divided into seven basic types, including, for example, various models of painted whiskers and beards for the men. The actors paint their whole body with yellowish boreh liquid, giving the skin a soft golden glow.

Stories

The traditional wayang wong plots or lakons, which in the early nineteenth century finally developed into written “librettos”, are mostly based on the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. In Java, these originally Indian epics are regarded as national literature, even to the extent that their heroes are felt to be the mythical ancestors of the Javanese.

It is no wonder then that the heroes have, in a way, begun to live their own lives and have given rise to new and purely Javanese stories, which no longer have much to do with the original epic context. For example, the Lakon Rama Nitis (The Incarnation of Rama) portrays an incarnation of Prince Rama of the Ramayana as the god Krishna of the Mahabharata.

- Shiva instructing Arjuna in a modern Surakarta-style wayang wong production of Arjuna Vivaha Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arjuna rejecting the heavenly nymphs in the Arjuna Vivaha Jukka O. Miettinen

- Arrival of the aggressive Kaurava brothers in Pregiwa and Pregiwati, which is another story derived from the Mahabharata Jukka O. Miettinen

- The sisters Pregiwa and Pregiwati finally meet their noble brother Jukka O. Miettinen

One of the earliest fantasies of this kind is the kakawin court poem, Arjuna Vivaha, composed in honour of King Airlangga’s wedding in 1035, whose principal hero is the virtuous Arjuna of the Mahabharata. Although it was originally official court poetry lauding the virtues of a ruler celebrating his marriage, it has survived as one of the most beloved and valued lakon of wayang wong.

Later Developments

The flourishing period of dance and theatre, which began in the kraton of Yogyakarta and Surakarta in the mid-eighteenth century, continued throughout the following century. It led to new forms of wayang wong-related dance-drama. The best known of these are langen driya and langen mandra wanara.

Around the middle of the nineteenth century Mangkunegoro V from the Mangkunegaran kraton in Surakarta created the langen driya, based on the adventures of the hero Darmawula, a story cycle dating back to the East Javanese Majapahit dynasty. It is performed by an all-female cast, who unlike the cast in wayang wong, sing all of their lines.

Langen mandra wanara, also a kind of wayang wong-derived “dance opera”, was created in the late nineteenth century by Prince Danuredio VII of Yogyakarta. Its plot material is based solely on the Ramayana, and its name derives from the epic’s monkey characters (wanara: monkey). The monkeys also lend a special feature to the whole performing technique: langen mandra wanara is performed in a crouching position and the movement patterns are characterised by monkey-like movements and gestures.

At present, both langen driya and langen mandra wanara are rarely performed, although the latter experienced a kind of renaissance in the 1980s when a complete performance was recorded by Radio France. The original wayang wong, on the other hand, is still performed actively, and it can be truly regarded as the classical dance-drama of Java. It has evolved into new variants in the twentieth century, which has in many ways been a period of drastic change in the performing arts.